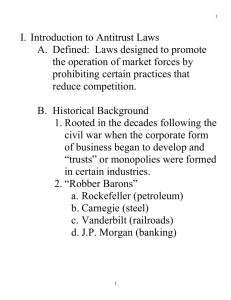

at_hammer

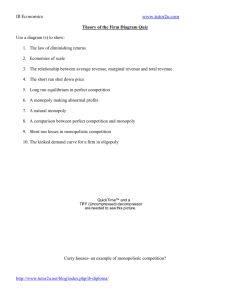

advertisement