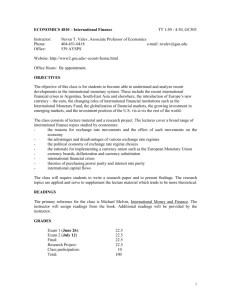

Lessons From Recent Global Financial Crises

advertisement

Contemporary Issues in Risk Management and Banking Regulation* William C. Hunter** Introduction I am pleased to have the opportunity to speak to this very impressive group of scholars and policy makers that have come together to discuss issues related to risk management and banking regulation. I will focus my remarks on the lessons that banking and financial markets regulators and policy makers have learned regarding the practice of risk management in banking and the development and implementation of risk management techniques over the past couple of decades. Let me note that much of what I have to say today derives from discussions held at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago at our annual conference devoted to international financial policy issues. The first conference, held in 1996 and cosponsored with the American Enterprise Institute, examined financial derivatives and public policy. The second, cosponsored with the World Bank, was devoted to global banking crises. The third was cosponsored with the International Monetary Fund and focused on the Asian Financial crisis. The fourth meeting was cosponsored with the Bank for International Settlements and examined the lessons learned from recent global financial crises. The fifth meeting was cosponsored with the Journal of Banking and Finance and featured academic work on quantitative risk management modeling. This year’s conference was in April and was cosponsored with the World Bank. The topic of the meeting was asset price bubbles and their regulatory, monetary, and international policy implications. The proceeding of this conference are being published by the MIT Press and the book will be available in late fall. Looking back at our experiences with risk management over the past couple of decades, policy makers have learned some important lessons that are directly applicable to how we supervise financial institutions and make monetary and regulatory policy. In particular, I believe that some of these lessons are especially relevant to regulatory reforms that are currently being advocated in the risk management and assessment areas. Risk Management and Measurement Perhaps the most basic lesson we have learned from our experience with the financial engineering and risk management activities of banking companies over the past two decades is that what is important is the underlying risk characteristics of financial instruments, not what these instruments are called. This is important because some elements of our legal and regulatory framework are undoubtedly outdated and may have unexpected consequences for such things as legal and regulatory compliance risks. For example, in the U.S. an instrument's name (totally divorced from its underlying risk characteristics) may actually determine which regulatory agency has oversight jurisdiction for that instrument and how that instrument is regulated. However, it is * Paper presented on 2002 Forum on Risk Management and Banking Regulation, July 4, 2002, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. ** Senior Vice President and Director of Research, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, USA. exactly these risks, legal and regulatory compliance, along with market risk, credit risk, operational risk, and reputational risk, to name a few, that are important to prudential supervisors. As is often noted, the use of financial derivatives does not typically involve the creation or introduction of new types of risk. However, some financial derivatives do combine or separate out different types of risk in new ways that require users to develop more advanced risk-management capabilities. And as several dealers in the over-the-counter derivatives market have learned in recent years, the marketing of new, complex financial instruments may entail special reputational risks that demand special attention. A second fundamental lesson learned with respect to the management and measurement of risks over the past two decades is that risk must be measured and managed on a portfolio basis rather than on an instrument-by-instrument or asset-by-asset basis. Clearly, the consolidated firm has the incentive to manage its risk on an aggregate basis whenever there are non-negligible diversification benefits deriving from its different units/assets/or instruments. Although this is arguably the first principle of modern finance theory and is widely practiced by financial market participants, putting this principle into practice in prudential regulation has not been so easy. For example, past banking crises have in part reflected a failure to recognize or to prudently limit concentrations of risk within portfolios (most often in real estate). In recent years, financial institutions and their supervisors have placed increased emphasis on the importance of consolidated risk management. Sometimes called integrated risk management, consolidated risk management refers to a coordinated process for managing risk on a firm-wide basis. Interest in consolidated risk management has arisen for a variety of reasons including: advances in information technology and financial engineering, the increase in the number domestic and cross-border banking mergers, and the increase in mergers between banks and non-bank financial institutions. These developments have resulted in significant consolidation in the financial services industry as well as in large, more complex financial institutions. These developments have also made the process of risk management and risk measurement more interdependent. In simple terms, consolidated risk management refers to the overall process that a firm (financial institution) follows to define a business strategy to identify the risks to which it is exposed, to quantify those risks and to understand and control the nature of the risks it faces. Thus, risk management comprises a series of business decisions, accompanied by a set of checks and balances-- risk limits, independent risk management functions, risk reporting and review, and oversight by senior management and the board of directors. Thus, consolidated risk management involves the broad process of business decision-making and of support to management in order to make informed decisions about the extent of risk taken both by individual business lines and by the firm as a whole. As is clear from this description, risk measurement-- which entails the quantification of risk exposures-- is a key (but not the only) component of a consolidated risk management system. This quantification may take a variety of forms-value-at-risk (VaR), earnings-at-risk (EaR), stress scenario analyses, duration gaps, etc. depending on the type of risk being measured and the degree of sophistication of the estimates. 2 The movement towards consolidated risk management means that the risk measures that underpin the overall risk management process must better reflect the fact that risk is managed on a portfolio or consolidated basis rather than on an instrument by instrument basis, and they must also be capable of capturing or quantifying the extreme/nonnormal risk events that are likely to be associated with large complex financial institutions and the spillover effects that accompany financial crises and severe market disruptions in a more integrated global financial system. This is the third fundamental lesson learned. To adequately deal with the portfolio approach to risk management, the notion (or criterion) of a coherent risk measure has been put forth (Artzner, et al. 1997, "Thinking Coherently," Risk, Vol. 10, No. 11, pp. 69-71). Essentially, a risk measurement methodology will yield a coherent risk measure if the capital required to protect a portfolio of two positions is no greater than the sum of the capitals required for each position. That is, if the risk measure satisfies a sub-additivity property. Hence, coherent risk measures capture the diversification effects associated with portfolios of less than perfectly positively correlated assets or risks. With respect to the level of capital required for bank credit risks, the recent Basle capital proposals it did not go as far as to authorize the application of sophisticated portfolio credit risks models by individual banks. However, the proposal clearly raises the bar for the level of sophistication of credit risks models and has motivated the development and enhancement of internal credit rating systems and other credit risk capital considerations including operations risk, and their impact on economic capital and the pricing of credit assets. Given that many of the traditional methodologies for quantifying credit and portfolio risks such as VaR are not coherent (e.g., there are cases where a portfolio can be split into two sub-portfolios such that the sum of the VaR corresponding to the subportfolios is smaller that the VaR of the total portfolio), more robust risk measures are required. In addition, more research aimed at the related problem of developing coherent risk measures that perform well in the face of extreme movements of the types associated with financial crises and severe market disruptions would be welcomed. Although risk measurement methodologies are still evolving and have some significant limitations, they do facilitate the identification and quantification of concentrations of risk within trading and asset portfolios. This is accomplished by analyzing derivatives and other financial instruments and assets in terms of their effect on the sensitivity of the institution's total portfolio to changes in a common set of underlying market risk factors- interest rates, exchange rates, commodity prices, and equity index values, among others. Clearly, the usefulness of these measures is highly dependent on the degree that correlations among the common risk actors are accurately measured. In recent years, leading commercial and investment banks have devoted increased attention to measuring credit risk and have made important gains, both by employing innovative and sophisticated risk modeling techniques and also by strengthening their more traditional practices. For example, some market vendors model measures of default risk by applying option theory to the market value of a borrower's equity share price and calculates the probability of a negative net worth. This approach has the 3 important feature of incorporating market assessments of risk into the analysis and is often used to validate a bank's independent view. Other models, including many used at commercial banks, take a more direct approach to calculating the fundamental elements of credit risk. They estimate the probability a borrower will default, based on numerous measures of financial strength; the bank's exposure given a default, reflecting any unused commitments of the bank to lend; and the expected loss given default, taking into account any collateral or other lossmitigating features of the credit agreement. Combined, these measures reveal the expected loss, which a bank must know to underwrite and price a credit correctly, as well as to establish adequate loss reserves. However, it is the volatility of this loss and the contribution of the credit to the volatility of the bank's cash flow on a firm-wide, portfolio basis that is crucial to evaluating capital adequacy. Thus, testing the sensitivity of these models’ results to perturbations in the key factors that underpin their construction is a key ingredient required to ensure the integrity of the consolidated risk management decisions that flow from these models. Another lesson that our experience with risk management over the past two decades has driven home is the critical importance of firms' internal risk controls. This, of course, is a key component of an effective consolidated risk management program. As noted above, given proper quantification of risks, a comprehensive set of risk limits carefully monitored and strictly enforced, is a prerequisite for realizing the full benefits of new financial engineering technologies and instruments while avoiding the obvious pitfalls. Related to the need for effective monitoring and enforcement of risk limits is the need to align financial incentives with management objectives. Stated differently, an effective consolidated risk management system requires that compensation schemes in financial firms reflect not only the returns generated by traders and portfolio managers but also the risk assumed in generating the returns. Again, this requires that the firm accurately quantify its risks. In this regard, many leading commercial and investment banks are well aware of the need to link the compensation of individuals who are empowered to commit the firm's resources to the risks actually undertaken. The Importance of Financial Infrastructure The Asian financial crisis of 1997 and the subsequent crises in Russia and Brazil in 1998 taught us much about the relationship between risk management and macroeconomic and global financial stability. In the fall of 1998, after Russia’s debt default and devaluation and the near collapse of the hedge fund Long Term Capital Management, international financial markets seized-up for nearly all high-risk borrowers including those in the United States and other developed economies. At that time, the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee lower its intended or target federal funds rate three times (by a cumulative total of 75 basis points) in response to the systemic threat posed by these developments. Global growth slowed dramatically but systemic crisis was averted. Two things seem clear with hindsight. First, credible signaling by a central bank of its intent to contain an incipient financial crisis can solve problems associated with coordination failure in financial markets. Second, the long period of remarkable economic growth and prosperity in Asia masked 4 weaknesses in risk management at many financial institutions. Many Asian banks did not assess risk or conduct cash-flow analyses before extending loans. Instead, they lent on the basis of their relationships with the borrowers and the availability of collateral-despite the fact that collateral was often hard to seize in the event of default (due to poorly specified and/or unenforceable bankruptcy laws). The result was that loans-including loans by foreign banks--expanded faster than the ability of the borrowers to repay. In addition, because many banks did not have or did not abide by limits on concentrations of lending to individual firms or business sectors, loans to overextended borrowers were often large relative to bank capital, so that when economic conditions worsened, these banks were weakened the most. The Asian crisis also illustrates the potential benefit of more sophisticated risk management practices. Many Asian banks did not adequately assess their exposures to exchange rate risk. Although some banks matched their foreign-currency liabilities with foreign-currency assets, doing so merely transformed exchange-rate risk into credit risk, because their foreign-currency borrowers did not have assured sources of foreigncurrency revenues. Similarly, foreign banks underestimated country risk in Asia. In both cases, institutions seemed to have assumed that stability would continue in the region and failed to consider what might happen if that were not the case. A greater willingness and ability of banks to subject their exposures to stress testing could have highlighted the risks and emphasized the importance of key assumptions. Had they conducted stress tests, some lenders might have seen how exposed they were to changes in exchange rates or to an interruption of steady economic growth. Regarding the lessons to be taken from recent experiences with financial crises around the world, (Asia and Russia being among the most recent), first, no one country should be consider itself immune to financial crisis and second, the cost of resolving a crisis once it has occurred is almost certain to be very high. For example, over the past 20 years alone, more than 125 countries, including the United States, have experienced at least one serious financial or banking crisis. In more than half of these episodes, a developing country’s entire banking system became insolvent. In more than 40 cases the cost of resolving the crises averaged about 12.8 percent of GDP. In developing countries (over all) the percentage was even higher at about 14.3 percent. The details of the more recent crises are probably familiar to everyone here today, so I will not describe them in detail. Just let me say that, similar to the Asian countries, countries suffering financial crises over the past three decades typically exhibited many of the same characteristics: government directed and connected lending, poor supervision of the financial system, inadequate legal infrastructure, absence of a credit culture in which lenders and investors make judgements based on independent credit assessments and sound financial analysis, underdeveloped bond and long term capital markets, lack of adequate accounting disclosure and transparency, ineffective systems of corporate governance, and 5 excessive and imprudent risk-taking by financial institutions operating with explicit or implicit deposit insurance schemes or governmental guarantees, among others. However, at the same time these same countries also had unique elements that contributed and in many cases, set off their particular episodes: weak fixed exchanges rate regimes (often pegged to the U.S. dollar), significant debt and asset price deflation, and in some cases persistent current account deficits, most often financed by short-term unstable foreign capital inflows, among others. Thus, another lesson we have learned from recent global financial crises is that while most crises have much in common, they nevertheless can have unique precipitating elements. The list of common characteristics observed in the crisis countries suggests lessons in and of themselves. Stated differently, another (and perhaps the most important) lesson we have learned regarding the potential for economy-wide financial crises, is that infrastructure, broadly defined to include most of these common characteristics, matters. Countries with strong financial infrastructures including good operational (and not just theoretical) systems of supervision and regulation, legal frameworks, and private property rights (including bankruptcy laws) have tended to be more immune to financial shocks and have tended to enjoy more stable rates of growth. Such stability in the financial system breeds the necessary trust that the Federal Reserve considers essential to a well functioning competitive financial system. Recent research has shown that weakness of legal institutions for corporate governance had an important effect on the extent of currency depreciations and stock market declines in the Asia crisis countries. Measures of legal protections, enforceability of contracts, corruption, and judiciary efficiency were all shown to be important in determining the depth of the crisis. Thus, it is clear that an effective financial infrastructure, defined broadly as above, is a prerequisite for promoting market discipline. Based on my remarks to this point, it seems clear that an economy susceptible to financial crisis due to weak infrastructure is analogous to a human body with a weakened immune system. An immune system with strong fundamentals can shrug off minor infections without harm. However, the same low-grade concerns can wreck havoc on a weakened immune system leading to systemic crisis. In this case, as with financial crises, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Since we can not fully protect against or eliminate every potential risk factor that might give rise to a crisis (financial or medical), devoting proper attention to preventive actions seems very appropriate. This includes coordinated actions to improve the global financial infrastructure or architecture (examples include efforts like the BIS capital standards and the core banking principles). Although there seems to be a consensus regarding the value of a strong financial infrastructure, there is less of a consensus regarding the optimal design of this infrastructure, including among other things, the exact role to be played by the multilateral agencies in the grand design. Continuing with my medical analogy: 6 What is the role of the doctor? (the regulator?) What medicines should be prescribed? (what intervention or regulation is required?) What is the correct dosage? (how extensive should the regulation be?) How long should the patient continue on the medication? (when should the regulation be repealed?) How will the patient be monitored? and When is the patient cured? For some illnesses, the answers to these questions are well known. For other, more exotic diseases, more research is obviously required. Similarly, in the case of financial crises, more research is needed on issues related to the optimal design and implementation of a financial architecture. Coordinated Supervision and Market Discipline Banking supervisors have learned the importance of ensuring that incentives induced by capital regulations are compatible with supervisory objectives. In this regard, efforts to enhance public disclosures of the scale and scope, results, and risks of bank trading activities have been motivated by a desire to bring greater market discipline to bear on banks. In addition, supervisors have begun to attempt to build better financial incentives into regulatory capital requirements. The recent proposed amendments to the Basle Capital Accord are designed to provide incentives for accurate risk measurement by allowing banks to select that approach which best reflects underlying risks and associated capital levels. As the complexity of institutions, instruments, and markets—highlighted by increased interconnectedness driven by advances in technology (both, information processing technology and financial technology or financial engineering) increases, the probability of market surprises and the need for coordinated supervision and regulation will almost surely increase. In this regard, another lesson we have learned is that direct measures of risk-taking can provide misleading assessments of overall exposure in an environment characterized by complex interconnections among policies, institutions, instruments, and markets. These interactions almost always produce non-normally distributed outcomes (the “so called fat tails” problem) or surprise correlations in situations where outcomes were thought to be ex ante independent. For example, direct lending exposure of global depository financial institutions to Thailand, Malaysia, and South Korea were limited at the time of the crisis. However, proxy hedging of these risks in other more liquid and deep markets—including those in Hong Kong, Australia, Brazil, and Mexico proved costly when these markets were adversely impacted by the evolving events and their spillover effects. The possibility of the need for increased regulatory and supervisory coordination has been taken by some as grounds for supporting the case for a single global financial regulator. It is my belief that this growing desire for centralized regulation must be tempered with caution, given the inherent difficulties associated with the design and implementation of socially optimal regulation. As is well known, inappropriate 7 implementation of even well designed regulation tends to create more problems than it solves. This is because regulation does not occur in a vacuum…firms and agents react to changes in regulation in ways to affect the effectiveness of the regulation. In essence, regulators must know exactly how economic agents will react in order to implement optimal regulatory rules. However, given that regulators are generally looking from the outside in, such understanding is difficult and elusive. This is why enhancing market discipline is so important to the overall process of international harmonization of regulation. Market discipline compliments regulators’ efforts allowing for more effective supervision. To be sure, regulators have learned that there is no way to ensure a fail-safe financial system. Regulators need help and market discipline provides a partial solution. Enhancing market discipline through dynamic incentive compatible approaches is the next challenge confronting the Federal Reserve System and regulators more generally. From the perspective of the Federal Reserve, we must respond to the recently passed financial modernization legislation (the Gram Leach Bliley Act) which allows full affiliation of banking and securities and insurance activities creating large complex banking organizations which have to be effectively supervised and regulated. Clearly, that regulation must be adaptive. Similarly, in the case of emerging markets and transitioning economies, regulation must be dynamic and adaptive. This makes sense since these markets/economies are in fact emerging and/or in transition. The Chicago Fed has long pushed for more market discipline through increased disclosure and transparency and through such schemes as mandatory issuance of subordinated debt by large complex banking organizations. In our view, mandatory subordinated debt is incentive compatible in that it aligns the incentives and risk preferences of bondholders with those of bank supervisors. Being subordinated to other liabilities, the debt holders would be risk sensitive and would monitor and discipline bank behavior. They would demand higher rates from riskier banks (a direct effect) and have stronger incentives to quickly resolve problems and avoid forbearance and its associated costs. In addition, increases in interest rate spreads provide signals to supervisors that risk is increasing (an indirect effect). A recent issue of the Chicago Fed’s journal—Economic Perspectives (Spring 2000) contains a comprehensive article on subordinated debt and its advantages as a tool for regulators in supervising large complex banking organizations. Derivatives and Monetary Policy Before closing, let me share a few observations regarding derivatives, financial crises, and the conduct of monetary policy. Regarding financial derivatives and their role in contributing to financial crises and systemic risk, it turns out that all the talk about financial wizardry that allows unbundling and transferring of risks and the lightening speeds of transmission of these risks across markets was probably overblown. That is, recent crises remind us that by and large, the mistakes of the past few years were rather ho-hum or ordinary and not so exotic—making bad loans (typically in real estate), failure to evaluate counterparty credit risk, or simply relying on the lofty reputations of firm principals (a la Long Term Capital Management). These are age-old problems (especially in the banking industry). The lesson here is that derivatives were not a 8 major villain in recent crises. This suggests that maybe the first lesson we should learn is not to forget the old lessons! With regards to matters monetary policy, there is much disagreement on the overall effectiveness of monetary policy in a world of sophisticated financial derivatives. It could be that derivatives, in addition to complicating monetary policy, might also reduce the impact monetary policy has on the real economy. That is, a given amount of monetary stimulus may have a smaller effect. For example, the existence of foreign exchange derivatives may reduce the ability of central banks to influence exchange rates. Since money should be neutral in a frictionless economy, the sources of monetary nonneutrality must lie in economic frictions such as informational imperfections and transactions costs. By increasing the liquidity, depth, flexibility and transactional efficiency of financial markets, derivatives increase the speed with which monetary policy actions are transmitted throughout the financial system. Lower transaction costs and reduced frictions resulting from derivatives activities increase the rate at which new information, including policy actions, is impounded into market prices. Since derivatives markets reduce these sorts of frictions, they provide a more efficient mechanism for price discovery, speed up information transmission, and reduce informational asymmetries. Thus, it follows that by reducing frictions, derivative markets may actually reduce the real effects of monetary policy actions. Furthermore, derivative markets act as a mechanism for spreading shocks across the economy as a whole. To the extent that derivatives reduce the force of monetary policy, monetary policy may become a weaker tool for counter cyclical stabilization policy. However, if derivatives do provide the economy with the benefits cited by their proponents, that is, a more efficient, self-correcting and shock resistant economy, then there should be less of a need for counter cyclical monetary policy. Stated differently, derivatives activity might actually reduce the incidence and severity of business cycles themselves. Conclusion Before closing, we highlight another important lesson learned from recent experiences with financial crises and risk management. This lesson is that modern finance (as a discipline) can be very useful in the design of economic institutions and policies as modern macroeconomics is. Understanding such financial concepts as market microstructure and option value can be just as important in forecasting and mitigating crises as is a sound understanding of modern macroeconomics. The Asian crisis is a good example of this given that most of the countries had good macroeconomic fundamentals but significant imbalances on the finance-side which escaped the scrutiny of economists and policy makers. Indeed, such notions as agency costs, moral hazard, signaling, complete and incomplete markets, bankruptcy and strategic default, and other micro level incentive related concepts proved critical in fully understanding the recent crises. The bottom line is that finance is important and the kind of work that many of the researchers attending this conference are doing can prove valuable for the design of macroeconomic and regulatory policy. 9