Chapter 1: COLUMBUS, THE INDIANS, AND HUMAN PROGRESS

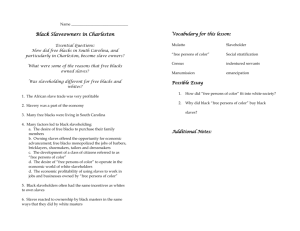

advertisement