Syllabus: Legal History Methodologies (Seminar)

advertisement

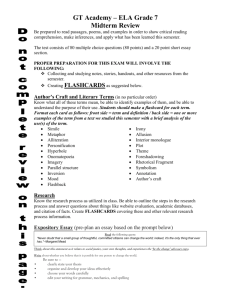

Law and Society Upper Level / Graduate Seminar Instructor: Ryan Poe Course Description What is the relationship between the law and society? This is perhaps the defining question of every new generation of legal methodology. The triumph of legal formalism in the late nineteenth century left a legacy of law's transcendence and internal consistency that the first legal historians tended to take for granted. This binary portrayal of law and society—depicting law as an entirely separate structure above or outside of society—is the foundation upon which subsequent generations of legal historians have added or removed elements, such as politics, culture, and power. Some have depicted two-way exchanges between law and society, with interest groups, cultures, economics, lawyers, and even the ontology emerging from the law itself acting as mediators and causal agents in history. Others have subverted this dualistic paradigm altogether by incorporating alternative means of rule-making into their narratives, challenging the seeming hegemony of law as a system of rule. This course is a graduate-level seminar on Law & Society, focusing on methodological uses of the law in historical writing. Each week we will read the works of scholars employing a particular type of legal history methodology in an effort to understand the trajectory of legal history and build a framework from which students can examine the relationship between law and society in their own subjects of interest. Learning Objectives By the conclusion of the course, you are expected to be able to do the following: Describe the general methodological trajectory of legal history—with an AngloAmerican focus, or wider should you choose—at least from the early-twentieth century to the present. Identify the prominent authors in each of our surveyed methodological types. Produce a paper of a negotiated length and type that converses with or uses one or more methodologies in legal history. Construct an argument in writing based on a clear thesis, supported by, yet critically engaged with, relevant evidence. 1 Evaluation This is a seminar course, meaning that attendance is required and class participation is the primary metric that I will use to evaluate you. Attendance (10%) Attendance, of course, is not required. However, you are allowed one unexcused and one excused absence per semester. Things come up in life that may preclude you from making it to class, so don't sweat it if you are unable to make it one day. If it becomes problematic, you may be confronted outside of the classroom and/or asked to produce extra written work to ensure that you are reading the subject material. However, if you miss beyond your two allowed absences, you will not get an A, barring extenuating circumstances. Discussion Questions (20%) Every week, if you are not leading, you must produce no more than 3, onesentence discussion questions, which you will email to that week's leader to help them facilitate discussion. Group leaders are responsible for reporting people who do not provide questions if it becomes a problem. Discussion Leading (30%) You will be required to lead discussion at least once in this course. We will choose which week or weeks you will lead on the first day of class. Everyone is required to lead, even if that means multiple people lead on the same day. Similarly, you may be required to lead more than once if there are not enough people to distribute discussion leadership evenly. Those who lead more than once will, of course, be awarded extra credit! Every week, I will supply the broadest, most important works on a specific methodology. Discussion leaders are then tasked with sending to the class one or two articles from scholars who use that method, either explicitly or implicitly. This will be a challenge, so do not hesitate to come to me for help should you need it. You are allowed to assign books, but only if three weeks ahead of time. If assign a book, I prefer if you select passages or chapters that best exemplify their method rather than the whole work. This allows you to scan the appropriate materials and send them to the class, as well. Please, give your fellow students ample time to read your contributions. This means try to have your articles or scanned section to us no fewer than two days before class. Final Paper (40%) At the end of the semester you will turn in one research paper, analytical essay, or historiographical essay that converses with one or more of the methodologies we discuss in class. On the first day of class, you will arrange a meeting with me to begin deciding your paper topic. We will talk about your paper and you will produce various assignments related to it several times over the course of the semester. These will help you think about the project, but the only thing you will be evaluated on is your final essay. Your essay precis are short, one-page, single-spaced descriptions of the topic 2 you are writing, or intend to write about for the final essay. You will produce two of these over the course of the semester for your and your classmates' benefit. Make sure they demonstrate some intellectual change between them. Nobody's project remains static over the course of the semester! Each student will submit to me their precis three days before class so that they can be circulated and read. A precis is a single-paged description of a work. For our purposes, that means you want to have it arranged in three paragraphs. Generally, the first paragraph is a summary of the content you will describe. The second is how you will look at that content—your method. The final paragraph (and usually the shortest) consists of how your method allows you view your content differently from those who came before you. Or, if someone has already viewed it with that method, how you contribute to the discussion. Writing precis is hard, but you will not be graded on these and they are entirely for your benefit. You will have two chances to build toward your essay through this assignment, so use it to your full advantage. Attendance Because this is a graduate-level seminar, you are required to attend class every day, barring your two permitted absences. Keep in mind, however, that if you miss beyond your two allowed absences, you will not be able to make an A in this course, barring extenuating circumstances. (This section must be altered to take into account any institutional attendance requirements.) Readings and Course Structure It goes without saying that you are expected to have fully read the material for each class session. Participation is required to demonstrate that you have read and understand the material. The goal of discussion is to spark critical engagement with both secondary and primary sources, to question every aspect of an argument, historical document, or methodology. Above all, keep in mind: do not be afraid to ask what you think is a dumb question! I plan on asking my share of dumb questions this semester. Remember: we are all here to learn. Even me! Code of Conduct (This section must be altered to take into account any institutional attendance requirements.) Required Texts This course will primarily be article driven, but there are a few texts that required to be on your bookshelf if you take legal history seriously. The ones that we will use are listed here in the order that they will be assigned. James Willard Hurst, Law and the Conditions of Freedom in the Nineteenth3 Century United States (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1956). Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005 [1973]). Morton J. Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law, 1780-1860 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977). Course Calendar Week 1 Course Introduction Week 2 Week 3 Formalism as Legal Method Charles C. Goetsch, "The Future of Legal Formalism," The American Journal of Legal History 24, no. 3 (1980): 221-256. Ernest J. Weinrib, "Legal Formalism: On the Immanent Rationality of Law," The Yale Law Journal 97, no. 6 (1988): 949-1016. Gary Lawson, The Constitution of Empire: Territorial Expansion and American Legal History Edited by Guy Seidman. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004). Functionalism: J. Willard Hurst's Consensus Week 4 Week 5 Introductions Expectations and Requirements ◦ Expectations and Requirements ◦ Leaders ◦ Final Paper ▪ Goals ▪ Expected Assignments Assign Meetings and Leaders James Willard Hurst, Law and the Conditions of Freedom in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1956). Functionalism: Conflict and Reflectionism Harry N. Scheiber, Ohio Canal Era: A Case Study of Government and the Economy, 1820-1861 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1968), foreword, introduction, conclusion (supplied). Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005), pp. Ix-xx, ch. 8. Functionalism: Evolving Law 4 George L. Priest, "The Common Law Process and the Selection of Efficient Rules," The Journal of Legal Studies 6, no. 1 (1977): 65-82. Richard A. Posner, "A Reply to Some Recent Criticisms of the Efficiency Theory of the Common Law," Hofstra Law Review 9 (1980-1981): 775-794. Gunther Teubner, "Substantive and Reflexive Elements in Modern Law," Law & Society Review 17, no. 2 (1983): 239285. Essay Precis Due Week 6 Discussion: Essay Precis Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Read each other's precis and prepare to answer and ask questions. Marxism: Orthodoxy G. A. Cohen, Karl Marx's Theory of History: A Defence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001 [1978]), ch. 8 (supplied). Andrew Vincent, "Marx and Law," Journal of Law and Society 20, no. 4 (December, 1993): 371-397. Neo-Marxism: The Lawbomination! Eugene Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Pantheon Books, 1974), pp. 25-49 (supplied). Douglas Hay, “Property, Authority, and the Criminal Law,” in Hay, Peter Linebaugh, el al., eds., Albion's Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth-Century England (New York: Pantheon, 1975), pp. 17-64 (supplied). Morton J. Horwitz Morton J. Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law, 1780-1860 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977). Essay Precis #2 Due Week 10 Discussion: Essay Precis #2 Week 11 Read each other's precis and prepare to answer and ask questions. Critical Legal Histories 5 Week 12 Week 13 Week 14 Robert W. Gordon, "Critical Legal Histories," Stanford Law Review 36, no. 1/2 (1984): 57-125. Laura F Edwards, "The History in “Critical Legal Histories”: Robert W. Gordon. 1984. Critical Legal Histories. Stanford Law Review 36:57–125," Law & Social Inquiry 37, no. 1 (2012): 187-199. Legal History from Below Hendrik Hartog, William E. Forbath and Martha Minow, "Introduction: Legal Histories from Below," Wisconsin Law Review 1985 (1985): 759-766. Hendrik Hartog, "Pigs and Positivism," Wisconsin Law Review 1985 (1985): 899-935. Martha Minow, "Forming Underneath Everything That Grows: Toward a History of Family Law," Wisconsin Law Review 1985 (1985): 819-898. Law as Text / Law as Context Gary Peller, "The Metaphysics of American Law," California Law Review 73, no. 4 (1985): 1151-1290. William W. Fisher, "Texts and Contexts: The Application to American Legal History of the Methodologies of Intellectual History," Stanford Law Review 49, no. 5 (1997): 1065-1110. Society as Law as Society Catherine Fisk and Robert Gordon, "'Law As . . .': Theory and Method in Legal History," UC Irvine Law Review 1, no. 3 (2012): 519-541. Christopher Tomlins and John Comaroff, "'Law As . . .': Theory and Practice in Legal History," UC Irvine Law Review 1, no. 3 (2012): 1039-1079. Final Essays Due 6