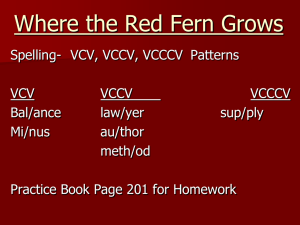

ferns - Nathaniel Whitmore

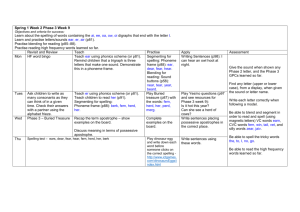

advertisement