Natural Rights – Grade 11

Ohio Standards

Connection:

Government

Benchmark B

Explain how the U.S.

Constitution has evolved

including its philosophical

foundations, amendments

and court interpretations.

Indicator 7

Explain the philosophical

foundations of the

American political system

as outlined in the

Declaration of

Independence, the U. S.

Constitution, and the

Federalist Papers with

emphasis on the basic

principles of natural rights.

Social Studies Skills and

Methods

Benchmark C

Develop a research project

that identifies the various

perspectives on an issue

and explain a resolution of

that issue.

Indicator 7

Identify appropriate tools

for communicating a

position on an issue (e.g.,

electronic resources,

newsletters, letters to the

editor, public displays and

handouts).

Lesson Summary:

This lesson uses the debate over the ratification of the U.S.

Constitution to explain the philosophical foundations of the

American political system. It focuses on natural rights, as

discussed by the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, as a key

issue in the establishment of the American government and

political system. It also asks students to identify how people

communicate a position on an issue, both during the

constitutional debates and today.

Estimated Duration: Three hours and 30 minutes to four

hours and 10 minutes

Commentary:

This lesson provides an introduction into further discussions

of citizenship rights and responsibilities and the U. S.

Constitution. It also encourages students to think about how

political opinions and positions can be communicated to the

public. One reviewer noted that this lesson provided “very

fertile ground” for meaningful conversation and writing by

students.

Pre-Assessment:

Engage students in a dialogue about rights and record their

responses on a chalk or marker board so that they will be

available for class viewing during the discussion. Ask the

following questions:

1. What are some examples of the rights enjoyed by

American citizens?

2. Are there different categories or kinds of rights?

3. Are some rights more fundamental or basic than others?

4. How are these rights guaranteed and protected in the

American political system?

Scoring Guidelines:

Determine which members of the class have grasped the basic

concepts necessary to complete the lesson. If a majority of the

students cannot name basic rights, distinguish between kinds

of rights, or cite documents like the Bill of Rights, begin

instruction with a review of these concepts.

1

Natural Rights – Grade 11

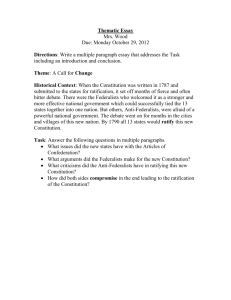

Post-Assessment:

Have the students write an essay detailing how they would make the Federalist or AntiFederalist case for ratification using present day communication tools. See Attachment C,

Making the Federalist or Anti-Federalist Case, for the essay assignment.

Scoring Guidelines:

See Attachment C, Making the Federalist or Anti-Federalist Case for the scoring rubric.

Instructional Procedures:

Day One

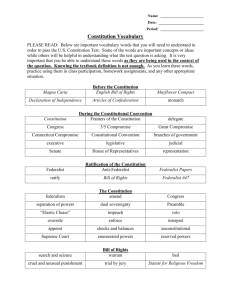

1. Based on the results of the pre-assessment, define basic terms and concepts for the class

(see Vocabulary). These terms and definitions may be written on a chalk or marker board

or provided as a handout.

2. When the class understands the basic definitions, introduce the philosophical and political

origins of natural rights. Read the opening passage of the Declaration of Independence,

and brainstorm with the class about what the authors meant by the “unalienable” right to

life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

3. Distribute and allow time for students to review Attachment A, Constitution Debate

Quotes. Any reading they do not finish in class should be done prior to Day Two. Have

students use highlighters to identify key points made by the Federalists and AntiFederalists. Have students share key points with a partner.

Day Two

4. Ask for student reaction to Attachment A, Constitution Debate Quotes. Review the

debate about ratification of the Constitution. Make sure students understand that

opponents of ratification, the Anti-Federalists, feared that the Constitution would vest too

much power in the U.S. government and provide inadequate protection for natural rights.

5. Tell students to use a graphic organizer (T-chart or web) to take notes on each side’s

arguments about the Constitution’s impact on natural rights. At the end of the discussion,

have students share what they have written in their graphic organizer to ensure that the

class has understood the major points of each position.

6. Distribute Attachment B, The Bill of Rights. Explain how the proposed adoption of a bill

of rights helped allay fears about inadequate protection of natural rights and helped to

secure ratification of the Constitution.

Day Three

7. Tell the class that the Federalists and Anti-Federalists had fewer communication tools

available to convey their positions to the public than today’s political activists. Ask the

class to list communication tools available in the 1780s and in the present, using a T-chart

to organize and record their responses. Toward the end of the discussion, have students

share the items from their T-charts with the class.

8. Using the T-charts for reference, lead a discussion on the effectiveness and

appropriateness of the tools listed for communicating a position on an issue in the present

2

Natural Rights – Grade 11

day. Are some of the methods from the 1780s still useful today? What new methods

might be more effective? List the advantages and disadvantages of each.

9. Distribute Attachment C, Making the Federalist or Anti-Federalist Case. Review

instructions with the class and assign a due date.

Differentiated Instructional Support:

Instruction is differentiated according to learner needs, to help all learners either meet the

intent of the specified indicator(s) or, if the indicator is already met, to advance beyond the

specified indicator(s).

If a number of students need help on basic concepts, distribute copies of the Declaration

of Independence for students to read and discuss in small groups. During this reading and

discussion period, work with students experiencing difficulties.

Challenge students to conduct research on the Federalists, Anti-Federalists, or other

topics, for presentation to the class.

Encourage students to read small sections of the Federalist and Anti-Federalist readings

and restate the key points in their own words.

Extensions:

Have students conduct research on current debates concerning rights enumerated in the

Bill of Rights (e.g., freedom of speech, the right to bear arms).

Assign students to examine other nations that have adopted new forms of government,

either recently or in the past. How do the nation(s) in question protect citizen rights in the

new government?

Have students compare the Bill of Rights in the Ohio Constitution with the U.S.

Constitution.

Homework Options and Home Connections:

Have students ask parents, family or friends what communication tools they have used to

articulate a position on a political issue.

Interdisciplinary Connections:

English Language Arts

Writing Conventions

Benchmark A: Use correct spelling conventions.

Indicator 1: Use correct spelling conventions.

Benchmark B: Use correct punctuation and capitalization.

Indicator 2: Use correct capitalization and punctuation.

Benchmark C: Demonstrate understanding of the grammatical conventions of the

English language.

Indicator 3: Use correct grammar (e.g., verb tenses, parallel structure, indefinite and

relative pronouns).

3

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Materials and Resources:

The inclusion of a specific resource in any lesson formulated by the Ohio Department of

Education should not be interpreted as an endorsement of that particular resource, or any of

its contents, by the Ohio Department of Education. The Ohio Department of Education does

not endorse any particular resource. The Web addresses listed are for a given site’s main

page, therefore, it may be necessary to search within that site to find the specific information

required for a given lesson. Please note that information published on the Internet changes

over time, therefore the links provided may no longer contain the specific information related

to a given lesson. Teachers are advised to preview all sites before using them with students.

For the teacher: Chalk or marker board.

For the students: History or government textbooks for reference, highlighters, writing

materials.

Vocabulary:

Federalist

Anti-Federalist

limited government

natural rights

Enlightenment

Federalist Papers

Bill of Rights

consent of the governed

republic

communication tools

faction

unalienable rights

Technology Connections:

Use the Internet to access Web sites that contain many of the necessary documents, as

well as background material. Visit http://www.yale.edu at Yale University Law School

and search for the Avalon Project. This site includes the Federalist Papers.

Visit http://www.utulsa.edu, University of Tulsa’s Web site which provides full text

versions of the Anti-Federalist Papers. Use the site’s search engine to search for AntiFederalist.

Research Connections:

Marzano, R. et al. Classroom Instruction that Works: Research-Based Strategies for

Increasing Student Achievement, Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and

Curriculum Development, 2001.

Identifying similarities and differences enhances students’ understanding of and

4

Natural Rights – Grade 11

ability to use knowledge. This process includes comparing, classifying, creating

metaphors and creating analogies and may involve the following:

Presenting students with explicit guidance in identifying similarities and

differences;

Asking students to independently identify similarities and differences;

Representing similarities and differences in graphic or symbolic form.

Summarizing and note-taking are two of the most powerful skills to help students

identify and understand the most important aspects of what they are learning.

Nonlinguistic representations help students think about and

recall knowledge. This includes the following:

Creating graphic representations;

Generating mental pictures.

General Tips:

If a majority of the class is unfamiliar with the Constitution or the history of ratification,

review material contained in earlier indicators.

This lesson could be integrated into a history unit on the Revolutionary and

Constitutional eras.

Attachments:

Attachment A, Constitution Debate Quotes

Attachment B, The Bill of Rights

Attachment C, Making the Federalist or Anti-Federalist Case

5

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment A

Constitution Debate Quotes

Federalist #1: Alexander Hamilton

. . . And yet, however just these sentiments will be allowed to be, we have already sufficient

indications that it will happen in this as in all former cases of great national discussion. A

torrent of angry and malignant passions will be let loose. To judge from the conduct of the

opposite parties, we shall be led to conclude that they will mutually hope to evince the

justness of their opinions, and to increase the number of their converts by the loudness of

their declamations and the bitterness of their invectives. An enlightened zeal for the energy

and efficiency of government will be stigmatized as the offspring of a temper fond of despotic

power and hostile to the principles of liberty. An over-scrupulous jealousy of danger to the

rights of the people, which is more commonly the fault of the head than of the heart, will be

represented as mere pretense and artifice, the stale bait for popularity at the expense of the

public good. It will be forgotten, on the one hand, that jealousy is the usual concomitant of

love, and that the noble enthusiasm of liberty is apt to be infected with a spirit of narrow and

illiberal distrust. On the other hand, it will be equally forgotten that the vigor of government

is essential to the security of liberty; that, in the contemplation of a sound and well-informed

judgment, their interest can never be separated; and that a dangerous ambition more often

lurks behind the specious mask of zeal for the rights of the people than under the forbidden

appearance of zeal for the firmness and efficiency of government. History will teach us that

the former has been found a much more certain road to the introduction of despotism than

the latter, and that of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics, the greatest

number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing

demagogues, and ending tyrant. . . .

Federalist #2: John Jay

. . . Nothing is more certain than the indispensable necessity of government, and it is equally

undeniable, that whenever and however it is instituted, the people must cede to it some of

their natural rights in order to vest it with requisite powers. It is well worthy of consideration

therefore, whether it would conduce more to the interest of the people of America that they

should, to all general purposes, be one nation, under one federal government, or that they

should divide themselves into separate confederacies, and give to the head of each the same

kind of powers which they are advised to place in one national government. . . .

Federalist #10: James Madison

. . . If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle,

which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote. It may clog the

administration, it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its

violence under the forms of the Constitution. When a majority is included in a faction, the

form of popular government, on the other hand, enables it to sacrifice to its ruling passion or

interest both the public good and the rights of other citizens. To secure the public good and

private rights against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit

and the form of popular government, is then the great object to which our inquiries are

6

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment A (continued)

Constitution Debate Quotes

directed. Let me add that it is the great desideratum by which this form of government can be

rescued from the opprobrium under which it has so long labored, and be recommended to the

esteem and adoption of mankind. . . .

. . . The other point of difference is, the greater number of citizens and extent of territory

which may be brought within the compass of republican than of democratic government; and

it is this circumstance principally which renders factious combinations less to be dreaded in

the former than in the latter. The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct

parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more

frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of

individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed,

the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression. Extend the sphere,

and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a

majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if

such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own

strength, and to act in unison with each other. Besides other impediments, it may be

remarked that, where there is a consciousness of unjust or dishonorable purposes,

communication is always checked by distrust in proportion to the number whose concurrence

is necessary. . . .

. . . The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular States, but

will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other States. A religious sect

may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the Confederacy; but the variety of sects

dispersed over the entire face of it must secure the national councils against any danger from

that source. A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of

property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole

body of the Union than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is

more likely to taint a particular county or district, than an entire State.

In the extent and proper structure of the Union, therefore, we behold a republican remedy for

the diseases most incident to republican government. And according to the degree of

pleasure and pride we feel in being republicans, ought to be our zeal in cherishing the spirit

and supporting the character of Federalists.

Federalist # 38: James Madison

. . . A patient who finds his disorder daily growing worse, and that an efficacious remedy can

no longer be delayed without extreme danger, after coolly revolving his situation, and the

characters of different physicians, selects and calls in such of them as he judges most

capable of administering relief, and best entitled to his confidence. The physicians attend;

the case of the patient is carefully examined; a consultation is held; they are unanimously

agreed that the symptoms are critical, but that the case, with proper and timely relief, is so

7

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment A (continued)

Constitution Debate Quotes

far from being desperate, that it may be made to issue in an improvement of his constitution.

They are equally unanimous in prescribing the remedy, by which this happy effect is to be

produced. The prescription is no sooner made known, however, than a number of persons

interpose, and, without denying the reality or danger of the disorder, assure the patient that

the prescription will be poison to his constitution, and forbid him, under pain of certain

death, to make use of it. Might not the patient reasonably demand, before he ventured to

follow this advice, that the authors of it should at least agree among themselves on some

other remedy to be substituted? And if he found them differing as much from one another as

from his first counsellors, would he not act prudently in trying the experiment unanimously

recommended by the latter, rather than be hearkening to those who could neither deny the

necessity of a speedy remedy, nor agree in proposing one?

Such a patient and in such a situation is America at this moment. She has been sensible of

her malady. She has obtained a regular and unanimous advice from men of her own

deliberate choice. And she is warned by others against following this advice under pain of

the most fatal consequences. Do the monitors deny the reality of her danger? No. Do they

deny the necessity of some speedy and powerful remedy? No. Are they agreed, are any two of

them agreed, in their objections to the remedy proposed, or in the proper one to be

substituted? Let them speak for themselves. This one tells us that the proposed Constitution

ought to be rejected, because it is not a confederation of the States, but a government over

individuals. Another admits that it ought to be a government over individuals to a certain

extent, but by no means to the extent proposed. A third does not object to the government

over individuals, or to the extent proposed, but to the want of a bill of rights. A fourth

concurs in the absolute necessity of a bill of rights, but contends that it ought to be

declaratory, not of the personal rights of individuals, but of the rights reserved to the States

in their political capacity. . . .

. . . But waiving illustrations of this sort, is it not manifest that most of the capital objections

urged against the new system lie with tenfold weight against the existing Confederation? Is

an indefinite power to raise money dangerous in the hands of the federal government? The

present Congress can make requisitions to any amount they please, and the States are

constitutionally bound to furnish them; they can emit bills of credit as long as they will pay

for the paper; they can borrow, both abroad and at home, as long as a shilling will be lent. Is

an indefinite power to raise troops dangerous? The Confederation gives to Congress that

power also; and they have already begun to make use of it. Is it improper and unsafe to

intermix the different powers of government in the same body of men? Congress, a single

body of men, are the sole depositary of all the federal powers. Is it particularly dangerous to

give the keys of the treasury, and the command of the army, into the same hands? The

Confederation places them both in the hands of Congress. Is a bill of rights essential to

liberty? The Confederation has no bill of rights. . . .

8

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment A (continued)

Constitution Debate Quotes

Federalist #84: Alexander Hamilton

. . . The most considerable of the remaining objections is that the plan of the convention

contains no bill of rights. . . .

. . . It has been several times truly remarked that bills of rights are, in their origin,

stipulations between kings and their subjects, abridgements of prerogative in favor of

privilege, reservations of rights not surrendered to the prince. … It is evident, therefore, that,

according to their primitive signification, they have no application to constitutions

professedly founded upon the power of the people, and executed by their immediate

representatives and servants. Here, in strictness, the people surrender nothing; and as they

retain every thing they have no need of particular reservations. "WE, THE PEOPLE of the

United States, to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ORDAIN

and ESTABLISH this Constitution for the United States of America." Here is a better

recognition of popular rights, than volumes of those aphorisms which make the principal

figure in several of our State bills of rights, and which would sound much better in a treatise

of ethics than in a constitution of government. . . .

. . . I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and to the extent in which they are

contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed Constitution, but would even be

dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers not granted; and, on this very

account, would afford a colorable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare

that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why, for instance, should it be

said that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which

restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a

regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible

pretense for claiming that power. They might urge with a semblance of reason, that the

Constitution ought not to be charged with the absurdity of providing against the abuse of an

authority which was not given, and that the provision against restraining the liberty of the

press afforded a clear implication, that a power to prescribe proper regulations concerning

it was intended to be vested in the national government. This may serve as a specimen of the

numerous handles which would be given to the doctrine of constructive powers, by the

indulgence of an injudicious zeal for bills of rights. . . .

. . . There remains but one other view of this matter to conclude the point. The truth is, after

all the declamations we have heard, that the Constitution is itself, in every rational sense,

and to every useful purpose, A BILL OF RIGHTS. . . .

9

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment A (continued)

Constitution Debate Quotes

Anti-Federalist #84: Brutus (Robert Yates, New York), from New York Journal 11/1/1787

When a building is to be erected which is intended to stand for ages, the foundation should

be firmly laid. The Constitution proposed to your acceptance is designed, not for yourselves

alone, but for generations yet unborn. The principles, therefore, upon which the social

compact is founded, ought to have been clearly and precisely stated, and the most express

and full declaration of rights to have been made. But on this subject there is almost an entire

silence. . . .

. . . The common good, therefore, is the end of civil government, and common consent, the

foundation on which it is established. To effect this end, it was necessary that a certain

portion of natural liberty should be surrendered, in order that what remained should be

preserved. . . . But it is not necessary, for this purpose, that individuals should relinquish all

their natural rights. Some are of such a nature that they cannot be surrendered. Of this kind

are the rights of conscience, the right of enjoying and defending life, etc. Others are not

necessary to be resigned in order to attain the end for which government is instituted; these

therefore ought not to be given up. To surrender them, would counteract the very end of

government, to wit, the common good. From these observations it appears, that in forming a

government on its true principles, the foundation should be laid in the manner I before

stated, by expressly reserving to the people such of their essential rights as are not necessary

to be parted with. The same reasons which at first induced mankind to associate and institute

government, will operate to influence them to observe this precaution. . . .

. . . This will appear the more necessary, when it is considered, that not only the Constitution

and laws made in pursuance thereof, but all treaties made, under the authority of the United

States, are the supreme law of the land, and supersede the Constitutions of all the States. The

power to make treaties, is vested in the president, by and with the advice and consent of twothirds of the senate. I do not find any limitation or restriction to the exercise of this power.

The most important article in any Constitution may therefore be repealed, even without a

legislative act. Ought not a government, vested with such extensive and indefinite authority,

to have been restricted by a declaration of rights? It certainly ought.

So clear a point is this, that I cannot help suspecting that persons who attempt to persuade

people that such reservations were less necessary under this Constitution than under those of

the States, are wilfully endeavoring to deceive, and to lead you into an absolute state of

vassalage.

10

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment A (continued)

Constitution Debate Quotes

Anti-Federalist #60: John Mercer, Maryland Testimony to Members of the Ratifying

Conventions of New York and Virginia, 1788.

. . . And we conceive that there is no power which Congress may think necessary to exercise

for the general welfare, which they may not assume under this Constitution. And this

Constitution, and the laws made under it, are declared paramount even to the unalienable

rights which have heretofore been secured to the citizens of these States by their

constitutional compacts. . . .

Moreover those very powers, which are to be expressly vested in the new Congress, are of a

nature most liable to abuse. They are those which tempt the avarice and ambition of men to a

violation of the rights of their fellow citizens, and they will be screened under the sanction of

an undefined and unlimited authority. Against the abuse and improper exercise of these

special powers, the people have a right to be secured by a sacred Declaration, defining the

rights of the individual, and limiting by them the extent of the exercise. The people were

secured against the abuse of those powers by fundamental laws and a Bill of Rights, under

the government of Britain and under their own Constitution. That government which permits

the abuse of power, recommends it, and will deservedly experience the tyranny which it

authorizes; for the history of mankind establishes the truth of this political adage- -that in

government what may be done will be done. . . .

. . . When we turn our eyes back to the zones of blood and desolation which we have waded

through to separate from Great Britain, we behold with manly indignation that our blood

and treasure have been wasted to establish a government in which the interest of the few is

preferred to the rights of the many. When we see a government so every way inferior to that

we were born under, proposed as the reward of our sufferings in an eight years calamitous

war, our astonishment is only equaled by our resentment. On the conduct of Virginia and

New York, two important States, the preservation of liberty in a great measure depends. The

chief security of a Confederacy of Republics was boldly disregarded, and the Confederation

violated, by requiring 9 instead of 13 voices to alter the Constitution. But still the resistance

of either of these States in the present temper of America (for the late conduct of the party

here [Maryland] must open the eyes of the people in Massachusetts with respect to the fate of

their amendment) will secure all that we mean to contend for-the natural and unalienable

rights of men in a constitutional manner. . . .

11

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment A (continued)

Constitution Debate Quotes

Anti-Federalist Essay: John DeWitt (pseudonym, Boston American Herald, 10/27/1787

(Massachusetts)

. . . That the want of a Bill of Rights to accompany this proposed System, is a solid objection

to it, provided there is nothing exceptionable in the System itself, I do not assert. -- If,

however, there is at any time, a propriety in having one, it would not have been amiss here. A

people, entering into society, surrender such a part of their natural rights, as shall be

necessary for the existence of that society. They are so precious in themselves, that they

would never be parted with, did not the preservation of the remainder require it. They are

entrusted in the hands of those, who are very willing to receive them, who are naturally fond

of exercising of them, and whose passions are always striving to make a bad use of them. -They are conveyed by a written compact, expressing those which are given up, and the mode

in which those reserved shall be secured. Language is so easy of explanation, and so difficult

is it by words to convey exact ideas, that the party to be governed cannot be too explicit. The

line cannot be drawn with too much precision and accuracy. The necessity of this accuracy

and this precision encreases in proportion to the greatness of the sacrifice and the numbers

who make it. -- That a Constitution for the United States does not require a Bill of Rights,

when it is considered, that a Constitution for an individual State would, I cannot conceive. -The difference between them is only in the numbers of the parties concerned they are both a

compact between the Governors and Governed the letter of which must be adhered to in

discussing their powers. That which is not expressly granted, is of course retained. . . .

12

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment B

The Bill of Rights

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free

exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the

people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Amendment II

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the

people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

Amendment III

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the

Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.

Amendment IV

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against

unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but

upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place

to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Amendment V

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a

presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces,

or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person

be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb, nor shall be

compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public

use without just compensation.

13

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment B (continued)

The Bill of Rights

Amendment VI

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by

an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed,

which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature

and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have

compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the assistance of

counsel for his defense.

Amendment VII

In Suits at common law, where the value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right

of trial by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a jury shall be otherwise re-examined

in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.

Amendment VIII

Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual

punishments inflicted.

Amendment IX

The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or

disparage others retained by the people.

Amendment X

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the

States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

14

Natural Rights – Grade 11

Attachment C

Making the Federalist or Anti-Federalist Case

Directions: Imagine that the debate about ratifying the Constitution is occurring in the

present day, rather than the 1780s. You are a political consultant hired to advise either the

Federalists or the Anti-Federalists on how to communicate their position to the public. Select

either the Federalists or Anti-Federalists and write an essay that advises your clients:

1. Explain argument(s) they should use to convince the public that ratifying the proposed

constitution threatens or does not threaten Americans’ natural rights as outlined in the

Declaration of Independence. You must include at least two arguments for your client’s

position on the Constitution, and it must contain at least one relevant quotation from

either the Federalist or Anti-Federalist Papers.

2. Advise them which three communication tools they should use to make their case to the

public and why these are appropriate choices. You should justify each choice on the basis

of the communication tool’s usefulness in the present day.

3. Use appropriate vocabulary terms.

Scoring Guidelines:

4 points

Essay cites from Essay cites two

or more

Federalist or

Anti-Federalist arguments and a

relevant

Papers.

quotation

supporting their

position.

3 points

Essay cites one

argument and

one relevant

quotation

supporting their

position.

2 points

1 point

Essay cites either Essay has no

one argument or arguments or

one quote

quotes cited.

supporting their

position.

Essay includes

communication

tools and justifies

the choices.

Communication

tools are

mentioned but

justification is

weak.

Communication

tools are

mentioned but

not justified.

There is a

mixture of

specific

vocabulary and

more general

terms.

Ideas are

expressed using

vague or general

words.

Essay justifies

appropriate

choice of

communication

tools.

Essay includes

appropriate

communication

tools and justifies

the choices with

strong reasoning.

Vocabulary

Specific terms

Most terms are

are included and used correctly.

used correctly.

15