Moreland Integrated Transport Strategy

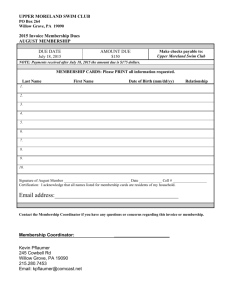

advertisement