Doryanthes AUGUST 2011

advertisement

Volume 4, Number 3, August 2011

Commemorating the 2500 years since the

Battle of Marathon

The “Soros” The Tumulus of the Athenians at Marathon

The Journal of History and Heritage

for Southern Sydney

ISSN 1835-9817 (Print) ISSN 1835-9825 (Online)

Price $7.00 (Aus)

1

Doryanthes

Exec. Editor: Les Bursill OAM

Doryanthes

.

The Gymea Lily (spec. Doryanthes excelsa) From Greek “dory”: a spear and “anthos”: a flower, referring to the

spear- like flowering stems; excelsa: from Latin excelsus: elevated, high, referring to the tall flower spikes.

Go to www.doryanthes.info

Editorial Policy;

Editorial Committee

Chair/Editor/Publisher: Les Bursill, OAM, BA

M.Litt UNE JP.

V/Chair: Garriock Duncan, BA(Hons) DipEd

Syd MA Macq GradDipEdStud NSW MEd

DipLangStud Syd.

Treasurer: Mary Jacobs, BEd Macq DipNat

Nutr AustCollNaturalTherapies.

Film Review Editor: Michael Cooke, BEc LaT

GradDipEd BA Melb MB VU.

Book Review Editor and Secretary: Adj. Prof.

Edward Duyker,

OAM, BA(Hons) LaT PhD

Melb FAHA FLS FRHistS JP.

Committee Members:

Sue Duyker, BEc BA(Asian Studies) ANU

BSc(Arch.) B Arch Syd.

Merle Kavanagh, DipFamHistStud

SocAustGenealogists AssDipLocAppHist UNE.

John Low, BA DipEd Syd DipLib CSU.

Index of Articles

Page

Number

Editorial – Garriock Duncan

3

McLeod Award Notes

4

Gleanings - Sue Duyker

5

The Soros at MarathonGarriock Duncan

7

1. All views expressed are those of the

individual authors.

2. It is the Policy of this Journal that material

published will meet the requirements of the

Editorial Committee for content and style.

3. Appeals concerning non-publication will be

considered. However decisions of the

Editorial Committee will be final.

Les Bursill OAM on behalf of the Editorial

Committee

Index of Articles

Page

Number

Cornelius Nepos: Life of Miltiades

Translated with an historical commentary -

23

Garriock Duncan

A Marathon Effort.

An Australian at the first Modern Olympics-

33

Merle Kavanagh

The First Marathon Race- Garriock Duncan 36

Marathon, Salamis and

Plataea- Garriock Duncan

Those Who Dare to Remain

In Place: Hoplite Warfare—the

Evidence from the Nicholson

Museum - Pamela Chauvel

10

Scattered Seeds - Garriock Duncan

37

Book Reviews. Richard A. Billows, Marathon –

15

Professor Edward Duyker

42

Film Reviews The 300 Spartans and 300 –

Michael Cooke

45

17 © and may not be reproduced without permission of the author.

The articles published herein are copyright

ISSN 1835-9817 (Print) - ISSN 1835-9825 (Online)

The publishers of this Journal known as “Doryanthes” are Leslie Bursill and Mary Jacobs trading as

“Dharawal Publishers Inc. 2009”

The business address of this publication is 10 Porter Road Engadine NSW, 2233.

Les.bursill@gmail.com www.doryanthes.info

2

The Email Address (until further notice) of this Journal is lesbursill@tpg.com.au

Editorial –

The Ritchie Memorial Lecture for 2010, delivered at Sydney University, and entitled

Marathon and the Persian Wars in the Imagination of the Greeks, was given by

Prof. John Marincola of Florida State University. In the preamble to his lecture,

Prof. Marincola identified 2011 as the 2500th anniversary of the Battle of Marathon

(see: www.danaxtell.com/marathonanniversary). A quick mathematical exercise

seems to indicate that 2011 is the 2501st anniversary. Reader, do not despair. The

fault is not yours but that of Dionysius Exiguus, the man responsible for our dating

system (see: R J Gould, Questioning the Millennium, 1997).

This edition of Doryanthes is the result of Prof. Marincola’s remark. Our original

intention was for the entire edition to concern aspects of the Battle. That proved

overly ambitious; it is now more accurate to say that this edition is inspired by the

Battle of Marathon. The Table of Contents will reveal an eclectic mix of topics

(including our regular features). We welcome a new contributor, Pamela Chauvel.

Pamela works in educational programs at the Nicholson Museum (Usyd). She has

written an article on hoplite warfare, based on material in the Museum. Two other

articles deserve mention: the first is the translation and commentary on Cornelius

Nepos, Life of Miltiades. As far as we can ascertain, this is the 1st English

translation since the Loeb Classical Library edition of 1929; secondly, the article by

Merle Kavanagh, linking the Battle, the modern Olympic Games and Australia’s first

Olympic medallist.

How decisive was the Battle? It does not rate a mention in any Persian source, just

another minor engagement on the edge of empire. However, for armchair warriors

of Victorian England, the Battle was a seminal event in world history, or that is how

Sir Edward Creasy (The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World from Marathon to

Waterloo, 1851: (http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/gutbook/lookup?num=4061) saw

it. Creasy’s argument is, today, somewhat muted by the fact that he wrote before

even the Crimean War, let alone the two World Wars or the wars of decolonialism

since the end of World War II. As is often stated, the true decisive outcome of

Marathon was the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC.

The Committee of Doryanthes would like to take this opportunity to make two

announcements. The first is very close to home. Regular readers would recognise

the name, Marika Low. Marika, the daughter of Committee Member, John Low, has

been our intermittent correspondent on topics relating to classical archaeology.

Earlier this year, Marika graduated from Sydney University with the degree of B.A.,

with 1st class honours in Archaeology. Marika is currently plying her trade as a

practitioner of Australian Archaeology in the Pilbara region, WA.

Secondly, the publication of this edition of Doryanthes has been generously

supported by a grant from the Classical Association of NSW, under the terms of

The Ian McLeod Award Program, 2011.

Garriock Duncan

3

The Ian McLeod Award for the Promotion of Classical

Studies (2011)

The chief object of the Classical Association New South Wales Inc. is to promote

the development of classical studies in New South Wales. The Association was

founded in 1909 and conducts a range of activities, including lectures, social

functions, workshops and a Latin and Greek reading competition for school

students. It sponsors the annual Sydney Latin Summer School and is the cosponsor of the journal Classicum. The Association has close links with similar

bodies in other states. For more information, see:

http://classics.org.au/cansw/index.html.

In 2011, the Classical Association of New South Wales established the annual Ian

McLeod Award to be first awarded in 2011. The Award will be granted to support a

project which will promote in New South Wales the study of the culture of the

ancient Mediterranean (before AD 700). The award is to give public recognition to

the efforts of Ian McLeod, longtime Hon. Secretary of CANSW, and, for many

years, Director of the Latin Summer School at the University of Sydney (both

positions till 2009).

The award will, in future, be awarded in the November of each year for a project to

be completed in the following year. Funds will be awarded on a competitive basis,

and the right to make no award on any occasion is reserved. The decision on

which application or applications to approve will be made by a subcommittee of the

Council of CANSW, consisting of the President or nominee, the Secretary, the

Treasurer and one other Council member.

Within the overall context of promoting these objects, the Ian McLeod Award will be

given to a project which in the judgment (and the absolute discretion) of the

subcommittee either promotes classical studies via the press or electronic media,

or promotes and advances classical studies in schools (at any level or all levels

from Kindergarten to Year 12), or promotes and advances classical studies in adult

and community education.

Doryanthes’ Project Submission:

We are a community based magazine published quarterly since November (2008). It has a

small print run of 35 copies (distributed mainly to institutional libraries) with an on-line

mail out of 800+ copies. Past editions can be viewed at: www.doryanthes.info and click on

archive), The magazine is not specifically a classical studies magazine but has increasingly

published articles of classical interest.

Funding is sought for the publication in August, 2011, of a commemorative edition devoted

to the Battle of Marathon. We seek a sum of $900 to publish an additional 100 print copies

for distribution to local high schools.

Our submission was approved on May 2, 2011.

4

Gleanings

With Sue Duyker

Gleanings from the Ancient World (August 2011)

The Etruscans: A Classical Fantasy

From 6 July 2011, Nicholson Museum, University of Sydney, southern entrance to the Quadrangle,

Manning Rd, Camperdown

In popular imagination the Etruscans are the very stuff of fantasy, myth and legend. Who are they, where did

they come from, what does their language mean? In reality, although wiped out or assimilated by Rome, they

have left us an extraordinarily rich heritage of art, jewellery, metal working, terracotta sculpture, urban

planning, walls, and roads. Indeed, in the 6th century BC, the Etruscans were the most powerful people in

the Mediterranean. So what went wrong?

www.sydney.edu.au/museums/events_exhibitions/nicholson_exhibitions.shtml

Image: Details of a wall painting from the Tomb of the Leopards, Tarquinia, 5th century BC.

The Philo and the Jewish Community at Alexandria

07:05pm, Tuesday 6 September 2011, Macquarie University, W6A308

In conjunction with Sir Asher Joel Foundation, Professor Sarah Pearce (University of Southampton): The

Philo and the Jewish Community at Alexandria. Professor Pearce is brought to Australia courtesy of ANU.

For information contact SSEC@mq.edu.au

Higher School Certificate Study Days for Greek & Roman Topics

Saturday 17 September 2011, Macquarie University

Greek & Roman Topics for the HSC.

For information contact Macquarie Ancient History Association (MAHA)

newsletter@ancienthistory.com.au

5

Diolkos for 1500 Years

The Diolkos was a paved trackway which enabled boats to be moved overland across the Isthmus of

Corinth. The shortcut allowed vessels to avoid the long dangerous sea route around the Peloponnese

peninsula.

The main function of the Diolkos was the transfer of goods, although in times of war it also became a

preferred means of speeding up naval campaigns. It operated from circa 600 BC until the middle of the 1st

century AD. The scale on which the Diolkos combined the two principles of the railway and the overland

transport of ships was unique in antiquity.

Photos of the remains of the Diolkos and details of the campaign to save this ancient monument are here:

www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.427804384101.226818.660439101&l=3d11aff07f

“Diolkos for 1500 Years” is an animated documentary short depicting the transport of a small 4th century BC

merchant vessel over the ancient diolkos portage road. The film was initiated by the Society of Ancient

Greek Technology, produced by the Technical Chamber of Greece, and directed by T.P. Tassios, N. Mikas,

and G. Polyzos. It is available on YouTube in Greek and English versions. See the link, below.

corinthianmatters.com/the-isthmus/the-diolkos/diolkos-links-and-videos/

Marathon Commemorative Coin, Australia

The Perth Mint has marked the 2500th anniversary of the Battle of Marathon with the issue of a

silvercommemorative coin.

www.perthmint.com.au/catalogue/pheidippidis-marathon-run-2500th-anniversary-490bc-2010-1oz-silverproof-coin.aspx

Finally, take advantage of the high Australian Dollar with this tempting event:

Athens Classic Marathon 2011

Sunday 13 November 2011, starting at 9:00am

The Athens Classic Marathon takes place on the reputed route where the agile Pheidippides ran with news

of the victory of the Greeks over the Persians. The young man ran the 42 km from the battlefield to the

capital as fast as he could, announced his joyous message, and died.

The course of the Athens Classic Marathon gives you the possibility to challenge yourself and be part of

history at the same time. For runners who wish to experience history but don’t fancy a 42km run in hilly

Attica, the Athens Classic Marathon also features a 5km and a 10km run starting and finishing at the stadium

in Athens.

Registration www.athensclassicmarathon.gr/marathon/fmain.aspx

6

The Soros at Marathon

Garriock Duncan

Regular readers of Doryanthes will notice a change in our front cover. For this edition, the

image of the doryanthes has been rested and instead, readers will see a photo of the

Soros at Marathon. As used by Herodotus (1.68.2, 2.78)1, soros has the meaning, coffin.2

This meaning, according to my modern Greek correspondent, is retained to this day.

However, when driving into Marathon, do not look for a sign pointing to the Soros of

Marathon. For modern Greek uses tymbros to denote the mound. So, look for the

Tymbros of Marathon. Tymbros (LSJ, q.v., p. 1834a) is another classical Greek survivor

and is probably a more precise term, since its standard English meaning is burial mound

or tomb (see: Hdt, 1.45.3).

Greek hoplite warfare was a stylised experience and once the battle was over (the

defeated having acknowledged their defeat), the tidying up of the battlefield took place. 3

This, of course, mainly meant dealing with the victims of both sides. The enemy dead

would receive little attention. At Marathon, the Persian dead were left unburied for several

days, since the late arriving Spartans were able to view the Medes (Hdt., 6.129).

Eventually, the bodies were tossed into a nearby ditch, the location being lost till 1884/5. 4

The Athenians were unable to savour their victory long. The Persians appear to have had

a back up plan. For they sailed to Athens in the hope of effecting a landing at Phaleron

before the Athenian force could return (Hdt., 6. 115). Miltiades force marched nine of the

ten tribal regiments back to Athens to oppose the likely Persian landing (Hdt., 6.116.1) The

tenth, under the command of Aristides was left to guard the battlefield (Plutarch [Plut.].,

Aristides, 5 [pp. 114-115]).5

Thucydides, in his introduction to the funeral speech of Pericles (2.35-2.46) describes the

usual method, by which Athens buried her military dead (2.34).6 As outlined by

Thucydides, the bodies were brought back to Athens for burial. There was a signal

exception - those, who fell at Marathon: for their singular and extraordinary valour [they]

were interred on the spot where they fell (2.34.5). No doubt, this service was carried out

by Aristides and the regiment of the Antiochis tribe. They buried the dead and raised a

temporary trophy to the victory.7

Today, the burial site is crowned by the soros.8 When the mound was raised is a matter of

debate.9 However, Pausanias does add some additional information - the mound was

surmounted by stelai , inscribed with the names of the dead, arranged by tribe (2.32.3).

1

References to Herodotus (henceforth cited as Hdt) are to: The Landmark Herodotus, ed. R B Strassler, Pantheon

Books, New York, 2007.

2

H G Liddell & R Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, 9ed., rev. H S Jones, OUP, 1940 (henceforth cited as LSJ), q.v., p.

1621a.

3

V D Hanson, The Western Way of War, Hodder & Stoughton, 1989, pp. 197-209.

4

See: B Petrakos, Marathon, The Archaeological Society at Athens, 1996, pp. 24-25. Some 640 years after the battle,

when he visited the site, Pausanias was unable to locate the grave of the Persians (1.32.4). References to Pausanias are

to: Pausanias, Guide to Greece 1: Central Greece, Penguin Classics, 1971.

5

All references to Plutarch are to: Plutarch, The Rise and Fall of Athens, Penguin Classics, 1960.

6

References to Thucydides are to: The Landmark Thucydides, ed. R B Strassler. Free Press, 1996.

7

Petrakos, op. cit., pp. 26-27. Eventually, a memorial of white marble would be erected (Pausanias1.32.4).

8

Petrakos, op. cit., pp. 18-21.

7

No doubt, the disgrace of Miltiades in 489 (Hdt., 6.135; Nepos, Miltiades, 7) had an

adverse effect on the renown of Marathon. However, there would be other memorials to

the battle. These result from a concerted program of Cimon’s to assert the glory of

Marathon and, hence, rehabilitate the reputation of his father, Miltiades.10 There were

helmet dedications in the Athenian Treasury at Delphi11; the Marathon base built against

the Athenian Treasury12; the inclusion of a statue of Mitliades in the monument of the

Eponymous Heroes in the Agora at Athens (Pausanias, 10.10.1)13; the great Marathon

painting in the Stoa Poikile in the Agora (Pausanias, 1.15.3)14; and the south frieze of the

temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis,15

However, there is another very evocative memorial to Athens. The great Athenian

tragedian, Aeschylus, fought in both Marathon and Salamis. Yet his great historical

tragedy on the Persian Wars, The Persians, is not about Marathon but Salamis.16 Indeed,

it is possible that the first Greek ship to ram an enemy vessel at Salamis was that of

Aeschylus’ brother, Ameinias.17 Yet when Aeschylus, reportedly, came to write his own

epitaph, the only thing he chose to mention of his life was his presence at Marathon. 18

This tomb in wheat-bearing Gela covers the dead Aeschylus, [son] of Euphorion,

from Athens; the grove of Marathon can vouch for his famed valour, and the longhaired Mede who knew it well.19

Indeed, the site at Marathon retained such a special magic that it was still obvious when

Pausanias visited some six hundred years after the battle:

The country district of Marathon, halfway between Athens and Carystus in

Euboea, is where the barbarians landed in Attica, were beaten in battle, and lost

some ships as they retreated. The grave on the plain is that of the Athenians;

there are stones on it carved with the names of the dead in their tribes. The

other grave is that of the Plataeans, Boeotians, and slaves: this was the first

battle in which slaves fought.

One man, Miltiades, has a private memorial; he died later after failing at Paros

and standing trial at Athens. Here every night you can hear the noise of

whinnying horses and of men fighting. It has never done a man good to wait

there and observe this closely, but if it happens against a man’s will the anger

of the demonic spirits will not follow him. The people of Marathon worship as

heroes those killed in the battle (1.32.3-4).

9

P Krentz ( The Battle of Marathon, Yale UP, 2010, p. 170) argues that the mound was raised quite soon after the

battle, basing his decision on the date of pottery found in the mound.

10

See: S Hornblower, The Greek World, 479-323 BC, 4ed, Routledge, 2011, pp. 18-19.

11

R B Strassler, ed., The Landmark Herodotus, Pantheon Books, New York, 2007, fig. 6.117a (p, 476).

12

For the text, see: C Fornara, Archaic Times to the End of the Peloponnesian War, John Hopkins UP, 1977, no. 50

(pp. 49-50). For the treasury, see: M Andronicos, Delphi, Ekdotike Athenon, 2002, pp. 24, 25, 26.

13

On the monument, see: The Athenian Agora, American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1976, pp. 69, 70-72.

14

On the Stoa Pokile (the Painted Stoa), see: J Camp, The Athenian Agora, Thames and Hudson, 1986, pp. 69-71; and

The Athenian Agora, pp. 102-103.

15

J Hurwitt, The Acropolis in the Age of Pericles, CUP, 2004, p. 86, and. figs. 74-75 (p.85)

16 On the play, see: T W Hillard, “Aeschylus' Persae as Theatre”, Ancient History, 20(1), 1990, pp.6-15. For

the text with commentary, see: H D Broadhead, The Persae of Aeschylus, CUP, 1960, and translation and

commentary: A J Podlecki, Aeschylus, The Persans, Bristol Classical Press, 1991.

17

This identification is not certain. See: Podlecki, op. cit., n. 9 (p. 120).

18

Another brother, Cynegeiros, was killed At Marathon in the melee round the Persian ships (Hdt., 6.114).

19

The translation is Petrakos’ (op. cit., p. 46). Also, see: R A Billows,Marathon, Overlook /Duckworth, 2010, pp.34-35.

8

In a little under four years will occur the100th anniversary of the Gallipoli landing. We, in

Australia, have, in a way, copied the Athenians. They, too, so impressed by the

achievement, coined a special word to describe those, who fought at Marathon,

Marathonomaches, (lit. “the fighter of/at Marathon”).20 The word acquired iconic status.

Aristophanes’ usage indicates its currency,21 Though by the time of Aristophanes any

surviving Marathon fighters would have been very elderly gentleman, even by our

standards let alone those of the Athenians. By the time Pausanias arrived at Marathon,

the celebrations of the victory were entering their seventh century. I wonder how Australia

will still be celebrating the Gallipoli landing in another six hundred years.

In a speech given in Sparta in 432/1 prior to the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War,

some Athenian envoys describe the contribution of Athens to Greek victory in the Persian

Wars. The envoys are keen to get across to the Spartans the extent of the Athenian

contribution to the final victory over the Persians, though somewhat expectedly the envoys

concentrate on Salamis rather than Plataea. In this context, there is not much scope to

dwell on Marathon. However, in their preamble, as it were, to their comments on Salamis,

there is a brief comment on Marathon—brief but significant:

We need not refer to remote antiquity…But to the Persian wars and the

contemporary history we must refer…We assert that at Marathon, we were in

the forefront of danger and faced the barbarian by ourselves (Thuc.,

1.73.2, 4).

Marathon was never a Greek victory, it was always an Athenian victory. Today, the only

monument to that victory, virtually intact, easily accessible and open to all, is the Soros at

Marathon.

The Tymbros at Marathon

20

LSJ, q.v., p. 1080b. Interestingly, it seems that those Athenians, who fought at Salamis, were not deemed worthy of

a similar honour. There is no word, Salaminomaches. At least, LSJ does not list one (see p. 1581b).

21

Billows, op. cit., pp. 35-37; Krentz, op. cit., p. 177; Petrakos, op. cit., n. 56 (p. 187).

9

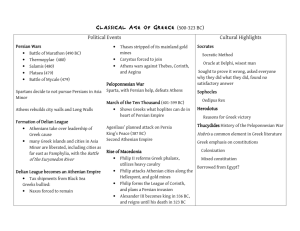

Marathon, Salamis and Plataea—a Survey of

the Period, 490-479.

Garriock Duncan

The purpose of this edition of Doryanthes is to commemorate the 2500th anniversary of the

Battle of Marathon. However battles do not occur in isolation but must be seen in context.

So, the purpose of this introductory article is to sketch that context. I must supply a

caveat, however. Though in honour of Marathon, this edition of Doryanthes will contain no

detailed account of the battle.22

In my title, I omit the Battle of Thermopylae. While Thermopylae is, of course, a stirring

example of courage and duty in the face of overwhelming odds, the battle had no lasting

geo-political significance.23 Contrast this with the Battle of Salamis. Athens’ victory at

Salamis (in 48024) triggered off an explosion of creativity for the next fifty years—as

recorded in the Pentakontaetia of Thucydides25. Most of what you, readers, know of

Ancient Greece probably happened in this fifty year period. It spawned drama, history,

democracy and the Acropolis complex, with the

Parthenon as its centre piece.26

We are told we live in one of those seminal points

in history, when vast historical forces collide, i.e. a

“Clash of Civilizations”, the outcome of which will

determine the course of future history.27

Unfortunately, since we are living through the

clash, we lack the appropriate detachment to

pronounce on the validity of the claim. However,

such clashes have occurred previously. One

such clash was the succession of the wars

between the Persians and the various Greek states in the 5th and 4th centuries. This

period of conflict ended only with the decisive defeat of the Persian King, Darius III, at the

Battle of Gaugamela in 331, or perhaps with the death of Alexander the Great in 323.28

The Persian Empire began in c. 550, when Cyrus, a Persian prince, rebelled against his

Median overlord, Astyages (Herodotus [Hdt.], 1.123-130).29 The Persian Empire was an

expansive one and came into contact with the Greeks, when Cyrus overwhelmed the

22

For readers, who wish to know more, I have supplied extensive notes. The works cited therein range from

the popular to the scholarly. Additionally within the text, I have supplied references to the major ancient

authorities.

23 The battle did spawn the execrable film, 300. For a review, see: P Byrnes, “In the name of freedom”, Arts

and Entertainment, p. 15, in The Sydney Morning Herald. Weekend Edition, April 6-8, 2007.

24 All dates are BC.

25 Thucydides [Thuc.], 1.89-118. References to Thucydides are to: The Landmark Thucydides, ed. R B

Strassler. Free Press, 1996. For a convenient text (with commentary), see: A French, ed., The Athenian Half

Century, Sydney UP, 1971.

26 See the comment by Burn: A R Burn, Pericles and Athens, English Universities Pres, 1948, p. 114.

27 See: S P Huntingdon, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order, Simon & Schuster,

1966. For a historical survey of clashes, see: A Pagden, Worlds at War, Random House, 2008.

28 Eg: J Cassin-Scott, The Greek and Persian Wars, 500-323 BC, Men-at-Arms Series, Osprey, 1977.

29 References to Herodotus are to: The Landmark Herodotus, ed. R B Strassler, Pantheon Books, New York,

2007) History calls Cyrus, Cyrus the Great, and he is probably better known from his appearance in the Old

Testament. See: T A Bryant, ed., The New Compact Bible Dictionary, Zondervan Publishing House, 1967,

“Cyrus”, q.v., p.p. 121b-122b; J M Court, ed., Dictionary of the Bible, Penguin, 2007, “Cyrus”, q.v., pp. 65-66.

10

Lydian Empire of Croesus (Hdt., 1.77-79.2-3). The Persians were content to exercise a

loose control over their subject. The next stage in the narrative came with the emergence

of Darius.30 The precise nature of Darius’ links with the previous dynasty is unknown.31

However, Darius claimed

descent from Achaemenes,

the legendary progenitor of

the Persian royal family (Hdt.,

1.125.2). By the end of the 6th

century, the Persians had

crossed over into Europe and

established a foothold in

Thrace (Hdt., 4.96, 118).

Behind this frontier, in Ionia,

the Persians had appointed

absolute rulers to exercise

control over the Greek

subjects of the Empire.32

Several of these rulers had

been entrusted to guard the

bridge across the Hellespont,

by which Darius’ forces had

Hoplite Phalanx and below the Persian Enemy

crossed over into Europe.

One of them, Histaeus (Hdt.,

5.32.2-4), had ambitions of

the tyranny of Naxos. His

plans seem to have been

exposed and in an attempt to

evade punishment, he

persuaded his son-in-law,

Aristagoras (Hdt., 5.35-36) to

rebel against the Persians.

This revolt is better known as

the Ionian Revolt.33 Athens

and Eretria, on the island of

Euboea, unwisely become

involved in this revolt of

Persia’s Greek subject (Hdt.,

5.99). The high point of the

revolt was the attack on

Sardis, the Persian administrative centre for the region. The lower town, but not the

citadel was captured. However, the temple of the Great Mother (Cybele) was accidentally

burnt to the ground (Hdt., 5.101-102). The Greeks would come to rue this accident.

Thereafter, Athens and Eretria withdrew from the revolt. The Greeks were finally defeated

at the Battle of Lade in the harbour of Miletus, in 494 (Hdt., 6.14-18).

Darius also rates a mention in the Old Testament. (Bryant [n.8], “Darius”, q.v. 2, , p. 126b).

See: Hdt., 3.70, 71-73, 76-79, 85-87.

32 The correct term for these rulers is “tyrants”. However, the word does not yet have the pejorative sense

acquired later (A Andrewes, The Greek Tyrants, Hutchinsons University Library, 1974, pp. 20-30). The term

was first applied to the Lydian ruler, Gyges. (Hdt.,1.8-14; Andrewes, op. cit, n. 10, p. 155). See, also: C W

Fornara, ed., Archaic Times to the End of the Peloponnesian War, John Hopkins UP, 1977, n. 8 (p. 11).

33 A R Burn, The Pelican History of Greece, Penguin, 1965, pp. 157-158; N G L Hammond, History of Greece

to 323 BC, OUP, 1959, pp. 204-207.

30

31

11

After the suppression of the revolt in 494, the Persian King, Darius planned a revenge

attack on Athens and Eretria (Hdt., 5.105, 6.94). His initial attempt, in 492, ended in

disaster on the northern Greek coast near Mt. Athos (Hdt., 6.44.2-3). A second attempt,

two years later, saw the Persians landing on the northern coast of Attica at Marathon. The

Persians had the advantage of local knowledge. Hippias, the last Pisitratid tyrant of

Athens, was accompanying them (Hdt., 6.102, 107). It was on his advice that Marathon

was chosen. Hippias’ father, Pisistratus, had landed there at the beginning of his last and

successful attempt to become tyrant of Athens.34

The Athenians sought help from the Spartans but this was not forthcoming because of the

Spartans’ religious scruples. The only assistance, the Athenians would receive, was a

force of 1000 hoplites from Plataea. A hoplite force, under the overall command of

Callimachus, the Archon Polemarch, marched north to confront the Persians. There were

several days of inactivity and discussion on the part of the Athenians, As the Persians

were about to withdraw and crucially, it seems, after the Persian cavalry had already reembarked, the Athenians, on the day under the command of Miltiades, one of the new

tribal generals (strategoi), attacked (Hdt., 6.104-111). A feature of the battle was the

hoplite charge at the run against the Persian ranks, no doubt to minimize the danger

afforded by the Persian archers (Hdt., 6.112).35 The Athenians shattered Darius’ ambition

(Hdt., 6.113-114.36 A subsequent attempt by the Persians to attack Athens from the sea

was thwarted when Miltiades led nine of the ten regiments on a forced march back to

Athens (Hdt., 6.116). The tenth, under the command of Aristides was left to guard the

battlefield (Plutarch [Plut.]., Aristides, 5 [pp. 114-115]).37

It would be ten years before the Persians, now ruled by Darius’ son, Xerxes, would return..

However, during that ten year period, the Athenians had made a truly bold decision to

forego the pretence of being a land power, probably because of Sparta’s dominance in

that area, and to become a sea power. In 483, an unexpected financial windfall was

spent not on enlarging the hoplite force but instead on a significant expansions of Athens’

naval resources (Hdt., 7.143-144).38 The stage had been set for the battle of Salamis.

In 480, Xerxes returned to demand the submission of all mainland Greece. In a rare

display of unity, the major Greek states met in congress at Corinth to form a military

alliance, the pan- Hellenic League, the command being entrusted to Sparta, to reject the

Persian demand (Hdt., 7.172). 39 Xerxes’ invasion began in 480. A combined land and

sea invasion force moved into Greece from Persian controlled territory to the north of

Greece. The first major Greek opposition was at Thermopylae (Hdt., 7.200-239).40

34

On the Pisistratid tyranny, see: Andrewes, pp. 100-115; W G Forrest, The Emergence of Greek

Democracy, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1966, pp. 175-189; J D Smith, Athens under the Tyrants, Bristol

Classical Press, 1989.

35 Krentz disputes this. He argues that the charge was to negate the influence of Persian cavalry, i.e the

Persian cavalry had not yet re-embarked (P Krentz, The Battle of Marathon, Yale UP, 2010, pp. 143-152).

36 R A Billows, Marathon, Overlook Duckworth, 2010; Krentz; A Lloyd, Marathon, Souvenir Press, 2004; N

Sekunda, Marathon, 490 BC, Osprey, 2002. Books on Marathon often have highly emotive subtitles:

Billows, “How one Battle Changed Western Civilization”; Lloyd, “the story of civilizations on (a) collision

course. This is not exclusive to Marathon; cf. the subtitle of Strauss (B Strauss, The Battle of Salamis, Simon

& Schuster, 2004), “the naval encounter that saved Greece—and western civilization”.

37 All references to Plutarch are to: Plutarch, The Rise and Fall of Athens, Penguin Classics, 1960.

38 Also Aristotle, Constitution of Athens, 22.7 (Penguin Classics, 1984); Plut., Themistocles, 4 (p. 80). See: J

Hale, Lords of the Sea, Penguin, 2009, pp. 12-14.

39 The Greeks may not have been united as imagined. See my article, “Greek Disunity in the Persian Wars”,

Teaching History, 27(3), 1993, pp. 9-10.

40 E Bradford, Thermopylae, MacMillan, 1980; P Cartledge, Thermopylae, Pan, 2006; R Matthews, The

Battle of Thermopylae, The History Press, 2006.

12

A scratch force from several Greek states barred the Persian advance along the narrow

coastal plain. After days of skirmishing and a minor naval engagement at nearby

Artemisium (Hdt 8.1-11, 14-18)41, the Persians were able to turn the Greek position. A

small rearguard, composed principally of Spartans, held the pass to the last man to enable

the majority of the Greek force to escape.

The Spartans wished to abandon all of Greece

north of the Isthmus of Corinth, but meanwhile

the combined Greek fleet had taken up

positions around the island of Salamis The

Spartan admiral, Eurybiades, was no match for

the guile of the commander of the Athenian

contingent, Themistocles. Themistocles was

able to convince the Persians to attack the

combined Greek fleet, on terms favourable to

the Greeks. The resulting Greek victory at

Salamis was so decisive that Xerxes

immediately returned to Persia after the battle

(Hdt., 8.40-122).42 The Persian army was left to

retire north without the support of Persian naval

forces.

The next year, 479, the Persian army was

brought to bay near the Boeotian town of

Plataea (Hdt., 9.19-20).43 For once, the

Spartans did not have any religious festivals to

attend to and were able to field their full force.

The resulting battle was a total victory for the

Greeks. However, the unity which had

prevailed over the Persians at Plataea quickly

began to fragment and future battle lines began

to emerge. Since Salamis, the Greek naval

forces, now under the practical command of

Athens, had pursued the retreating remnants of

the Persian navy across the Ionian sea and

utterly destroyed them at the Battle of Mycale

(Hdt., 9.90-107). This Greek victory at Mycale

decisively tipped the balance of power in the

favour of the Greeks.

The Serpent Column – the

symbol of Greek Unity

After Mycale, all pretence of Greek unity was

abandoned and Athens assumed control of the

now naval war against the Persians. Sporadic

fighting (principally the Battle of the Eurymedon River in 469 (Thucydides [Thuc.],

1.100.1)44 and the expedition to Egypt in 459 (Thuc., 1.104.1, 110)45 between the Delian

41

Hale, op.cit., pp. 45-51.

H D Broadhead, The Persae of Aeschylus, CUP, 1960, pp. 322-339;Hale, pp. 55-71; V D Hanson, Why

the West has Won, Faber & Faber, 2001, pp. 27-59; R Nelson, The Battle of Salamis, William Lumbscombe,

1975; Strauss, n. 15; W Shepherd, Salamis, 480 BC, Campaign Series, Osprey Publishing, 2010.

43 T Lendvai, “The Battle of Plataea, Pt. 1”, Teaching History, 37(3), 2003, 4-14; ibid, “The Battle of Plataea,

Pt. 2”, Teaching History, 37(4), 2003, 56-61.

44 Hale (n. 17). 92-94.

45 V Ehrenberg, From Solon to Socrates, Methuen, 1973, 214; Hale (n. 17), pp. 99-103, 107-108; S

Hornblower, The Greek World, 479-323 BC, Methuen, 1983, pp, 40-42.

42

13

League and the Persians continued for a number of years. This active phase of the Greek

and Persian Wars was finally concluded by the Peace of Callias in c.449.46 Any future

conflict between Greek and Persian would take place in Persian territory. 47 Gradually that

rift developed between the two former allies, Athens and Sparta, which Thucydides

recognized as the true cause of the Peloponnesian War, 431-404 (Thuc., 1.23.6).48

Astute readers will have noticed that I have gone well beyond my remit, beyond 479.

There are a number of dates used to mark the end of the Persian Wars. 49 However, the

traditional way of dividing Greek history into specific historical episodes chooses 479 as

the dividing point between the Persian Wars and the next phase of Greek History. 50

However, the date is not some modern intrusion. In fact, it was chosen by Herodotus.

Herodotus was not a contemporary writer. He was writing some forty years later than the

events he described. With the benefit of hindsight, he was able to appreciate a

significant change had occurred in Greek history. 51The Hellenic League had been formed

to fight for the freedom of the Greeks. The Hellenic League had collapsed in 479. The

Spartans withdrew and Athens acquired control of what would become the Delian League,

i.e. the alliance of Athens and her allies. What once had fought to free the Greeks, now

became the instrument of their enslavement (cf. Thuc., 6.76.3). Herodotus wisely chose

to cease his enquiries at 479. Henceforth, the dominant issue of Greek history is the

expansionist policies of Athens, with their impact upon the interpretation of Greece’s

history, whether it be previous or current.52

The Stoa in the Agora at Miletus

46

See: Ehrenberg op.cit., n. 74, pp. 445-446; Hale op.cit., pp. 108-109; G M de St Croix, The Origins of the

Peloponnesian War, Duckworth, 1972, pp. 310-314.

47 Thereafter, Persian involvement in Greek affairs was diplomatic and financial not military. Determined

military conflict between the Greeks and the Persians did not begin again until the rise of the Macedonian

kingdom in the mid 4th century B.C.

48 See: D Kagan, The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War, Cornell UP, 1969; de St. Croix.

49 See Cassin-Scott, op.cit. and: P de Souza, The Greek and Persian Wars 499-386 BC, Essential Histories

36, Osprey, 2003.

50 See the following titles: Hornblower op.cit; P Osborne, Greece in the Making, 1200-479 BC, Routledge,

1996

51 Osbourne, op cit,, pp. 351-352.

52 See my article: “Inscriptions and the Politics of the Persian Wars”, Doryanthes, 2(1), February, 2009, pp.

33-39.

14

Those Who Dare to Remain In Place:

Hoplite Warfare—the Evidence from the

Nicholson Museum

Pamela Chauvel

…the Athenians came on, closed with the enemy along the line, and fought in a

way not to be forgotten. They were the first Greeks, so far as I know, to charge at

a run, and the first who dared to look without flinching at Persian dress and the

men who wore it53

In 490BC a force of 10 000 Athenians and 1 000 Plataeans, outnumbered three to one,

not only defeated the Persian army, but did so with comparatively low fatalities, 192 dead,

compared to 6400 Persian deaths. This victory on the Plain of Marathon highlighted the

superiority of hoplite armour and techniques when facing a lighter armed and less

cohesive army.

But what was it really like for the men who fought in the Greek phalanx, who stood in their

ranks and faced the bristling spears and flashing bronze shields of the enemy across the

plain? Soldiers, fighting under Greek summer sun, faced dust from thousands of feet,

entering eyes and mouths, obscuring vision already restricted by cumbersome helmets.

As they held their spears high and raised their heavy shields did they feel fear or did they

focus on holding their place in the phalanx until finally one side broke through and the

defeated succumbed to panic and confusion?

So let each man hold to his place with legs well apart,

Feet planted on the ground, biting his lip with his teeth….

Covered by the belly of his broad shield

In his right hand let him brandish his mighty spear

Let him shake the fearsome crest upon his head54

Although the Spartan poet Tyrtaeus was writing in the 7 th century, the fragments of his

poetry that survive have resonance for hoplite warfare.

In the sources there are only limited descriptions of battles from a soldier’s point of view.

What took place was different from battle to battle and a composite picture can only be

inferred from evidence which comes from three sources: archaeological, the actual armour

and weapons found; written accounts; and depictions on vases and artworks.

The Nicholson Museum at the University of Sydney contains several artefacts depicting

warriors fighting, or going off to war. The images are idealized and heroic. An example is

the Antimenes Amphora (Fig 1), which depicts a mythical scene, yet has the characters

equipped with armour and weapons of the 6th century. The scene is of Herakles, wearing

his characteristic lion skin, fighting Kyknos, son of Ares. In the middle stands Zeus, on the

left supporting Herakles is the goddess Athena, and to the right, fighting with his son, is

Ares. Both Kyknos and Ares wear a bell cuirass, greaves, a short kilt and a Corinthian

helmet, although with different styles of crest. A lock of Kyknos’s long hair trails down his

back. Typical of hoplite battles, the weapons being used are thrusting spears. The artist

has indicated the outcome by having Herakles’ spear already piercing the shield of

Kyknos, and even more subtly, by the way the figures are standing. Herakles and Athena

53

54

Herodotus, The Histories, 6.113, translated by Aubrey de Selincourt (Penguin, 1954).

Tyrtaeus, fr.11. 21-22, 24-26 in Andrew M. Miller, Greek Lyric: An Anthology in Translation (1996).

15

Fig. 1: Antimenes Amphora (NM71.1), 525-500 BC

lean forward, their weight on their front foot,

bodies open. Kyknos and Ares have their weight

on the back foot, shield up in a defensive

position. It is evident that Herakles, the hero, will

win.

Interestingly, Herakles and Kyknos are carrying a

Boeotian shield. No actual version of this type of

shield has been found yet it seems to be

associated in artworks with heroic scenes, and

pre-dates the round hoplon shield. The Dipylon

shield on the Geometric krater (c.750-725BC)

from the Nicholson Museum (fig 2) could be an

earlier type of shield or a different artistic depiction

of it. On the Antimenes Amphora, Athena and

Ares hold round hoplon shields. Both Boeotian

and hoplon shields employ an inner arm and hand

grip but because of the different shield shapes,

Herakles’ left arm is outstretched while Athena’s is

bent.

Fig. 2: Dipylon Krater (NM46.41)

750-725 BC

16

Fig. 3: Fragment of an Attic Cup with Warriors Fighting (NM56.12).

The double grip was an

innovation that played an

important role in the changing

nature of military engagement

in Greece. Now the weight

could be distributed by placing

the left forearm through a

metal band in the centre

(porpax) and holding a leather

hand grip (antilabe) at the rim.

The cup fragment (fig 3)

shows the inside of the shield

and its distinctive grip. The

Fig. 4: Attic Cup Fragment, Warrior farewelling his

warriors’ stance is

characteristic of artistic

wife (NM56.18)

representations of military

engagement, a wide legged stance with left foot forward. The shield was made of wood,

often faced with bronze, measured about 1m, across and weighed about 7kg. The extra

support provided by the porpax enabled the warrior to wield heavier shields than

previously. In addition, the deeply concave shape allowed the bearer to rest the shield on

his shoulder, holding it at an angle slanted away from the body as shown in fig 4. This cup

fragment from Attica depicts a warrior farewelling his wife. He wears a crested Corinthian

helmet and carries a long thrusting spear.

The thrusting spear was the main weapon of the hoplite soldier. As a back up he would

also carry a short stabbing sword. Spears were about 8 foot long with a butt spike or

17

sauroter (“lizard killer”), useful as a back up when one’s spear broke. A bronze spear

head from the Nicholson museum (fig 5) is socketed with a central rib and measures about

20cm

Fig. 5: Bronze Spear Head (NM62.288).

The black figure lekythos from 550-525 BC (fig 6) depicts two fighting warriors who face

each other side on, shields angled and resting on their left shoulder. Each employs an

overhead thrust with his spear. The target of an overhead attack such as this was to strike

above the opponents shield to the unprotected area of the neck or even the head. A

passage in the Iliad describing the Greek hero Ajax’s attack on a Trojan ally shows how

grizzly such an injury could be:

….sweeping in through the mass of the fighters,

struck him at close quarters through the brazen

cheeks of his helmet

and the helm crested with horse-hair was riven

about the spearhead

to the impact of the huge spear and the weight of

the hand behind it

and the brain ran from the wound along the spear

by the eye-hole, bleeding.55

The other option for attack with a spear was

underhand, aiming beneath the opponent’s shield to

the unprotected area of the groin:

His head already white and his beard grizzled,

Breathing out his valiant spirit in the dust,

Clutching his bloody genitals in his hands56

The victim in this case is an old man and it is worth

noting that all Greek citizens between the age of 18

and 60 could expect to be called up to fight. There

was no standing army as such but men were

expected to provide their own armour and weapons

and fight for their polis when required. The

exception, of course, was Sparta.

55

56

Fig. 6: Attic Black Figure Lekythos

with Fighting Warriors.

(NM49.07) 550-525 BC

Homer, Iliad, Book 17.293-298, translated by Richmond Lattimore (University of Chicago Press, 1951).

Tyrtaeus, fr.10.23-5.

18

The Spartans at this time were the most feared army in Greece, famous for their superior

skill in hoplite warfare, and for their discipline. Unlike other Greeks they were trained from

an early age in military skills. Just facing the Spartan army was enough to strike fear in

the hearts of the opposing army. Thucydides describes the superior discipline of the

Spartans as they advanced across the plain of Mantinaea (418 BC) slowly to the sound of

many flute players positioned in the ranks, in contrast to the violent and angry approach of

the Argives and their allies. This enabled the Spartans to advance steadily in step without

breaking their ranks, as usually happens when large armies are moving forward to join

battle.57

Spartan bravery is no where more legendary than in

the story of the 300 at the Battle of Thermopylae,

which took place ten years after the Battle of

Marathon during the Persian’s second invasion. A

Persian scout, sent to spy on the enemy, was

amazed to see the Spartans nonchalantly stripped

for exercise while others were combing their long

hair.

Compared to Athens, there is very little written

evidence in their own words about the Spartans and

the main archaeological evidence comes from the

site of the Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia where,

among other things, 100 000 small lead figurines

have been found, many in the shape of hoplite

soldiers. Left in the sanctuary as votive offerings,

they were cast in shallow, single sided molds.

Examples from the Nicholson Museum (fig 7) show

them carrying a large hoplon shield embossed with

Fig. 7: Lead Votive Figurines from

either a wheel or rosette pattern, wearing a high

theTemple of Artemis Orthia,

plumed helmet and carrying a spear. Most of them

Sparta (NM448.316.1-29)

face left with their shield held on the left side as you

550-525BC

would expect. However, the one facing right is

carrying his shield on the wrong arm, perhaps due to an error on the mold engravers part,

forgetting to reverse the figure.58 This figure is also different to the others in that he isn’t

standing in a characteristically wide leg stance.

Depending on what they could afford, since soldiers paid for their own equipment, many

hoplites would not have worn every piece of ‘hoplite panoply’ (greaves, shield,

breastplate, helmet, spear and sword) and there would have been many individual

variations. Not only would the full panoply have been incredibly heavy (about 30kg59) and

restrictive, it would have been incredibly hot (battles in the ancient world were fought in

summer) and uncomfortable. Describing the battle at Pylos during the Peloponnesian

War, Thucydides writes,

for most of the day, both sides held out, tired as they were with the fighting and

the thirst and the sun” 60

57

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, 5.70 translated by Rex Warner (Penguin, 1954).

A.J.B Wace, “The Lead Figurines” in R.M. Dawkins, The Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia at Sparta (London,

1929) p. 269

59 Victor Davis Hanson, The Western Way of War (New York, 1989) p. 56

60 Thuc. 4.35

58

19

As time went on, greaves and cuirass were often not worn. The change seems to be a

combination of the effectiveness of the phalanx formation and efficacy of the large shields.

This is supported by archaeological evidence that indicates that armour tended to get

lighter, less cumbersome, and less expensive.

Early on, the cuirass was made out of bronze, covered the front and back and had an

outward curve or bell shape to allow for movement as seen on the cup fragment (fig 3).

The earliest example of a cuirass was found in a grave at Argos (c.750BC) although the

workmanship suggests that this item had been in existence for some time.61 Later the

cuirass changed to a shorter model, often made from linen or leather and with hinged

strips of leather or metal hanging down to protect the groin while allowing maneuverability.

Fig, 8: Fragment of an Attic Hydria, Warriors Fighting. (NM97.68), 550-525 BC

Helmets also changed over time, becoming lighter and less restrictive. The bronze

Corinthian helmet seen on the black figure pottery in the

Nicholson’s collection (figs 1,3,5,6,8) was predominant from

700–500 BC. The Corinthian helmet covered most of the

soldier’s face and gave maximum protection. However, it only

allowed the wearer to look forward so, was only suitable for

fighting in close formation. It also had no opening for the ears

which made hearing difficult. The fragment from a hydria (fig

8) depicts two different styles of helmet crests. The one on the

left is fixed across the helmet while the other two are elevated

and the soldier in the middle has taken off his helmet to reveal

his long hair.

A small perfume oil jar from Rhodes (fig 9) in the Nicholson

Museum, dated to around 600BC, portrays a different type of

helmet and one that has only been found in artistic

61

Fig. 9: Warrior Head Vase

(NM47.01), 625-600 BC

Oswyn Murray, Early Greece (Great Britain, 1980), p. 123.

20

representations. This Ionian helmet has a semicircular forehead guard, hinged cheek

pieces and is more open than the Corinthian helmet, having no nose guard. The warrior

himself has a moustache, suggesting maturity.

Over time, the more open Pilos style of helmet (fig

10) was adopted. Usually made of metal or

leather, this bronze example from an Etruscan

tomb would have been padded inside but with no

cradle to provide a buffer against blows to the

head.

Therefore while there were changes to the armour

worn by hoplite soldiers over time, two items

remained consistent, the heavy shield and thrusting

spear. While every battle was unique, it is possible

to recreate a general sequence of events.

Usually an initial sacrifice for divination would be

made before setting off for battle, then just prior to

the armies’ engaging, another sacrifice, perhaps a

ram, would be offered to ensure a favourable

outcome as was done at the Battle of Marathon:

The dispositions made, and the preliminary

sacrifices promising success, the word was

given to move, and the Athenians advanced at

a run62

Fig. 10: Bronze Pylos (NM82.29)

4th Century BC

This mode of engagement was highly irregular and

surprised the Persians who did not quite believe

their eyes when they saw the Athenians running at them from a mile away. This part of

Herodotus’ story has been called into question by historians who believe that the weight of

the hoplite panoply is such that about 200m. is as much as any soldier could endure at a

run63 and still have energy left to hold up his weapons and do battle. Probably the hoplite

armies approached at a walk until they came within about 200m. of the enemy, at which

point they would lift up the pace into a jog.

The Commander-in-Chief gave the command to advance by beginning the paean, a

marching song or chant designed to keep the phalanx in step and psychologically

encourage the army while striking fear into the hearts of the enemy. The trumpeter

sounded the call and the soldiers joined in the song. As the armies drew close together in

battle the marching paean might be replaced by a war cry, eleleu.64

The classic phalanx formation was usually about 8 rows deep while the width varied

according to the size of the army. Men lined up by locality so they were fighting alongside

neighbours and relatives. At the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC, the Spartan army of 5000

would have been over 600 files wide.65 Given that the spears were about 8 feet long, only

the first couple of rows would have been able to have their spears over their shoulders and

62

Herod. 6.112

Hanson, op. cit., p. 144.

64 W. Kendrick Pritchett, The Greek State at War, Part 1 (University of California Press, 1971), p. 107.

65 Paul Cartledge, The Spartans: The World of the Warrior Heroes of Ancient Greece (New York, 2004), p.

67.

63

21

ready to attack. The rows behind would need to keep theirs raised to avoid harming their

fellow hoplites.

As to what happened next there has been much dispute, in particular as to how much the

push (othismos) was an actual push with hoplites bracing themselves with their shields

against the men in front or a metaphoric push to drive back the enemy with intensive

fighting66 which seems the more probable. What the sources do emphasize is the need

for each man to hold his place and play his part because it is only by doing so that the

army can fight as a cohesive unit:

Those who dare to remain in place at one another’s side

and advance together toward hand-in-hand combat and the fore-fighters

they die in lesser numbers, and they save the army behind them67

As each man stood in line their shield gave more protection to their left side and it was this

that caused armies to move to the right as Thucydides explains

because fear makes every man want to do his best to find protection for his

unarmed side in the shield of the man next to him on the right68

So the two armies met, and what was effective at the battle of Marathon against large

numbers of less well-armed troops became brutal when two hoplite armies met head on.

Those at the front ranks could see a little more through their enclosed helmets than the

men behind who would have had little idea of what was going on through the clamour and

the dust.69

Yet despite differences in weaponry and fighting technique, the human face of war is

universal. Thucydides description of the Athenian defeat during the Peloponnesian War

captures the anguish in the face of defeat and at the loss of lives that is common to all

wars:

The dead were unburied, and when any man recognized one of his friends lying

among them, he was filled with grief and fear; and the living who, whether sick

or wounded, were being left behind caused more pain than did the dead to

those who were left alive, and were more pitiable than the lost. Their prayers

and their lamentations made the rest feel impotent and helpless…..There was

also a profound sense of shame and deep feelings of self-reproach.70

The hoplite soldiers depicted on black figure pottery in the Nicholson Museum pre-date

the Battle of Marathon by up to half a century. Yet they can still provide evidence of the

armour and weapons used by the Athenians when they faced the Persian army for the first

time. While some elements might have been missing such as greaves and the Corinthian

style of helmet, the large round shield with its double grip, the long spear and the way it

was employed in an overhead thrust, remain the same.

66

Hans van Wees argues that pushing as a method of attack would not be sustainable throughout the battle

and that artistic representations show shields held at an angle, which wouldn’t be effective for pushing. “The

Development of the Hoplite Phalanx: Iconography and reality in the seventh century” in War and Violence in

Ancient Greece (The Classical Press of Wales, 2000), p. 131.

67 Tyrtaeus fr. 11.11-13

68 Thuc. 5.71.

69 Thuc. 7.44 Comparing the chaos and confusion of a night battle: In daylight…even then they cannot see

everything, and in fact no one knows much more than what is going on around himself.

70 Thuc. 7.75.

22

Cornelius Nepos: Life

of Miltiades

Translated with an historical commentary by: Garriock Duncan

INTRODUCTION: Those with some knowledge of

Marathon and the Persian Wars are probably somewhat

puzzled by my choice of Cornelius Nepos. Serious

students of these topics are not going to consult him.

They will concentrate on the Histories of Herodotus and the

relevant biographies by Plutarch. Nepos represents a

stage in the intellectual life of Rome towards the end of the

republican period and we must assume the subjects of his

(surviving) Lives were of interest to his contemporaries.

Some of his biographies are short and they illustrate that

the short answer is not just a modern phenomenon. If

Plutarch wrote a life of Miltiades, it has not survived. So let

us read the one by Cornelius Nepos.71

Bust of Miltiades

(i) The author: Cornelius Nepos is not widely known.72 Indeed, very few students of

Roman History or Latin Literature today would be familiar with him. He was born c. 110 BC

in Transpadane Gaul, from perhaps Pavia or Milan. 73 He knew the poet, Catullus, another

Transpadane, though some twenty five years Nepos’ junior, and they exchanged mutual

compliments for the other’s writings.74 There is no evidence of Nepos’ being in Rome

before 65 BC, the year in which he says Atticus came back from Greece (Atticus, 4.5).75

He probably made the acquaintance of Cicero trough Atticus. Nepos was possibly a

member of the literary salon hosted by Atticus. His relations with Cicero are problematic

because of Nepos’ distaste for Cicero’s philosophical writings, of which he (Cicero) was

inordinately proud.76 However, two books of Cicero’s letters were dedicated to Cornelius.

77 He spoke well of Mark Antony but showed no warmth for Octavian; he appears to have

been totally apolitical.78

Nepos was a prolific writer. He wrote a universal history; biographies of several notable

figures from Roman history, past and present; a geographical treatise; and even romantic

poetry.79 The Life of Miltiades survives from his last work, de viris illustribus (“on Famous

Men”), containing biographies of both Greeks and Romans and in many ways a precursor

71

For a brief discussion on the ancient sources for Marathon, see: Krentz, 2010, pp. 177-179; Sekunda, 2002, p. 94.

Full bibliographic details will be found in the list of References at the end of this article.

72

His first name (praenomen) is not known. For the pattern of Roman names, see: Duncan, 2009, pp. 18-19.

73

The date is calculated from his implication that he and Atticus, the friend of Cicero, were roughly aequales (i,e the

same age): Atticus, 19.1. For “Transpadane”, see: Duncan, 2010, pp. 21-22.

74

Horsfall,1989, p. 117.

75

Horsfall , 1989, p. 32, fr. 38, and p. 118, n. on fr. 38.

76

Cicero, Letters to Atticus, 16.5.5.

77

Horsfall, 1989, p. xvi.

78

Duff, 1953, pp. 309-310; Horsfall, 1989, p. xv.

79

Duff, 1953, p. 310; Horsfall, 1989, p. xvii

23

to Plutarch’s Parallel Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans.80 However, Nepos is

universally regarded as a very minor Latin writer.81

(ii) The translation: I would not normally have translated the Miltiades but rather just had

recourse to a translation. It is indicative of the neglect of Nepos, that the requisite shelves

of Fisher Library (Usyd) do not hold any (English) translation of Nepos.82 His style is

generally reminiscent of Caesar but occasionally he tries the grand Ciceronian periodic

sentence – alas, not well.83 I am very confident that no-one will ever need this translation

as a crib when studying the Latin text of the Miltiades. So, I have not sought to provide a

rigid literal translation. However, to give an indication of his grand style, I provide a very

precise translation of the first sentence of the Miltiades, following as far as English allows,

the word order of Nepos’ Latin.

For those who might want to try their hand at a piece of Nepotic Latin, I have included the

text of the first sentence of Nepos’ preface (Praefatio, 1.1 – sorry, no translation):

Non dubito fore plerosque, Attice, qui hoc genus scripturae leve et non satis

dignum summorum virorum personis iudicent, cum relatum legent quis

musicam docuerit Epaminondam, aut in eius virtutibus commemorari, saltasse

eum commode scienterque tibiis cantasse.

I have made use of a number of resources in preparing the translation and attached

comments. The text used is that of Winstedt (1904) and I have checked my translation

against that of Rolfe (1929). The notes are a collaborative effort . However, the main

contribution is the commentary of Nipperdey (1879).84

The Commentary: The notes are purposefully detailed. For, I am sure that most readers

will find the notes more useful than the text of Nepos. I have described the commentary

as historical; Herodotean is probably more accurate. The notes are principally a cross

reference to the edition of Strassler (2007).85 This is to be expected since Herodotus’

account is the standard. Indeed, it is rare to find an historian preferring Nepos’ version of

any episode in the career of Miltiades II to that of Herodotus. The one exception I have

come across is Green (1970).86

THE LIFE OF MILTIADES

Introductory Note: Unfortunately for Nepos, there are two Miltiades prominent in this period of Greek history. I am

going to follow the practice of Hignett and Jeffery and call them, Miltiades I, and Miltiades II. 87 Miltiades I was the

son of Cypselus; whereas, Miltiades II was the son of Miltiades I’s younger half brother, Cimon. Further confusion is

caused by the use of the same names in different generations, e.g. Miltiades II’s calling his own son, Cimon, after his

grandfather. Needless to say, Nepos confused them both. (ch.s 1 and 2).88

80

See: Geiger. 1985. There is another de viris illustribus surviving. This a late imperial work (4th century AD?) and

concentrates solely on Roman legendary and republican figures. For a translation, see: Sherman, Jr., 1973. 1973). The

authorship of Sextus Aurelius Victor is now rejected (Spawforth, 2003, p. 222b).

81

See: Duff, 1953, pp. 311-312; Horsfall, 1989, pp. xviii-xix.

82

The exception is Horsfall, 1989. However, he only provides a translation of the Cato and the Atticus.

83

On his style, see: Duff, 1953, p. 312; Horsfall, 1989, pp. xviii-xix.

84

I must thank one of my students, Monica Naish, for translating Nipperdey’s German text.

85

References to Herodotus are to: R B Strassler, ed., The Landmark Herodotus, Pantheon Books, 2007

86

One example. In his account of the failure of the Parian expedition pp. 44-45), Green’s text is based solely on Nepos

(7.3).

87

Hignett, 1952, Miltiades, q.v., index, p. 413b; Jeffrey, 1976, “Miltiades”, q.v., index, p. 268a.

88

References without name of author or title of text are to Nepos, Miltiades.. For a stemma of the family, see: Higbie,

2007, p. 791. A brief account of relationships within the family is given by Herodotus (Hdt., 6.34, 38,103). Herodotus

24

1(1) [Concerning] Miltiades II, son of Cimon89, the Athenian, since, because of the

antiquity of his family90, the renown of his ancestors and his own character91, he alone of

all his family particularly excelled and he was of that age, that not only could his fellow

citizens expect well of him but they could even take confidence that he would be the sort

of person that he was known to be, it happened that the Athenians wished to send

colonists to the Chersonese.92 (2)Since their number was great and many wished to take

part in the migration, envoys were chosen from among them and sent on a mission to

consult Apollo as to whom would be the best leader to use. For, at that time, the

Thracians were controlling the area and the issue would have to be resolved by arms.

(3)To the envoys, the Pythian priestess mentioned Miltiades I by name and stated that

they should take him with them. If they were to do this, the undertaking would turn out

well.93 (4)Relying on this response by the oracle, Miltiades I set out by sea with a chosen

band of followers.94 When he (i.e. Miltiades II) had reached Lemnos and was desiring to

bring the inhabitants of the island under the power of the Athenians, and had demanded

that they should do this of their own free will, the Lemnians mockingly replied that they

would only do this when after setting out from his home he had reached Lemnos with the

help of the Aquilo wind.95 For this wind, rising in the north, blows in the face of those

setting out from Athens. (5)Miltiades II, having no time to lose, continued the course he

was holding and arrived at the Chersonese.

2(1)After a short time there, when the forces of the barbarians had been scattered96 and

the whole region, the object of his quest, was under his control, Miltiades II fortified those

locations suitable for defensive positions. The large number of people he had brought

with him, he allocated to farming. He enriched them by frequent raids. (2)He was

has obviously been confused by the use of the same names in different generations of the family (see Higbie, 2007, pp.

787-788). The later writer, Marcellinus, also records details of the stemma of the Philaids. His information probably

only adds to the confusion (see: Fornara, 1977, n. 26, pp. 29-30 and n. 5, p. 30). For brief accounts of careers of the two

Miltiades, see: Boardman, 1999, pp. 64-265 (Miliades I), 265-266 (Miliades II).

89

Miltiades II married a Thracian women, Hegesipyle, and Cimon was their son (Plutarch [Plut.], Cimon, 4 (p. 144).

All references to Plutarch are to: Plutarch, The Rise and Fall of Athens, Penguin Classics, 1960.

90

The Philaids, the family to which both Miltiades belonged, ultimately claimed descent from Aeacus, son of Zeus

(Herodotus {Hdt], 6.35.1). The claim of descent from a divine being was standard among the Graeco-Roman elites; cf.

the claim by Julius Caesar that his family, the Julii Caesares were descended from Venus (Suetonius, The Deified

Julius, 6.1). Throughout the Miltiades, Nepos always uses the Latin forms of Greek names. Unfortunately, uniformity

is impossible. All Greek names will be spelled in the form familiar to English readers.

91

Nepos uses the Latin, modestia, for the Greek, sophrosune (“prudence’). See: Adkins, 1972, pp. 128, 132.

92

A chersonese (chersos [dry land] + nesos [island[) is the generic term in Greek for a peninsula (Liddell, 1964, q,v.,

p. 887a). The mention of the Thracians (1.2) make it obvious that the Thracian Chersonese, the modern Gallipoli

Peninsula, is meant. The status of the colonists is unclear. Both Nepos (1.1) and Herodotus (6.36.7) mention settlers

departing with Miltiades I. Nepos is silent about anyone returning with Miltiades II, whereas Herodotus mentions his

return with initially a convoy of five ships (6.42.2). Given the Athenian context, it is likely that they were kleruchoi

(Hornblower, 2003a, pp. 347b-348a). Although granted an allotment of land (kleros – Liddell, 19464, q.v., p. 436b) in

foreign territory, they always retained their Athenian citizenship and the right to return to Athens (cf. Hdt., 4.156).

93

Nepos account is significantly different to Herodotus’. It was the inhabitants of the Chersones, the Dolonci, who

consulted the Pythian priestess about a war with a neighbouring people, the Apsinthians (Hdt., 6.34.1). The answer was

that the first man to offer the envoys hospitality should be invited to become their leader (Hdt., 6.34.2). The envoys

reached Athens before an offer of hospitality was made by Miltiades I (Hdt., 6.35.2). Miltiades I consulted the Pythian

priestess and was told to accept their offer (Hdt., 6.35.3-36.1).

94

Since Nepos is supposedly writing of Miltiades II, he does not mention the significant reverse suffered by Miltiades I.

Miltiades I was captured by the Lampsacenes and only released because of the intervention of Croesus of Lydia (Hdt.,

6.37). Nepos seems unawares that Miltiades II had, actually, been sent out by the Pisistratids, who “treated him well”

(Hdt., 6.39.1).

95

It is Miltiades II, who gains Lemnos for Athens (Hdt., 137-140). Nepos talks of Miltiades II setting out from “home”,

when he obviously means Athens. He will continue this usage, since it later allows Miltiades II to trick the Lemnians.

(2.4).

96

The “barbarians’ are the Apsinthians (Hdt., 6.36.2)

25

supported in his endeavour no less by forethought than by luck. For, when thanks to the

bravery of his soldiers he had crushed the enemy army, he resolved matters with the

utmost fairness and decided to stay in that very place to live. 97 (3) Among his followers, he

enjoyed the position of a king, though he lacked the title,98 Miltiades II gained this position

no less by his authority than by his sense of fair play. He did not stint in showing favour to

the Athenians, from among whom he had set out. As a result, it came about that he

gained a permanent position of authority no less with the consent of those, who had

despatched him, than of those, with whom he has set out. (4)With the Chersonese

organized in this way, Miltiades II returned to Lemnos and demanded, according to the

agreement with them, the surrender of their city. The Lemnians had said that, when

Miltiades II arrived there after setting out from his home before a north wind, they would

surrender. He now lived in the Chersonese. (5)The Carians, then inhabiting Lemnos,

although matters had turned out unexpectedly, did not dare resist, overcome not by the

argument of their opponents but rather their good luck, and moved from the island. 99 With

equal good luck, Miltiades II brought the rest of the islands, called the Cyclades, under the

power of Athens.100

3(1)At the same time, Darius, King of the Persians, having brought an army over from Asia

into Europe, decided to make war on the Scythians. He had a bridge built across the river

Hister to bring over his forces. To safeguard the bridge in his absence, he appointed the

men of rank he had brought with him from Ionia and Aeolis. 101 To each of these men he

had given permanent rule of the cities they came from.102 (2)For he thought he could most

easily retain under his power the Greek speakers who lived in Asia, if he had handed the

cities over for safe keeping to his friends, who would have no hope of safety if he were

overthrown. Among the number, to whom this guardianship was entrusted, was Miltiades

II.103 (3)When frequent messengers brought news that Darius was conducting the

campaign badly and was being hard pressed by the Scythians, Miltiades II encouraged the

protectors of the bridge not to let slip the opportunity, presented by fate, of freeing

Greece.104 (4)If Darius, together with the forces he had with him, were to perish, not only

would Europe be safe, but also those of the Greek race, who lived in Asia, would be free

Hence the Chersonese now became his home rather than Athens. This justifies Miltiades I’s claim in 2.4.

Miltiades II, like his uncle before him, Miltiades I, was tyrant of the Chersonese. Tyrants were relatively common in

this era, eg the men of rank (3.1) and, of course, the {Pisistratids (8.1). Tyrant is a specific constitutional term and does

not mean tyrant, in our sense.

99

The inhabitants of Lemnos were not Carians but Pelasgians (Hdt., 6.137; Thuc., 4.109.4). Herodotus provides the

name of two cities on Lemnos – Hephaestia and Myrina. Hephaistia surrendered; Myrina did not and had to be put

under siege (6.140.2).

100

Nepos has badly confused Miltiades I and Miltiades II in 2. It was Miltiades II who gained control of Lemnos (Hdt.,

6.137ff).. The story is too long to recount here. Thus, it was Miltiades II who sailed from home to Lemnos with the

north wind (Hdt., 6.139.4-140.1) Lemnos was not one of the Cyclades (see map [Hdt., 445]. Lemnos is the un –named

island s.w from Imbros). The Cyclades did not come under Athenian control till the formation of the Delian League

(Thucydides [Thuc.], 1.98.2 – references are to: The Landmark Thucydides, ed. R B Strassler, The Free Press, 1996).

The reference refers to the Athenian attack on Naxos, the principal island in the Cyclades (see note 32 [French, 1971, p.

35]). The Cyclades are mentioned in the list of Athnian allies on the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (Thuc., 1.9.4).

101

The bridge had, in fact, been built by the Ionians (Hdt., 4.89), Darius’ original plan had been to have the broken

apart once his army crossed it. However, he was dissuaded of this course by Koes, son Exandros, of Mytilene, on the

grounds that this would trap his army in Scythia (Hdt., 4.98). Darius, then, ordered the Ionians to guard the bridge for

sixty days, and if he had not returned by then to dismantle the bridge (Hdt., 4.98).

102

I.e. these rulers were tyrants.

103