Anna Grigorevna Zherebtsova and Riga

advertisement

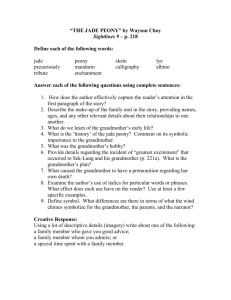

Anna Grigorevna Zherebtsova-Andreyeva and Riga My grandmother, Anna Grigorevna Zherebtsova-Andreyeva, arrived in Riga in 1922, with her two younger children, my uncle, Alexei Nikolayevich Andreyev (Lyosha, born 1905) and my mother, Kyriena Nikolayevna Andreyeva (Kyra, born 1908). My grandmother had been given leave of absence from her post as Professor of Singing at the Petrograd Conservatoire, and permission to travel, presumably because of the famine which followed the Russian Civil War. Marina’s grandparents, Aunt Ira and future mother were allowed to leave the Russian Republic for the same reason. My grandfather, Nikolai Vassil’evich Andreyev (my grandmother’s second husband) had died of Typhus in 1919. When they met he had been an Engineer Officer in the Baltic Fleet Imperial Yacht Standart. Family tradition relates that the Empress brought them together, and that he used to sing duets with her. On leaving the Navy he joined the Mariinsky Opera as a principal tenor, and had a flourishing career. In this photograph my grandparents are the couple on the right. The Empress is holding the book. One of her sons by her first marriage, Mikhail, had been killed in 1915. She had lost contact with the other, Serge, during the civil war. She settled down in Riga to earn a precarious living giving private music lessons. She and her younger children were effectively stateless, using Nansen Passports as travel and identity documents. Later on she said that she regretted having settled in Riga – she would, she felt, have been better appreciated in Paris or Berlin. The income from the fees she could charge was small, and she was in competition with other exiled Russian and Latvian singing teachers. During the summer holidays the pupils left for the beach at Jurmala, and the fees dried up. As well as giving the lessons she had to organise concerts for the pupils to show off their talents. In addition to being hard work the concerts carried a financial risk. As soon as they could my uncle and Kyra went out to work. Uncle Lyosha, who spoke good Latvian, obtained a job in the American Consulate (at that time all the western legations were boycotting Moscow). The American connections helped bring in pupils from the legation staff. He played for the local football team Riga Wanderers, and later for the national side. Kyra worked in a bank (where her typing speed earned her the title “the piano player”) and later anticipated Marina by giving English lessons. She became close friends with Marina’s Aunt Ira. However hurriedly my grandmother had left Russia, she appears to have been able to take her portrait. Here it is behind the grand piano topped with photographs of musical colleagues or composers, and Kyra in front. In 1927 my grandmother and Uncle Serge (Serozha) established contact. After the Civil War he had gone east along the Trans Siberian Railway and joined the Russian émigré population of Harbin in North China, working as a merchant. He presumably cultivated the friendship of the American Consul, obtained a transit visa, and arrived in Seattle in 1925. According to his entry in the passenger list he was en route to Paris. However he went to ground in Connecticut, New England, as an illegal immigrant. This had the unfortunate result that when two years later he was in touch with his mother he could not leave the USA to visit her. He was however able to send her much needed contributions of cash. Eventually he married a librarian at Yale and became a US citizen. A major subject of early correspondence was a platinum ring which my grandmother had brought out of Russia at considerable personal risk. She was very keen to send it to Serozha as soon as possible but official mail would have been out of the question. She had hoped that one of the prominent Russians of her acquaintance would have been able to take it, but she kept missing their departures. Eventually a pupil Mrs Macpherson, one of the Embassy wives, was returning to the USA and my grandmother entrusted the ring to her. A row then arose over whether the ring was genuine. We do not have Serozha’s letters, but he seems to have accused his mother of having changed the ring for a counterfeit. I suspect that he had taken it to a dealer who had offered him an inappropriate price. A contributory factor may have been that my grandmother had for some reason taken the ring out of its jeweller’s box and given it to Mrs Macpherson in a small bag. This may have been to make it easier to get through US Customs. After two or three letters peace was restored, just as my grandmother was in urgent need of a remittance from Serozha. A lot of correspondence concerned Russians who had settled in the USA, or friendly Americans who might be able to help Serozha establish himself. . This is the family at Christmas 1929. The unidentified man on the right may be Kyra’s future fiancée, an English refrigeration engineer called Bob King. She was clearly interested in acquiring citizenship, though not necessarily Latvian. In the summer of 1930 financial troubles in Germany led to a run on Latvian banks: 21 July 30 “Things are turning out badly for me, alas, much worse than last year. Then I had very many pupils, and now at once apprehension strikes, yesterday another (female) one disappeared, who is going to England in August, and at the very name of August I become horribly afraid. When Kyra is married I will be able to cut back some more, and then, if my health is good, I will do everything to put aside some of my earnings for an unlucky summer, although I hope there will at least as much work as last year, while now all my budget is flying away due to the proximity of Germany. The crisis is getting deeper. The banks are in panic. They say that that it came only through stupidity, rebounding from the closure of the Drishatsky(?) Bank, and was essentially without foundation. Now everyone is terrified, afraid to spend a half kopeck, God knows what will happen to all the ordinary people, as this, naturally, takes from everyone, while at the beginning of the summer everything was normal and quiet. Poor Kyra is terribly worn out, as she works till seven in the evening. Her bank is under English control, paying all clients in full, in these terrible days, when some other banks have closed, and now they have begun to pay out 5 percent of their deposits a week. Everyone is now rushing to the banks which continue to operate, and the staff are dead tired.” Things had not improved on 28 August 1930: “Now everyone is scared by this crisis. Everywhere in Latvia, with the exception of Kyra’s bank, all the banks are paying only 5% of everything and this has now created a panic even among the rich. This is such a misfortune. But of course it would be impossible to live if there was no hope, and I am trying hard not to lose it. Now there is something going on with the English, and I am worried that Kyra will marry an Englishman and will then be carried off from the ‘prosperity’ of this country. “ In the same letter she writes that she was very energetically putting together a synopsis of her memoirs, and that if she dared she would then write a book on singing, titled “A Handbook of Voice Training in Singing and Speech. She had already written the book in Petersburg, but there had been no time to publish it. However Lyosha was having a great time. In the same letter my grandmother writes: ‘I don’t know if I wrote to you that Lyosha has been on holiday for the whole of August, and went to Germany to play football against local teams. He returned sunburnt, and thank God well, as sometimes in winter he gets exhausted, and you can get hurt playing football if the game is rough. I would prefer him to give it up, though of course it is very interesting to travel free and get plenty of new impressions. He says that in all the football clubhouses there are pictures of Emperor Wilhelm and the Crown Prince, with Hindenburg underneath. What a loyal people, unlike the Russians! It impressed him after our cosy Riga – tremendous discipline – everywhere notices saying “forbidden” and “no loitering” – altogether like the forces. When his team was invited into the restaurant of a police team with which they had been playing they all wondered how they would be treated. In the end the Captain of the Germans cried to the waiter “Ober (ie Overcellerer), a beer”. They all exchanged glances, and then the Captain of the Wanderers said “Ober, twenty beers” – I can’t think how such a miserly country gets into crisis – it sometimes seems they simply pretend to be poor. Now Lyosha is off for five days to Estonia, to Reval, where there is a Baltic tournament at the moment, and he is playing in a combined team. Latvia will play Estonia and Lithuania and they begged him to go. His holiday ends on Thursday the 3rd of September and all returns to normal. I will be glad about that, as there are so many catastrophes involving trains and cars. Here at the moment a lot of aviators have been killed. I am glad all the time that you are not an airman – it is a terrible career.’ The engagement to an Englishman (Bob King) took place on 14th December 1930. In a letter to Serozha my Grandmother described him as “a very pleasant man who has been at our house for a long time and whom I have got to know very well by this time. .... His family are very upright and Blameless people, though not rich, living in London. He pleases Kyra, that is true, he is a remarkably cordial, pleasant and not over modern person. She would be exceptionally happy with him.” “This means that I will request Latvian citizenship for myself only, as Kyra will become in the autumn a British citizen, having an English, and not a Nansen passport, thank God. Although it will be sad for me to be separated from her, I am always worried about what would happen to her if I die.” My father, Colin, appeared on the scene in 1931 when his destroyer, HMS Versatile visited Riga with her flotilla. He had been writing to his mother twice a week since joining the Navy, but at this point there is a three week gap covering the Baltic deployment. When the correspondence resumes he is waxing lyrical about the sixteen year old daughter of a Swedish steel baron. However his meeting with my mother is recorded in an occasional diary which he was keeping encrypted in a low grade cipher. On June 10th he “met a most charming Russian girl called Kira Andreyeva.” The next day he met Bob King and “thought him an awful bounder”. He gave Kyra this photograph, inscribed “To Kyra from Colin, Riga 1931”. For further details of Colin’s career Google “Colin G W Donald”, or see http://holywellhousepublishing.co.uk/CGWDonald.html Kyra’s marriage to Bob King was supposed to take place in the autumn of 1931, when he would be promoted, receive a pay rise and have leave at the end of his posting to Riga. However things did not go according to plan. The refrigeration company was clearly in trouble, and in March 1932 it closed altogether and Bob King left for London to try to find another job. If things were favourable he would send for Kyra. My grandmother noted that she and Lyosha would have to move to a smaller flat, as my mother’s wages would no longer be available to help with the rent. In May 1932 Bob King was totally without work, and Kyra was playing tennis and saying she didn’t want to hear anything more about love and marriage. In October Bob King appeared to have found a job but it but the time was not right to ask for leave. This seems to have been the end of the matter. A frequent topic of correspondence from 1930 on was the doings of the Mdivani siblings. My grandfather’s mother had become friendly with their Georgian father, Prince Mdivani, who had been commanding a cavalry regiment in Sebastopol in the Crimea. In 1914 when the Prince was put in command of the Erevan campaign against the Turks his wife went with him. “There was a time when Nadezhda Pavlovna, mother of Nikolai Vassil’evich, did them some service. She dropped everything and went from Sevastopol to Tiflis to take over from Loulya Mdivani, who was leaving for the war .... the four Mdivani children all called her ‘Auntie’, and remembered her from that time.” The most frequently mentioned was Nina, who in the early 30’s was married to a businessman called Charles Hubberich. She was always meaning to help Lyosha and Kyra get established in Western Europe or the UK but somehow nothing ever transpired. Nina’s sister Rusya was married to a prominent artist named Sert, who had decorated the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. Their brother Serezha was tragically killed in 1936, to my grandmothers great sorrow. In the same letter she mourned the death of Alexander Glazunov, Director of the Petersburg Conservatoire from 1905 to 1928 – “a major part of my musical career has departed with him and finished”. Not long afterwards Nina married Denis, the youngest son of Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle (borrowing Randolph Hearst’s castle in Wales for the purpose) – my grandmother wrote “it’s like being in a film”. The other brother, Alexis, was married to Barbara Hutton from 1933 to 1935. After the WWII we were in fairly regular touch with Nina, until her death in London in 1987. The wake after the funeral was like a meeting of the Georgian Government in exile. The 1929 Christmas photo was used as an ad hoc postcard dated July 1932, the address then being Vasingtona, lauk. 3 dz. 1 (3 Washington Square, Flat 1). This is what it looked like then, with the flat windows marked with XXX. And here are the same three windows in June 2013: The Washington Square connection may not have been simple fortuitous, as there had been a US Embassy building round the corner. This letter from the spring of 1934 gives a valuable idea of the family routine, but also the amount of work involved in putting on a student’s concert with considerable doubt whether the student will pay, and the cost and anxiety of renewing essential residence permits. 1 March (1934) My dear Serozha, There has not been a letter from you for a long time – I imagine that that is because you went to New York. How were things there? Did you manage to set anything up? It says in the papers that that you have had terrible snow. I hope that you have not caught cold. I think that you are already out of the habit of coping with frost and snow. Here on the other hand it has been plus three degrees all this time, and all the snow has melted, to the distress of the local skiers. Kira has taught herself all about this sport - her friends from the bank gave her skis. Lyosha gave her his old sports trousers, which she altered to fit her, but here winter is over. However today it is freezing again. Three days ago was the concert by my pupil Mil’da Langenfeld. She distinguished herself, and everyone praised her – the critics and the public. She was enraptured about it of course. I am only interested in whether she pays me for the supplementary lessons, which she had for the whole of this month – instead of two hours a week she had eight to ten hours from me. Apart from that I gave her the accompanist for the lessons as a gift. All this was necessary to get her ready. It will now be interesting whether it comes into her head, that she needs to pay. I was embarrassed to speak to her about it, and am afraid she may leave me, as you did with your professor. And she is very, very rich. As a matter of fact, with us and you yourself there persists an unnecessary gentility, it is always awkward for me, when they haggle with me, or cheat me, to speak of money. As usual I have been very busy all this time: in the morning, before the pupils arrive I go to the prefecture of the district to petition on behalf of Kyra and myself not to have to pay a heavy fee for a passport, and the right to work without a work permit. I have succeeded, thank God – I paid for only a rubber stamp on an endless quantity of papers, but this is total nonsense. It is laughable that I had to take two witnesses to the police, to testify that I have not hidden money in a bank somewhere, and that I had no property. I took the landlord of our flat, who has seen that, for the two years we have lived with him, that we have not fuelled the stove, and cook on a (kerosene) primus, and Frau Spure, my old servant – my principal helper – who knows how badly, and how irregularly, the students now pay. A protocol was drawn up, which they both signed – such nonsense! Here, on the edge of the world, there are no rich Russian emigrants – any Russians, who are rich, are not emigrants, but local residents and landowners, from whom much has been confiscated, chiefly castles and estates, but they still retain a lot. I am very sorry about the King of Belgium (killed in a climbing accident in Eastern Belgium) – what a stupid death – what a mistake to let their King go alone. All the time such things are happening, that now it is frightening to open a newspaper. I hope that when you return you will write to me at once, Serozhenka, it is so boring without your letters. The postman comes at 10 am, and I am almost always waiting for him. I want to ask you to write to me sometime about how your life goes - it interests me so, and it will be the same for you, to know how we live here. At 8 am Frau Spure calls the children. They first get up and drink coffee at about 9 am, and then go to work. Then I get up and prepare lunch and dinner. At 10 am my first pupil comes. At 1.30 pm Lyosha comes home, sings a little with me, and we have lunch together. At 2.30 he goes and the second group of students start lessons, and on those days when there are a lot of them, I am very happy. Unfortunately three disappeared after January for different reasons, though I think that those reasons were only a pretence, and they simply had no money to pay. At about 6 pm Lyosha and Kyra return, if they have not got business in town – Lyosha practices at the Studio, and Kyra gives English lessons three times a week. At 7 pm or 7.30 I am free of my pupils, we have dinner, and then mostly stay at home with the radio, while Kyra and I mend something or sew. Sometimes we go to a concert or the opera, or, if we have tickets or konramarks, the cinema. Once they abolished konramarks, and we were very indignant. At 11.30 we almost always go to bed, but after a concert by my pupils, with all the nervousness and worry, I lie down at about 9 pm, and don’t normally give singing lessons to Lyosha and Kyra, who also now sings. This provides beauty in her life, so that it is not just that of a working girl. But I thank God for her job, as it gives her the means to live. Kyra and Lyosha pay for the flat, and I feed them. Have you seen and heard Orlov? * I don’t know whether he will appear in Riga in the spring, or only in the autumn. What are they writing about him this year? I kiss you warmly my dear. God keep you. The children embrace you, and we all together send our greetings to dear Frances. Your Mama. *Nikolai Andreyevich Orlov (1892 – 1964) was a Russian pianist who graduated from the Moscow Conservatoire in 1910. He worked as a teacher in Moscow 1913 – 1921 and then moved to the West. He made several successful concert tours round the world and settled in the United Kingdom in 1948. Worse was to follow. The Soviet Union had settled its debts to the western powers and been recognised, so embassies and consulates which had been located in Riga were about to move to Moscow. 9 December 1934 Vasingtona, lauk. 3 dz.1 Prof A Zerebcova-Andrejeva Riga, Latvija My Dear Serozhen’ka,, By my estimation you should receive this letter in time for Christmas. We send all best wishes to you and Frances for the Festival and coming New Year, wishing you both happiness and good fortune in all things. We deserve to have a festival sometime in our street! But all around we only hear of sickness and death, and terrible operations, so we must thank God that we have some unpleasantness, but not illness and death. Then nothing is lost and hope still remains over misfortune. A great misfortune has suddenly struck us – Lyosha has lost his job at the American Consulate. It will gradually close and move to Moscow. They dismiss the Russians first as the Diplomatic Corps has business with Russians only with the Soviets, following the recognition of Soviet Russia and the settling of debts. Lyosha had already received a paper last January (34),warning all embassies and consulates that in the near future all consular functions would move to Moscow. The Latvian Pro Embassy, which will be so drastically cut, will only have two people to issue Latvian visas, but this will be drawn out over a year. It is hurtful that they have paid Lyosha off before the Christmas holidays, and given him only two weeks salary in advance. He wanted to petition for another two weeks salary, for the month after leaving the job. All this misfortune comes from the death of Carlton, the former Consul. He would have protected Lyosha to the end, so that up to the end of January, when the Consulate is to move, he would have remained in the office and closed down the establishment. This was long expected, but we were optimistic, and thought that if it happened it would not be so quick. At first I was very shaken, but took myself in hand, and although very anxious devoted myself to work and did not let this upset interfere with any lessons – to be busy is ones salvation . We both scolded Lyosha for hiding the paper from Kyra and myself, and pointed out that there was a lot he could do at the moment to prepare for the loss of salary, which though not large he got regularly all the year round. Now we must build on his singing. He has a delightful voice, talent and style, and has appeared successfully six times to date. He needs only finish, hard work and training as there is a lot of competition; in spite of the quality of his voice and talent there are the problems of connections, nationality and passport. Why are we still only Nansen passport holders? He will be on the radio and will sing in January – it will pay a little, but the work, to sing familiar things for twenty minutes, costs little too. He has decided to look for all kinds of work to contribute a little to his keep. Yes, it is very difficult without a permanent position, every blow throws you of balance, and once lost it is difficult to find it again. Thank God he did not come to you in America, where he would be sitting with you with no job – at least here he can study singing. He is very depressed, and in spite of light heartedness and a certain flippancy he fears the future, and I hope that he is able to get back on his feet. It will take much effort, enthusiasm and perseverance. He needs to acquire a repertoire, and study more in Latvian, Italian and Russian. (The rest is up to God!). Your last letter was dated 9 November, and I received it on 22 November. I hope that you are both healthy and that all is well with you. I kiss you warmly and embrace you. The children both greet you. Don’t write any more to Lyosha about the Consulate. On 1 April 1935 my grandmother wrote: “My concert with my pupil Bara was on the 20th March. I prepared her successfully, the concert went well, and the reviews were good, but it gave me a lot of stress and worry. Now I am getting Lyosha ready for a celebration of the composer Borodin. He will sing one very difficult aria of Prince Vladimir from the opera Prince Igor, and a very difficult duet, but it is going well. I am worried at the moment – he has an incredibly swollen gland, and they say it must be removed. It makes me very uneasy and frightened. I am still coaching Mary Saks – she sometimes came to me for study in Petersburg, and married the Latvian Professor of Singing Saks – a very influential person. Now she is marrying again and came to me to prepare herself. Sometimes Shaliapin sent her to me in Petersburg. God grant that it goes well, but it is a great responsibility” Professor Saks laid the first wreath at my grandmother’s funeral in 1944. “Here is some news – they want to register all private music teachers, and of course I am now a private professor. I wrote out the application, and went to hand it in at the Ministry of Culture with Lyosha who knows Latvian. I don’t know the result yet but they tell me that they can’t prohibit such a well known specialist, but they have prevented many from teaching. Have you read about the 5000 former aristocrats and gentry who were deported from Petersburg in a three day period. It is ghastly.” There was more mixed news in a letter approximately dated September 1935 “Kyra and Lyosha have finished their holidays, and both returned home to work black from sunbathing, and at once the weather changed and it became cold and windy. I even got out of Riga a few times, three times with Kyra to Oger to the sanatorium, and five times to the seaside. Last year it was only once, so all this is progress. In myself I feel not at all bad, though I feel it is a shame that I never go anywhere for a rest. Here even the poor go away for a week but I cannot get properly organised, and here at home is comfort, and on the whole I live in town conveniently. All of a sudden there is a genuine worry about the flat. The landlord has sold the house without telling anyone, and now they are threatening to turn us out because the new owner wants to live here himself. This only came ten days ago, and now the teaching season is starting, and I cannot think where we will go if they evict us. Everything is so complicated with lessons, and landlords won’t allow singing everywhere. But God grant something will be arranged while we are waiting, and next Sunday I will put up a notice in my studio asking for people to take on more lessons, and that previous pupils return and enrol again.” There is no record of any enforced change of address, so things seem to have settled down. Lyosha managed to get a lot of work singing in the Opera and on the radio at Libau (Liepaya). However his efforts to join the Riga Opera were frustrated by a nationalist Latvianisation plan, and although he spoke excellent Latvian and had played in the Latvian National football team they would not take him on. In the end he became a tenor with the Russian Don Cossacks Chorus, which took him away on tour. Meanwhile Kyra had used her meagre savings to go on holiday to London in the summer of 1936. She and Colin had been writing to each other since their meeting in 1931. He was at the Staff College at Greenwich so they were able to meet. My grandmother wrote to Colin approving their engagement, in German, as he was a qualified interpreter. 22 October 36 My dear Colin, My Kyra has spoken to me of you so often that it seems to me that I have already known and loved you for a long time. Your letter touched me deeply, and I am happy that fate ordained that you should encounter each other in this life, you suit each other so well in all things! Kyra was always a good child, and in difficult times she was always not only a comfort but also a moral support to me. I am convinced, dear Colin, that you will be happy with her at all times and in all circumstances. May God bless you both, and may He also grant that circumstances allow me to come to the wedding and get to know you and your dear parents, that is my greatest wish and dream. With greetings from my heart Anna Yerebtzoff-Andreeffa They were married in December 1936, as he was about to graduate and take up an appointment on the staff of CinC West Indies, based in Bermuda. Serge was at last able to meet them in June 1937. In fact Kyra’s sojourn in Bermuda was not continuous. Every year the West Indies flag ship, HMS York, went on a three month cruise, and rather than leave her on her own in rented accommodation it was cheaper to ship her back to UK for the duration. In 1937 she visited Latvia and was able to take my grandmother and Lyosha on holiday for two weeks in a hotel. By 14th July my grandmother had moved to a new flat: Exportas iela 4 Flat 9(Export Street, by the river, 1937 – 1939) In a letter dated 19th September 1937 my grandmother reports that life was becoming very difficult for non Latvian artists. “They have put up a notice in the National Opera that on-stage conversations between the artistes that are not in Latvian will be fined 1000 Lat ($200). Lyosha knows Latvian well, but all the same he is a foreigner, and they have drawn things out for two weeks altogether plaguing him. I haven’t left the place myself, waiting all the time for a phone call or letter so as to find out something . Now I am frightened , as Lyosha writes that he is coming home and that I should expect him tomorrow, as under a proposal that they should move to an ethnic Latvian National Opera, it has been decided that foreigners (Russians) should not take part....... I have started my involvement with the Russian singers’ organisation “Bayan”, which I was invited to join. It will meet in the evenings. Although it pays almost nothing, from the advertisement it guarantees a decent funeral with choir and speeches, and the attention of the Society.” The Society also had a medical fund – a great advantage as my grandmother never had money for doctor’s fees. The Bayan Choral Society organised concerts, which are listed in a history covering its 75 years, with this picture of my grandmother in her studio. My parents returned to the UK in 1939. My father joined the Battleship HMS Iron Duke (the Grand Fleet flagship at Jutland but now a boys’ training ship based in Portsmouth). They took a small house in Southsea, and were able to arrange a visit for my grandmother and Lyosha to England in the summer. The families, including my other grandmother, my Aunt Barbara and cousins Rosamund and Angela met up on Dartmoor. By this time my grandmother had moved to a smart address, Elizabetes iela 19 (19 Elizabeth Street), in the Art Nouveau district of Riga, though I am not clear how she could afford it. On her return to Riga she received the welcome news that Kyra was expecting (me). (Actually the flat was a “house in multiple occupation, with a Baltic German landlady and two or three tenants). Lyosha rejoined the Chorus, which was based in a small watering place on the Baltic coast of Germany called Herringsdorf, preparing for a tour. Fortunately the management was alive to the situation and the Chorus sailed to North America via Norway and toured there. This left my grandmother all alone. After the war started letters could be sent in French via Sweden. When the Soviets occupied Latvia in the autumn of 1939 Elizabeth Street became Kirov Street for a while. My grandmother was on the second list for deportation to Siberia in 1941, along with Marina’s family, but was saved by Operation Barbarossa. The last letter is dated 18th May 1941. It was also possible to exchange brief telegrams, the last being 23 June 1941, just before the Germans arrived. After the Germans occupied Latvia short letters in German could be sent via the Red Cross, taking as much as six months for a round trip. However she was still able to send a letter to Serozha (or Lyosha) in September 1941, as the USA and Germany were not yet at war. She briefly described the activities of the “Cheka” (as Russian émigrés called the KGB), the executions and deportations – things she would not have been able to mention in earlier letters due to Soviet censorship. September 25 1941 By a miracle I can send you a letter – Andrew came and promised to send the letter. I was greatly worried that you my dear children are thinking about my fate, but I did not know how to let you know that I am alive and that everything turned out well. I escaped terrible danger not only because I escaped the bombardment of the city, but also all last year was bad ..... When the Reds came and arrests started I should have felt unsafe because I had not returned to Russia. When they let me out 19 years ago from Petersburg I gave a promise to return to the conservatory of music and many were worrying about what would happen to me. I could not write about it ... I was greatly cheered by your note where you stated that you and Nina are trying to get me out, and I entertained some faint hope. I never received your money nor letter which you cabled as having sent on May 4th .... Everyone was amazed that I got the first remittances. ... Life was all a nightmare, I called it a “tragic nonsense”; then they started to send people away inside the Soviet Union; they would raid apartments at night and load people into freight cars; old people, one aged 85; and young children alike. On the night from 13th to 14th June, Cheka agents came to fetch our landlord and his wife, and I heard the noise, so came out, and the secret police agent threatened me with a gun, so I got right back into my room ..... I had many students in the winter, right now I have ten and I want to make an advertisement ..... Hope sincerely to live through to the end of this war. I received Kyra’s cable of the tenth of June, in which she states that my grandson began to walk. I sent her a blessing by cable. .... Write to me care of Andrew’s mother, perhaps I shall get it. Serge did not understand the situation because he did not realize what sort of people are the Reds – he never lived under them. .... Please give my regards to Nina and to Frances...... . The Red cross letters were originated by my mother with a short 25 – 30 word message, and my grandmother wrote her reply on the back. The average one way transit time was five months, though one letter took ten. Sometimes letters reached my grandmother in groups of two or three. On 16th December 1942 my mother wrote that Lyosha had married a nice girl the previous September. On 27th July my grandmother asked “what is his wife’s name? Was Nina (Mdivani) at the wedding?” . My mother never answered those questions, but my grandmother did eventually hear from Lyosha directly by November 1943, so I hope she got an answer. Lyosha’s bride was Zonya Porter, and they met on Ellis Island, at a concert involving the Don Cossacks’ Chorus and the Sperry Gyroscope Symphony Orchestra. Zonya was an accomplished violinist and the leader of the orchestra. She had previously been Miss Television at the Pennsylvania State Fair of 1938, and stand in for Judy Garland for the film “It happened in New York” – Miss Garland had stayed in Holywood. Lyosha and a number of other members of the Chorus enlisted in the United States Army, but fortunately Lyosha was drafted to be Chaplain’s Assistant at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Here he is with Nina on his left, and Denis Conan Doyle opposite. My grandmother died in the spring 1944. My mother told me that she had died in her sleep and had been found by her maid in the morning. She was buried in the Pokrovskiy (Protecting Veil) Cemetery. and she, and the grave, were largely forgotten. However her memory, and the grave, were restored in 2004, under the auspices of the Russian Cultural Institute of Latvia. The article below is not entirely correct, and I am halfway through translating my grandmother’s memoir of her meetings with Rimsky-Korsakov, on which it is partially based. Anna Grigorevna Zherebtsova-Andreyeva (1868 – 1944) “The funeral was magnificent” – the old Rigan, jurist and boundary expert B V Plyoukhanov told me – they came in crowds – “pupils, staff of the Latvian Conservatoire, colleagues, admirers of her talent .... and that is all that now remains...” And indeed, the sight of the tomb of the famous singer, professor of the Petersburg and Latvian Conservatoires Anna Grigorevna Zherebtsova-Andreyeva at the end of the 1980s and beginning of the 1990s made a depressing impression, appearing to me personally as a symbol typical of the state of the Pokrov Cemetery. Almost opposite the memorial to the Russian soldiers who fell in the years of the First World War, yawns a black pit, a rectangular well with crumbling brickwork and concrete. The funeral had taken place in 1944. “Sic transit gloria mundi” I think to myself every time that I set out to lead a tour or simply go by myself to this place of remembrance of the celebrated of Petersburg. Sadly we Rigans know little of these creative personalities, borne to Latvia on the wave of post revolutionary emigration. And it was far from simple to trace sources of this Russian opera singer so neglected in the post war period. A G Zherebtsova-Andreyeva was born in Grodno on 25 September 1868. In 1892 she graduated from the Petersburg Conservatoire in the class of N A Iretskaya (who also taught her own daughter Natalia Iretskaya, who died in Riga and was buried beside Zherebtsova Andreyeva beneath a black marble tomb.) Already in 1891 the young singer – a mezzo soprano - had made her first appearance in Conservatoire concerts organised by N A Rimsky-Korsakov. The vocalist herself retained interesting memories of meeting the eminent scholar, and his role in her creative life. A memoir “My encounters with N A Rimsky-Korsakov” appeared in the magazine “Russian Song in Riga” in 1938. She recreates images of the celebrated fashioners of musical taste, and the background in which the development of the vocalist’s personality took place. “Rimsky-Korsakov wants you to sing the role of Lel’ in ‘Snowmaiden’ “ my professor turned to me one day when I came into the Conservatory class room, Anna Grigorevna recalls. I was both delighted and fearful – I had often seen the tall figure and severe face of Rimsky-Korsakov at the Conservatoire, in the corridor and at musical evenings, but I had only recently become acquainted with him when, at a soiree chez L E Karmalina, they performed the romances of Glinka and Dagomuisky, which were exceptionally appreciated in Balakirev’s circle. Balakirev himself took part. They pressed me to sing the third song of Lel’, but I had no idea that this would produce such a result. In spring Rimsky-Korsakov came into my professor’s class room and asked me to agree to perform the solo part in a cantata for soloist, choir and orchestra, which had been written by his pupil Bravchinsky. I began hurriedly to learn my part – when the time came for my aria and I sang it, to my horror I heard in the orchestra accompaniment a great deal that was not in the piano reduction. As a true pupil of his great teacher, Bravchinsky had orchestrated his cantata richly – I did not recognise this accompaniment – I was certain that I had long since lost the beat and that I would be stopped at once and sent away in shame, but I still continued and with despair in my heart sang on. It turned out that all went well. Bravchinsky thanked me profusely, and Rimsky-Korsakov himself laughed for a long time when I told him about my experience. Frequently gazing at the eminent composer I thought, in spite of everything, what a remarkable man! During the next season, not long before my graduation, after I had sung at a soiree at the Karmalin’s, Rimsky-Korsakov introduced me to an old lady with lively eyes – it was the sister of M I Glinka, L I Shestakova. The day after our conversation Lyudmila Ivanovna sent me a little book of her memories of M I Glinka with the inscription “To the resounding skylark A G Zherebtsova from the sister of Glinka” (the evening before I had sung her Glinka’s delightful song “Skylark”). In the spring I went to Germany where I appeared over the whole winter in various cities. While I was in Dresden I received a letter from Rimsky-Korsakov, inviting me to take part in his concert series in Odessa. (1) Rimsky-Korsakov and his wife met me at the station in Odessa. ... The concerts went brilliantly, and he was honoured both at and outside them. We lived some hotel or other. They also took me to see the celebrated painter N Kuznetsov, where we inspected his studio, full of his beautiful pictures. Nikolai Andreyevich was in good spirits and at dinner got me to tell him about musical life in Germany. ... After Odessa I went abroad again, this time to Holland. Rimsky-Korsakov and his wife saw me off, and warmly invited me to be with them on my return to Russia. Their sincerity moved me deeply. ... I accepted their invitation and was often with them at their soirees at 28 Zagorodny Prospekt. It was possible to meet Glazunov, Lyadov, Chepernin, and all the prominent musicians, friends of RimskyKorsakov, but particularly M P Belyaev, founder of the publishers of Russian composers, in Leipzig and organiser of Russian symphonic concerts, who asked me to take part in them. I was struck by the figure of B Stasov, the famous critic-enthusiast, pronouncing in a thunderous voice approval or disapproval of music heard for the first time. For the first time I committed notes of many of these soirees to writing, as they would always be of interest. From the notes, I sang and there dedicated myself for the first time to romances – “Poesy” by Arensky, accompanied by the composer, “Angel” by Rimsky-Korsakov, and “You are not grieving” by the young composer Shcherbachev. After the death of the composer in 1908 Anna Grigorevna dedicated the largest part of the programme of a concert to romances by Rimsky-Korsakov. In the middle was the romance dedicated to his wife N N Pourgol’d, which she particularly loved “The rainy day is over” with words by Pushkin. After the concert, the singer recalls, “Nadezhda Nikolaevna came to me in the dressing room and embraced me, and we both wept.” On graduating from the Conservatoire, as is clear from her memoir, A G Zherebtsova went to Germany, where she successfully performed in concerts, preferring to take part in symphonic soirees. The singer became a member of the Petersburg Chamber Society. She received the high appreciation of A G Rubinstein. In her repertoire the singer gave pride of place to the works of contemporary composers. Many vocal novelties made their first appearance in Russia in her performances, among them the compositions of C Debussy, M Ravel, R Strauss (2). She too gave the first performances of a number of works by I F Stravinsky, S S Prokofiev, and the romances of Arensky, Shcherbachev. In 1903 (or according to other sources in 1907) A G Zherebtsova became a teacher, and from 1913 to 1922, a Professor of the Petersburg Conservatoire. As a singing teacher she followed in the tradition of the school of N A Iretskaya. From that time pupils of Professor A G Zherebtsova-Andreyeva appeared on the stage of the Mariinsky Theatre and in the provinces, and were among the soloists touring with the Riga Former Imperial Court Chapel Choir. In Latvia the Professor taught such singers as Zh Sladkarova-Yakovleva (in her day she appeared in the “Shalyapin Spectacle” in Berlin and in the chorus of the Latvian National Opera) and the artist of the Liepaja Opera M Skouchin’. At concerts in the Conservatoire her pupils performed the works of A P Borodin, N A RimskyKorsakov and their successors. During the last months of her life Anna Grigorevna still gave private singing lessons. Some open questions remain regarding the Professor’s connections and acquaintances in Riga*. Naturally, working in the Latvian Conservatoire she would interact with many colleagues, and would clearly have known some of the soloists, musicians of the National Opera, and Russian colleagues with whom she associated or corresponded – but all of this must be left for later. Her grave (sector Zh, No 2) has been put in good order and restored, thanks to the increase in Russian public spirit, specifically the enthusiast Svetlana Vidiakina. A memorial plaque is still needed. But who among old and contemporary Rigans, who appreciate classical music and opera, are aware that under this brick covering rests the “Resounding Skylark” , Professor of Singing A G ZherebtsovaAndreyeva, participant in the Silver Age of Russian Culture, half forgotten in Riga, but worthy of an entry on the Golden Book of St Petersburg. S. Zhouravlev * A G Zherebtsova-Andreyeva collaborated closely with the Russian Choral Society Bayan. Information on it is to be found in a small book, commemorating 75 Years of the Society. In this publication there is a photograph of Anna Grigorevna at home. For further information see “Russian Song in Riga” a magazine article under the editorship of A Perov, Riga, published by “Bayan” 1939. Her funeral service took in the Pokrovsky Church, the ceremony being conducted by Grigorii Ponomarev. The first wreath was laid on the grave by the Professor of Singing at the Latvian Conservatory, P Saks. There is no evidence that she ever worked at the Latvian Conservatoire (below), though she did hire the hall for concerts by her students. FD (1) Actually the German tour was organised by Anton Rubinstein, and included a concert to inaugurate the Bechstein Hall in Berlin. He had resigned from the Directorship of the St Petersburg Conservatoire over Imperial demands that admittance, and later annual prizes, should be awarded along racial quotas instead of purely by merit (which would effectively disadvantage Jews.). In May 1913 my grandmother made her London debut in a recital in the Bechstein (now Wigmore) Hall. The programme included notices from the German press from 1891, such as “Yesterday Rubinstein proved himself to be not only a master of inexhaustible originality, but also a discoverer of new talent. A young Russian, almost a child, Anna von Jerebtsoff, made her first appearance in public. Rubinstein must surely appreciate the young girl very highly, for he accompanied her himself. In two poetic songs by Rubinstein the young novice won a storm of applause by the charm of her expression and her delicate and penetrating rendering of the coloratura passages. (Dresdener Zeitung) (2) In January 1914 my grandmother was back in England, giving recitals in the Bechstein Hall and in the Town Hall, Barrow in Furness. In the notes for the Barrow concert we read “Although excelling as a lieder singer, she is also a distinguished interpreter of oratorio, operatic aria, etc., and Dr Richard Strauss was recently so delighted with her interpretation of some of his most difficult and lesser known songs, as well as excerpts from ‘Ariadne auf Naxos’ and ‘Rosenkavalier’ that he has himself offered to appear in conjunction with the famous singer at St Petersburg in the near future. Those who know with what care the celebrated composer selects artist to interpret his compositions will readily appreciate what such a complement means.” Another “what might have been of 1914!