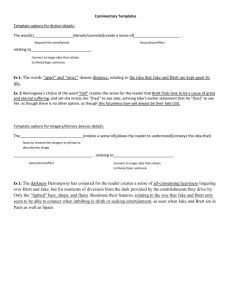

Kate Liu Exhaustion But Not Death: The Human Constructions in

advertisement

Kate Liu Exhaustion But Not Death: The Human Constructions in The Floating Opera and The End of the Road The Floating Opera and The End of the Road, John Barth's first "twin" novels, have been regarded by many critics as "existential" in content and "realistic" in style, and therefore "representative of the author's apprenticeship before he turned to more avant garde ...later novels" (e.g. Glaser-W™hrer 207; Stark 118; Harris 11). Even Barth himself said that the two novels "were ... done in a manner of conventional realism"(Cooper 6) Since 1970, however, some critics have started to find in these two novels greater connections with Barth's later novels in terms of artistic self-reflexivity. Thomas LeClair, for instance, shows how in The Floating Opera Barth establishes "the aesthetic rationale of his later fiction" (711). To Hiedi Ziegler, too, Barth in these two novels "take[s] the existential novel in order to create a self-reflexive problem" (25). The narrator- protagonist's artistic constructions in the novels, nevertheless, are seen negatively by most critics. To LeClair and Charles Harris, Todd Andrews' narrative as a floating opera is "irresponsible," "amoral" and a falsification of reality (LeClair 723; Harris 11). To Ziegler, Jake Horner's narration in The End of the Road "reaches the point of possible paralysis" (30). What these critics fail to see is the fact that, to Barth, narrative distortion is inevitable and "exhaustion" is also "replenishment." It is true that both Todd's and Jake's narrative constructions are not without contradictions or distortions, but to Barth, distortion is inevitable in our understanding of this labyrinthine life and fiction is "a kind of true representation of the distortion we all make of life" (Prince 54; emphasis mine). What makes Todd's and Jake's narrative constructions "truthful" and thus different from their previous rationalizations is exactly their awareness of the arbitrariness and incompleteness of their constructions in face of the multifarious and fluid reality. Moreover, their writings serve as a way out of a dead end in their life, allowing them to act and to make sense of life, past and future, in way more authentic than before. What Barth achieves through the two narrators, in other words, is "exhaustion" in his sense of the word: both stylistically and thematically, "he confronts an intellectual dead end and employs it against itself to achieve new human work" (Barth The Friday Book 69-70). In this paper, therefore, I would argue that both Todd Andrews's and Jake Horner's selfreflexive narrative, as a "truthful" distortion of life, represents an "exhaustion" that leads to replenishment but not a dead end. The exhaustion Todd faces in The Floating Opera on the day he plans to end his life is that of his rational control over his existence. Before his attempt at committing suicide, Todd has been trying to use his rationality to master, or to escape from, the "fact" of his life: his weak heart. His heart is "weak" both physically and emotionally. On the one hand, Todd's heart disease makes him constantly threatened by an immediate death, from which he "rents" his life day by day (49). On the other hand, Todd is also emotionally lacking, partly because of his lonely childhood (surrounded merely by his inattentive father and a succession of indifferent maids and housekeepers), and partly because of his self-detaching rationality. Closely related to the problems of his heart is that of his infected prostate gland. Besides making him aware of the immediacy of death, the two diseases also prevent him from fully participating in life. Emotions and sexuality are the two things he could not appreciate: the former he escapes from by rationalization, and the latter he could not fully enjoy because of his awareness of its animality as well as his infected prostate gland. At the few moments of emotional or sexual union with the others, therefore, Todd ends up detaching himself; after the few experiences of emotional intensity, he rationalizes them into understandable positions. In order to master his physical and emotional existence, Todd has two ways of rationalization. The first one is to write his Inquiry. This Inquiry into the reason for his father's suicide is to him an endless and timeless project, thus "counterbalanc[ing] the immediacy of a one-day-at-a-time existence" (49). The second way to master his weak heart is to rationalize into new masks the changes of his attitudes toward life in his dilemmas caused by sex and/or death--his having sex with Betty June, the German soldier's and his father's death, and the awareness of his own death. The masks of a rake, a saint, and a cynic, then, as "the answer to [each of his] dilemmas" (15), serve to hide his enigmatic heart from him and to provide him a false sense of control over his life. In these two ways, Todd has always tried to maintain a rational control over his life--to overcome his fear of death and to detach himself when he may be emotionally involved. One obvious example of how he exerts his control is in his relationship with the Macks. Being "surprised" by Jane Mack's offer of herself, Todd is inadvertently lead into the triangular relationship at first, but then he actively plays a role by lying about his virginity. Immediately after he gets home from the trip with the Macks, Todd assumes a rational control over the affair by drawing an outline of what has happened and what may happen in the future. Always keeping a close watch over the development of the affair, Todd thinks he is scarcely involved in the affair. When the Mack couple's plans of the affair, as well as "the excess of their love for [Todd]," become unbearable, Todd takes measures according to his outline to end their relationships. Todd's attempts at having a rational control over his life, whether through his outlining of the triangular affair or his wearing masks, are doomed to fail in life with all its contingencies and unpredictability. Many things happen against Todd's expectations and plans. At "the end of his outline," for instance, two things happen--Jane's pregnancy and Harrison's "important statement" about whose fault the affair is--which nullify the finality of Todd's outline and lead to the resumption of the affair. Neither can the masks, as "some kind of coherent and arguable positions," be final and indestructible (201). The masks being rationalizations after his spontaneous reactions to certain situations, Todd has to adopt a new mask as the old one wears thin through the changes in his life. These successive masks have been successfully "hid[ing Todd's] heart from [his] mind" (219) until Jane's simple question about his clubbed fingers brings him to a realization that, after all, "[his] heart is the master" and that no mask could master this fact (222). Overcome by a great sense of despair over the futility of wearing masks as a way of control, Todd, to his embarrassment, does a thing completely without disguise or mask--he lies shuddering in Jane's lap until he falls asleep. This undisguised expression of his emotion, nevertheless, is done only temporarily and without anyone's noticing it. The next day when he wakes up, Todd thinks of the last way to be in control--"to master the fact of [his] living with [his heart] by destroying [him]self" (223). This day when he plans to exert the last control over his life, however, witnesses not only the failure of his control over both his life and the others' life, but also an exhaustion of his rational inquiry. It is on this day that Todd loses, or gives up, the control he always thought he had over the Macks. Being the lawyer of Harrison's lawsuit over his father's will, Todd knows that, holding an evidence in favor of Harrison's side, he is the one who decides whether Harrison will get the inheritance or not. So he plans to observe Jane's and Harrison's behavior on the day of his planned suicide in order to make the decision whether to send out the evidence or not. This plan, however, is frustrated, for Jane's reaction to Todd's insulting letter does not fall into either of Todd's preconceived categories, which leaves Todd not knowing "how to feel about the Macks at all" (211). He thus gives up his rational control by flipping a nickel in order to decide what to do and then do against what is decided by the nickel. Neither is Todd in control of his affair with Jane as he had been after its resumption. After the night of his sexual impotence and total despair, Todd thought he would be the one that ends the affair as well as the three's lives. Against his expectations, however, it is the Macks that first make the decision to terminate their relationships and tell him so on the day of his planned suicide. In their last talk together, Todd sees Harrison and Jane "fused into one person, entirely self-sufficient" (208; my emphasis). The last plan to be thwarted is that of his committing suicide. Todd planned to blow up the floating opera to kill himself as well as those around him; however, out of unknown reason, the gas he lets out in the dining room does not explode. Apart from the failure of all these rational controls over his and the others' life, Todd's rationalization in his Inquiry reaches a dead end, which paradoxically denies the reason for his ending his life. After making the decision of committing suicide, Todd tries to find reasons for his doing so. The process of his rationalizing on this day is "an awesome one," starting from a denial of any value to that of any reason for living (from "Nothing has intrinsic value" to There is no final reason for living"). This denial of any reason for living, Todd knows, easily leads to "the simple fact that there are no ultimate reasons" (201)--the "abyss" of nihilism. In one sense, this is the dead end of human rationality: since there are no ultimate reasons, there is no point rationalizing, or making Inquiry after reasons. In another sense, however, Todd's nihilism allows for a new beginning of life, since it denies reasons for both living and dying. The exhaustion of human rationality is symbolically played out in the little girl Jeannine's insistent questions about the showboat. "That's the end of the line again," Todd answers after many of Jeannine's "Why"s (195; my emphasis). Life is also implied in this exhaustion of reasons, since the question Todd could not answer is why "[the actors] have to eat to stay alive. They like staying alive." Life, as it is implied here, goes on, despite the futility of human rationality in face of the universal irrationality. Todd's life, too, goes on when his rational control is exhausted. Jeannie's question is thematically relevant also because of the focus of her questions--the floating opera, the dominant symbol in the novel which shows its self-reflexivity. In a sense, the novel is about different ways of building boats, or human construction of meanings, including its own. One of these "boats" is Adam's Original & Unparalleled Floating Opera. As Tony Tanner points out, "the show on board [the showboat] is a very old one, very corny, full of the same old gags, the same old roles, the same old acts,--like life itself" (234). This showboat, again like life, is always there floating on the river, despite Todd's inability to tell Jeannine its purpose, despite the audience's ridicule of the actor's recitation of the famous lines from Hamlet, and despite Todd's attempt to blow the boat up. Before the novel The Floating Opera, all the "boats" Todd builds, as forms of escape, fail to float on the river (of life). The two real boats he attempted to build are for the purpose of escape: "to slip quietly from [his] mooring, to run down the river... to the endless oceans" (57). Being severely beaten by Betty June, Todd wonders why the whole thing is not "a sailboat" which "would luff up into the wind and hang in stays, and [he] would sleep" (132). The philosophical positions he takes, or masks he wears, are also compared to "rowboat" (225). They are, as is shown above, an escape from "the fact" of his life. The law Todd is interested in, moreover, is explicitly compared to the floating opera ("never did there exist such an unparalleled floating opera as the law in its less efficient moments"; 169). Todd's interest in the law shows his cool detachment and irresponsibility. As LeClair rightly points out, "the law" as a floating opera is for Todd "an object of play" (718). Todd is interested in the Morton and the Mack cases because both cases have their "glorious intricacies." I, however, differ from LeClair and Harris, who follows LeClair's argument, in my interpretation of Todd's narrative as a floating opera. To LeClair, the "ideal floating opera" that resembles life is not the "real floating-opera principle" at work in the novel. The real floating-opera principle "denies man's responsibility to the integrity of fact and what the mundane world should seriously call truth and affirms his right to manipulate given conventions for his own protection and interest" (719). There is, in fact, no essential difference between this "ideal" and "real" floating opera principles as is postulated by LeClair. The floating opera principle, whether real or ideal, denies "man's responsibility to the integrity of fact and...truth" simply because, to Barth, there is no fact that does not invite contradictory interpretations and there is no absolute truth for which man can be responsible. Art, therefore, is necessarily "a representation of distortion." The reason that Todd manipulates given conventions, in consequence, is "not for his own protection and interest" but to expose the artificiality of art. His art, in other words, is not "an evasion of responsibility" as LeClair puts it, but an acknowledgement of the arbitrariness and incompleteness of any human construction, or understanding, of life. Todd, first of all, makes it very clear through his authorial intrusions, his exposure of his techniques, his various typographical marks as well as his calling his work a floating opera, that the novel is an artificial construct. Even John Barth himself points out in the copyright page that "all of the characters in this book are fictitious." Moreover, the novel, as "an explanation" of why he changes his mind has to be arbitrary but incomplete. As he points out, for instance, there may be several reasons for Betty June's murderousness other than the one he gives. His own explanation may not be right, since like everybody else, he has his own blind spots--"quite frequently things that are obvious to other people aren't even apparent to [him]" (139). Besides, "causation," after all, "is never more than an inference; and any inference involves at some point the leap from what we see to what we can't see" (214). The reason for his father suicide, therefore, is ultimately unknowable. Also, the "fact" he presents may not correct, since his memory may fail. Within one day, as Todd points out, he has three lapses of memory, and he could not even remember whether the day of his planned suicide is June 20 or 21. Nevertheless, "things that are clear to [Todd] are sometimes incomprehensible to others" and this fact occasions the whole book (140). Todd's narration, for all its incompleteness, arbitrariness and its apparent randomness, has its own order and its own truth. His narration is apparently random and disordered, the disconnected chapters on one day (Chapters 2, 4, 6, 9, 11, 12, 16, 18, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27) mixing with the other chapters on the past events and on his reasons and premises. This narration, as Todd himself points out, is like a floating opera, "float[ing] willy-nilly on the tide of [his] vagrant prose: you will catch sight of it, lose it, spy it again" (7). What he wants to convey both through the content (the exhaustion of his rational control) and the order of his narration is that life can only be perceived as a floating opera, on which people meet and part, things converge and diverge without obvious reasons. In order to understand life, as well as Todd's narration, we need to "fill in the gaps" and construct meaning out of its randomness. The novel as a floating opera, then, is not simply composed of Todd's "lies" (Harris 19). Rather, it contains truth about life and its writing means a new stage of Todd's life after the dead end he meets. At this point, Todd realizes that Hamlet's question (of to be or not to be) is meaningless and that there are no ultimate reasons for anything. This, however, does not stop Todd from making inquiries. His inquiries, as a matter of fact, will still be endless, but they are no longer an escape from the fear of death but an explanation of why he lives on and an embrace of all the possibilities in life. Moreover, his emphasis now is more on communication--with his father in the Letter to My Father, and with his readers in The Floating Opera. If Barth makes Todd Andrews get away from the dead end of his rationality to accept relativism, or the "less-than-absolute values," in the beginning of The End of the Road he places Jake Horner and Joe Morgan at the two extremes of relativism-the former with his immobility, and the latter with his inherent absolutism. As Barth himself puts it, "I deliberately had [Todd Andrews] end up with that brave ethical subjectivism in order that Jacob Horner might undo that position in # 2 and carry all nonmythical value-thinking [i.e. thinking based on relative values] to the end of the road" (Bluestone 586). In other words, what The End of the Road does is to push relativism, the conclusion of The Floating Opera, to two extremes in order to make artistic construction a new way of living. One of the two extremes of relativism is Jake's immobility, or in Barth's terms, cosmopsis (the cosmic view). Jake sees too many choices in life to make his own choice, so he is sometimes "held static like the rope marker in a tug-o'-war where the opposing teams are perfectly matched" (5). Throughout the novel, he continually identifies himself with the statue of Laoco™n. Jake's eyes, like Laoco™n's, are "sightless, gazing on eternity, fixed on ultimacy" (74) His limbs, like Laoco™n's too, are bound "by the serpents Knowledge and Imagination, which...no longer tempt but annihilate" (196). Joe also regards every value as relative, but he chooses certain "less-than-absolutes" for himself and sticks to them as absolute values. Nothing, to Joe, is ultimately defensible, but "a man can act coherently" (47). While Jake is either immobilized or self- contradictory, Joe acts efficiently and consistently according to his values. If Jake has no fixed identity and sometimes no "weather"; Joe is always so sure of his ground that both his face and his action express faithfully what he has in mind. Both Jake and Joe, though to different degrees, like to rationalize, Jake in his clever argument with Rennie and Joe in his insistent pursuit of a definite answer. Moreover, as Harris rightly points out, they both "exhibit the close attention to minute details [e.g. how many times Jake and Rennie make love, and in what positions] that reflects Todd Andrews's need to be in rational control" (33). 1 1 Nevertheless, life, with all its Both Harris and Morrell equate Jake with the Todd before his suicide attempt, and Joe with the Todd after the attempt (Harris 33; Morrell 19). There are, indeed, similarities between Todd and Jake and Joe in terms of their attempts at rational control. However, I contingencies and unknowability, is beyond the rational control of either Todd Andrews in The Floating Opera or Jake in The End of the Road. As the Doctor puts it, "The World is everything that is the case, and what the case is is not a matter of logic" (81; emphasis mine). Despite their attempts at rational control, therefore, Todd Andrews experiences toward the end of one day's rationalization the "abyss" of nihilism, while Jake faces at the end of his road "the raggedness of [life]; the incompleteness" (196). The ways for Jake to get away from this total meaninglessness and his immobility, like Todd Andrews's, through the various human "constructions" of meanings. But this time they are ways suggested by the Doctor for therapeutic purpose: first to teach rules, then to play roles (Mythotherapy), and finally, to write a fiction (Scriptotherapy). The Doctor, first of all, asks Jake to teach "the truth about grammar" (5). But, as he later finds out, Mythotherapy may be more suitable for Jake, since before he suggests it, Jake is unconsciously playing roles. Before the school's appointment committee, Jake acts as an idealistic and devoting teacher, turning his smile on and off as he wishes. With Peggy Rankin, he plays the role of an irresponsible young man, or a cad, and assigns her the role of "Forty-Year-Old Pickup." After knowing Joe and Rennie better, Jake unconsciously imitates Joe and plays his double. Like Joe, Jake likes to test her, so he makes challenging remarks to her only to observe her reactions. After Rennie compares Joe to God, Jake willingly takes the part of the Devil and invites Rennie to peep at Joe. Jake's role-playing, as a matter of fact, is a form of fictionalization that everybody consciously or unconsciously does out of their life. As the Doctor puts it, "we're the ones do not agree with these equation, which simplify the story and make them sound like rigid arrangement of ideas. who conceive the story, and give other people the essences of minor characters" (89). In being a "casting director" of our life and assigning roles to others, we necessarily distort the actor's personalities. This distortion, like that of any other human constructions, is both inevitable in this mysterious life and necessary if one would like to act in life, or to "get on with the plot" (143). Role-playing, however, are not without its dangers. First of all, "no man's life story as a rule is ever one story with a coherent plot," but a person may not know how to revise his script as the situation changes and thus exerts a tyrannical control over his "minor characters." Secondly, despite the Doctor's suggestion to Jake to keep out of any involvement, human involvement is necessarily the result of "real" persons' playing the roles. Moreover, there must be conflicts between different "writers" and their scripts. Being involved in such entangled situations, a person may be carried away with his role and lose the self-consciousness he should have in playing a role. Joe and Jake respectively fall into these two dangers, which lead to the tragedy of Rennie's death. Joe, with his strong will and consistent principle, is the "writer" not only of his life, but of Rennie's. The ideal script he writes for both of them is that they take each other seriously, and are frank and faithful to each other. He thus assigns a consistent role of self-sufficiency to Rennie and expects her to live up to it. To him Rennie is also his "favorite prot‚g‚" (37) in need of his tutoring and guidance, so he constantly keeps an eye on her, and hits her when she does not meet his expectations. Joe, moreover, sets a scene of Jake's taking the daily horse-riding lessons with Rennie to try her fidelity and selfsufficiency. Against Joe's expectations, however, Rennie is not self-sufficient at all. As she herself puts it, she is "a complete zero," and she needs Joe's support like that of a God. The scene of horse-riding arranged by Joe puts Rennie in a tug-of-war between her "God" and Jake as a Devil. When Rennie makes love to Jake out of reasons she could not face, Joe sticks to his old script and insists on their playing the same roles. He, therefore, is a doctor that "keep[s] the wound open and until [he knows] just what kind of wound it is" (146) while she is asked to be "frank" to her doctor and to her desire. The other factor involved in this tragedy is Jake's loss of self-consciousness in playing a role. After the Doctor suggests Mythotherapy to him, Jake most of the time keeps his self-consciousness in taking different roles, the one part of him watching the other part assuming one role after another. First of all, he imitates Joe when he is with Peggy, rationalizing his view of love and hitting her. At two crucial points, however, Jake loses his rational control, or his self-consciousness. The first time is when he makes love to Rennie without conscious motivation. The adultery, to him, is "unpremeditated and entirely unreflective." When he first makes love to Rennie, Jake claims, there is nothing on his mind "other than [some] half-articulated sentiments" (101). The second time was when he feels a sudden sense of guilt several days after the adultery. His anguish at that moment, as he himself says, is "pretty much unself-conscious" (103). Against the Doctor's warning, Jake at these two points is "caught without a script," and thus involved to play a part he is not conscious of. After Joe finds out about the adultery and sticks to what then becomes a sadistic melodrama of "frankness," Jake resumes his self-consciousness in playing the roles of a coward, a paradoxist, and a penitent. In other words, both of them with their different scripts seek to keep a rational control over the situation which is growing out of their control, especially after the discovery of Rennie's pregnancy. In face of this new situation, Joe insists on assigning a role of self-sufficiency to Rennie, while Jake designs one script after another in order to get an abortion. Neither of their scripts, however, help Rennie, who takes the former's role of self-sufficiency and the latter's suggestion of abortion, only to meet her grotesque death at the operation table. The last telephone dialogue between Jake and Joe is symptomatic of the dead ends they reach respectively. On the one side of the telephone, Joe keeps asking Jake for his plans, his reasons, and his thoughts, while on the other side Jake can only repeat "I don't know, ...I said I don't know what to do." (197). What Jake doesn't know at this point is not only what to do, but also how to judge ("merciful or cruel"; "right or wrong") and what to feel. With Joe's pressing for answers and Jake's complete immobility in terms of action, thought and feeling, the two cannot simply communicate. Jake is then left alone in the dark with a "dead instrument" of communication and the exhaustion of roles, plans and rational control as a defense against the meaningless universe. The "terminal" Jake heads for in the next morning, however, marks the beginning of a new stage of his life in which he undergoes another of the Doctor's therapies-Scriptotheraphy, or turning his life into the fiction The End of the Road. Contrary to the danger of involvement and the lack of consciousness that Mythotherapy may have, in writing a fiction Jake maintains both his detachment from reality and his consciousness of the arbitrariness and fictitiousness of his writing. As David Majdiak puts it very well, "while Mythotherapy deals with people and attempts to control their lives, Scriptotherapy deals solely with form, with fiction" (Waldmeir 108). In dealing only with form or language but not with people, therefore, Jake maintains a distance from life. But this does not mean that he alienates himself from life, since writing allows Jake to make sense of life and to "feel [like] a man, alive and kicking" (119). Jake, like Todd in The Floating Opera, not only is aware of but exposes the fact that the fiction he writes is only a verbal construction of reality but not reality itself. First of all, he makes it clear that The End of the Road is only "one" story of his life, while "the same life lends itself to any number of stories--parallel, concentric, mutually habitant..." (5).2 Moreover, Jake puts the story of his life in one sentence, or in "the latter member of a double predicate nominative expression in the second independent clause of a ...sentence" (5; 3). In this way, he again implies that a life-story is nothing but language composed of grammatical parts. Being a verbal construction, Jake's story has to be incomplete, since ultimately the reality behind his language cannot be known. In consequence, Jake, like Todd, purposely makes us aware of the uncertainties and incompleteness of his narrative. We do not know, for instance, whether Jake's appointment with the school committee is on Monday or Tuesday, since the only proof, the committee's letter, is thrown away. We do not know either what Rennie and Joe actually say; what we get is, as Jake tells us, his condensation "for convenience's sake" of their words into a few uninterrupted paragraphs. More importantly, we do not know the reason for Jake and Rennie's first sexual intercourse, though we do get some possible reasons for Jake's interest in Rennie here and there in Jake's verbal construction. The superficial reason Jake gives is his carnal desire and masculine curiosity (101), while the reason Rennie reveals to Jake--their peeping at Joe and finding him masturbating and picking nose at the same time--is one possibility that they dare not mention to Joe (138). Another implicit reason is Jake's sadism, which makes him "interested" in Rennie when he knows that she was hit twice by her husband, 1 2 Fourteen years later, when Jake reappears in Barth's novel LETTERS, he extends this point of the fictitiousness of his story. He wrote to himself, "...this account [What I Did Until the Doctor Came] became the basis of a slight novel called The End of the Road (1958), which ten years later inspired a film, same title, as false to the novel as was the novel to your Account and your Account to the actual HornerMorgan-Morgan triangle as it might have been observed from either other vertex" (19). and makes him like her all the more because Rennie is in torment after their adultery. But on the other hand, Jake exhibits genuine sympathy for Rennie, since, in fact, they are like each other--empty inside. A more implicit reason we may find out from Jake's narrative is that Jake, in being Joe's double, plays the role of the Devil and Unreason respectively when Joe is a God and Reason. Between them Rennie becomes the object they have to win over in order to prove themselves. All of these seemingly contradictory reasons may be Jake's reasons, and, as Jake points out, there is simply no "key" to people's character except in fiction (131). "There are," as Todd finds out, "no ultimate reasons," but at the same time there are many possible reasons for Betty June's murderousness, for Todd's plan of suicide as well as for Jake and Rennie's sexual intercourse. The purpose of their verbal constructions is neither to find out the ultimate reason, nor to tell lies or escape facts (Harris 29; Ziegler 27), but to construct a meaning out of their life and also to expose the inevitable distortion of their constructions. As Jake puts it, "to turn experience into speech...is always a betrayal of experience, a falsification of it, but only so betrayed can it be dealt with at all" (119, my emphasis). Both Todd's and Jake's narrative "distortions," therefore, are not only inevitable but necessary; they are, in fact, a way for the narrators to explore life and to participate in life. Their way of living, of course, is not the way, just as the meaning they construct is not the meaning of life. At the end of Jake's explication of "articulation" as his absolute, he undermines the "absoluteness" of his feelings about writing by saying "In other senses, of course, [he doesn't] believe this at all" (119). Barth, likewise, undermines in The End of the Road the relativism Todd arrives at at the end of The Floating Opera by pushing it to two extremes, Jake's immobility and Joe's absolutism. In his third novel The Sot-Weed Factor, furthermore, he problematizes Jake's artistic detachment by contrasting the innocent Eben who seeks to detach himself from the polluted world to the Cosmic Lover Burlingame who embraces the world's contradictions and knows how to play roles in life. His first twin novels, therefore, involve an exhaustion which is not a dead end and give an answer which cannot be the final answer. By turning "the felt ultimacies of [his] time into material and means for his work" Barth as the artist "transcends what had appeared to be his refutation" (Friday Book 64). What Barth transcends both through the content and style of The Floating Opera and The End of the Road, then, is the attempt to rationalize, to control and the realistic impulse to tell the truth and find the answer. The answer he provides in these two novels and continuously revises in his later ones is the nature and value of an artistic "distortion" of life. Works Cited Barth, John. The Floating Opera. New York: Bantam, 1967. ---. The End of the Road. New York: Bantam, 1967. ---. The Friday Book: Essays and Other Nonfiction. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1984. ---. LETTERS. N.Y.: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1979. Bluestone, George. "John Wain and John Barth: The Angry and the Accurate." Massachusetts Review 1 (May 1960): 582-589. Cooper, Arthur. "An In-Depth Interview with John Barth." Harrisburg Patriot 30 (March 1965): 6. Glaser-wohrer, Evelyn. An Analysis of John Barth's Weltanschauung: His View of Life and Literature. Salzburg, Austria: Institut Fur Englische Sprache Und Literatur, 1977. Harris, Charles B. Passionate Virtuosity: The Fiction of John Barth. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 1983. LeClair, Thomas. "John Barth's The Floating Opera: Death and the Craft of Fiction." TSLL 14 (1973): 711-30. Morrell, David. John Barth: An Introduction. Univ. Park: The Penn State UP, 1976. Prince, Alan. "An Interview with John Barth." Prism (Sir George Willaims U, Spring 1968): 42-62. Stark, John. The Literature of Exhaustion: Borges, Nabokov and Barth. Durham: Duke UP, 1975. Tanner, Tony. City of Words: American Fiction 1950-1970. New York: Harper & Row, 1971. Waldmeir, Joseph J. Critical Essays on John Barth. Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1980. Ziegler, Heide. John Barth. New York: Methuen, 1987.