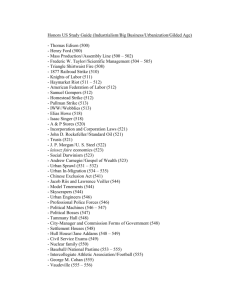

Exh 2: WORD version of [Proposed]

advertisement

![Exh 2: WORD version of [Proposed]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008482114_1-3a1da58871a029b6129b0167eba88497-768x994.png)

1 2 3 4 5 6 MARK J. KENNEY (State Bar No. 87345) ERIK KEMP (State Bar No. 246196) ek@severson.com SEVERSON & WERSON A Professional Corporation One Embarcadero Center, Suite 2600 San Francisco, CA 94111 Telephone: (415) 398-3344 Facsimile: (415) 956-0439 Attorneys for Plaintiff and Cross-Defendant FORD MOTOR CREDIT COMPANY LLC 7 8 SUPERIOR COURT OF CALIFORNIA 9 COUNTY OF SANTA CLARA 10 11 Coordination Proceeding Special Title (Rule 3.550) 12 FORD MOTOR CREDIT COMPANY 13 REES-LEVERING ACT CASES JUDICIAL COUNCIL COORDINATION PROCEEDING NO. 4660 14 Included actions: 15 Ford Motor Credit Company LLC v. Bretado, et al., 16 Complaint filed: 11/05/2010 17 Ford Motor Credit Company LLC v. Arambula, et al., 18 Complaint filed: 12/07/2010 19 20 Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles No. NC 055542 Superior Court of California, County of Santa Clara No. 110cv189080 [PROPOSED] ORDER SUSTAINING FORD MOTOR CREDIT COMPANY LLC’S DEMURRER TO THE FOURTH CAUSE OF ACTION AND MOTION TO STRIKE PUNITIVE DAMAGE ALLEGATIONS 21 22 Plaintiff and cross-defendant Ford Motor Credit Company LLC’s demurrer to the 23 consolidated amended cross-complaint’s fourth cause of action and motion to strike the 24 consolidated amended cross-complaint’s allegations of and prayer for punitive damages was set 25 for hearing on March 23, 2012. The Court issued a tentative ruling on March 22, 2012, that 26 neither party contested. The Court, therefore, adopts as its final ruling its tentative ruling, which 27 reads as follows: 28 08888/1739/2168002.1 [Proposed] Order Sustaining Ford Credit’s Demurrer and Granting Motion to Strike 1 This cross-action is a consolidated class action alleging unlawful, unfair and deceptive 2 practices of cross-defendant Ford Motor Credit Company LLC (“FMCC”) in connection with the 3 repossession of motor vehicles. Cross-complainants Pilar Bretado and Lisa Arambula (“Cross- 4 Complainants”) allege that FMCC fails to provide borrowers under conditional sales contracts 5 with statutorily-mandated notice of their legal rights and obligations after repossession of 6 vehicles, provides notices in typeface that fails to comply with the Rees-Levering Act, wrongfully 7 deprives consumers of their right to reinstate or redeem their conditional sales contracts after 8 repossession, negligently and/or fraudulently misrepresents the rights and obligations of the 9 parties following repossession, collects or seeks to collect deficiencies from borrowers following 10 repossession for which borrowers are not liable as a matter of law, and unlawfully and falsely 11 reports borrowers’ deficiency balances to credit reporting agencies as past due debts when 12 collection of said amounts is unlawful.1 13 The Consolidated Amended Class Cross-Complaint (“CACCC”) asserts four causes of 14 action for: (1) declaratory relief (by Cross-Complainants); (2) violations of the Rees-Levering 15 Act, Civil Code §§ 2981 et seq. (by Cross-Complainants); (3) violation of Business & Professions 16 Code section 17200 et seq. (by Cross-Complainants); and (4) Consumers Legal Remedy Act 17 (“CLRA”), Civil Code §§ 1750 et seq. (by Arambula). 18 The CACCC alleges that Arambula signed a conditional sale contract to purchase a used 19 car from a dealer in Santa Clara County on or about July 10, 2004, and the dealer later assigned 20 that contract to FMCC.2 FMCC repossessed Arambula’s vehicle in early 2010 because she 21 allegedly defaulted on the installment payments that were due under the contract, and thereafter 22 mailed a notice to Arambula on or about January 21, 2010.3 FMCC sold Arambula’s vehicle on 23 or about March 9, 2010 and assessed a deficiency balance against her.4 According to the 24 25 1 Consolid. Amend. Class Cross-Compl. (“CACCC”) ¶ 1. 2 CACCC ¶ 10. 3 CACCC ¶ 11. 4 CACCC ¶ 12. 26 27 28 08888/1739/2168002.1 -2[Proposed] Order Sustaining Ford Credit’s Demurrer and Granting Motion to Strike 1 CACCC, FMCC falsely represented to Arambula that she owed a deficiency balance, when in 2 fact she did not because of FMCC’s noncompliance with the Rees-Levering Act.5 3 In the fourth cause of action under the CLRA, Arambula alleges that she and the class 4 members are “consumers” and FMCC is a “person” within the meaning of the CLRA, and the 5 vehicles that are the subject of the class member contracts held by FMCC are “goods” within the 6 meaning of the CLRA.6 Arambula alleges that FMCC has violated the CLRA by representing 7 that it is entitled to collect the deficiencies on these contracts and by claiming that Arambula and 8 the class members are liable for those deficiencies.7 Arambula further alleges that because 9 FMCC failed to send notices that complied with Rees-Levering, Arambula and the class members 10 11 are not liable for the deficiencies and FMCC is not entitled to collect on them.8 FMCC demurs to Arambula’s CLRA claim on the ground of failure to state sufficient 12 facts. FMCC also moves to strike the words “punitive damages” in paragraphs 31 and 65, and the 13 prayer paragraph 11. 14 Judicial Notice 15 FMCC’s request and supplemental request for judicial notice of thirteen court records 16 filed in three unrelated lawsuits is DENIED. 17 Demurrer 18 FMCC argues that the CLRA claim fails because the CLRA does not apply to a loan or 19 extension of credit. FMCC contends that under the law, a loan or extension of credit is not a 20 “transaction” within the CLRA’s scope, as it involves no sale or lease of goods or services to 21 consumers. FMCC further argues that the CLRA is not applicable to ancillary activities a lender 22 or financier may subsequently perform after the loan is originated or credit extended, and thus, 23 the CLRA cannot validly be based on the allegedly defective “Notice of Intent” or “NOI,” since 24 25 5 Ibid. 26 6 CACCC ¶¶61-63. 27 7 CACCC ¶ 64. 28 8 Ibid. -3- 08888/1739/2168002.1 [Proposed] Order Sustaining Ford Credit’s Demurrer and Granting Motion to Strike 1 the NOI is not a good (“tangible chattel”), and it does not constitute work, labor or services, and 2 the sending of an NOI is not intended to result and does not actually result in the sale or lease of 3 goods or services to consumers. FMCC argues that its allegedly wrongful attempts to collect 4 Arambula’s deficiency and furnishing of information to credit bureaus also falls outside of the 5 CLRA’s scope, and its post-default collection activities are intended to secure repayment of the 6 debt, not to sell any new goods or services. Finally, FMCC argues that even though Arambula 7 alleges her former vehicle is a “good” for CLRA purposes, this case is not about the vehicle, as 8 Aramabula does not allege any deceptive conduct in the sale of the vehicle, and all her charging 9 allegations pertain to post-sale conduct (e.g., sending of the NOI in January 2010, collection 10 11 attempts). Arambula argues that her purchase of the car was a “transaction” within the meaning of 12 the CLRA, and part of the deal was that the dealer would hold title until Arambula paid all the 13 installments, while the holder of the contract would give all notices required by law in the event 14 of default and repossession. Arambula contends that the assignment of the contract to FMCC did 15 not convert the sale of a car into a pure financing transaction. Arambula cites federal authority 16 (Van Slyke v. Capital One Bank (N.D. Cal. 2007) 503 F.Supp.2d 1353) for the position that if 17 extension of credit is not separate and apart from the sale of a good, the CLRA applies, and here, 18 FMCC, the holder of Arambula’s car contract, stepped into the shoes of the dealer that sold her 19 the car and extended credit. 20 The CLRA prohibits any person from engaging in unlawful or deceptive acts or practices 21 intended to result in the sale or lease of goods or services to any consumer. (Civ. Code § 1770, 22 subd. (a).) The CLRA is to be liberally construed, and the remedies it provides are cumulative to 23 any other procedures or remedies for any violation or conduct provided for in any other law. 24 (Civ. Code, § 1752.) Under section 1770 of the CLRA, it is illegal to advertise goods or services 25 with the intent not to sell them as advertised (§ 1770, subd. (a)(9)), to make false or misleading 26 statements of fact concerning reasons for, existence of, or amounts of price reductions (§ 1770, 27 subd. (a)(13)), or to represent that a transaction confers or involves rights, remedies, or 28 obligations which it does not have or involve, or which are prohibited by law (§ 1770, subd. -408888/1739/2168002.1 [Proposed] Order Sustaining Ford Credit’s Demurrer and Granting Motion to Strike 1 (a)(14)). The CLRA “defines ‘goods’ as ‘tangible chattels bought leased for use primarily for 2 personal, family, or household purposes, including certificates or coupons exchangeable for these 3 goods, and including goods that, at the time of the sale or subsequently, are to be so affixed to 4 real property as to become a part of real property, whether or not severable from the real 5 property.’ (Civ. Code, § 1761, subd. (a).) It defines ‘services’ as ‘work, labor, and services for 6 other than a commercial or business use, including services furnished in connection with the sale 7 or repair of goods.’ (Id., § 1761, subd. (b).)” (Fairbanks v. Superior Court (2009) 46 Cal.4th 56, 8 60-61.) The CLRA defines “transaction” as “an agreement between a consumer and any other 9 person, whether or not the agreement is a contract enforceable by action, and includes the making 10 11 of, and the performance pursuant to, that agreement.” (Id., at § 1761, subd. (e).) In Berry v. Am. Express Publishing, Inc. (2007) 147 Cal.App.4th 224, the Court of Appeal 12 held that the extension of credit, such as issuing a credit card, separate and apart from the sale or 13 lease of any specific goods or services, does not fall within CLRA’s scope. (Berry, supra, 147 14 Cal.App.4th at p. 227.) Arambula validly points out that here, the initial extension of credit was 15 not separate and apart from the sale or lease of goods, and was made in connection with her 16 vehicle purchase. However, the alleged act giving rise to the CLRA claim is FMCC’s service of 17 NOIs that do not comply with the Rees-Levering Act, and which contain alleged 18 misrepresentations that FMCC is entitled to collect on the deficiencies in the contracts.9 This is 19 not an act that falls within the prohibited conduct set forth in Civil Code section 1770 subdivision 20 (a) of the CLRA, which prohibits certain “unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive 21 acts or practices undertaken by any person in a transaction intended to result or which results in 22 the sale or lease of goods or services to any consumer… .” (Civ. Code, § 1770, subd. (a), italics 23 added.) In other words, no matter how misleading the NOI is with regard to FMCC’s right to 24 collect on the deficiencies, FMCC’s service of the NOI to consumers is not a transaction intended 25 to result in the sale or lease of goods or services to any consumer. Rather, it is reasonably 26 construed as intended to obtain repayment of the existing debt. 27 28 9 See CACCC ¶ 64. -5- 08888/1739/2168002.1 [Proposed] Order Sustaining Ford Credit’s Demurrer and Granting Motion to Strike 1 Arambula argues that “transaction” is defined in the CLRA to include not only the making 2 of the contract, but the performance pursuant to it, and when FMCC decided to purchase 3 Arambula’s contract from the dealer, FMCC undertook all the contractual benefits and 4 obligations, including the duty to perform according to the contract terms. However, the 5 definition of “transaction” in section 1761 subdivision (e) must still be read in conjunction with 6 section 1770(a), which adds that the transaction must be “intended to result or which results in the 7 sale or lease of goods or services to any consumer.” The CACCC fails to allege facts that would 8 suggest that FMCC’s post-default actions were intended to sell or lease goods or services to a 9 consumer. 10 11 For these reasons, the demurrer to the CLRA cause of action is SUSTAINED with 10 days’ leave to amend. 12 Motion to Strike 13 FMCC moves to strike the words “punitive damages” from paragraphs 31 and 65 of the 14 CACCC, and paragraph 11 of the CACCC’s prayer. FMCC argues that punitive damages are 15 improper because the CLRA is the only claim in the CACCC that would potentially permit a 16 claim for punitive damages, and if the Court sustains the demurrer, the request for punitive 17 damages will then be improper. FMCC further argues that even if the demurrer is overruled, the 18 request for punitive damages should still be stricken because there are no facts alleged showing 19 oppression, fraud or malice to support the award of such damages. 20 Arambula argues the motion should be denied because the CLRA does not require 21 alleging oppression, fraud or malice, and the motion is premature because she has not completed 22 discovery or had the opportunity to present her case. 23 Under the CLRA, “[a]ny consumer who suffers any damage as a result of the use or 24 employment by any person of a method, act, or practice declared to be unlawful by Section 1770 25 may bring an action against that person to recover…[p]unitive damages.” (Civ. Code, § 1780, 26 subd. (a)(4).) The motion to strike is MOOT as to paragraph 65, which is contained within the 27 defectively-pled CLRA cause of action. 28 -608888/1739/2168002.1 [Proposed] Order Sustaining Ford Credit’s Demurrer and Granting Motion to Strike 1 Punitive damages are not available pursuant to the UCL cause of action, as relief under 2 the UCL is “generally limited to injunctive relief and restitution.” (Walker v. Countrywide Home 3 Loans (2002) 98 Cal.App.4th 1158, 1179.) The declaratory relief cause of action alleges an 4 actual controversy between the parties as to whether the Notices served by FMCC are defective.10 5 Arambula fails to allege facts that would support a finding of oppression, fraud, or malice for 6 purposes of recovering punitive damages based on this alleged controversy. (See Civ. Code, § 7 3294, subd. (a).) 8 Regarding the Rees-Levering claim, although a buyer of an automobile that is repossessed 9 may have “additional remedies” (e.g., a conversion action) for a seller’s violation of the Rees- 10 Levering Act’s notice requirements (see Cerra v. Blackstone (1985) 172 Cal.App.3d 604, 609), 11 there are still no allegations of oppression, fraud, or malice in connection with FMCC’s alleged 12 Rees-Levering violations. 13 14 15 For these reasons, the motion to strike is GRANTED with 10 days’ leave to amend as to paragraphs 31 and 11 of the prayer. IT IS SO ORDERED. 16 17 DATED: 18 Hon. James P. Kleinberg Judge of the Superior Court 19 20 21 Approved as to Form: 22 ANDERSON, OGILVIE & BREWER LLP 23 DATED: March 26, 2012 By: 24 25 /s/ Carol McLean Brewer Carol McLean Brewer Attorneys for Defendant & Cross-complainant Lisa Arambula 26 27 28 10 See CACCC ¶ 41. -7- 08888/1739/2168002.1 [Proposed] Order Sustaining Ford Credit’s Demurrer and Granting Motion to Strike