The Ohio Northern University Raabe College of Pharmacy

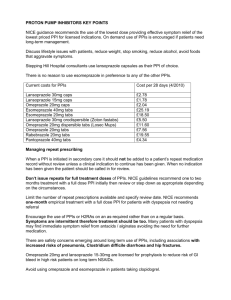

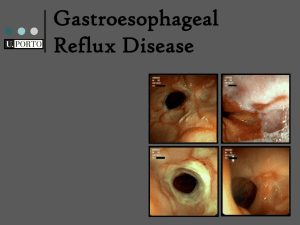

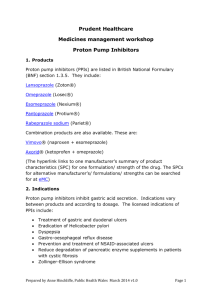

advertisement

The Family Practice Newsletter The Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine The Ohio Northern University Raabe College of Pharmacy Doctors Hospital Family Practice Volume 6, Issue 8 March, 2007 Nighttime Acid Breakthrough “A Pain” Allison Lambacher, ONU Doctor of Pharmacy Candidate Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) are both now commonly used as first-line therapy in treating patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).1 More and more patients are using both a PPI plus an H2RA in an effort to better control acid suppression, particularly at nighttime. Continuous gastric acid production at nighttime can result in nocturnal acid breakthrough (NAB), also known as nighttime acid breakthrough. NAB is arbitrarily defined as an intragastric pH of < 4 for at least an hour or more overnight while a person is on PPI therapy.2 NAB occurs in more than seventy percent of people.2-6 It even occurs in patients with GERD who are on twice-daily dosing of a PPI. Twice daily PPI therapy has been shown to be effective in adequately controlling daytime gastric pH levels, but sometimes it is not enough to also control the nighttime pH levels.4 NAB may be particularly injurious to the esophagus since there is decreased acid clearance from the esophagus while lying down in bed at night. This is why it is important to get better control of acid suppression in patients who experience NAB, especially in patients who require greater degrees of acid suppression (e.g., history of esophagitis, scleroderma, and Barrett’s esophagus). PPIs may not provide continuous 24-hour acid suppression in all patients, even in those who take PPIs twice a day as explained above. It is important to remember how PPIs work; they inhibit active acid-secreting proton pumps only. Therefore, they work best when these pumps are being activated in response to food. Ideally, patients should take their PPI thirty to sixty minutes before eating a meal so that the drug is distributed prior to activation of the acid/proton pumps. For those on a once daily PPI regimen, it is typically best to take the PPI before breakfast. However, for patients who experience NAB, it may be better to have the patient take the dose before dinner (rather than before breakfast) to try to avoid the occurrence of NAB.8 If possible, it may be beneficial to split the total daily dose in two and take half of the daily dose before breakfast and the other half before dinner.4 If twice daily PPI dosing is still ineffective, adding a H2RA at bedtime is another option.4 H2RAs work by a different mechanism than PPIs; they work by blocking histamine receptors that trigger acid production. These drugs can stop acid secretion that is caused by histamine at night, regardless of whether or not food has been consumed. Therefore, adding a H2RA at bedtime (in addition to the PPI regimen) can help to control symptoms of acid breakthrough at night. There is some concern, however, about patients developing tolerance to H2RAs with prolonged use. For this reason, it is good to try other approaches of avoiding acid reflux first, such as dietary and lifestyle modifications (e.g., sleeping with head elevated with pillows, avoiding foods that trigger acid reflux, and smoking cessation).9,10 Multiple studies have evaluated the efficacy of adding a H2RA to PPI therapy to help reduce the occurrence of NAB.1,3-6 However, theses studies evaluated a small number of patients for a short duration of time. Therefore, the clinical significance of these findings is not clear. More studies with greater numbers of patients and longer study durations are needed to evaluate the true efficacy of these combination therapies. When taking both PPIs plus H2RAs, patients should be counseled to avoid taking these medications at the same time. If taken together, the PPI may not be as effective since the H2RA will already be decreasing acid secretion. Advise patients to take twice daily PPI therapy before breakfast and dinner and to take the H2RA at bedtime. Recommended daily doses of PPIs and H2RAs for the treatment of nonerosive GERD are as follows: omeprazole (Prilosec®) 20 mg/day, esomeprazole (Nexium®) 40 mg/day, lansoprazole (Prevacid®) 30 mg/day, rabeprazole (Aciphex®) 20 mg/day, pantoprazole (Protonix®) 40 mg/day; ranitidine (Zantac®) 300 mg/day, famotidine (Pepcid®) 40 mg/day, cimetidine (Tagamet®) 1600 mg/day, nizatidine (Axid®) 300 mg/day. Doses higher than these have been used when treating hypersecretory and/or erosive disorders.8 PPIs and H2RAs are generally very well tolerated. The most common side effects seen with PPIs include headache, dizziness, and GI side effects (e.g., nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, dyspepsia, flatulence, and abdominal pain). Differences in the metabolism among PPIs may lead to specific drug interactions. The CYP450 enzymes that metabolize the PPIs vary, which makes the specific drug-drug interactions vary between them as well. Omeprazole and esomeprazole have the greatest potential for drug-drug interactions, while pantoprazole has the lowest potential for interactions. When given together, omeprazole can decrease the elimination of drugs like warfarin, phenytoin, diazepam, and cyclosporine. Monitor for increased levels of these medications when given concomitantly with omeprazole. Despite the differences in metabolism, other significant and clinically relevant interactions are not common. None of the PPIs require dose-adjustment for hepatic or renal insufficiency. The three main concerns with long-term safety of PPIs include effects of prolonged hypergastrinemia and chronic hypochlorhydria, and the possible association of PPIs with gastric atrophy. Long-term PPI use may also be associated with hip fractures and community-acquired pneumonia, but these associations have not been proven.11 H2RAs are safe drugs as well. The most common side effects seen with H2RAs include headache and GI side effects like with PPIs. Cimetidine has also been associated with gynecomastia and impotence in patients taking high doses for prolonged periods of time. Drug-drug interactions have been noted for some of the H2RAs, particularly cimetidine. Cimetidine is a potent inhibitor of the CYP450 system and therefore can decrease elimination of drugs such as warfarin, theophylline, and phenytoin. Monitor for increased levels of these drugs when given concomitantly with cimetidine. All four H2RAs are eliminated by both renal and hepatic metabolism. Dose adjustments in renal failure are advised, as increased concentration of H2RAs in elderly patients has been associated with increased side effects, such as mental status changes (e.g. confusion). The dose of all H2RAs is generally reduced by 50% in moderate to severe renal failure. Finally, absorption of Vitamin B12 depends upon gastric acid. For this reason, long-term H2RA and PPI use has been associated with serum B12 deficiency, which can be manifested as peripheral neuropathies. More data are still needed, but keep in mind the possibility of B12 deficiency in patients on chronic acid suppression.11 References: 1. Sugimoto M, Furuta T, Shirai N, et al. Comparison of an increased dosage regimen of Rabeprazole versus a concomitant dosage regimen of Famotidine with rapebrazole for nocturnal gastric acid inhibition in relation to cytochrome P450 2C19 genotypes. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005; 77: 302-311. 2. Ours TM, Fackler WK, Richter JE, et al. Nocturnal Acid Breakthrough: Clinical Significance and Correlation with Esophageal Acid Exposure. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2003; 98: 545-550. 3. Fackler WK, Ours TM, Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Long-term Effect of H2RA Therapy on Nocturnal Gastric Acid Breakthrough. Gastroenterology 2002; 122: 625-632. 4. Xue S, Katz PO, Banerjee P, et al. Bedtime H2 blockers improve nocturnal gastric acid control in patients on proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001; 15: 1351-1356. 5. Cross LB, Justice LN. Combination Drug Therapy for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2002; 36: 912-916. 6. Peghini PL, Katz PO, Castell DO. Ranitidine Controls Nocturnal Gastric Acid Breakthrough on Omeprazole: A Controlled Study in Normal Subjects. Gastroenterology 1998; 115: 1335-1339. 7. Peghini PL, Katz PO, Bracy NA, Castell DO. Nocturnal Recovery of Gastric Acid Secretion with Twice Daily Dosing of Proton Pump Inhibitors. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 1998; 93: 763-767. 8. Lacy CF, Armstrong LL, Goldman MP, Lance LL. Lexi-Comp’s Drug Information Handbook. 13th ed. Hudson: Lexi-Comp; 2005. 9. Medical Advisory Panel for the Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group. VHA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of gastroesophageal disease in primary care practice. Washington: Veterans Health Administration, Department of Defense; 2003. 10. University of Michigan Health System. Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Health System; 2002.