B189262A - Cases and Codes

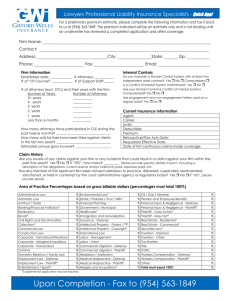

advertisement