Case Brief

advertisement

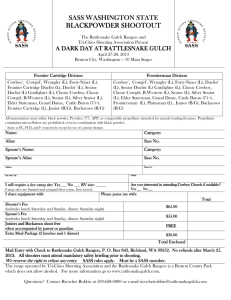

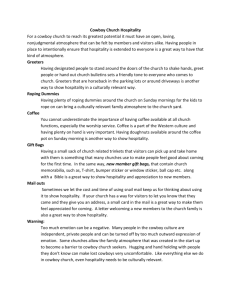

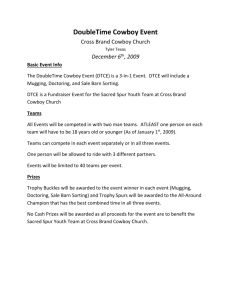

Adrian Johnson July 28, 2008 Mass Comm. Law Research Brief The Naked Cowboy(s)? Robert Burck aka: The Naked Cowboy v. Mars Inc. (2008), Manhattan Federal Court In Burck v. Mars Inc, Robert Burck who is well known in the New York City area as “the Naked Cowboy”. This persona is portrayed by his signature cowboy boots, cowboy hat, underwear and his guitar strumming skills. The character is his livelihood and his means of income. Since 1998 he has been strumming through the streets of New York as well as having guest appearances at events ranging from Mardi Gras in New Orleans to music videos and television programs. In 2007 he recorded his first album with JAMBOX recording studios and was featured on MTV news.i The Naked Cowboy has become well known in not only New York City but in the greater United States. Mars Incorporated are the creators and producers of the M&M marketing scheme including the well known M&M’s that take on human personification. Mars Inc. created a short animation of Blue M&M playing a guitar while dressed in a white cowboy hat, cowboy boots and underpants on the electronic animation display that hangs outside the M&M’s store at Times Square, New York. Burck owns the trademarks to the Naked Cowboy name and likeness.ii The defendant clearly has procured Mr. Burck’s livelihood and used it for their financial gain without his permission. It is the intention of the Plaintiff to show that this is a violation of Mr. Burck’s trademark rights and privileges, and an infringement on his rights as a United States citizen. We see from the areas of privacy law including appropriation that it is illegal to appropriate an individual’s name or likeness for commercial or trade purposes without consent. Appropriation is defined as taking a person’s name, picture, photograph or likeness and using it for commercial gain without permission.iii This law has been reformed and defined by way of case law and citations throughout the years. It is with this purpose in mind that examples will be cited. In 1902 Abigail Roberson of Albany New York found her picture placed on posters all over town in advertisements for Franklin Mills Flour Company. In this claim the plaintiff was suing for invasion of privacy. At the time the state’s high court ruled that “the so-called ‘right of privacy’ has not yet found an abiding place in our jurisprudence, and, as we view it, the doctrine cannot now be incorporated without doing violence to settled principles of law by which the profession and the public have long been guided”. This controversial decision from the courts was the beginning of an outcry for the way Ms. Roberson had been treated and as a result the nation’s first privacy laws were adopted.iv Almost sixty years later in the courts more narrowly defined this appropriation and added a precedent to protect the media from such suits. The defendant may attempt to use this precedent to show that their publication is protected. The Booth rule procured from the Booth v. Curtis Publishing Co. states that “the use of a person’s name or likeness in an advertisement for a magazine or a newspaper or a television program is usually not regarded as an appropriation if the photograph or name has been or will be a part of the medium’s news or information content.”v To be protected in this rule the medium would have to show that the procured advertisement appeared in a medium and was republished or re-used for the same intended purpose. It is the plaintiff’s argument that the defendant had no such intent and that the medium in question was produced unlawfully and in violation of privacy laws therefore the Booth rule would not be an applicable defense in the claim. Thirty years later in the White v. Samsung case (1992) Ms. Vanna White brought to court a similar example of appropriation when Samsung Electronics produced a television commercial in which a robot dressed in an evening gown and blonde wig was on a similar set to that of “Wheel of Fortune” and in the footnotes it read “longest running game show, 2012 A.D.” the point was that Samsung products would be around long after Vanna White was replaced by a robot. Even though Samsung did not use Ms. White’s name or exact image, the likeness was unmistakable. Ms. White won her case in the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals which ruled that “The identities of the most popular celebrities are not only the most attractive for advertisers, but the easiest to evoke without resorting to obvious means such as name or likeness or voice”. The ruling was that performers should be protected from exploitation. It was also added to the decision of the courts that to protect the media from appropriation suits, a disclaimer could be added in an advertisement as long as it is prominent in the ad, not just small type on a large page.vi Therefore we see that the defendant has not only infringed upon the Plaintiff’s privacy rights but what’s worse, the whole thing would have been remedied with the simple phone call to acquire consent or a disclaimer placed strategically in the advertisement stating that Mr. Burck has not endorsed M&M’s directly. The Defendants actions are not only a direct violation of the Federal Lanham Act which protects registered trademark rightsvii, But according to Ali v. Playgirl where the courts appropriated a precedent “the right of publicity recognizes the commercial value of the picture or representation of a prominent person or performer, and protects his proprietary interest in the profitability of his public reputation or persona”viii In this regard the Plaintiff must show that he is a prominent figure who is publically recognized. This fact is addressed in his many published and recognized debuts in all different mediums around the country, some of which have been listed earlier in this brief. Mr. Burck has frequently been introduced on television shows, music videos, and events. The Naked Cowboy has not only been prominent in the New York area in which the alleged infringement took place, but has been prominent in a number of different medium. Mr. Burck obtained a trademark on his performing character for purposes of corporate and marketing purposes and owns the trademark rights to the Naked Cowboy’ persona. A trademark by definition is any word, symbol or device-or combination of the three-that differentiates an individual’s or company’s goods and services from the products or services of competitors. By using The Naked Cowboy personification, Mars inc. has infringed upon Mr. Burck’s rights as a trademark owner. Mars Inc. used the image of the naked cowboy for their own trade and financial purposes without first recognizing the ownership of the trademark or acquiring the required permission to do so. It is the Plaintiff’s feeling that the outlined infringements have portrayed him in a false light of endorsement to Mars Incorporated and specifically the M&M’s product without his consent or knowledge. It has been the plaintiff’s suggestion that as his character persona, which has been infringed upon, is in fact his livelihood and means of income, this infringement has a significant impact on his work. It is asked that the defendant take on the responsibility of compensating for the Mr. Burck’s unauthorized services or else retract the said infringing advertisements. i www.biography.com; Robert John Burck CNN News Corporation; iii Don R. Pember Clay Calvert, Mass Media Law iv Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Co., 171 N.Y. 538 (1902) v Boot v. Curtis Publishing Co., 11 N.Y.S. 2d 907 (1962) vi White v. Samsung Electronics America, Inc., 971 F. 2d 1395 (1992); rehearing den. 989F.2d 1512 (1992) vii Don R. Pember Clay Calvert, Mass Media Law; pg.562-567 viii Ali v. Playgirl, Inc., 447 F. Supp. 723 ii Bibliography Secondary Sources: www.CNN.com; The Naked Truth About the Naked Cowboy Case.2008 United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, official published complaint. The New York Post; NY’s Naked Cowboy sues M&Ms maker for $6 million. 2008 The Wall Street Journal; The Naked Cowboy Sues The Naked M&M. 2008 Primary Sources: White v. Samsung Electronics Inc. Don R. Pember Clay Calvert, Mass Media Law Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Co. Booth v. Curtis Publishing Co.