American Bar Association 6th Annual Labor & Employment Law

advertisement

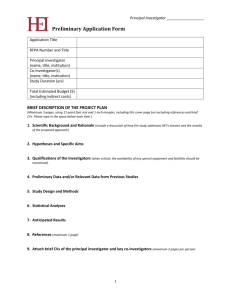

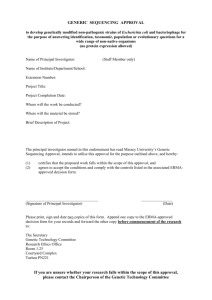

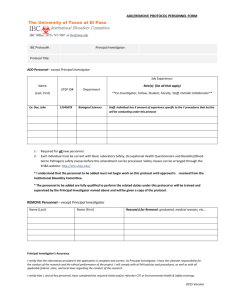

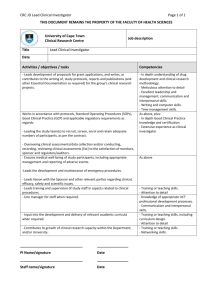

American Bar Association 6th Annual Labor & Employment Law Section Westin Peachtree Plaza, Atlanta, Georgia November 1, 2012 Executive Behavior Run Amok: Ethical and Strategic Considerations for Counsel “Brave” Enough to Step into a High Level Workplace Investigation “Where to Begin: Strategic Considerations on Choosing and Retaining the Investigator and Planning the Investigation” Prepared by: Julie A. Moore, Esq. Employment Practices Group 8 Rice Street, Suite 201 Wellesley, MA 02481 Phone: 978.975.0080 Fax: 978.683.8027 JMoore@EmploymentPG.com www.EmploymentPG.com Employment attorneys are often called upon to oversee and conduct investigations into various forms of employee misconduct, including harassment and discrimination. High level executives often are the persons accused and, in those cases, extra care and discretion are required. The stakes are high, and the investigation must be done right. Part of the employment counsel’s duty is to determine precisely what investigative needs exist, and to provide guidance as to engaging the right investigator, whether that is someone from within the organization or outside. The first question we should ask as attorneys and investigators is why we are considering conducting or overseeing an investigation. Whether conducted in-house by an experienced human resources professional under the guidance of counsel, by the employer’s usual employment counsel, or by an outside investigator (either under the attorney-client privilege cloak or not), the purpose of the investigation is to determine if 1 the allegations raised have merit and, if so, what corrective and/or remedial action should follow. In cases involving top executives, we expect them to be held to the same or higher standard of conduct as compared to other employees. We expect them to be role models of appropriate workplace behavior and can expect criticism if the rules and policies are not applied with equal force when allegations are leveled against them. Dotting the I’s and crossing the T’s, so to speak, is even more critical when the accused is high ranking. In many situations, investigations are legally required and, at other time, are a matter of best practices and necessary internally. Title VII states that employers must “take all steps necessary to prevent harassment from occurring.” Since 1999, the EEOC has also made it clear that employers have an obligation to investigate claims of sexual harassment. In considering the issue of whether the alleged sexual or gender-based conduct was unwelcome, the EEOC’s “Policy Guidance on Current Issues of Sexual Harassment” (available at http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/currentissues.html) N-915050, 3/19/90, considers whether the alleged victim made a contemporaneous complaint, which would be persuasive evidence that the sexual harassment did, in fact, occur. To this end, the EEOC instructs that, “In investigating sexual harassment charges, it is important to develop detailed evidence of the circumstances and nature of any such complaints or protests, whether to the alleged harasser, higher management, co-workers or others.” It is obviously impossible to do this without the investigation that is undertaken being meaningful and thorough in nature. Further elaborating on the duty to investigate in the context of remedial action, the EEOC Guidance proscribes: Since Title VII affords employees the right to work in an environment free from discriminatory intimidation, ridicule, and insult (Vinson, 106 S. Ct. at 2405), an employer is liable for failing to remedy known hostile or offensive work environments. See, e.g., Garziano v. E.I. Dupont de Nemours & Co., 818 F.2d 380, 388, 43 EPD ¶ 37,171 (5th Cir. 1987) (Vinson holds employers have an “affirmative duty to eradicate 'hostile or offensive' work environments”); Bundy v. Jackson, 641 F.2d 934, 947, 24 EPD ¶ 31,439 (D.C. Cir. 1981) (employer violated Title VII by failing to investigate and correct sexual harassment despite notice); Tompkins v. Public Service Electric & Gas Co., 568 F.2d 1044, 1049, 15 EPD 7954 (3d Cir. 1977) (same); Henson v. City of Dundee, 682 F.2d 897, 905, 15 EPD ¶ 32,993 (11th Cir. 1982) (same); Munford v. James T. Barnes & Co., 441 F. Supp. 459, 466 16 EPD ¶ 8233 (E.D. Mich. 1977) (employer has an affirmative duty to investigate complaints of sexual harassment and to deal appropriately with the offending personnel; “failure to investigate gives tactic support to the discrimination because the absence of sanctions encourages abusive behavior”) 2 When an employer receives a complaint or otherwise learns of alleged sexual harassment in the workplace, the employer should investigate promptly and thoroughly. The employer should take immediate and appropriate corrective action by doing whatever is necessary to end the harassment, make the victim whole by restoring lost employment benefits or opportunities, and prevent the misconduct from recurring. Disciplinary action against the offending supervisor or employee, ranging from reprimand to discharge, may be necessary. Generally, the corrective action should reflect the severity of the conduct. See Waltman v. International Paper Co., 875 F.2d at 479 (appropriateness of remedial action will depend on the severity and persistence of the harassment and the effectiveness of any initial remedial steps). Dornhecker v. Malibu Grand Prix Corp., 828 F.2d 307, 309-10, 44 EPD ¶ 37,557 (5th Cir. 1987) (the employer's remedy may be “assessed proportionately to the seriousness of the offense”). The employer should make follow-up inquiries to ensure the harassment has not resumed and the victim has not suffered retaliation. See also Watson v. Blue Circle, Inc., 324 F.3d 1252 (11th Cir. 2003) (in which issues of adequacy of investigation of harassment complaints by female cement truck driver resulting in reversal of district court’s summary judgment in favor of defendant employer); Hatley v. Hilton Hotels Corp., 308 F.3d 473 (5th Cir. 2002) (employer’s investigation of plaintiff’s complaints of harassment deemed insufficient to overcome having ignored similar, past complaints, resulting in appellate court’s refusal to overturn jury award for plaintiff); Malik v. Carrier Corp., 202 F.3d 97 (2d Cir. 2000) (holding that employer’s investigation of sexual harassment complaint is required by law). EEOC regulations are also a resource on an employer’s duty to promptly investigate allegations of sexual harassment. 29 C.F.R. Sect. 1604.11(d) (“With respect to conduct between fellow employees, an employer is responsible for acts of sexual harassment in the workplace where the employer ... knows or should have known of the conduct, unless it can show that it took prompt immediate and appropriate corrective action.”) See also Crawford v. Metro. Gov’t of Nashville & Davidson Cty, Tenn., 555 U.S. 271, 278 (2009) (Employers are… subject to a strong inducement to ferret out and put a stop to any discriminatory activity in their operations as a way to break the circuit of imputed liability”). Once it has been determined that an investigation is needed, a plan needs to be implemented. The first consideration is who the appropriate person is to act as investigator. This paper will address how to get started in an investigation, which includes selecting the right person to investigate, documenting that retention to include the scope of services to be provided, and considering interim measures to take. Initial considerations also extend to strategizing and planning the investigation, to include issues such as creating and maintaining a file, ensuring that confidentiality is maintained to the greatest extent practicable, coordinating with a point person within the organization to facilitate logistics and process issues, identifying documents and other potential evidence 3 to gather or preserve, and notifying those involved and potential witnesses of their anticipated involvement and expected cooperation. Promptness is a cornerstone of getting started in an investigation. The EEOC’s "Enforcement Guidance: Vicarious Employer Liability for Unlawful Harassment by Supervisors," (available at http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/harassment.html), 915.002, 6/18/99 ("Guidance") is an excellent resource for investigators. The Guidance states that fact-finding investigations must be launched "immediately," relying on the following case law: Van Zant v. KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, 80 F.3d 708, 715 (2d Cir. 1996) (employer’s response prompt where it began investigation on the day that complaint was made, conducted interviews within two days, and fired the harasser within ten days); Steiner v. Showboat Operating Co., 25 F.3d 1459, 1464 (9th Cir. 1994) (employer’s response to complaints inadequate despite eventual discharge of harasser where it did not seriously investigate or strongly reprimand supervisor until after plaintiff filed charge with state FEP agency), cert. denied, 513 U.S. 1082 (1995); Saxton v. AT&T, 10 F.3d 526, 535 (7th Cir 1993) (investigation prompt where it was begun one day after complaint and a detailed report was completed two weeks later); Nash v. Electrospace Systems, Inc. 9 F.3d 401, 404 (5th Cir. 1993) (prompt investigation completed within one week); Juarez v. Ameritech Mobile Communications, Inc., 957 F.2d 317, 319 (7th Cir. 1992) (adequate investigation completed within four days). The amount of time it takes to conclude the investigation, however, necessarily depends on the particular circumstances, such as the number of people involved, the extent of the allegations, etc. A. Selecting the Investigator Determining who should investigate the complaint is the primary consideration an employer must make at this juncture, after being notified of a possible violation of policy. The key factors to consider in selecting an appropriate investigator are experience and objectivity. The employer may have someone from within the organization conduct the investigation or someone from outside the organization. Advantages and disadvantages exist with both options. Under federal civil rights law, an employer is exposed to liability where it fails to investigate or fails to properly investigate a discrimination complaint. A recent Massachusetts federal court case clearly illustrates the importance of selecting an appropriate investigator as part of that proper investigation. In McLaughlin v. National Grid USA, 2010 WL 137814 (D. Mass. 2010), the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts examined the claims of the plaintiff, Manch McLaughlin, that National Grid retaliated against him by conducting a sham investigation after he filed an internal complaint of racial harassment. Mr. McLaughlin, who is African-American, had been a National Grid employee for thirty (30) years. In 2005, National Grid posted a position for a Gas Operations Supervisor in Glen Falls, New York, and Mr. McLaughlin applied. Of the candidates interviewed, Mr. McLaughlin was ranked the lowest. A Caucasian man was selected for the position instead. Mr. McLaughlin was advised that he was not selected due to his lack of 4 experience and his poor performance during the interview process and, as expected, he disagreed. A couple of months later, National Grid posted two additional open Gas Operations Supervisor positions in another New York location, for which Mr. McLaughlin again applied. This time, Mr. McLaughlin was not even selected for an interview. The company hired two Caucasian employees to fill those slots. The company maintained that the individuals who were selected were more qualified than Mr. McLaughlin. Once again, Mr. McLaughlin challenged the company’s choices, asserting that he was equally, if not more, qualified for the positions than those who were selected, and, at the very least, possessed the necessary qualifications to be granted an interview. Subsequently, Mr. McLaughlin filed a complaint with the Human Resources Department concerning the company’s decision not to interview him for the three (3) positions he had sought. He sent a letter to Wanda Grace, the Manager of Labor Relations, outlining his concerns. Ms. Grace, together with Dennis Flood in Human Resources, was the investigator. Mr. McLaughlin was troubled that Mr. Flood participated in the decision not to hire him for the Glens Falls job, thus felt it was wrong that he was involved in the investigation that followed. It is unclear if he voiced his concerns at the time the investigation commenced or just after the fact; the company’s records of its investigation were incomplete. In addition, at the close of the investigation, Ms. Grace and Mr. Flood met with Mr. McLaughlin and, according to Mr. McLaughlin, Ms. Grace (who is African American) began the meeting by saying, “Mr. McLaughlin, I’m just gonna tell it to you like it is…. Every time black people don’t get the position that they think they deserve, the first thing they cry is discrimination.” Though Ms. Grace essentially admits to making such a statement, she denies any negative implications. Mr. McLaughlin filed a charge of discrimination with the EEOC, and an integral part of the charge was that the investigation was an independent discriminatory act under Title VII and Section 1981. Interestingly, National Grid did not argue during litigation that a sham investigation cannot qualify as an adverse employment action. Mr. McLaughlin’s claim was premised on two central facts: (1) that Dennis Flood was an inappropriate choice as investigator, as an alleged conflict of interest existed because Mr. Flood has already been involved in the decision not to hire Mr. McLaughlin for the Glens Falls job, and (2) Ms. Grace’s statement that black people “cry” discrimination when they don’t get positions that they think they deserve. Mr. McLaughlin asserted that these facts evidenced bias on the company's part. Mr. McLaughlin subsequently filed his complaint in federal court, and National Grid moved for summary judgment. The court stated, “A jury might reasonably infer that an investigation was not independent or valid if it were conducted by a person who participated in one of the challenged decisions.” Moreover, the court found that Ms. Grace's comments could be problematic, even if an “innocent explanation” existed. As a result, the court ruled that Mr. McLaughlin was entitled to a trial on this portion of his 5 discrimination claim (and dismissed on summary judgment the remaining failure-topromote claims). See also Bernstein v. Board of Educ. of School Dist. 200, 191 F.3d 455 (7th Cir. 1999) (employer’s failure to investigate workplace harassment claim can form the basis for Title VII discrimination suit). His retaliation claim also survived summary disposition. The Massachusetts court found unpersuasive National Grid’s argument that it followed its regular policies and procedures and, further, that it was appropriate to utilize Dennis Flood because he had experience in investigating complaints. The company had relied on the decision of Azimi v. Jordan’s Meats, Inc., 456 F.3d 228, 246 (1st Cir. 2006), for the proposition that an employer is not liable for discrimination where the investigation was reasonable, the employer heard the complaining party’s side of the story, and the employer determined that the accused harasser was more credible. The underlying legal briefs filed by Mr. McLaughlin proved interesting, as he had argued that the investigation was “fraudulent,” that Ms. Grace and Mr. Flood were “incompetent” investigators, and that Mr. Flood’s role in investigating was “the equivalent of demanding that [he] find himself guilty of discriminatory activities.” Calling it a “ruse,” Mr. McLaughlin criticized National Grid for failing to expend the “time, manpower, or risk of an adverse finding that a legitimate investigation would have entailed.” Lessons learned from this case are obvious to the seasoned investigator, but many large national companies like National Grid still fail to understand the importance of choosing the proper investigator at the outset of an investigation. An employer should ensure that both the accused and accuser(s) have no credible reason to believe that the investigator cannot carry out his or her responsibilities in a fair and objective manner. 1. Selecting an In-House Investigator In most cases, having an employee of the organization investigate, such as a human resources representative, general counsel or senior manager, can provide several advantages. The person, first of all, is already aware of the organization’s business and may have some understanding of the parties involved. The person should be intimately familiar with organization policies and procedures that need to be followed. The person is on-site and, depending on other priorities and schedules, may be available to commence the fact-finding right away. There are disadvantages, however. If an in-house employee investigates, the person must possess the necessary skills, attributes and objectivity in order to ensure a fair investigation. Reporting relationships, biases and personal relationships must be examined. Where the person accused is a high ranking executive, this issue becomes critically important. The investigator must truly be neutral and, as important, the complaining party and the person accused must also perceive that neutrality exists. Further, the investigator must be perceived as someone who can competently and equitably interview witnesses and reach appropriate factual 6 conclusions. Clearly, selecting an individual who has a vested interest in the outcome of the investigation is ill advised. The in-house investigator must possess training and experience to investigate. If the person has not received any training on how to conduct an investigation, that is problematic. Investigations are complex and must be conducted the proper way, as dictated by various case law, EEOC guidance and other regulations. If the investigator makes inappropriate comments during the investigation, fails to give appropriate warnings, such as against retaliation, or omits certain assurances, such as confidentiality to the extent possible, the investigation will be compromised. Finally, the investigator must be able to conduct the investigation promptly. Accordingly, the investigator must essentially “drop everything” in order to interview witnesses and find out what actually occurred. The investigation must be the priority for the investigator. 2. Selecting a Third Party Investigator In many situations, employers properly choose to use a person from outside the organization to investigate the complaint. When the complaint is against a high level executive or when the allegations are complex or have significant legal consequences, an outside investigator is often the best choice. Legal consultants, human resource consultants and even legal counsel are often asked to act as investigators. Many advantages exist for using an outsider. First, assuming there is no conflict of interest or prior relationship of any significance, the outside investigator will be perceived to be completely independent and unbiased. Also, the investigator chosen will have particular expertise and experience in conducting investigations, so that the proper questions will be asked and other pertinent information sought. With an experienced investigation, the record created and any report generated often is often of a higher quality and will assist in risk-management efforts, should any litigation follow. The investigator should be well poised to testify in court and otherwise reflect the professionalism and show that the investigation complied with reasonable industry standards. With the high level executive, traits especially important in the investigator are confidence and the ability to take control and lead the interview. Executives are used to being in charge and leading meetings. In an investigation, however, it is the investigator who sets the tone and controls the questioning. The investigator cannot be timid. B. The Retention Letter Where an outside investigator is retained, the investigator and the organization should articulate the parameters of the investigation. The issues to address include the investigator’s role as a factfinder, and one who may be charged with making decisions as to whether a statute or the organization's policies or practices have been violated and 7 making recommendations as to corrective or remedial measures. The letter should outline the tasks that the investigator will undertake. Issues of confidentiality, indemnification, work product and attorney-client privilege should be discussed and agreed upon, as should the investigator’s fees and related costs, the investigator’s participation in the event of litigation, the internal contact person within the organization, and the individual(s) to whom the investigative report, if requested, should be addressed. All of these details should be committed to writing in the retention letter. Examples of engagement letters are attached as Exhibit A. 1. Investigator’s Role and Scope of Services The retention letter should clearly articulate the investigator’s primary role in the investigation as a fact finder, and also make clear whether it will be the role of the investigator or the employer to make decisions as to whether statute or the organization's policies or practices have been violated. Where investigating a harassment case, for example, the investigator must make clear that he or she will not offer any legal conclusions as to whether a hostile environment existed or whether sexual harassment had otherwise taken place. The letter should also clearly state whether the investigator’s role will include making recommendations regarding corrective or remedial measures, where appropriate. Examples of measures that employers may utilize to stop harassment or other inappropriate workplace conduct and to ensure that it does not occur include verbal or written warning or reprimand; transfer or reassignment; demotion, suspension or discharge; reduction of wages; training or counseling of the harasser to ensure that he or she understands why his or her conduct violated the employer’s anti-harassment policy; and monitoring of the harasser to ensure that the harassment has ceased. Other measures may be called upon to rectify the negative effects of harassment, if that is in issue, including restoration of leave taken because of the harassment; expungement of negative evaluation(s) in an employee’s personnel file that arose from the harassment; reinstatement; an apology by the harasser; monitoring treatment of employee to ensure that he or she is not subjected to retaliation by the harasser or others in the workplace because of the complaint; and correction of any other harm caused by the harassment (e.g., compensation for losses). The retention letter should also address the issue of confidentiality. It should state that the investigation will be kept as confidential as possible, due to the sensitivity of topics that will likely arise and relationships at issue. Given the recent NLRB decision of Banner Health System d/b/a Banner Estrella Medical Center and James A. Navarro, Case 28-CA-023438, 358 NLRB No. 93 (July 30, 2012), the investigator and employer must carefully consider what is said to interviewees about confidentiality. Where the investigator’s communications are directed to the employer’s legal counsel, the retention letter should specify that such communications will be protected under the attorney-client privilege. If the investigator is performing his or her 8 investigative duties as an attorney, the retention letter should specify that all communications, work product, and the final investigative report will be protected from disclosure pursuant to the attorney-client privilege, unless waived by the client. The letter should state that the investigator will strive to conduct and conclude the investigation as promptly as possible, and should also address the possibility that information regarding other possible inappropriate workplace conduct, or supervisors’ response to such conduct, may come to light during the course an investigation. While this information may not have been part of the initial allegations made by the complaining employee, it may nevertheless become relevant to the investigation (a situation sometimes referred to as “issue creep”). An example of this can be seen in a sexual harassment investigation, where Employee A alleges that he was sexually harassed by Employee B. During the investigation, the investigator learns from three (3) other employees who are interviewed that they also claim to have been harassed by Employee B and, in fact, told their supervisors, but nothing was done to stop the harassment. The investigator should always anticipate that the direction of the investigation may need to be adjusted or revised as the investigation progresses. Open communication must be maintained throughout the process. The retention letter should also memorialize the parties’ agreement that the investigator will exercise his or her independent judgment to make whatever findings the investigator deems warranted based on the evidence developed in the investigation. Further, it should state that the parties’ agreement as set forth in the retention letter is not dependent on the investigator making or failing to make any particular credibility determination, finding of fact, or conclusion. The letter should also state that the investigator is unaware of any conflicts of interest based on the information provided, and require that the organization immediately notify the investigator if it later learns of any additional parties with an interest in the matter being investigated so that the investigator may ensure that no conflict of interest arises. 2. List of Tasks to be Undertaken By Investigator Some investigators and clients prefer to articulate in the engagement letter the particular tasks contemplated and agreed on, making specific reference to the relevant documentation and information - and that the investigator is granted access to all of it. This may include the following: Review all pertinent correspondence, notes, complaints, etc. that relate to the allegations of inappropriate behavior. Review relevant policies and procedures. Review relevant personnel documents and other employment records, as appropriate. 9 Interview the complaining employee(s) and those accused of inappropriate workplace conduct, as well as interview employees or witnesses who have knowledge of the allegations, the defense, or any possible motive. Identify and ascertain any other corroborating evidence to assist in the factfinding process. Evaluate and resolve conflicting factual information. Draft a summary of each witness interview, if requested. Prepare a written report of investigative findings, which may include the following information: o A statement of the allegations and identification of documents reviewed and witnesses interviewed. o Statement of any defenses, denials, and other relevant information learned. o Factual findings supporting each issue. o Identification of any conflicting factual information. o The factual conclusions reached after resolving any credibility issues. Provide a determination as to any policy or statutory violations, if requested. Provide recommendations pertaining to corrective or remedial action, if requested and appropriate. 3. Costs, Fees and Indemnification The letter should memorialize the parties’ understanding that payment for the investigator’s services and expenses is in no way contingent upon the outcome of the investigation. It should also set forth the agreed upon fee, whether flat fee or an hourly rate, and specify any retainer to be paid to the investigator. Where the parties have agreed upon an hourly rate arrangement, the letter should enumerate the types of the investigator’s services for which time will be charged, such as time spent interviewing witnesses, writing the report of the findings, performing any necessary research, as well as time spent on telephone calls relating to the investigation, including calls with the employer, witnesses, potential witnesses, or counsel representing any of the parties. A separate hourly rate may be charged for travel time, and this should be specified in the letter as well. 10 In the event of a flat fee arrangement, the letter should state that the fee contemplates the completion of the tasks outlined therein, and articulate the parties’ agreement to communicate closely throughout the investigation and, if the scope of the work far exceeds what was discussed, to revisit the fee arrangement. The letter should also set forth the fee arrangement for any time spent by the investigator preparing for and attending any depositions and providing testimony at any administrative agency or court. It should further specify the employer’s agreement to provide a defense and indemnification to the investigator and his or her business entity in the event he, she or it is named as a respondent or defendant in any legal proceeding that stems from the investigation. The letter should memorialize an agreement to pay the investigator the then current hourly rate for all time spent in connection with any such litigation, including but not limited to time spent at a deposition or testifying at trial. Investigators may also want to add a provision that an investigator's attorney’s fees are covered if the investigator is later sued. In addition to addressing fees, the letter should memorialize the client’s agreement to reimburse the investigator for costs and expenses he or she may incur in the course of the investigation, such as for long distance telephone charges, courier and other delivery fees, postage, photocopying and other reproduction costs, and travel costs such as mileage reimbursement and parking. C. Strategizing and Planning the Investigation Conducting internal investigations is a delicate matter, particularly involving top executives. In many cases, legal counsel should be consulted upon receipt of the complaint to ensure that the investigation is being handled, from the outset, pursuant to organization policy, following all legal guidelines and regulations, and consistent with industry standards. Because the stakes can be high when an employer is called to investigate claims of harassment and other suspected misconduct, such as theft or discrimination, the utmost care must be given at all times. The investigator should assess the situation and prepare a strategy for conducting an investigation as promptly as possible. The investigation must keep in mind that the investigation must be conducted consistent with any particular statutes and collective bargaining agreements, as well as internal policies and procedures. Following policies is critical. For example, in Madeja v. MPB Corp. d/b/a Split Ballbearing, 149 NH 371 (2003), the New Hampshire Supreme Court ruled that there was evidence from which a reasonable jury could have found that the defendant’s investigation and remedy were neither reasonable nor adequate under the circumstances, stating: There was also evidence that despite the defendant’s policy requiring human resources involvement in all sexual harassment complaints, human resources was never contacted regarding the 11 plaintiff’s complaint. Although [Manager #1] testified that he and [Manager #2] discussed the plaintiff’s complaint with [HR], [HR] testified that he had no recollection of these discussions. [Manager #3] testified that human resources never contacted him about the plaintiff’s complaint. Clearly, courts emphasize the importance of an employer following the letter and spirit of any policy that it maintains surrounding investigating complaints. 1. Considering and Implementing Interim Measures The EEOC's Guidance relating to sexual harassment advises employers that it may be necessary to undertake interim measures at the outset of an investigation to ensure that further harassment does not occur. The same type of interim measures may be taken regarding other forms of harassment, discrimination and similar misconduct. Accordingly, the investigative plan should commence by determining if such interim steps are necessary. The purpose is to ensure that the complaining party is protected from continued exposure to possible inappropriate behavior and retaliation. Fears of retaliation usually run deeper when the accused is a high ranking executive, given the power that he or she wields, which can affect job security and terms or conditions of employment. The complaining party and witnesses naturally can be fearful of participating in such a highstakes investigation. An employer should carefully consider the steps to take, ensuring that the rights of all involved are taken into account. Factors to be considered in determining whether interim measures are needed include, but are not limited to, the following: the expressed wishes of the complainant; the nature and extent of the allegations; the personal safety of the complainant; the number of complainants; whether the alleged wrongdoing is of an ongoing nature; the behavior of the alleged wrongdoer; and whether the accused wrongdoer has an alleged or actual history of engaging in misconduct. If, based on a review of this information, the employer determines that interim action is advisable, the approach most often utilized is to separate the employees. In short, the following options should be on the table: Placing the alleged wrongdoer on administrative leave; Placing the complaining party on administrative leave, if requested; 12 Transferring the alleged wrongdoer, or the complainant if he or she requests, to a different area/department or shift so that there is no further business/social contact between the two; Instructing the alleged wrongdoer to stop the complained-of conduct; and Eliminating the alleged wrongdoer's supervisory authority over the complainant. Where the employees work in the same location and it would not be possible to accomplish a separation by re-assignment, consideration should be given to placing the accused employee on paid or unpaid suspension and removed from the premises, pending the outcome of the investigation. This can be complicated, however, with a high-ranking executive. A careful balance must take place so that business is not unnecessarily interrupted. Supervisory staff should be notified of the importance of protecting the complaining employee from possible retaliation. Where the complaining party leaves the workplace on his or her own volition and expresses a desire to stay away from the site until the situation can be resolved, he or she should be placed on paid leave of absence pending the outcome of the investigation. This is not the best option and should be used only in situations where the complaining employee expresses a desire and/or has a compelling reason to remain away from the site pending the investigation. Another situation in which such an interim measure may be appropriate is where stalking, violence or threats of violence have been alleged, or where there are other indications that the accused employee may be mentally unstable. In these cases, the complaining employee may be offered a brief temporary assignment in another business location, or time off with pay. As a general matter, however, an employer’s removal of any individual from the workplace pending completion of the investigation should be limited to the individual accused of serious misconduct. In all instances, supervisory/management staff must be reminded of the organization’s zero-tolerance policy against retaliation of any kind and advised to take all possible steps to avoid retaliatory conduct. Care should be taken not to harm or penalize in any way the complaining party, so long as the complaint is believed to be made in good faith. Simultaneously, the accused’s rights must be respected. No presumption whatsoever should be made at the outset of an investigation that a policy violation or other misconduct has occurred. 13 2. Creating and Maintaining a File The investigator should create and maintain a confidential investigative file, such as a binder or redwell, separate from personnel files. The file should allow for one central place to keep organized all documents and other materials related to the investigation. This may include but not be limited to interview notes, relevant employment documents, journals, recordings, photographs, voice mails, e-mails, telephone records, or other items pertaining to the allegations or the investigation into them. 3. Ensuring that Confidentiality Is Maintained to the Greatest Extent Practicable The employer should ensure that the investigation is kept as confidential as possible, by communicating information about the investigation only to those who need to know about it. An employer should not promise absolute confidentiality to the complainant, the alleged wrongdoer or other witnesses, because such a promise may obstruct the employer's ability to conduct a fair and thorough investigation. Generally, the complainant and the alleged wrongdoer should be kept informed of the status of the investigation during the process. 4. Coordinating with a Point Person within the Organization to Facilitate Logistics and Process Issues The employer, perhaps in conjunction with the investigator, should determine who from the organization will act as a point person to assist in the coordination of witness interviews and assembly of any additional information that may be needed as the investigation continues. Issues such as where, when, in what order, and the like must be discussed. The organization and investigator should caucus as to whether it is advisable to have a third party present for any or all witness interviews. Union and collective bargaining issues must be considered as well. 5. Identifying Documents and Other Potential Evidence to Preserve The organization may see the immediate need to take steps to preserve evidence. For example, the organization may determine that emails or other electronic evidence will need to be saved and preserved. Consideration at the outset of an investigation of these issues is critically important. 6. Gathering Preliminary Information Human resources is often the key conduit of information to the investigator. Others may play a role as well. The investigator should receive as much information as 14 possible by the supervisor or manager who reported the matter, from the complaining party, or from any other third party who made the complaint known. Initial inquiries must focus on the identities of the alleged victim, the complaining party, if different, the accused, and any witnesses or others who may have knowledge of the alleged improprieties or any defenses. The investigator may also likely be in contact with members of the executive team or other managers or supervisors to obtain relevant background information. Sometimes the Board of Directors of General Counsel is involved in cases against high level executives. Background information about the professional and personal relationships, if any, should be gathered. 7. Contacting the Complaining Party and Alleged Wrongdoer The employer or investigator should contact the complaining party and advise that an investigation will be conducted by the investigator, that the complaint is being taken seriously, that misconduct in the workplace is not tolerated, and that he or she will be interviewed in short order. The organization should ask for the complaining party's cooperation, emphasize confidentiality consistent with the law, and articulate its policy of non-retaliation against employees who participate in a workplace investigation. A similar communication should be made with the person accused, advising that a complaint has been made and that an investigation will be underway. Similar admonishments about cooperation, confidentiality (consistent with the law) and nonretaliation should be given. Reference to internal policies should be made as well. The timing of when to tell the accused executive will be fact dependent and should involve a careful assessment of the circumstances. Arrangements should be made then, if possible, to schedule the witness interview. If not, the investigator should advise that he or she will be back in touch shortly to schedule meetings. 8. Reviewing Materials Next, the investigator should review any documentary evidence or other materials that may exist. This includes relevant documents from the personnel files of the complaining party and accused; any notes or writings prepared by any supervisor or manager about the incident; documents, emails, graffiti, offensive material or tangible evidence of any kind that may pertain to the allegations or defenses; and any harassment complaint form or other written complaint of the complaining party that may exist. The investigator should also verify that any offending material had been removed or permanently covered up. A review of materials may also include organization or hierarchy charts, workforce profiles, comparator information, payroll records, time cards or time sheets, training records and related documentation, phone records, emails, and voicemails. Safeguarding potential evidence to prevent any spoliation issues is critical. 15 9. Preparing for Witness Interviews Preparation for witness interviews is now underway. Based on the information received to date, the investigator should begin to draft witness outlines. Next, a location should be identified as to where witness interviews should be conducted, with consideration given to preserving confidentiality of all involved and ensuring that witnesses feel at ease to speak. It is crucial to plan ahead to ensure a comfortable, nonintimidating environment for interviews that will facilitate communication between the investigator and the person being interviewed. Where the investigation requires interviewing employees at multiple business locations, the investigator should discuss with the employer whether he or she will travel to satellite locations to conduct interviews, or whether all interviews will be held at headquarters. The latter arrangement may require some employees to travel and thus spend more time away from their desks. Whether meeting at a single or multiple locations, avoid meeting in the office of the person being interviewed, or in the office of a high-level executive. Instead, choose a quiet conference room or consider meeting at a nearby off-site location for privacy. Most individuals, even if they are amenable to being interviewed, would rather avoid having their co-workers see them or hear what is taking place. Consider making arrangements to set up the interview room so that it resembles a regular business meeting, perhaps including a beverage and a light snack. Also consider seating arrangements, which can determined whether the person interviewed feels at ease rather than intimidated or “boxed in.” Some investigators prefer to tape record each interview and have it transcribed. If so, ensure that working equipment is available. Special issues can arise as well. Accommodating an individual with a disability may be needed. Also, an investigator may anticipate interviewing individuals for whom English is not their primary language. In that case, the services of a certified translator should be secured. The same criteria that the employer should apply in selecting an investigator-- experience and objectivity-- should be applied when selecting a translator. As a cost savings measure, the organization may offer to have present at the interview a bilingual employee who is conversant in English and the language spoken by the interviewee. This is not recommended, however. By hiring an experienced, objective translator, the investigator ensures that the translator is furthering the organization's interest in conducting a thorough and objective investigation. By relying on the interpretative skills of a fellow employee or internal representative, the investigator relinquishes necessary control over the interview and the accuracy and thoroughness of the information gleaned from it. "Where to Begin” entails quite a bit of work, and being knowledgeable about the issues as well as being organized, practical, and flexible are key. 16