4. Souris Valley Plains - A History

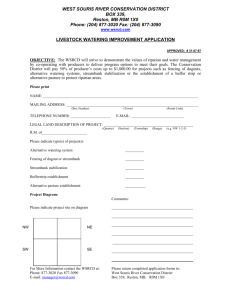

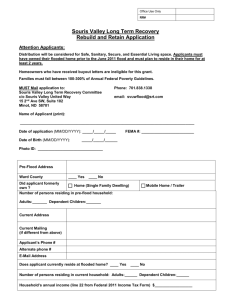

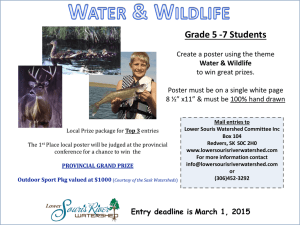

advertisement