Marketing Cost & Margins

advertisement

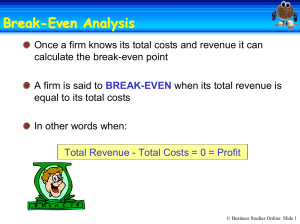

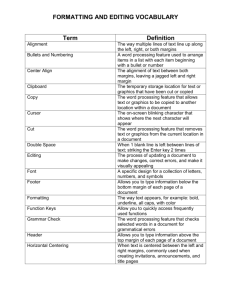

AGEC 6013 WEEK 6 Lecture Notes MARKETING COSTS AND MARGINS FOR AGRIC PRODUCTS High retail prices have always been attributed to excessive profits, unnecessary services and high marketing costs. The Food Marketing Margin (FMM) Consumer food expenditure (or food bill) comprise of marketing components and farm components. Changes in these marketing and farm ‘shares’ of the food bill indicates the trends in costs, profits and services provided by farmers and food marketing firms as well as the performance of the farm sector compared to the food marketing sector. The proportion of the consumer expenditure that goes to the food marketing firms is referred to as Marketing Margin. i. Theoretical Concept of Marketing Margins Marketing margin may be defined in 2 ways: (1) as the differences between consumer retail price and what farmers receive; (2) as the price of marketing services provided. 1. Price Difference Between Two Marketing Stages: The difference between what the consumer pays for food and what the farmer receives - i.e. a marketing margin is simply the difference between the primary and derived demand curves for a particular product. Primary demand is determined by the response of the ultimate consumers and this is usually based on the retail price and quantity purchased by consumers. Primary demand is in some sense a joint demand for all the inputs in the final product. Thus a food product at the retail (i.e. the primary demand) may be divided into two inputs: the farm-based components and the processing-marketing components. The derived demand for the farm product can be obtained by subtracting the cost of all marketing components from the primary demand (i.e. DD = PD - MC). It can therefore be seen that the farm level function or primary supply (PS) represents the derived demand for the farm component of the final product (DD). Thus the derived demand is based on price-quantity relations that exist either at the point where products leave the farm or at intermediate point, where they are purchased by wholesalers or processors. The primary supply (PS ) represents the price-quantity relationship at the producer level. The derived supply (DS) at the retail level is derived from the primary supply (PS ) by adding an appropriate margin. Thus, a retail price is established at the point where the primary demand (PD) intersects the derived supply (DS) as shown in the figure. DS The farm-level price is Price PS based on derived demand (DD) Retail PR and primary supply (PS ). The difference in the two Margin prices is the marketing Farm PF margin or Absolute PD Marketing Margin: M= PR - PF DD Q0 Quantity Absolute Marketing Margin (AMM): This is the gap between prices at different marketing PR levels (farmers, wholesalers, retailers). Thus M2 M1= PR - PF is AMM at farmer level PW M2= PR - PW is AMM at retail level M3 M3= PW - PF is AMM at wholesale level PF C B A DR DW Relative Marketing Margin (RMM) DF It is the ratio of AMM to price at which the product is bought. RMM = AMM/ PB. Qd The relative margin from farmer to retailer is RMMFR = M1/ PR. Gross Marketing Margin This is obtained by multiplying the AMM by the quantity marketed. GMM is represented by area PFAC PR or GMM= Qd (PR - PF ). Net Marketing Margin (NMM) Here the concept takes account of fixed cost, taxes and subsidies - i.e. NMM = GMM - FC - T + S 2. Differences in Prices Due to Cost of Services: The marketing margin may also be defined as the price or cost marketing services. Marketing costs are the return to factors in the marketing process: profits, wages, interest rents. The marketing services include items such as assembly, processing, transportation and retailing. These services are the time, place, form utilities provided by the marketing system. That is, the marketing margin is the price of all utility added by marketing firms, and this price includes marketing firm’s expenses and profits. The supply relation for these marketing services is defined in terms of the marginal cost curve for the services, which in turn depends on input prices. However, marketing services also have demand relation. A marketing margin will thus depend on the particular demand and supply relations for the services, and in this regard, changes in margins may be the result of shits in the supply or demand relations for services as shown in the figure below. The demand curve D is the Margin market demand for services; the supply S2 for services are S1 and S2. As a result of S1 higher input prices, or service prices, M2 marketing margins will increase from M1 M1 to M2 and quantity of services purchase by consumers will decrease from Q1 to Q2. D Pdn cost has fallen, while marketing costs have increased over the past1/4 century due to: 1. Pdn is more specialized in location - fall in pdn Q2 Q1 Cost but increases transport cost. Quantity of services/unit time 2. Away from home eating increases mkg cost. B. The Food Marketing Bill i. Marketing Bill Measurement: Marketing bill is based on costs of all marketing services. It is the difference between national consumer expenditure for all domestically produced food products and what the farmers receive for the same products. Thus the marketing bill is calculated annually and serves as a measure of marketing margin. In the 1990’s about 75% of total national consumer expenditure Consumer of food products went to marketing firms while 25% Expenditure went to farmers. That is, farmers receive 25% of consumer food expenditure , whereas food marketing 200 firms receive 75%. To many, this ratio of 75:25 seem both unfair and an underestimation of the contribution 150 Marketing that agriculture makes to society. But the fact is, the Margin 100 marketing bill does not tell us nothing about the 50 LEVEL of farm prices or the marketing margin, nor is Farm Value it an indicator of costs or efficiency in either the farm 1986 1990 1994 or marketing sector. We need more information to evaluate the marketing bill in order to determine whether it is ‘fair’ or not. ii. Evaluation of the Marketing Bill: The first systematic approach to evaluate the Food Marketing Margin was undertaken in USA in 1921 in order to understand the origins of price differences at consumer and farmer levels. An inference of FMM analysis over the years is that food marketing margin increases as income increases. But as FMM has increased gradually from 68.1% in 1968 to 80% in the 1990s, farm share has decreased gradually from 32% in 1968 to about below 22% in the 1990s. The food marketing bill has been increasing steadily since 1968. The major factors for such an increase are: 1. Population Growth: As a result of population growth, the quantity of food that is marketed has increased, raising the total expenses of food. 2. Cost of Food Marketing Inputs: Rising labor and energy costs in food marketing have added to the rising cost of marketing food. 3. Rise in Food Services: Consumers desires for more marketing services (e.g. convenient foods) have further increased the food marketing bill iii. Cost Components of the Marketing Bill The cost component is also important in evaluating the marketing bill. Some of these costs are labor, packaging, transportation, profits, energy and ads. 1. Labor Costs: Labor cost has been the large component of the food marketing bill in the 1980s and 1990s. It currently represent over 45% of the food marketing bill. These include wages, employment benefits, earnings of proprietors etc.. Wage rates in food marketing have for example increased steadily over the years. a. Food marketing bill closely follows the rate of increase in labor cost. b.Rising labor costs have forced marketing firms to improve operational efficiency by substituting machinery for labor especially in processing (labor saving) 2. Profits in Marketing: The profit portion of the FMB is very controversial. Businessmen see profit as a reward for efficient behavior, and profit is a force for seeking low cost operations and improved products. But economists view profit as another cost of doing business. The fact is where profits result from monopolistic or anticompetitive behavior, the corrective action is justified. Profits in the food marketing industry have been rising over the years. Profits as percentage of shareholders equity has also risen from 8% in the 1950s to 16% in the 1990s. This has attracted capital into the food industry and therefore improved plant and marketing efficiencies. However, profit rates for different industries depend on their competitive structure and degree of product differentiation. For example, historically, sugar, meat, edible oil, milk and grain mill processors have had lower profits than foods breakfast cereals and beverages. Profits can not easily be used as indicator of market performance. Although high or rising profits may reflect superior management or efficient operations, high profits may also result from such market imperfections as concentration, product differentiation and barriers to entry. C. The Farmers Share The difference between the retail price of food and the marketing margin is the FARMER’S SHARE. This is the proportion of consumer’s food dollar that the farmers receive. There are 2 ways of measuring the farmer’s share: i. Marketing Bill Approach: Calculates farmer’s share as a ratio of the farm value of all domestically produced farm foods to the dollar value of consumers expenditures. e.g. In 1986 consumers spent $361 billion on food produced domestically. Farmers received $86 billion, so farmers share was 25%. ii. Market Basket Approach: Is calculated by taking the ratio of the farm value of 74 domestically produced food items to their retail food value. e.g. In 1987, the market basket of the 74-items cost the average family $3,125 and the farm value was $938. the farmer’s share is 30%. The market basket approach generally yield higher farmer’s share than the Marketing Bill Approach. D. Farmer’s share By Commodity The farmer’s share varies from commodity to commodity, depending on the amount of form, place and time utility added by the farmer and the marketing firm respectively. Commodities for which the farmer provides most of the value-added utilities have a higher farmer’s share and those on which the marketing firm provides large share of the utility have smaller farmer’s share. Therefore farm products marketed directly to the consumers in relatively unprocessed or fresh form have higher farmer’s share than those processed. For this reason, animal products tend to have higher farmer’s share than crops. Similarly, the extent of transportation, storage, protective services such as refrigeration result in lower farmer’s share. E. Misconception of the Marketing Margin i. Marketing Efficiency: Many people, especially farmers and consumers believe that a small margin denotes marketing efficiency and this is more desirable than large margin. If this were true, then, direct sales from farmers to consumers or roadside sales by farmers where the market margin is zero, will denote high marketing efficiency. But the fact is, efficiency cannot be judged solely by the size of the marketing margin. ii. Elimination of Middlemen: There is also the belief that there are ‘too many’ middlemen in the marketing chain causing high margins, and that margins can be reduced by eliminating middlemen. The fact is, middlemen can be eliminated but not their marketing functions which are the direct cause of high margins. iii. Large Margins Cause Low Farm Prices: There is also the misconception that large marketing margins causes lower farm prices. The fact is , marketing functions add both value and cost to the farm products. Thus an increase in marketing margins can increase retail value and prices of food as a result of cost of marketing functions. But of course, some ads, and promotions obviously increase retail prices which may not be necessary. iv. Are Margins Profits?: There is also the belief that marketing margins are profits to marketing firms, and these profits can be captured by farmers and consumers. As a result, both farmers and consumers cooperatives have been established in anticipation of reducing margins and profits. But the fact is, marketing margins consist of both cost and profits, and there is no guarantee that farmers or consumer cooperatives will perform without cost or perform marketing functions as efficiently as marketing firms. D. Incidence of Margin Changes. Incidence of changes in marketing margin is divided into two main parts: 1. Incidence of changes due to the introduction of new services 2. Incidence of changes related to existing services. 1. Incidence Of Changes Due To The Introduction Of New Services: With the introduction of new services and other things remaining the same, the margin is likely to be larger, and this changes is usually reflected DS primarily as a higher retail price. However, the PS consumer has a choice of buying the older PR2 product at the old price or the product with PR1 new services at the new higher price. If they M1 M2 accept the new product, then the incidence of PF this change in the marketing margin is on the PD2 PD1 consumer, and this appears as a new primary DD demand (PD2) at a higher price level (PR2). The price rises from PR1 to PR2 because producers shift the cost of the services to the consumer, and this results in an increase in the derived demand. 2. Incidence of Changes Related to Existing Services: If the cost of providing an existing set of services changes, the effect is generally to change both retail and farm level or producer prices. Producers will bear DS2 part of this cost and consumers bear DS1 PS the rest. There will be an increase in the margin, and this will appear as a PR2 decrease in the derived demand PR1 (shifting it downwards from DD1 to DD2) and an decrease in the derived M1 M2 P F1 supply (shifting it upwards from DS1 PF2 to DS2) relations for the product as DD2 PD shown in the figure. The consequence DD1 will be an increase in the retail price from PR1 to PR2 and a decrease in the the Q2 Q1 farm price from PF1 to PF2. A decrease in the marketing margin will have the opposite effect. We must also understand that we have assumed a competitive market structure in these discussions so that margin changes are reflected through the marketing system. The incidence of the magnitude of the price changes on consumers and producers as a result of changes in the marketing margin will depend on the elasticities of the demand and supply functions. If the demand function is more price inelastic than the supply function, then the magnitude of the price change at the consumer level will be greater than at the producer level as shown in the figure above. If on the other hand the supply function is more price inelastic than the demand function, then the magnitude of the price change at the producer level will be greater than at the consumer level as shown in the figure above. For many agricultural products, the supply function is thought to be more price inelastic than the demand function. In these cases, the incidence of a given margin would be greater at the farm level than at the retail level. E. Market Structure, Margins and Prices We have assumed a competitive market structure in these discussions so that margin changes are reflected through the marketing system - i.e. a change in the marketing margin affects prices at both the retail and the farm levels. For example a reduction in the transportation cost for moving a farm product to a processing center will initially accrue as benefit to the middlemen. But with the assumption of perfectly competitive market structure, the lower transportation rate will be passed on to the farmers as higher price and to consumers as lower prices, or a combination of the two effects. The higher profit benefits accruing to the middlemen as a result of lower transportation rates will attract more firms to enter the industry. As these new firms compete for products at the farm level, the result will be higher farm prices, and as they compete to sell more to consumers, the result will be lower retail prices. Thus the lower transportation costs affects both farm and consumer prices (depending of course on the elasticities of demand and supply). In real world however, the structure of the food marketing system does not fulfill all the conditions of a perfectly competitive model. With some monopolistic power, agricultural marketing firms retain all or part of the benefits of cost decreases as added profits while passing on higher cost to consumers and producers. Methodical Analysis to Market Margins There are many methods for analyzing marketing margins. The criteria for selecting a method is influenced by factors such as: 1. The availability of statistical data and financial support to carry out the study. 2. The characteristics of the market products to be analyzed e.g. perishability, seasonality 3. Nature of the marketing channels- traditional/new distribution system, # of middlemen 4. The objective of the analysis- type of margin to study (absolute, relative, net etc) I. Descriptive Methods or Models There are Macro- and Microeconomic methodologies in describing marketing margins. a. The Macroeconomic Approach: Aims to identify the role of marketing margins in the general economy. There are 2 ways of doing this: 1. National Accounting or GNP Approach: Sectors of the economy - e.g. gov't, households, businesses etc. are studied to verify marketing margins. But because the great aggregation used in this system, the usefulness of this method is low for evaluating MM. 2. Input-Output (I-O) Approach. This have the advantage of focusing the attention on different economic units. The output (pdn) system is detailed enough to account for services, final consumption, export and investment. Its major disadvantage are: - there is considerable aggregation due to the diversity of products and enterprises, production. - cost increase along marketing channel preventing usage of uniform cost b. The Microeconomic Approach: This gives information about the various components of the costs, structure and financial situation of firms involved in the marketing process. There are two main methods of microeconomic analysis. 1. The Functional Method: Analyzes the different economic activities or function associated with each level of the system - e.g. farming, wholesaling, retailing etc. To use this method, some countries have sampled some enterprises that provide regular data on economic activities such as products, number of employees, costs, subsidies, taxes, benefits etc. 2. The Vertical or Product Focused Method: This method follows the product through the marketing process, noting prices, quantities, cost, etc. on each transaction. The problem arises when there is a significant transformation, and it is necessary to determine the conversion factors (between raw and transformed products) and when there are by-products. II. Algebraic Analysis Here marketing margin is shown as a combination of constant and variable factors. There are 3 hypothesis in this analysis: 1.Margin as function of retail price: M = a + bPR, where M = AMM, PR retail price 2. Margin as function of quantity marketed: M = c + dQ, 3. the margin as a constant percentage, either of farm or retail price: M = kP Retailers usually use hypothesis 1 to calculate marketing margins. Wholesalers usually use constant percentages or hypothesis 3.