Third Sector Partnership Council

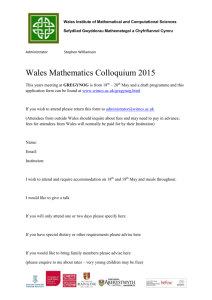

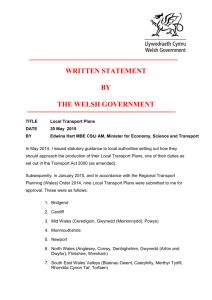

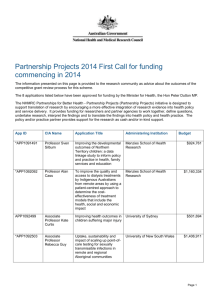

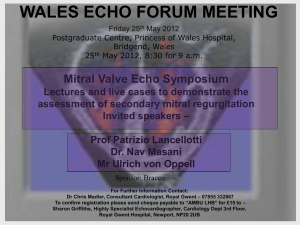

advertisement