41. Politics in the Gilded Age

advertisement

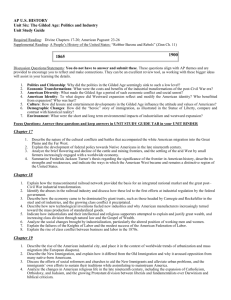

Politics in the Gilded Age Please note that despite that fact that the Gilded Age is the time when the labor movement began to pick up in the US, we are not talking about guilds. This word gild means to cover a substance of lesser value in gold plate. Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) and a lesser-known writer, Charles Dudley Warner, wrote a novel about this era and called it, The Gilded Age. The name stuck, and historians have used it ever since to convey the essence of a time when boom-and-bust businessmen were aided by corrupt politicians from 1865 to 1900. The idol of American greed looked lovely on the outside, but inside was cheap and dirty. At least that is the common assessment. The atmosphere of politics in the Gilded Age was equally tarnished. Both major political parties were rife with favoritism, fraud, and bribery. By 1870, newspapers strove to expose scandals, and both they and political cartoonist Thomas Nast could not have found a better target than William Marcy Tweed, otherwise known as “Boss” Tweed. Tweed was the head of Tammany Hall, the headquarters of the Democratic Party in New York City. While not holding elected office himself, Tweed controlled New York’s politics and looted taxpayers of anywhere from $75-$200 million. Clever tactics emanated from the Tweed Ring to fake bills, award false contracts, pay fictitious fees and otherwise perform the Gilded Age political dance—putting public money in private pockets with both hands. While in charge of constructing a new courthouse for New York City, Tweed siphoned off $11 million that supposedly went to the plasterer. The Tweed Ring bought so many “chairs” for the courthouse at $5 each that if they were set in a long row it would stretch seventeen miles! Thomas Nast fiercely exposed Boss Tweed’s image to public ridicule and was even instrumental in Tweed’s downfall, as we shall see. The first transcontinental railroad provided the context for another huge debacle. The Union Pacific Railroad hired a construction company called the Credit Mobilier to build their portion of the transcontinental line. The UP apologized profusely to the US government as they asked for more money for paying the continually rising construction costs those dastardly folks at Credit Mobilier were charging, but—lo and behold—the leaders of the Union Pacific were also the leaders of the Credit Mobilier who were awarding themselves huge profits! When an investigation ensued, the canny businessmen hushed up the findings by allowing Schuyler Colfax, Grant’s vice president, to “purchase” stock. When the whole scandal came out, Grant got rid of Colfax for his second election, but nearly every other federal agency under the Grant Administration produced scandals. The Republican Party lost the moral high ground we discussed under Reconstruction which partly contributed to the dawning of the era of “Jim Crow.” We have already said that Ulysses S. Grant was an honorable man who was not a good judge of character. His presidency is the first deeply corrupt presidency even though he himself was not involved. His chosen men in the Treasury Department allowed customs officials to charge extra tax on imports, which was pocketed. The Navy Department showed favoritism in awarding contracts while unscrupulous administrators pocketed kickbacks. The War Department accepted bribes from Indian traders and looked the other way as the Indian Bureau thieving went on apace. The closest scandal to touch Grant in the White House was known as the Whiskey Ring. The Internal Revenue Service tried to collect increasingly high excise taxes, but IRS agents kept raiding distillery warehouses that turned up empty. It was discovered that President Grant’s private secretary, Orville E. Babcock, had been tipping off the whiskey men to warn them of the “surprise” inspections. The Whiskey Ring bribed Babcock with money, diamond jewelry, and prostitutes! As the scandal emerged and before Grant knew who was at the bottom of it, he said, “Let no guilty man escape!” When Babcock was caught and put on trial, the President of the United States appeared and testified of Babcock’s “integrity and efficiency.” Orville Babcock was not only acquitted but remained on staff! Can you imagine such a thing happening today? People are fired from the staffs of even presidential candidates for what they say, let alone for committing crimes. In the wake of these and other scandals, another great American reform movement was born. This one was called civil service reform. Men like Babcock and those in the various corrupt departments were known as civil servants, ironically. The Civil Service Reform movement wanted to make civil servants, or those employed by the government, to have to pass examinations proving they were competent for their position rather than just the beneficiary of patronage in the spoils system. William Curtis, the editor of the magazine Harper’s Weekly, was the chief proponent of civil service reform and pushed Grant and the Congress to create the Civil Service Reform Commission in 1871. Grant shrewdly named Curtis to head the Commission in order to quiet him. When Grant won his second term in office, he promptly ignored Curtis and the Commission his own Administration had initiated. Curtis resigned in protest. Rutherford B. Hayes, winner of the contested Election of 1876, had campaigned on a platform of civil service reform. To win the Republican nomination, Hayes had to beat back New York Senator Roscoe Conkling who was an immensely popular and canny spoils system devotee who headed up patronage for the Republicans in the Congress. Republicans who opposed civil service reform were called Conklingites or Stalwarts. James A. Garfield, the winner of the Election of 1880, forced the resignation of Conkling from the Senate even though he was a Republican president. Garfield is one of the most decent men to ever be president, and he could translate into Latin and Greek simultaneously by writing with both hands on a chalkboard, but he got shot. Charles Guiteau, a frustrated office-seeker, shot Garfield and said, “I am a Stalwart, and now Arthur is President!” The president lingered for two months growing steadily sicker from an infection because the doctors could not find the bullet. In desperation, they brought in Alexander Graham Bell who had invented a metal detector, but they forgot to remove the president from his mattress that was filled with metal springs. Garfield died, and Chester Arthur, an old Stalwart who had been his vice president due to a compromise, was indeed president. Congress called for examinations for many federal jobs with the Pendleton Act in 1883. Critics said this reform merely created a professional bureaucracy, the very thing Andrew Jackson had opposed with his reform called rotation in office. Washington, especially, was not “cleaned out” by the Pendleton Act. Maybe the Gilded Age idol had mud inside like the muddy streets of our nation’s capital which was still without paving. Speaking of filth, did you know New York City released pigs into its streets until 1900 to have them eat up the garbage? The Gilded Age was dirty in more ways than one. As far as the national parties were concerned, they both had corrupt goals. Republicans were almost entirely unchallenged in the presidency through this era and their absolute control bred corruption. They claimed to be trying to include the Northeastern urban worker and the Midwestern farmers in their plans, but little was done to back that up. Democrats focused on repairing the Solid South and re-establishing party bosses in big Northern cities to follow the pattern set by Boss Tweed. In fact, both parties began to sound much the same in their rhetoric. Their world views were similar; their social structure was similar. Both parties were funded and led by wealthy professionals while maintaining a front of equality of all men. Both parties played upon prejudices and preferences of the people using images and giving impressions. One distinction of note, however, was that the Republican Party couched itself as a party of reformers (the Whig legacy) who piously imposed standards. Largely led by business leaders, the Republican Party was convinced there was one best way to live, and it was Protestant. Nativism, therefore, camped with the Republicans through the Gilded Age. Democrats, on the other hand, were a much more ceremonial party that valued appearances rather than personal purity. Preaching tolerance, they found room for Catholics as well as Protestants, embraced immigrants, and were much more laissez-faire on morals. Throughout the Gilded Age the legacy of the Civil War inspired high interest in national politics and elections. The six presidential elections averaged an incredible 78.55% voter turnout. Even in off-year congressional elections their 62.8% average turnout dwarfs our modern voter turnouts even for presidential elections. The “bloody shirt” rhetoric of the Republican Party ramped up the tension as they blamed the South and the Democrats for the Civil War. The South kept the Lost Cause alive to unify the Democrats, and through all these elections 30 states were stable politically. Sixteen always voted Republican, and fourteen always voted with the Democrats. Five variable states therefore made all the difference. These states were Connecticut, New York, Indiana, Nevada, and California. Grover Cleveland had been the reform governor of New York and was the only Democrat to win the presidency in the Gilded Age. He is also the only president to win non-consecutive terms (in 1884 and in 1892), another sign of hard contests. Seven of the ten congressional elections put Democrats in the House of Representatives to balance the Republican presidents. During the 1880s, three presidents won by only 1% of the vote in the key five states. Garfield and Cleveland won theirs by fewer than 25,000 votes! Behind the nearly Civil-War-re-enactment election campaigns hovered the specter of widespread corruption. George Washington Plunkitt openly acknowledged that he and his friends at Tammany Hall in New York City were growing wealthy as “public servants.” Plunkitt particularly liked to follow fire engines with blankets and hot chocolate in hand to distribute to displaced fire victims. He would get them new housing and a job if they needed one and, of course, ask them to vote for the Democratic Party. Power was for giving away to friends in the form of patronage, and Plunkitt openly discussed “good graft vs. bad graft,” when the nation was beginning to understand that all graft was bad. Party bosses sat like giant spiders at the center of webs of influence—allpowerful, unsleeping, devious, and ruthless. Bosses commanded by the strength of their will, through cleverness, audacity, and luck and were the closest manifestation of Machiavelli’s Prince America has ever seen. A favorite ploy was to buy round after round of drinks for the house and for all his friends and would-be friends (with money from the Party machine) while never drinking himself. He was on duty. He was listening and watching for leverage whereby he could later blackmail people he needed to manipulate. When his party held power, a Boss could give out jobs, appointments, contracts, licenses, permits, pardons, and outright gifts to his faithful supporters. Boss Tweed built the aforementioned New York City courthouse, completed plans for Central Park, and began the city’s transit system all the while saying bribery, patronage, and corruption were necessary. And Central Park is nice, isn’t it? The main role of presidents beginning with Hayes was simply to stand by the traditional image of America preferred by his party and to dole out jobs. Some were hardened to patronage like Chester A. Arthur who still passed out jobs while signing the Pendleton Act over the dead body of James Garfield who had been killed by a Stalwart! Some Republicans began to either believe in civil service reform or to perceive it as the popular trend and to act like they believed it. Both types wound up being rejected by their own party and dispensed with in favor of some person not adverse to graft. As a whole the Gilded Age presidents were rather unimaginative and un-great. They all seem to blend into one bearded or bewhiskered man and are collectively known as the Forgotten Presidents. Most from Lincoln on wound up viewing the presidency as a nightmare and were continually plagued by office-seekers. Even Cleveland, the Democrat who had been a reform politician throughout his political career and who was elected to the presidency to end Republican corruption faced a line of office-seekers from his own party when he got to the Oval Office. Let’s look at one Gilded Age election closely. The Election of 1884 pitted James G. Blaine against Grover Cleveland. Both parties’ platforms were virtually the same, so how could either win? They both resorted to personal attacks on their opponent. The Republicans made much of the fact (which has now been drawn into question) that Cleveland had an illegitimate son back in Buffalo, NY. Blaine’s participation in corruption was exposed with the publication of the “Mulligan Letters.” These were letters uncovered by James Mulligan that were signed by Blaine, discussed graft, and finished with the cryptic line, “Burn this letter.” Never write that line on a letter if you are a politician (or type “Delete this email”). People kept the letters almost as if they were an invitation to black mail Blaine or sell him out to the Democrats, which they did. Blaine also made two other public mistakes. He was seen dining at Delmonico’s, one of the finest restaurants in New York City, with none other than the likes of Carnegie and Rockefeller which seemed to prove that these Robber Barons had the government in their pockets. Blaine also blundered when he failed to say anything against a speech from an irate Protestant clergyman who spoke just before him at a rally. Blaine, apparently, was concentrating so hard on what he was about to say that he didn’t even hear the preacher shout that the Democratic Party was the party of “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion!” When he didn’t temper that slogan, Blaine gave the appearance that he agreed and offended the Irish, Roman Catholics, and Southerners all at once. Workingclass voters were swayed to vote for the Democrat, and Cleveland won New York, one of the crucial five states, by only 1,200 votes among over one million! Keep in mind that it’s rather incredible that Cleveland could only amass such a small margin of victory in his home state where he was governor! Benjamin Harrison, President William Henry Harrison’s grandson, won from Cleveland for the Republicans in 1888 and dumped Cleveland’s 30,000 postmasters and replaced them with Republicans with, one commentator said, “. . .all the warmth of a dripping cave.” Keep in mind, however, that the Reform President had put those 30,000 postmasters in office from his own party in just four short years. By 1900 civil service reform amazingly pressed forward with 100,000 federal jobs with rules enforced for hiring, but success would take a much more forceful personality in the White House than any Gilded Age politician of either party, and that individual is coming, don’t worry. One might say the United States got the government it deserved in the Gilded Age, an era of what became known as the Custodial Presidency. Congress dominated the making of federal policy until one of the most powerful presidents ever arrived on the scene. Congress was confronted with an interesting problem—how to spend a federal surplus every year from 1866-1893. During the 1880s this surplus even averaged $100 million a year! How do you suppose they handled it? Would they have given money back to the states or lowered taxes? No, they created entirely new federal jobs for their buddies who put that money into their pockets without the actual inconvenience of having to steal it. Justice was done, occasionally, though. Boss Tweed fled the country when the outrage at his graft got too hot. Interestingly, he was caught in Spain because he stood at a billboard with a Thomas Nast cartoon from a newspaper stuck on it, musing over Nast’s animosity, I suppose. A Spanish policeman strolled by and saw the likeness of Tweed holding two children in the cartoon which Nast had used to symbolize some people in New York that Tweed’s machine were pushing around. The policemen recognized the likeness of Nast’s caricature in the man standing next to him and assumed the cartoon was a wanted poster for a kidnapper. William Marcy Tweed was arrested, extradited, and died in prison by 1878.