Chalk to Dust - WordPress.com

advertisement

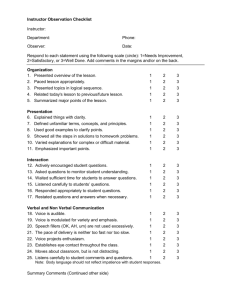

Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin Chalk to Dust--Mouse to Recycle Bin: Traditional Class Goes Non-traditional Mary Alice Moore English 808 Dr. Michael Williamson December 14. 2006 1 Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin Introduction Days of Dust “Who would like to erase the blackboard?” asked my second-grade teacher. “Me, Sister! I’ll do it!” I shouted raising my hand high in the air. “OK, Mary Alice, you can do it.” I smiled a smile of satisfaction making a mad dash for the front of the room, clutching the eraser tightly as though I were hugging it, and I started erasing that dreadful arithmetic assignment into oblivion that Sister had printed on the board earlier in the day. Dust to ashes, ashes to dust. I remember that chalk dust smelling so good. I loved erasing the blackboard so much that I regularly volunteered to stay after school to not only to erase the board but also to wash it. There was nothing better than returning home from school and hearing my mother say, “Honey, you got chalk dust all over your uniform again.” Little did I know then that thirty years later erasing a blackboard would take on another meaning. I discovered this new meaning in my masters program when my Teaching Writing class’s instructor proclaimed one night, “Next week we’re all going to the computer lab to learn how to use the blackboard.” Some of us looked at her wondering if maybe she had ingested too much toxic chalk dust—especially since there was a blackboard behind her. I looked around the room at my classmates. Some nodded in agreement with the teacher while others looked confused like me. Remembering what my grandmother used to say, “There’s no such thing as a stupid question, Dear. The only stupid question is the one you didn’t ask.” I raised my hand. “Yes, Mary Alice,” said the teacher. 2 Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin 3 I said, “Ah, what are you talking about?” I heard a few sighs of relief coming from the classmates who were glad I was the one who had asked the dumb question. Blackboard turned out to be a computer program that allows instructors to construct, deliver, and manage web-based components for courses. It can be used to include online elements to complement a traditional course, or an instructor can design a completely online course with few or no face-to-face meetings (Blackboard). Blackboard allows for many features using the computer to create them: Course announcements Asynchronous threaded discussion Synchronous group chat, with or without tools such as white board, group web browser, course browser, and more Online quizzes and surveys, with automated grading and statistics capacity Course assignment and documents areas Course-related external links Online file sharing Timed release of quizzes and other course materials Student rosters, e-mail, and online gradebook Group project areas (Blackboard) Our professor lectured us about the features of Blackboard and how the world is advancing technologically and how our futures as writing teachers will include using technology, and so we better learn how not to be afraid of it. In other words: Get used to it. Therefore, the following week, we went off to the computer lab. A nice computer nerd gave us individual help setting up our Blackboard accounts. We obtained secret passwords to log in to the Blackboard Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin site, thus learning how to participate in an online class. We practiced and improved, but there were a few rough spots along the way. “Ah, Mr. Computer Guy, I need you! The Blackboard erased my assignment. Oh my God! Where did it all go? It’s gone,” I anxiously screeched—a blank white screen staring back at me. As Mr. Computer Guy leaned in closely (a little too closely) over my shoulder and clicked away on the computer’s mouse, he said accusingly, “What did you do?” I said, “All I did was click on the mouse.” “Yeah, but what did you click on?” was his answer. I said, “I don’t know.” “ Maybe you put it in the recycle bin,” he said. “I don’t think so,” I said. It wasn’t there. “Well, it’s gone. Start over,” was all Mr. Computer Guy had to say. I wished I had an eraser to throw at him. Days of Technology I ended up liking Blackboard, though. What started as my participating in a Blackboard assignment for school led to a part-time job that found me advising papers for students who attended a university that offers mostly online courses—University of Maryland University College (UMUC). And that position led to a full-time one coordinating UMUC’s Effective Writing Center (EWC), which is entirely an online writing center. When I started my current PhD program, I relinquished my full-time position and went back to part-time work for the EWC. I now coordinate the EWC Fridays through Sundays, and so it seems only natural that the next step in my online life should be teaching classes online. I anticipate this while working on my dissertation; the convenience of working from home will give me the much-needed 4 Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin freedom to work on my dissertation. There are many techniques teachers and students use interacting online—enough to fill up a dissertation. With that in mind, I am taking this opportunity to research only some of the ways that teachers and students can effectively interact in an online classroom environment. Traditional Interaction Versus Non-traditional In the traditional classroom, student interactions take place face-to-face (f2f) between the instructor and the other classmates. Much of the student interaction/socialization takes place before the start of class; that’s the time when students chat with each other about their assignments, their life outside of school, and discuss their feelings regarding their instructor. The students develop their relationships further walking to and from class together. Students develop a relationship with the instructor during class time by responding to the teacher’s questions and taking part in class discussions. Students also feel free to approach the instructor after class if they have an issue they would like the instructor to address privately, which might lead to them making an appointment for a f2f conference during the instructor’s office hours. These meetings might be held in the instructor’s private office, or if the instructor is one of those laid-back people, the meeting might be held in the campus coffee shop. These f2f meetings are when a relationship between teacher and student develop and strengthens. Students and instructors take comfort in reading each other’s body language and listening to the tones of each other’s voices. Takimoto-Makarczyk notes: “In the traditional setting, the instructor is physically present with all the learners and can receive immediate feedback through visual or verbal cues” (n.d.). The instructor is the one in control in the traditional setting Students think of the instructor as an “expert” in his or her field, and the instructor is 5 Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin used to being in that position. So, how does this all change in the online environment when there is no physicality present? Instructor Perspective The first thing that changes in the online environment involves the instructor. The teacher has to learn to relinquish control—the control that was second nature to him or her in the traditional setting. According to Palloff and Pratt, “Instructors need to be willing to give up control and allow learners to take charge of the learning process” (Palloff & Pratt, 2005). The word “willing” is pivotal in understanding this concept. Giving up control is hard; this does not come easily to a traditional teacher, but if an online class is to succeed, the instructor has to give up that control. The difference between traditional teaching and online teaching is that in the online class, the teacher’s role changes from that of teaching (control) to that of facilitating (guide). Online, the instructor guides the learning process while in the traditional classroom the instructor dictates the learning process. Online, the instructor becomes more of a coach than a teacher. Collins and Berge, who provide tips on facilitating, believe that as a facilitator or coach the instructor is responsible for keeping discussions on track, contributing special knowledge and insights, weaving together various discussion threads and course components, and maintaining group harmony (Collins & Berge, 2001). Many educators think that the kind of community that is formed through interactions in the traditional setting cannot be formed in the online environment. While the online environment is different, research has shown that it is not as different as those unconvinced educators believe. The same interaction that is necessary for a traditional classroom to function can take place in the online classroom as well; the exception being that the online student now has more responsibility in his or her own learning. According to Palloff and Pratt, “The 6 Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin instructor’s responsibility is to set the tone and begin the development of the learning community; the ball must then be thrown to the learners” (Palloff & Pratt, 2005). Some would say that the traditional teacher has the same responsibility, and they do have that responsibility to a certain extent; however, the online instructor needs to take his or her responsibility that was fostered in the traditional setting a few steps further. In simpler terms, instructors need to think outside of their traditional teaching comfort zones. Thinking of the online instructor’s role as akin to being a community leader and/or managing a neighborhood condominium association can help keep this new role in focus. The teaching role changes from one of individualism, one-on-one, f2f methodology/pedagogy to one of all-encompassing, managerial and putting the community as a whole first methodology/pedagogy. Below is a chart that clarifies these changes more clearly. Changing Instructor and Student Roles Changing Instructor Roles Changing Student Roles From oracle and lecturer to consultant, guide, and resource provider From passive receptacles for hand-me-down knowledge to constructors of their own knowledge Teachers become expert questioners, rather than providers of answers Students become complex problem-solvers rather than just memorizers of facts Teachers become designers of learning student experiences rather than just providers of content Teachers provide only the initial structure to student work, encouraging increasing selfdirection Teacher presents multiple perspectives on topics, emphasizing the salient points Students see topics from multiple perspectives From a solitary teacher to a member of a learning team (reduces isolation sometimes Students refine their own questions and search for their own answers Students work as group members on more collaborative/cooperative assignments ; group interaction significantly increased Increased multi-cultural awareness 7 Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin experienced by teachers) From teacher having total autonomy to activities that can be broadly assessed From total control of the teaching environment to sharing with the student as fellow learner Students work toward fluency with the same tools as professionals in their field More emphasis on students as autonomous, independent, self-motivated managers of their own time and learning process More emphasis on sensitivity to student Discussion of students’ own work in the learning styles classroom Teacher-learner power structures erode Emphasis on knowledge use rather than only observation of the teacher’s expert performance or just learning to "pass the test" Emphasis on acquiring learning strategies (both individually and collaboratively) Access to resources is significantly expanded Figure 1: This chart shows changing roles between instructor and student (Collins & Berge, 2001). The points made with this chart are interesting because, as the chart asserts, “Teachers become expert questioners, rather than providers of answers” (Collins & Berge, 2001). In the traditional classroom, the instructor is the one who normally answers the questions that the students posit. In the online classroom, this method of teaching is reversed: “The instructor contributes their special knowledge and insights and uses questions and probes for student responses that focus discussions on critical concepts, principles and skills” (2001). Another significant point from the chart above is the need for the teacher to become a team member in the online classroom community: “From a solitary teacher to a member of a learning team (reduces isolation sometimes experienced by teacher” (2001).It is easier to feel isolated in the online environment than it is in the traditional classroom. The way to alleviate this isolation is to create a sense of “presence” to the students. However, how can one be “present” in a virtual environment? According to Stone and Chapman from North Carolina State University, researchers Picciano and Wheeler have found that: 8 Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin Instructor presence in the online classroom requires careful planning and foresight, at the earliest stages of course development. The research on distance learning suggests that the students need more support and feedback from their instructor than would be required in a face-to-face course, since time and space separate them from the instructor and their classmates. ( qtd. in Stone & Chapman, 2006) With that said, when and how does an online instructor make his presence known? Common sense dictates that the instructor makes his or her presence known immediately. This can be done by using the many components that the online classroom program/software allows. These components can take the form of personal discussion folders, live chat, personalized email, audio/video, regular updates and feedback, group discussion and private places. (Woods & Ebersole, 2003). As previously stated, the instructor sets the tone for the classroom. The first step in setting this tone is for the instructor to create a private space in the classroom where the students can “talk” about themselves, a place where they can introduce themselves and get to know each other. Adjunct Professor Jerald Levine of UMUC does this by creating three topics in his WebTycho, which is similar to the Blackboard interface: My training for online teaching very effectively moved me in the direction of community building, particularly through use of three topics I continue to use in my “Getting Started” conference: Introduce Yourself, Name the Cyberbar, and Course Expectations. In my Introduce Yourself topic, I ask my students what they liked to be called—other than “Dude” or “Girlfriend” so as to avoid confusing one another … I ask them to share some biographical information with all of us, and to respond to three classmates’ bios. I respond to the students as well, addressing them by the names they prefer and finding some small but unique point of connection to each. (Levine, 2004) 9 Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin 10 It is important to take notice of how Levine sets the tone for his class. Levine sets up a friendly, welcoming atmosphere by using humor. Humor is a very important tool to use when communicating online. It relaxes the students and can create a much-needed camaraderie with each other. Unlike the traditional classroom, geographical distance can lead to a lack of solidarity among class members. Palloff and Pratt agree that seeing humor in text and laughing at ourselves online is another way for the online participants to bond with each other, But when using humor, they assert that one has to be careful: “The issue online is that humorous comments may be misinterpreted due to the absence of visual cues. Consequently care in the wording of a humorous comment, the use of emoticons … or bracketing the emotion involved, such as [just teasing here] can help recipients of the message understand the intent” (2005). Student Perspective The number one factor that concerns students in an online class is how well and how the instructor will make his or her presence known to the student. Will the instructor be readily available to answer their questions and “listen” to their concerns? How immediate will the instructor’s responses be? Immediacy on the part of the instructor responding to student inquiries is crucial for making the student feel acknowledged and validated. Since online class information is written in text form instead of verbally spoken as done in traditional settings instructor responses need to be sent (emailed/posted) swiftly and explained thoroughly. Debra D. Kuhl of the University of Arkansas credits Dewar with asserting that online instructors should maintain office hours each week, encouraging interaction and communication with students, and that instructors should incorporate the use of chat rooms that allow real-time conversation; these rooms allow for instantaneous feedback and, clarification of concepts (Kuhl, 2002). Also, most studies suggest that in order for the student to feel “heard” by the Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin 11 instructor, instructors should respond to all emails from students within 48 hours; although, Woods and Ebersole disagree slightly, “As a rule of thumb, we suggest responding within 24 hours” (2003). Online learning is not for everyone. It takes an independent, disciplined person who is able to motivate themselves to work alone. Palloff and Pratt state that there are five characteristics that an online learner should possess in order to successfully complete an online course: Openness: Willingness to be open about personal details, of his or her life, work, and other educational experiences. Sharing this information can be encouraged by the instructor early on through the posting of introductions and bios. Flexibility and Humor: Going with the flow of an online course, not being rattled when things go wrong, and even facing the minor crises with humor help to keep the sense of community moving. Honesty: The ability to be honest in an online course needs to be modeled first by the instructor, and then others will feel comfortable in following suit. When students become equally concerned about the development of a learning community and are willing to jump into the fray in a professional way, their honesty is seen as something in service of community development. Willingness to Take Responsibility for Community Formation: Honesty is closely related to this. Students should be willing to take responsibility for community formation. Willingness to Work Collaboratively: Collaboration is one of the key features of the learning community. Participation in an online course is not the same as Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin 12 collaboration. By asking students at the beginning of a course to share their learning goals for the course, the instructor creates an atmosphere where collaboration can flourish. (2005) Conclusion Before I conclude this paper, I think it is important to talk about an important aspect of online learning interaction that tends to get overlooked: technology. Both the instructor and the student need to be comfortable working with technology with the instructor more so than the student. The student will look to the instructor to know how to “fix’ technological problems that occur in the classroom. According to Collins and Berge: The instructor must first find themselves comfortable and proficient with the technology and then must ensure that participants are comfortable with the system and the software that the conference is using. The ultimate technical goal for the instructor is to make the technology transparent. (2001) I like that word, “transparent.” My Blackboard experience during my master’s program made technology appear more transparent. I was more comfortable with computers after my Blackboard experience. Before my encounter with a Blackboard online classroom, I never would have even attempted to be part of one. My initial fears and apprehensions were alleviated by others in the class who were more computer literate than I was at the time. I did not know it then, but Blackboard was preparing me for my current position working at the EWC. At the EWC, we use WebTycho classrooms. We have utilized all the components and tips that I have spelled out in this paper. We get to know each other in a private space that was set up for us to “hang out” in, and we have monthly synchronous chats so that we can “talk,” and we have a bulletin board where we can “pick up” our messages. Some of us have even Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin become friends, and every once in a while we leave the cyber world behind and slip back in to the real world. We pick up our landline or cell phones so that we can hear each other’s voices. And every once in while I find a greeting card made out of real paper in my snail mail mailbox from a virtual co-worker. It’s a nice feeling to find a card made of authentic paper in my real mailbox instead of an e-greeting in my email mailbox. And the feeling is made even sweeter when I see that the paper card traveled all the way from Michigan to Pennsylvania. I can’t remember if I ever had a “traditional’ co-worker ever actually mail me a card; they probably just handed it to me at the office. The online world has become much more “natural” to me during the last five years. If someone had told me back in second grade that the blackboards and the people that make up the traditional classrooms would be taking field trips to the virtual world toting their blackboards with them, I never would have believed them. I like this virtual world, and accept that it is here to stay. I admit that I need to learn more about technology, and look forward to doing just that. Nevertheless, I still miss cracking those erasers together and watching the chalk turn into transparent dust. And nothing can compare to hearing Sister say, “Job well done, Mary Alice.” 13 Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin 14 References Blackboard. Retrieved December 9, 2006, from http://www.edtech.neu.edu/blackboard/ Collins, M., & Berge, Z. (2001, October). Facilitating Interaction in Computer Mediated Online Courses. Retrieved December 9, 2006, from http://www.emoderators.com/moderators/flcc.html Kuhl, D. D. (2002). Investigating Online Learning Communities (Rep.). Arkansas: University of Arkansas. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED475750) Levine, J. E. (2004, May/June). Building a Sense of Community in the WebTycho Classroom. DE Oracle @ UMUC. Retrieved December 10, 2006, from http://polaris.umuc.edu/de/ezine/features/may_june_2004/community.htm Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2005). The Role and Responsibility of the Learner in the Online Classroom. 19th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching and Learning. Retrieved December 8, 2006, from http://www.uwex.edu/disted/conference/Resource_library/proceedings/03_24.pdf Stone, S. J., & Chapman, D. D. (2006). Instructor Presence in the Online Classroom (Rep.). Columbus, Ohio: Online Submission, Paper presented at the Academy of Human Resource Development International Conference. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED492845) Takimoto-Makarczyk, K. (Ed.). Encyclopedia of Eductional Technology: Online Interaction. Retrieved December 9, 2006, from http://coe.sdsu.edu/eet/Articles/interact/index.htm Woods, R., & Ebersole, S. (2003). Becoming a "Communal Architect" in the Online Classroom Integrating Cognitive and Affective Learning for Maximum Effect in Web-Based Chalk to Dust-Mouse to Recycle Bin 15 Learning. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, VI. Retrieved December 10, 2006, from http://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/spring61/woods61.htm