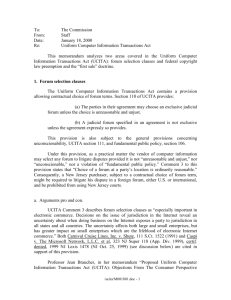

- New Jersey Law Revision Commission

advertisement