Hist - University of Puget Sound

advertisement

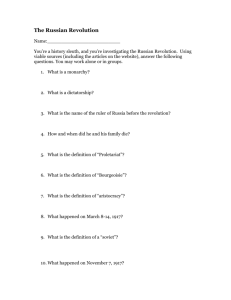

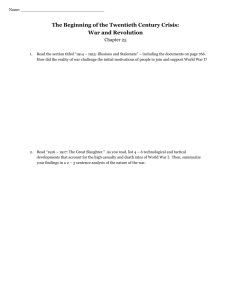

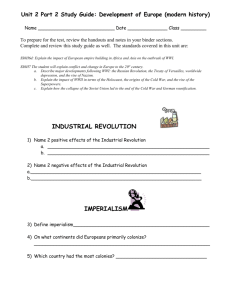

Hist. 124: The Russian Revolution Spring 2011 Seminar in Scholarly and Creative Inquiry Wednesday and Friday, 2-3:20, Jones 211 Benjamin Tromly Department of History Office: Wyatt 128 Email (preferred method of contact): btromly@pugetsound.edu Telephone: X 3391 Office Hours: MWF 12-1 or by appointment Class web resources: Course Moodle page: access through moodle.pugetsound.edu Course library page (with links to sources and other information): accessible through the library website subject guide at http://alacarte.pugetsound.edu/subject-guide/91-History-Subject-Guide The Russian Revolution was a defining event of the twentieth century. It transformed or shortened the lives of millions of inhabitants of the Russian Empire and, after a bloody civil war, produced the world’s first socialist state that polarized politics the world over. Interpreting “revolution” in a broad sense, this course examines political, social, economic and cultural revolutions in the Russian Empire between the end of the nineteenth century and the consolidation of the Soviet order in the 1920s. A wide range of readings—including historical studies, revolutionary programs, memoirs, diaries, and fictional works— illustrates how the revolutionary period was experienced and lived by people from different social and ethnic groups. Close reading, structured class discussion and scholarly papers will advance students’ skills in framing and exploring questions, establishing claims and evidence and responding to multiple and often controversial points of view. The course begins with an examination of the Russian old regime and its interlocked crises: economic underdevelopment, boiling social tensions, radical revolutionary movements, and destabilizing national divisions. We discuss different possible trajectories of change from 1905 to 1914, a period that saw the near-collapse of the autocracy and a short period of semi-constitutional rule, reform and intellectual exploration. The First World War reignited political, social and national upheavals that would only be put down by the Bolsheviks in the 1920s. Key questions will include: Was revolution inevitable in Russia and why? Could revolution have brought about political and social freedom rather 1 than the despotic Bolshevik regime? Finally, how did Stalinism emerge from the Russian Revolution? COURSE OBJECTIVES: • • • • To advance skills in critically evaluating arguments, developing academic writing and public speaking. To explore key questions of interpretation about the Russian Revolution. To provide an introduction to the historian’s craft of constructing of interpretations using evidence. To investigate the use of different kinds of sources and voices in understanding the past. COURSE TEXTS: The following titles are available for purchase at the Campus Bookstore and through online services. They are also available on two-hour in-library reserve at Collins Memorial Library. -Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution (NY: Vintage Books, 1996) Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001) -Mikhail Bulgakov, Heart of a Dog (New York: Classic House Books, 2009) -Course reader (listed as “CR” below). COURSE REQUIREMENTS: A. Participation (10%) This is a discussion class. You are expected to come to class having done the readings for that day and be prepared to offer questions and thoughts about them. Full participation in class discussions—not merely being present—is necessary for a satisfactory grade in the course. Note that active participation can take different forms, such as drawing connections, posing questions, and listening and responding to the comments of other students. B. Discussion papers (20%) (See instructions below) Each student will write 3 discussion papers. These papers give you an opportunity to consider an aspect of the readings for the day the paper is due and pose a question or raise an issue that the class as a whole might discuss. The due dates for these papers depend on which group you are assigned to (see below). 2 C. Take-home midterm exam (20%) Guidelines to be distributed in class. D. Final Project (35% overall) (See appendix to syllabus on final paper) The final project includes the following components: a. Prospectus for your final project (see instructions below) (5% of final grade) b. A 7-9 page analytic essay on a particular individual of your choice who lived and participated in the revolutionary period in Russia. It must include a bibliography (see instructions below) (25% of final grade) c. A short in-class presentation on your final project in the last few classes of the course. Presentations will be done in groups on related topics. (guidelines to be distributed in class) (5% of final grade) E: Quizzes (15% total) 4 quizzes will be given on dates indicated in the schedule below. The quizzes include multiple choice and short answer questions. They are designed to encourage reading and note taking. They do not require preparation beyond what is already expected of you: diligent reading, reflection on readings, and active participation in class. You may use your own notes on the readings during the exam but NOT the readings themselves, even if you have taken notes in the margins. You may not use a classmate’s notes during a quiz. Quizzes will not be offered multiple times, but if you have a valid reason for missing class that day your grade will not suffer from it. GUIDELINES FOR DISCUSSION PAPERS: You will belong to a paper group—A, B, C, and D. Discussion papers for your group are due on the days indicated in the course schedule below. Discussion papers are due in class. Given that the papers are meant to spur discussion, you will not receive credit for late papers (in certain circumstances, I may allow you to switch the day for which you write a discussion paper, but you should ask permission in advance). Discussion papers should be typed and be at least 3 full pages (12-pt. font, double-spaced). As in all writing in history, your paper should be analytical; it should make an argument. A major goal of the papers is for you to develop your own view of the material based on the reading. To this end, you must cite at least one primary source reading for the day. Of course, you will 3 want to cite ideas in the scholarly works we use (mostly the Pipes and Fitzpatrick volumes). But you should read these textbooks critically—do not simply borrow these books’ interpretations, but use the books to formulate your own views. You MAY wish to use your discussion papers grapple with questions I have provided under PREP for each class, but this is not necessary or recommended: the questions are listed under each class simply to give you a sense of some questions to ponder. Structure of discussion papers: The discussion paper has two components: a topic discussion and an issue identification. Topic Discussion: For the topic discussion, you should write 2-3 paragraphs about some aspect of the reading for that day that grabs your attention and you would like to discuss. The goal is not to summarize the reading. Instead, I would like you to identify some theme or issue presented in the reading and to interpret its significance. You do not need to deal with the reading as a whole; you may want to focus on a smaller part or passage. You may wish to draw comparisons between the readings of the day, or between the reading of the day and previous readings. You may wish to discuss how the reading relates to some larger issue in the class. You should include at least one quotation from the reading in your paper and at least two citations with page numbers (see bit on citations below). Issue Identification: The second component of the discussion paper is the identification of an issue that might be suitable for class discussion. This might consist of a brief question, or a few sentences of provocative thought, or simply the identification of a quote along with a brief statement about why you think it merits discussion. It may or may not be connected to your topic discussion. Be prepared to present your issue ID to the class. IMPORTANT DATES: Friday, Feb 4: Quiz 1 in class Wed.., Feb 23: Quiz 2 in class Friday, March 11: Take-home exam due at 5 PM in folder outside my office Fri, April 1: Quiz 3 in class Friday, April 8 : Library session in Collins Memorial Library 118 Monday, April 18: Prospectus for final project due at 5 PM in folder outside my office Friday, April 22: Quiz 4 in class May 13: final paper due at 12 noon in folder outside my office 4 COURSE INFORMATION: • • • • • • • • • Attendance at all class meetings is expected. Each unexplained absence is viewed with irritation and dismay; after three absences, the final grade in the course will be dropped by half a letter grade. I will distribute an attendance sheet at each class. You are responsible for making sure your name is on it. If medical or family emergencies prevent you from coming to class, please let me know before or soon after the class. I strongly encourage you to visit me in office hours. There is no need to schedule an appointment during scheduled office hours. If you are unavailable during these times, please contact me in advance by email to schedule a meeting. The best way to reach outside of class is via email. Please check your UPS email account—or an alternative account you provide to me—regularly. On occasion, I will send emails to the class to provide you with reading questions and important contextual information. I try to respond to email as quickly as possible, but I cannot promise that I will respond promptly to messages sent on weekends or holidays. Claims for academic accommodation for an individual’s learning disabilities must be directed at the beginning of the semester to Ivey West, Associate Director/Disabilities Services at the Center for Writing, Learning, and Teaching at 253.879.2692. All assignments must be submitted at the start of class on the due date or as otherwise instructed. Papers should be typed, double-spaced, and proofread, with page numbers and proper citations. Please submit papers in hard copy only. Late papers can be sent by email (be sure that you have attached the file). Late work will be penalized at the rate of ½ a letter grade per day late (a ‘B’ paper handed in two days late becomes a ‘B-‘) and will not be accepted more than five calendar days following the due date. Please notify me before the paper is due if health or family emergencies prevent you from submitting work on time. You are strongly encouraged to review UPS’s policies on academic honesty and plagiarism as detailed in the Academic Handbook. You are responsible for being familiar with the university’s policies. Plagiarism will result in a 0 on the assignment in question, with greater penalties possible. Students who want to withdraw from the course should read the rules governing withdrawal grades, which can be found at http://www.pugetsound.edu/student-life/student-resources/studenthandbook/academic-handbook/grade-information-andpolicy/#withdrawal 5 GUIDELINES FOR WRITTEN ASSIGNMENTS • • All written work should be double-spaced, 12 point font, preferably Times New Roman or something like it. Please put your name on the first page only (this allows me to grade “blindly”) On citations for written works: For all written works in the course, please use footnotes according to the Chicago Notes and Bibliography System (detailed in the library page for the course). You may cite course readings in an abbreviated way, for example: Pobedonostsev, History 124 course reader, 3 (course reader page number); all literature cited from outside the course readings should receive full footnotes. A bibliography is required for the final paper (not annotated), but not for the response papers or the midterm. COURSE SCHEDULE: Wed., Jan 19: Introduction to the course Part One: The Demise of the Old Regime Friday, Jan 21: Russia's old order The syllabus (please come with questions if anything is unclear) Walter G. Moss, “Lands and peoples: from ancient times to the present,” in A History of Russia (CR) Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 10-20 (“Official Russia”) “Pobedonostsev’s Criticism of Modern Society,” in Basil Dmytryshyn, ed., Imperial Russia: A Source Book, 1700-1917, 2nd ed. (CR) PREP: The goal of today’s class is to get a preliminary look at the autocracy that ruled Russia. What was wrong with the Russian autocracy at the turn of the century? Was Nicholas II’s ineffectiveness as a ruler a product of personal failures or the political traditions he represented? Pobedonostsev was an advisor at court and the head of the Russian Orthodox Church for many years. On what basis does he reject liberal and democratic politics? Why was autocracy appropriate for Russia? Why couldn’t the ignorance of the masses be remedied in his opinion? Wednesday, Jan 26: The Social Crisis of the Old Regime (group A) Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 3-10 (“The Peasantry”) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 10-18 Anton Chekhov, “Peasants” and “Gooseberries” (CR) 6 PREP: What was the status of the peasantry after the abolition of serfdom in 1861? Why were free peasants still, in many cases, discontent with the legal and political order? What values dominated peasant culture in Chekhov’s depiction? Is this fictional account consistent with the Pipes reading? Finally, how does Chekhov depict the nobility in Gooseberries? Why are the characters so tortured? Friday, Jan 28: Intellectual rebels in Russia (group B) Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 21-30 (“The Intelligentsia”) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 24-25 Praskovaia Ivanovskaia in Five Sisters: Women against the Tsar, 98-142 (CR) PREP: How does Pipes explain why so many educated Russians define themselves in fundamental opposition to the Tsarist system? Does Pipes pass a judgment on them, and do you find his account persuasive? What might Pipes have to say about Ivanovskaia’s memoir? Does it confirm his point of view? Wednesday, Feb 2: Lenin and Leninism (group C) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 26-32 Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 101-113 (“Lenin and the origins of Bolshevism”) K. Marx and F. Engels, excerpts from The Communist Manifesto (CR) “Lenin’s Conception of the Vanguard Party,” from Imperial Russia: A Source Book (CR) PREP: What was the appeal of Marxism, an ideology for industrial workers, in overwhelmingly peasant and agrarian Russia? The big question: did Leninism contradict classical Marxism or adapt it faithfully to Russian conditions? How did Lenin differ from other early Russian Marxists? What does Pipes have to say about the origins of Lenin and how his background might have been tied to his politics? Friday, Feb 4: Nationalism and anti-Semitism (group D) Edward Thaden, “Russification, “in Cracraft, ed., Major Problems in the History of Imperial Russia, 403-409 (CR) Chaim Zhitlovsky, “The Jewish Factor in my Socialism,” and Pavel Alexrod, “Socialist Jews confront the Pogroms,” in Lucy S Dawidowicz, ed. The golden tradition; Jewish life and thought in Eastern Europe, 411-422 and 405-410 (CR) Quiz 1 in class 7 Wednesday, Feb 9: 1905 and the collapse of the autocracy (group E) Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 31-45 (“The Revolution of 1905”) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 32-35 A Radical Worker in Tsarist Russia: The Autobiography of Semen Ivanovich Kanatchikov Reginald E. Zelnik, trans. and ed., 302-317 (CR) PREP: Kanatchikov was an industrial worker of peasant stock who became a dedicated Bolshevik. His memoirs were written after October. How does his memoir explain the rise of worker opposition before 1905? Why did the revolution of 1905 occur and how did the Tsar manage to survive the ordeal? How did Kanatchikov and his comrades view the intelligentsia? Friday, Feb 11: The Constitutional Experiment (group A) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 36-39 Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 45-56 (“Stolypin”) Petr Struve, “The Intelligentsia and Revolution,” in Vekhi / Landmarks: a Collection of Articles about the Russian intelligentsia, 145-154 (CR) “Rasputin, the Holy Devil” (CR) PREP: Today’s class focuses on the experiment with constitutional rule in the wake of 1905. Why was the figure of Stolypin so important for this period? To what extent does Pipes view Stolypin with sympathy? Struve, one of the founders of Russian Marxism, moved away from intelligentsia radicalism after 1900. The Landmarks volume brought about acrimonious disputes among educated Russians. Why was that the case? According to Struve, how should political oppositionists approach the reactionary Russian autocracy? Part Two: Imperial Decline and Collapse, 1914-1917 Wednesday, Feb 16: The brewing catastrophe: Russia in the Great War (group B) Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 56-75 (“Russia at War”) Kowalski, The Russian Revolution, 1917-1921, 20-31 (CR) PREP: How did WWI influence the longstanding tensions in Russian society such as the peasant problem, the intelligentsia problem, and the nationalities problem? What impact did Russia’s early losses in the war—the so-called Great Retreat of 1915—have on the country? Friday, Feb 18: The February Revolution (group C) 8 Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 75-97 (“The February Revolution”) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 40-49 Documents from Kowalski, The Russian Revolution, 1917-1921, 35-41 (CR) “Provisional Committee of the State Duma, Proclamation” (CR) PREP: Why did the unrest in Petrograd in February 1917 bring about the fall of the dynasty whereas the regime had survived decades of similar unrest and revolts? Of what significance were the actions of elites—particularly military leaders and politicians from the prorogued Duma—in bringing about revolution? Wednesday, Feb 23: Experiencing the February Revolution no reading quiz 2 in class Friday, Feb 25: The Revolution deepens: summer 1917 (group D) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 49-61 Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 113-128 (“The Bolsheviks’ Failed Bids for Power”) Kowalski, The Russian Revolution, 1917-1921, 51-57 (CR) Petr Petrovich Shidlovsky, “Things fall apart,” in The Other Russia, 54-63 (CR) PREP: On what basis did the Provisional Government claim the right to rule? What was the relationship between the PG and the Petrograd Soviet? How does Shidlovsky depict changes in the country, and particularly in the countryside, during the unstable months of rule of the Provisional Government? What was the impact of the Provisional Government’s June Offensive in WWI? Why didn’t the PG leave the war given its difficulty of ruling? Wednesday, March 2: The October Revolution (group E) Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 128-149 (“The Coup”) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 61-67 Kowalski, The Russian Revolution, 1917-1921, 72-76 (CR) Vladimir Lenin, “Marxism and Insurrection,” from The Lenin Anthology, 407-413 (CR) PREP: Was October a revolution or a coup d’etat? What degree of social support did the Bolsheviks have in deposing the Provisional Government and “all power to the Soviets”? What are Pipes’s positions on these issues and do you find them 9 persuasive? Why did Kerensky and the other radical parties fail to stop the Bolsheviks? How does Lenin justify the need for an insurrection? How did the Petrograd Soviet and the other radical political parties fit into Lenin’s political strategy? Friday, March 4: Explaining the Bolsheviks’ survival in power (no papers) Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 150-177 Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 87-92 Kowalski, The Russian Revolution, 105-109 and 216-219 (CR) Source on the nationalization of the state treasury (CR) PREP: How did it prove possible for the Bolsheviks—who had called for the planned Constituent Assembly to decide Russia’s constitutional future—to rule as a one-party dictatorship? Why did democrats, including democratic socialists, fail to mount an effective opposition to the October Revolution/coup? Why did the Bolsheviks wield terror against their opponents? Can such violence be justified by revolutionary ideology? Wednesday, March 9: the Russian Revolution in film: screening and discussion Note: if you do not attend the film screening you will need to make up this assignment by watching Eisenstein’s Ten Days that Shook the World on your own time and writing a two-page paper analyzing its portrayal of the Russian Revolution. Friday, March 11: no class take-home midterm due in box outside my office, 2 PM March 14-18: Spring break Part Three: War and Reconstitution, 1918-1921 Wednesday, March 23: Civil War (group A) Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 233-259 only Kowalski, The Russian Revolution, 118-123 (CR) Trotsky on the Red Army (CR) PREP: Why did the White” forces—which represented the Tsarist establishment and included many leading figures from the imperial army—fail to defeat the Bolsheviks? What were some weaknesses of the different centers of opposition to 10 the Bolsheviks: the Volunteer Army in the South, the states supported by the Czech Legion in the Volga area, and Admiral Kolchak’s forces in Siberia? Friday, March 25: War Communism and Red Terror (group B) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 72-83 Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 192-210 Sofia Volkonskaya, “The Way of Bitterness,” in In the Shadow of Revolution: Life Stories of Russian Women from 1917 to the Second World War, 140-157 (CR) PREP: What were the major components of War Communism? How did the countryside fit into the Bolsheviks’ plans? Was War Communism an ideological agenda or a tactical response to wartime conditions? How does Volkonskaya describe and explain the changes in Russian life during the Civil War? How do you explain the harsh measures meted out against those officially dubbed “former people,” citizens disenfranchised for their connections to the old regime? Wednesday, March 30: Spreading Revolution or recreating empire? The Russian Revolution Looks West (group C) Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 259-265 (on Jews during Civil War), 286-299 (part of “Communism for Export”) Isaac Babel, Red Cavalry (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003), “Crossing the River Zbrucz,” “A Letter,” “The Reserve Cavalry Commander,” “Gedali,” “My First Goose” (CR) PREP: Babel’s semi-autobiographical novel Red Cavalry depicts the Bolsheviks’ war against the newly created Polish state in 1920. The action takes place in Eastern Poland/Western Ukraine, a territory settled largely by Ukrainian peasants and Jewish city dwellers. Why were the Jews major victims of the Civil War period? Like Babel himself, the narrator was in a unique and highly complicated position as a Jew fighting in a Cossack unit of the Red Army. How did the Red Army interact with the local populations? What picture does Babel draw of the Red Army? Part Four: the Emergence of a New Civilization Friday, April 1: Anti-Bolshevik Revolution? Anarchists, bandits and others in 1920-1921 (group D) Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 93-102 Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 343-360 only 11 Excerpts on Makhno and the Krondstadt Rebellion in The Anarchists and the Russian Revolution, ed. Paul Avrich (CR) Quiz 3 in class PREP: Why and how did the Bolsheviks retreat from the radical agenda of war communism? Why did revolts of the Russian masses threaten to dislodge the communist regime in 1920 but not in 1917-1919? What was the role of Makhno’s army and how did it become so powerful? What drove sailors at the Krondstadt naval base—a pillar of Bolshevik power in 1917—to revolt against the party? Wednesday, April 6: no class: individual meetings on final paper projects Sign-up sheet to be distributed in class Friday, April 8: Library session in Collins Memorial Library 118 We will be meeting with history liaison librarian Peggy Burge to discuss research for your final projects. Wednesday, April 13: Culture and the family in the revolution (group E) Fitzpatrick, Russian Revolution, 84-87 Pipes, Concise History, 312-333 P. I. Lebedev-Polianskii, “Revolution and the Cultural Tasks of the Proletariat” September 16, 1918 (CR) Barbara Evans Clements, "The Birth of the New Soviet Woman," in Abbott Gleason, Peter Kenez, and Richard Stites, eds., Bolshevik Culture: Experiment and Order in the Russian Revolution (CR) PREP: How did avant-garde intellectuals see their place in the revolution? Is there a contradiction between the individual creativity of artistic creation and the politicized and (frequently) violent ethos of the revolution? Was the “New Soviet Woman” a new entity or a continuation of previous trends? What was the zhenotdel that Clements discusses? What were Lenin’s views on the “woman question”? What does the letter in the Soviet press tell us about the party’s view on women and the real experiences of women during the revolutionary period? Friday, April 15: Political culture and the succession to Lenin Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 107-119 chapter from Hiroyaki Kuromiya, Stalin: Profiles in Power (CR) PREP: Why did Stalin win the leadership contest in the USSR? As historians, should we focus on Stalin’s political acumen, Lenin’s decisions, the political 12 culture of the party, or some other factor? What does the Kuromiya chapter say about Stalin as a politician and a Marxist? Can you imagine a scenario in which some other Soviet leader might have defeated him in the struggle for power? Prospectus for final project due on Monday, April 18, 5 PM in folder outside my office Wednesday, April 20: The Soviet Union in the 1920s: Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog Mikhail Bulgakov, Heart of a Dog, entire PREP: Bulgakov was a Russian from Kyiv/Kiev from a religious family (his father was a priest at a Theological Academy). He fought in WWI and then served as a medical doctor with the Whites in the Civil War. He had difficulty getting published in the USSR due to the anti-Soviet nature of his convictions; Heart of a Dog (1925) was only published in Russia in the 1980s. He probably only avoided arrest in the 1930s due to the fact that Stalin liked one of his writings. For our discussion of Heart of a Dog, please find a passage or section in the text that you think is important. We will jump right into discussion by working off some of your ideas. A few questions: -how does Sharik appear as a dog and then in his later incarnation? Who was Chugunkin, whose organs are implanted in Sharik? -how does Bulgakov depict the interactions of Preobrazhensky with the housing committee? How does he resist their inroads on his apartment? Were such interactions possible in the NEP-era USSR? -How does Sharikov interact with Shvonder and the other communists? -is doctor Preobrazhensky a positive character or not? Are his inventions of positive value to society? What conclusions does he draw about his experiment? Friday, April 22: Drawing conclusions about the Russian Revolution Fitzpatrick, Russian Revolution, 1-14 Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution, 383-406 Quiz 4 in class PREP: Evaluate the extremely negative view of the Russian Revolution presented by Pipes. Based on our work this semester, do you see any flaws in his arguments? Pretend that you are a Bolshevik sympathizer (if you are not one already)—how would you attempt to refute the evaluation of the revolution presented here? Wednesday, April 27: no class (meetings in presentation groups) 13 Friday, April 29: group presentations Wednesday, May 4: group presentations May 13: final paper due at 12 noon in folder outside my office DISCUSSION PAPER GROUPS A Abendroth Smith, Melinda M. Burns, Colin D. Coe, Heidi E. B Engle, Shepherd C. Haley, Charlotte A. Katsui, Tianna K. C Koustmer, Delphine M. Molina, Mariana Puente, Nicolas D Purcell, David L. Robbins, Abigail B. Ruff, Andrew J. Stefan, Mallory K. E Taylor, Morgan K. Waterman, Rachel C. Whiteley, Calder H. Youngs, Eli M. Appendix: GUIDELINES FOR FINAL PAPER The final paper gives you an opportunity to investigate a single figure in the revolutionary period in Russia in depth. The choice of individual and topic is up 14 to you and I will not impose strict limits on it. You may want to focus on a politician or revolutionary, but you can also write about an artist from the period or, if you have sufficient source material for the task, a less exceptional, “common” individual. You may even choose to study a non-Russian who witnessed the Russian Revolution or participated in it, like the American John Reed. Chronologically, you may choose to study a figure involved in revolutionary currents before the revolutions of 1917 or 1905. Finally, you may want to write a collective biography of a group of individuals, like the imperial family during a specific period. The only hard and fast requirements are that the individual(s) was in Russia during the revolutionary period with the goal that your paper will speak to broader themes in the course. The goal of the paper is to write a biographical work, to tell the story of a life or a part of a life during an exceptional period of history. When historians write in a biographical idiom they take into account the context in which the individual in question acted. For this reason, your paper will ultimately say something about the history of the Russian Revolution. “The story” you choose to focus on might come in different forms, and will depend on your interests. You might choose to address a specific puzzle or problem in the biography of a major figure in the revolution that you have come across in our readings. Why did Trotsky join the Bolsheviks in 1917? Why did Miliukov join the Whites? What was the relationship between X or Y artist or writer and the Bolshevik regime? What was the nature of the relationship between Lenin and Krupskaia? If you do choose to focus on a major figure that has been heavily analyzed in the literature, you will need to focus on a specific problem or episode. There are no hard and fast rules about how many works you should consult. As a general rule of thumb, the paper should include at least five sources. These may include course readings but must extent beyond them. I encourage you to use primary sources like memoirs, which can give you a rich first-hand account of a life, but memoirs will not always be available in English. Partial list of possible figures (feel free to propose your own): Pavel Miliukov, Lenin in a specific period (ex. early revolutionary years) Trotsky “”, The young Stalin, Alexander Kerensky, Isaac Babel, Nestor Makhno, Nicholas II, Alexandra Kollontai, Mikhail Bulgakov, Semen Kanatchikov, Iulii Martov, Anton Denikin, Nikolai Bukharin, Anatolii Lunacharsky, Alexander Blok, Peter Stolypin, Alexis Babine, Alexander Kolchak, Victor Chernov, Lavr Kornilov, Feliks Dzerzhinsky, Maxim Gorky, John Reed, Peter Struve, Alexei 15 Brusilov, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, Grigorii Zinoviev, Fedor Dostoevsky, Anton Chekhov Specific suggestions for finding sources: -refer to the relevant articles of a subject encyclopedia, which give both context and suggestions for further reading. -consult the page for the course on the library website, which includes many collections of primary sources in English -A good and recent textbook or general study will also give historical context and, in the notes and bibliographies, clues about where to look for sources. -search for materials on WORLDCAT/ SUMMIT, historical abstracts, jstor etc. using different keywords. -ask me or history liason librarian Peggy Burge (pburge@pugetsound.edu) -search relevant search engines and databases for works written BY the figure you are interested in (author searches). There are a lot of memoirs by figures like Denikin, Brusilov, Witte, Kerensky, and countless others. GETTING STARTED: NOTES ON FINDING A GOOD PAPER TOPIC A topic for a research paper must be at least three things: interesting, significant, and feasible. Most of all, the topic should hold great interest to you. But this is not the end of the matter, because you are at the beginning of the research process—it isn’t yet clear what might come of your initial interest. So try to figure out in advance what might be interesting about the topic by generating preliminary questions. What problem or problems need to be solved? Why is this topic interesting to in the first place? What would an interesting paper on X or Y topic look like? The more questions you ask at the beginning of the process, the more smoothly research and writing will go. You have to know what you are looking for before you can find it. Significance means that the topic addresses a theme or problem of sufficient importance. For our course, this means that you should ask the following questions about a potential topic: How does my topic connect to broader themes in the history of the Russian Revolution? Why should interested readers care about this topic? These are the most important questions to ask for the purposes of our term paper. However, you might also want to think about what a paper on a specific topic might contribute to the state of knowledge. Some topics are better studied than others; deciding on a topic or argument that is poorly studied or poorly understood can be particularly rewarding. Have historians paid enough attention to this topic and drawn fruitful conclusions about it? For larger research projects, this becomes a critical issue. 16 A perennially difficult issue for term papers is feasibility. Is the question too complex to answer in the time you have to work on the paper? Do you have enough materials to explore the topic or issue that you are interested in? Most fundamentally: is there anything about your topic published in a language you can read? If you have to rely on secondary works (scholarship by scholars) instead of primary sources (eyewitness accounts) for your evidentiary base, are you comfortable doing that? Are the secondary sources substantial enough for the purpose? There is no one way to find a paper topic. But starting out with the clear recognition that interest, significance and feasibility are all necessary parts of the equation will help you with the process. If any of the three criteria are absent—in other words, if the topic seems dull, if it doesn’t speak to broader issues that are intellectually fruitful, or if it cannot be done with the time and library resources you can muster—then you should consider going with a different topic. Of course, the sooner you can reach such conclusions, the better! Finding a topic can happen by starting on any one of the three criteria discussed. For a term paper, interest and significance are usually the most important conditions that your project has to meet before you can be confident that your topic is a good one. You might strike gold by exploring your interests in general terms, perhaps by reading over course materials, a general textbook or a subject encyclopedia on the problem. Alternatively, you might also begin by searching for sources in a general area of interest to figure out what is feasible, and subsequently narrow down the topic by focusing on materials or topics that fit your interests. Regardless of which side of the equation you start from, finding a good research topic always involves thinking about interest, significance and feasibility together. PROPOSAL ASSIGNMENT Your proposal should have three headings: description, question, and sources. It need not exceed one single-spaced page. Description: This should be a single paragraph. In this section you should describe the project. You should address these questions (not necessarily in order): What individual and period are you exploring? Why do you think this will be relevant to the study of the Russian Revolution? Is this a feasible project that you can complete in the time you can allot to it? Question: 17 Try to describe what question your paper will be answering. What is your interest in the topic? What is the puzzle you are trying to solve? What is it you are hoping to discover by writing this paper? This can just be a sentence or two, but it is a very important exercise. By trying to put these thoughts in writing you will doing yourself a big favor. If you start research with questions in mind, you will reduce the risk of going off course: reading the wrong materials, avoiding dead ends, etc. Put more simply: to do research you have to know what you are looking for. Annotated Bibliography: In this section, list multiple sources you plan to use (using the Bibliography form of the Chicago system). There is no hard and fast number that is needed—the main thing is to show me that you have enough sources to carry out the project you propose. For instance, your paper might focus on a single work of literature or political tract; in this case, you might only list this work and a few secondary sources for context. Or your project might involve looking at several short sources, in which case your list should reflect that you are throwing a wider net, so to speak. Annotation means a short commentary after each of your sources. This can be only a sentence or few words, but it should convey WHY you think a specific source might be of use. For instance, “this book has information on Kollontai’s activities in the zhenotdel.” As you can tell, I do not expect you to have mastered specific sources at this stage—only to be gathering relevant materials and explain why they might be of use to you. 18