The Stamp Act of 1765

advertisement

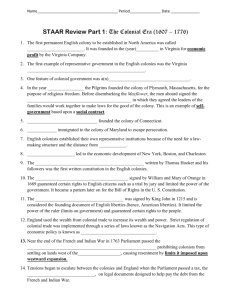

The Sugar Act of 1764 QuickTime™ and a On April 5, 1764, the British Parliament passed a modified version of the Sugar decompressor are needed to see this picture. and Molasses Act (1733), which was about to expire. Under the Molasses Act colonial merchants had been required to pay a tax of six pence per gallon on the importation of foreign molasses. The colonists tried to avoid the tax by smuggling in cheaper molasses and sugar from French colonies in the West Indies. This hurt the British West Indies market in molasses and sugar and the market for rum. The British Parliament decided it would be wise to make a few adjustments to the trade regulations. The Sugar Act reduced the rate of tax on molasses from six pence to three pence per gallon, but required that the tax be strictly enforced. The Act also listed more foreign goods to be taxed including sugar, certain wines, coffee, and cloth. The Act also tried to regulate the export of lumber and iron. As a result of the Act, the tax on molasses caused an almost immediate decline in the rum industry in the colonies. The combined effect of the new taxes was to sharply reduce trade with the French West Indies, which had been important trading partners for colonial products such as lumber, flour, cheese, and other farm products. The situation disrupted the colonial economy by reducing the markets to which the colonies could sell. Source: Adapted from http://www.ushistory.org/Declaration/related/sugaract.htm The Stamp Act of 1765 The Stamp Act was passed by the British Parliament on March 22, 1765. The new tax was imposed on all American colonists and required them to pay a tax on every piece of printed paper they used. Ship's papers, legal documents, licenses, newspapers, other publications, and even playing cards were taxed. The money collected by the Stamp Act was to be used to help pay the costs of defending and protecting the American frontier near the Appalachian Mountains (10,000 troops were to be stationed on the American frontier for this purpose). QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. The actual cost of the Stamp Act was relatively small. What made the law so offensive to the colonists was not so much its immediate cost but the standard it seemed to set. In the past, taxes and duties on colonial trade had always been viewed as measures to regulate commerce, not to raise money. The Stamp Act, however, was viewed as a direct attempt by England to raise money in the colonies without the approval of the colonial legislatures. If this new tax were allowed to pass without resistance, the colonists reasoned, the door would be open for far more troublesome taxation in the future. Few colonists believed that they could do anything more than grumble and buy the stamps until the Virginia House of Burgesses (the colonial Virginia legislature) adopted Patrick Henry's Stamp Act Resolves. These resolves declared that Americans possessed the same rights as the English, especially the right to be taxed only by their own representatives; that Virginians should pay no taxes except those voted by the Virginia House of Burgesses; and that anyone supporting the right of Parliament to tax Virginians should be considered an enemy of the colony. The House of Burgesses defeated the most extreme of Henry's resolutions, but four of the resolutions were adopted. Virginia Governor Fauquier did not approve of the resolutions, and he dissolved the House of Burgesses in response to their passage. Source: Adapted from http://www.history.org/history/teaching/tchcrsta.cfm The Boston Massacre, 1770 The Boston Massacre was a street fight that occurred on March 5, 1770, between a "patriot" mob, throwing snowballs, stones, and sticks, and a squad of British soldiers. Several colonists were killed in the fight. The presence of British troops in the city of Boston was increasingly unwelcome. A riot began when about 50 citizens attacked a British guard. A British officer called in additional soldiers, and these too were attacked, so the soldiers fired into the mob, killing 3 on the spot (a black sailor named Crispus Attucks, ropemaker Samuel Gray, and a mariner named James Caldwell), and wounding 8 others, two of whom died later. The British officers said they fired in self-defense. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. http://cache.eb.com/eb/image?id=65572&rendTypeId=4 Citizens of Boston called a town meeting to demand the removal of the British and the trial of the British Captain and his men for murder. At the trial, John Adams defended the British, leading to their acquittal and release. The Boston Massacre was an important event leading to the Revolutionary War. It led directly to the Royal Governor evacuating the occupying army from the town of Boston. It would soon bring the revolution to armed rebellion throughout the colonies. Source: Adapted from http://www.ushistory.org/Declaration/related/massacre.htm The Tea Act 1773 and Boston Tea Party The Tea Act would launch the final spark to the revolutionary movement in Boston. The act was not intended to raise revenue in the American colonies, and in fact imposed no new taxes. It was designed to prop up the British East India Company which was floundering financially and burdened with eighteen million pounds of unsold tea. This tea was to be shipped directly to the colonies and sold at a bargain price. Tea was important in colonial life – Parliament assumed the colonists would rather pay the tax than deny themselves a cup of tea. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. Earlier taxes were still in place, however, and the radical leaders in America found reason to believe that this Act was a maneuver to buy popular support for the taxes already in force. Colonists were angry that they were forced to pay taxes to the British Parliament when they had no representation. The direct sale of tea, via British agents, would also have undercut the business of local merchants. Colonists in Philadelphia and New York turned the tea ships back to England. In Charleston the cargo was left to rot on the docks. In Boston, the arrival of three tea ships ignited a furious reaction. The crisis came to a head on December 16, 1773 when as many as 7,000 agitated locals milled about the wharf where the ships were docked. A mass meeting at the Old South Meeting House that morning resolved that the tea ships should leave the harbor without payment of any duty (tax). A committee was selected to take this message to the Customs House to force release of the ships out of the harbor. The Collector of Customs refused to allow the ships to leave without payment of the duty. Stalemate. The committee reported back to the mass meeting and a howl erupted from the meeting hall. It was now early evening and a group of about 200 men disguised as Indians assembled on a nearby hill. Whooping war chants, the crowd marched two-by-two to the wharf, descended upon the three ships and dumped the cargo of tea into the harbor waters. Source: Adapted from http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/teaparty.htm and http://www.ushistory.org/Declaration/related/teaact.htm Coercive or Intolerable Acts, 1774 The British Parliament was angered by the Boston Tea Party and thought the colonists’ actions were disrespectful of British authority. Parliament disciplined the colonies and sought to control them more firmly by placing four "coercive acts" on Massachusetts and the other colonies. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. • Impartial Administration of Justice Act - allowed the royal governor of a colony to move trials to other colonies or even to England if he feared that juries in those colonies wouldn't judge a case fairly • Massachusetts Bay Regulating Act - made all law officers subject to appointment by the royal governor and banned all town meetings that didn't have approval of the royal governor • Boston Port Act - closed the port of Boston until the price of the dumped tea was recovered, moved the capital of Massachusetts to Salem, and made Marblehead the official port of entry for the Massachusetts colony. • Quartering Act - allowed royal troops to stay in people’s houses or empty buildings if barracks were not available. Colonists could not refuse to house British troops. These Acts were the harshest so far of all the Acts passed by Parliament. The Regulating Act aimed to curtail revolutionary activities. The closing of Boston's port alone cost the colony (and the American colonies as a whole) a great deal of money. The Quartering Act angered colonists who didn't want soldiers (especially Redcoats) in their houses. Source: Adapted from http://www.americanrevolution.com/IntolerableActs.htm and http://www.socialstudiesforkids.com/wwww/us/intolerableactsdef.htm The First Continental Congress The first Continental Congress met in Carpenter's Hall in Philadelphia, from September 5 to October 26, 1774. Carpenter's Hall was also the seat of the Pennsylvania Congress. All of the colonies except Georgia sent delegates. The delegates were united in a determination to show the colonists’ authority to England, but their goals and aims were not uniform at all. Pennsylvania and New York sent delegates with firm instructions to seek a resolution or compromise with England. The other colonies were defensive of colonial rights, but pretty evenly divided between those who sought legislative parity, and the more radical members who were prepared for separation. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. The first few weeks were consumed in discussion and debate. The colonies had always, up to this time, acted as independent colonies. The objectives of the Continental Congress were not entirely clear but a core set of tasks was carried out. The delegates agreed that they would communicate to the King and Parliament the grievances of the colonies. On October 14, they decided on a statement of principles common to all of the colonies and agreed to meet again the following year if England did not respond to their grievances. They also agreed not to import English goods, to establish ways throughout the colonies to enforce and regulate the resistance to England, and to keep the channels of communication open among themselves and with England. Source: Adapted from http://www.ushistory.org/Declaration/related/congress.htm Lexington and Concord, 1775 The decade-long political feud between the British government and the American colonists, determined to retain their rights as British subjects, came to a devastating climax as British regulars clashed with colonial militia and Minute Men on April 19, 1775 at Lexington, Concord's North Bridge and on the long, bloody road back to Boston. QuickTime™ and a decompressor are needed to see this picture. The British chose to march to Concord because it was an arms depot - the colonists had stockpiled weapons there. British troops had occupied Boston and were marching on Concord as they passed through Lexington. No one is still sure who fired first, but it was the "Shot Heard 'Round the World." Both sides opened fire, and the Americans were forced to withdraw. But they had slowed the British advance. By the time the Redcoats got to Concord, the Americans were waiting for them in force. The weapons depot was saved, and the British were forced to retreat, harassed by militiamen along the way. The skirmishes were preceded by Paul Revere's famous ride, warning the countryside: "The British are coming!" The fighting that began that day soon grew into a war for independence that lasted more than eight years. Many years later, Ralph Waldo Emerson used the phrase "the shot heard round the world" to describe the significance of this event. Source: Adapted from http://www.nps.gov/mima/historyculture/index.htm and http://www.socialstudiesforkids.com/wwww/us/lexingtonconcorddef.htm