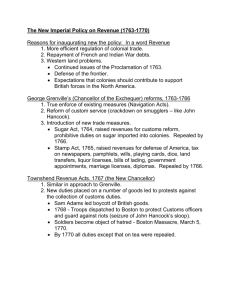

GEORGE GRENVILLE'S ACTS

advertisement

GEORGE GRENVILLE, TAXATION, and REBELLION There was a great need for England to generate revenue after 1763. The cost of the Seven Years’ War had increased Britain’s debt from approximately 73 million pounds to almost double that by the end of the war, most of which was shouldered by high interest loans. There was also newly acquired land and a newly imposed standing army of redcoats to support in America. English taxpayers alone could not cover the costs of winning the war, and maintaining an empire. With British countrymen already highly taxed and on the brink of revolt; it was the job of the first Lord of the Treasury, George Grenville, to bring Britain’s financial matters under control. His main goal was to pay off debts that the war accumulated, because The Seven Years’ War was more than a war of casualties; it was also a war that hit countries in their pocket. While Grenville argued that several of his imposed acts were his approach to increase revenue, decrease smuggling, and support the British soldiers, he mistakenly equated Parliament’s authority with the rights of the colonies, and ignored the individual liberties of the colonies. In peace time, the British land tax stood at three in a pound, but was raised to four in a pound to help bear the burden of war costs. Most people thought it would be reduced after the Peace in Paris (Treaty of Paris, 1763); however, this was not the case. In an attempt to generate more revenue, Greenville’s first plan of action was to leave the land taxes at four in a pound, but find a newer source of revenue from the American colonies. This was not an easy plan of action. Grenville understood Britain’s loss of revenue from the previous Molasses Act of 1733. What was originally meant to be a trade regulator, the Molasses Act of 1733 charged the colonists a tariff of six pence (a pence being approximately equivalent to a penny) on every gallon of molasses imported from the French and Dutch; while keeping England’s molasses duty-free (tax-free). This was because a large trade had grown between the New England and Middle colonies and the French, Dutch, and Spanish West Indian possessions. Molasses from the British West Indies, used in New England for making rum, was priced much higher than its competitors and they also had no need for the large quantities of lumber, fish, and other items offered by the colonies in exchange. The British West Indies in the first part of the 18th century were the most important trading partner for Great Britain, so Parliament was attentive to their requests. However, rather than acceding to the demands to prohibit the colonies from trading with the non-British islands, Parliament passed the prohibitively high tax on the colonies for the import of molasses from these islands. This threatened New England and the Middle colonies with economic strife or ruin, and at the same time opened the way for the British West Indians -- whom the continental colonists regarded as their worst enemies -to wax rich at the expense of their fellow subjects on the mainland. Largely opposed by colonists, the tax was rarely paid, and smuggling to avoid it was prominent. If actually collected, the tax would have effectively closed that source to New England and destroyed much of the rum industry. Yet smuggling, bribery or intimidation of customs officials effectively nullified the law. So, in accordance with Grenville’s suggestion, on April 5, 1764, Parliament passed a modified version of the earlier Molasses Act called the Revenue Act; which is commonly called the Sugar Act. Unlike the earlier tariff, the role of the Sugar Act was undeniably to generate revenue. It did so by lowering the tariff on imported molasses from six pence per gallon to three pence per gallon in hopes that merchants would legitimize and buy more British molasses. Grenville’s plan was to severely crack down on smugglers violating the Sugar Act who would get tried in British vice-admiralty courts instead of getting an American colonial jury—a first and demoralizing facet for Americans. The Sugar Act not only put a tariff on molasses but also listed many other foreign goods to be taxed including sugar, certain wines, coffee, textiles, and regulated the export of lumber and iron. The tax on molasses caused an almost immediate decline in the rum industry in the colonies. Unfortunately for Britain, the Sugar Act alone did not bring in enough revenue, so Grenville was charged with the creation of a new tax on the colonists. This new direct tax was made of 55 separate provisions and was known as the Stamp Act, passed in February of 1765. The Stamp Act required the colonies to pay a tax on every piece of printed paper. This included anyone who made a will, purchased a newspaper, received a college degree, or to simply taking a chance on playing cards. This tax was already in place in England, so Grenville and his Parliament assumed that it would be universally accepted and understood by the colonies. However, the taxing was not done through the Americans’ own representative assemblies, which led many colonists to believe that the small tax would lead to much larger taxes. The colonists began to perceive Grenville as a dictator trying to deprive them of their own liberties by unlawfully taxing their property; they expressed their discontent with riots throughout the streets and stamp burning. Although Grenville hoped to accomplish a control on public spending and to gain revenue to help pay for the continuing defense of the colonies, it ignited colonial opposition and led to the first effort by the colonists to go after Parliament. They cried out, “No taxation without representation,” in hopes the Parliament would discontinue the tax, but Parliament still would not repeal the Act. This led to the formation of the organized resistance group called the Sons of Liberty, led by Boston patriot Samuel Adams. Dedicated to independence, the group used often unsavory practices, such as “tarring and feathering” of British governors and officials. They felt that the colonies’ rights and grievances were enough to establish an independent country. The combined effect of the two acts reduced trade for colonists, disrupting economic, political, and social life in North America. The Stamp Act Congress, or First Congress of the American Colonies, was a meeting held October 7-25, 1765 in New York City. The first gathering of elected representatives from several of the American colonies to devise a unified protest against new British taxation, the extra-legal nature of the Congress caused alarm in Britain. This, along with economic issues created by protests and boycotts of British goods prompted the British Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act in 1766. Yet, the same day of the repeal, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act, which stated that Parliament could make laws binding the American colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” Grenville’s ill-judged measure to generate revenue for the benefit of the British Parliament led American colonists to believe they were no longer respected in England. Eventually, Grenville was asked to resign by George III, and was replaced by Lord Rockingham (and later, Charles Townshend). With Townshend’s leadership in 1767, Parliament passed a series of acts meant to put the colonists once again under the rule of the king and his ministers. The Townshend Acts imposed taxation on many colonial imports, including paper, glass, and tea. These taxes would be used to finance imperial administration in the colonies, in an attempt to undermine the authority and autonomy of American political groups. In addition, Townshend’s Parliament passed the Restraining Act, which suspended the New York assembly (self-government) in retaliation for their refusal to enforce the Quartering Act of 1765. The ongoing struggle throughout the colonies to control their own governments (and ultimately, destiny separate from their mother country) contributed to the spirit and organization of unity within the people. The revolutionary spirit was building among the American colonists. QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER: 1. Why did Parliament decide to place a higher tax on the American colonists in 1763? 2. Grenville knew that the Molasses Act was not successful in the colonies. What made him believe that his Sugar Act would work? 3. What economic and political effects did the Stamp Act have on the colonies? On Britain? 4. Why do you think the British Parliament and king were alarmed to hear about the Stamp Act Congress? 5. How did Townshend’s Acts differ from those of Grenville? Why does this matter?