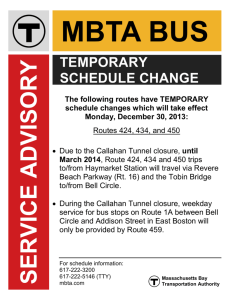

Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority

advertisement