ESTNESS V. PRAIRIE MEADOWS RACE TRACK AND CASINO

advertisement

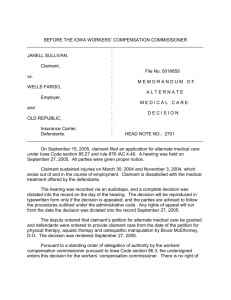

BEFORE THE IOWA WORKERS’ COMPENSATION COMMISSIONER ______________________________________________________________________ : CATHERINE ESTNESS, : : File No. 5024979 Claimant, : : vs. : : PRAIRIE MEADOWS RACE TRACK : AND CASINO, INC. : : APPEAL Employer, : : DECISION and : : EMC RISK SERVICES, LLC : : Insurance Carrier, : Defendants. : Head Note No.: 1108 ______________________________________________________________________ STATEMENT OF THE CASE Defendants appeal from the presiding deputy commissioner’s finding that claimant had sustained a cumulative workplace injury to her left shoulder that entitled her to healing period benefits and 10 percent industrial disability. Additionally, defendants contend that the presiding deputy by questioning claimant in the course of her testimony violated defendants’ due process rights by becoming an advocate for claimant and then not recusing himself. The record, including the transcript of the hearing before the deputy and all exhibits admitted into the record, has been reviewed de novo on appeal. In reviewing the transcript, the presiding deputy’s questioning of claimant was scrutinized in light of defendants’ claims of violated due process. When the questions to which defendants object are reviewed with consideration of the record evidence that had developed to that point in the hearing, the deputy’s questioning was not improper. Clearly, the questions, to which defendants object, were asked for purposes of clarification only and were not posed in any attempt to advocate for either party. The record evidence already had demonstrated that claimant had sought medical care for left shoulder complaints before she fell on December 26, 2007. It demonstrated that she perceived her left shoulder as impacted sufficiently by the December 26, 2007 fall that she sought additional emergency care for that shoulder on December 27, 2007. With that record, the trier of fact could legitimately infer that the ESTNESS V. PRAIRIE MEADOWS RACE TRACK AND CASINO, INC. Page 2 December 26, 2007 non work incident had aggravated the left shoulder condition either temporarily or permanently, such that inquiry as to claimant’s perceptions of the nature of any aggravation was appropriate, even though the better evidence in that regard would be expert medical opinion. Something neither party fully developed. FINDINGS OF FACT The claimant, Catherine Estness, was 58 years old at the time of the hearing. Her education consists of a high school diploma, where she was a “C” student. She also has a few community college course credits. Her prior work experience includes working for Olan Mills photography, working as a waitress at many jobs, check processing, and operating a restaurant. Claimant began working for defendant employer, Prairie Meadows Racetrack and Casino, in 2003 as a casino floor attendant. She continues in that position today. One of her primary duties is to pay out jackpots about 20 times per shift. This is a paperwork function that takes about 15 minutes per each payout or approximately five hours of each work shift. Claimant also is responsible for performing minor repairs on malfunctioning gambling machines, such as loading paper, freeing paper jams, etc. without requiring any tools. Some of the machines have light doors; some are heavier but have hydraulics. She has to push a cart carrying the paper supplies for the machines, as well as push chairs back into place, which she described as the major part of her job. She estimates she moves between 700 and 1000 chairs per shift. This is done on carpet, making it more difficult. (Transcript pages 29-30) Claimant uses her foot or her knee to scoot the chair in most of the time. She did testify that she would have to pick-up a chair to shoulder height two or three times per night, however. (Tr. pp. 47-48) Claimant received chiropractic care for left shoulder pain beginning in November, 2006, and continuing through April 2007. (Exhibit D, page 11) The chiropractic records do not show that claimant attributed this pain to her work. In February 2007, claimant’s mother broke her leg and claimant assumed her care until she was admitted into a nursing home in December 2007. This included helping her mother, who weighed 110 pounds, in and out of bed and bathing. Claimant took 55 days off work in 2006 under the Family Medical Leave Act, for anxiety, to take care of her injured husband, and to take care of her ill mother. (Exhibit K, page 1; Ex. H, pp. 26-40, 38) She did not attribute any of these absences to her shoulder. In 2007, claimant missed 59 full days, none of which were attributed to her shoulder. ESTNESS V. PRAIRIE MEADOWS RACE TRACK AND CASINO, INC. Page 3 On December 14, 2007, claimant sought medical treatment from ARNP Brandi Booth. Claimant alleges that day as the date of cumulative injury. Claimant reported left shoulder pain for the prior two years that disrupted her sleep and had worsened recently. She gave no history of specific injury and apparently did not mention her work duties as causing left shoulder pain. Testing showed claimant had decreased range of motion, pain, and weakness. (Ex. A, p. 12) Claimant again saw ARNP Booth on December 17, 2007, and again was diagnosed with left shoulder pain. An MRI was ordered and performed on December 21, 2007. The study was read as showing abnormal signal intensity in the rotator cuff region that may represent a partial cuff tear. (Ex. E, p. 17) The employer delivered a letter to claimant indicating she would be terminated if she did not provide medical justification for her absences in December 2007. Claimant provided a medical excuse from ARNP Booth. (Ex. A, p. 18) On December 26, 2007, claimant visited a bank in Pleasantville, Iowa, and stepped on a metal plate, which forcefully went down about three inches. Claimant testified this incident jarred her back, but she did not actually fall. Nevertheless, when she visited an emergency room in Knoxville, Iowa on December 27, 2007, she reported she had fallen in front of a bank and was having pain in her left shoulder, lower back, and left ribs. She was given x-rays and discharged with a left arm sling. (Ex. E, pp. 1-4) Claimant reported the bank fall to the bank and to her employer. On December 31, 2007, claimant sought treatment from Brandi Booth. ARNP Booth noted the December 26, 2007, incident at the bank. She pointed out that x-rays were taken, which were negative. She also noted she had seen claimant prior to the bank incident, and had ordered an MRI because she suspected claimant had a torn rotator cuff. Practitioner Booth referred claimant to an orthopedic surgeon, Ian Lin, M.D. (Ex. A, p. 14) Also on December 31, 2007, claimant’s husband called Gina Vitiritto, human resources manager for the employer, and stated claimant was in a lot of pain from her fall and was on a lot of pain medication and would not be able to return to work. Vitiritto told claimant’s husband claimant’s family medical leave had been exhausted. Claimant’s husband requested short term disability papers be sent. On January 2, 2008, Ms. Vitiritto called claimant and told her since she had used her FMLA leave, she would be placed on leave for up to one year, or until her doctor released her back to work. Claimant told Vitiritto she intended to sue the bank. (Ex. I, p. 3) Claimant saw Dr. Lin on January 16, 2008. He reviewed the MRI and concluded it showed a slight undersurface rotator cuff tear with some subacromial bursitis. Dr. Lin diagnosed left shoulder adhesive capsulitis, and felt claimant had a frozen shoulder. ESTNESS V. PRAIRIE MEADOWS RACE TRACK AND CASINO, INC. Page 4 Claimant could not recall any specific work injury and apparently did not report having had pain or difficulty performing any work duties. Claimant did report the December 26, 2007 fall and having left shoulder pain after that fall. She complained of difficulty with getting dressed, including putting on pants, putting her arm in a jacket, and putting on her bra. She reported that combing her hair was difficult. (Ex. B, pp. 4-5) On December 22, 2008, Dr. Lin opined claimant’s left shoulder condition was not work related, as claimant had denied any specific injury at work. (Ex. B, p.1) Dr. Lin appears to be basing his conclusion on the absence of a “specific injury”. Claimant is not alleging a traumatic injury, but rather a cumulative injury. ARNP Booth referred claimant to another orthopedic surgeon, Joshua Kimelman, D.O., whom she initially saw on January 22, 2008. He also diagnosed adhesive capsulitis with impingement syndrome of the left shoulder. Claimant did not report any left shoulder pain from work to Dr. Kimelman, only the jarring incident at the bank. Claimant had a cortisone injection and was referred for physical therapy for the frozen shoulder condition. (Ex. C, p. 4) Claimant continued to treat with Dr. Kimelman through June 2008. He did not feel she would have any permanent impairment or need any work restrictions, stating “I believe that she will ultimately sustain no permanent impairment as the prognosis for adhesive capsulitis in over 90% of people is for the symptoms to resolve”. (Ex. C, p. 1) Claimant did not at any time indicate to Dr. Kimelman that her left shoulder condition was related to her work. Dr. Kimelman has expressed no opinion as to whether claimant’s left shoulder condition relates to her work duties. ARNP Booth released claimant to return to work on July 11, 2008. Claimant returned to work for the employer on July 24, 2008. She resumed her regular duties with no work restrictions. Claimant testified that her frozen shoulder had resolved with physical therapy. On April 22, 2009, Robert Jones, M.D., conducted an independent medical examination of claimant. Claimant gave Dr. Jones a history of having done a lot of pushing in of chairs at Prairie Meadows from 2005 onward and of having noted intermittent left shoulder pain. She also stated that she thought her left shoulder pain was due to working overhead while working on machines at Prairie Meadows. (Ex. G, p.1) These histories to Dr. Jones, given more than 16 months after claimant first reported shoulder pain to Nurse Practitioner Booth, were claimant’s first and only medical histories relating her left shoulder complaints to any work activities. Claimant advised Dr. Jones that the bank incident had made her left shoulder pain temporarily worse, but apparently did not elaborate as to when she believed her pain had returned to its pre December 26, 2007 baseline. (Ex. G, p.1) ESTNESS V. PRAIRIE MEADOWS RACE TRACK AND CASINO, INC. Page 5 Dr. Jones found claimant to have decreased internal and external rotation of her left shoulder, as well as pain. He assigned claimant a rating of permanent impairment of three percent of the whole person under the AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment. Dr. Jones opined that claimant’s repetitious work at Prairie Meadows had caused her left shoulder condition. (Ex. G, p. 2) Claimant’s work duties at Prairie Meadows cannot properly be said to have been repetitive. Claimant performed a variety of work tasks. None of those tasks was done for a sustained time period. Work at or over shoulder level was done only occasionally. Chair moving duties generally involved effort with the feet or knees and not the shoulders. CONCLUSIONS OF LAW The first issue is whether the claimant sustained an injury arising out of and in the course of employment on December 14, 2007. The party who would suffer loss if an issue were not established has the burden of proving that issue by a preponderance of the evidence. Iowa R. App. P. 6.14(6). The claimant has the burden of proving by a preponderance of the evidence that the alleged injury actually occurred and that it both arose out of and in the course of the employment. Quaker Oats Co. v. Ciha, 552 N.W.2d 143 (Iowa 1996); Miedema v. Dial Corp., 551 N.W.2d 309 (Iowa 1996). The words “arising out of” referred to the cause or source of the injury. The words “in the course of” refer to the time, place, and circumstances of the injury. 2800 Corp. v. Fernandez, 528 N.W.2d 124 (Iowa 1995). An injury arises out of the employment when a causal relationship exists between the injury and the employment. Miedema, 551 N.W.2d 309. The injury must be a rational consequence of a hazard connected with the employment and not merely incidental to the employment. Koehler Electric v. Wills, 608 N.W.2d 1 (Iowa 2000); Miedema, 551 N.W.2d 309. An injury occurs “in the course of” employment when it happens within a period of employment at a place where the employee reasonably may be when performing employment duties and while the employee is fulfilling those duties or doing an activity incidental to them. Ciha, 552 N.W.2d 143. In this case, the question of whether claimant has suffered a work injury is closely related to the issue of whether claimant has shown a work injury is the cause of her current condition and the alleged periods of temporary and permanent disability. The claimant has the burden of proving by a preponderance of the evidence that the injury is a proximate cause of the disability on which the claim is based. A cause is proximate if it is a substantial factor in bringing about the result; it need not be the only cause. A preponderance of the evidence exists when the causal connection is probable rather than merely possible. George A. Hormel & Co. v. Jordan, 569 N.W.2d ESTNESS V. PRAIRIE MEADOWS RACE TRACK AND CASINO, INC. Page 6 148 (Iowa 1997); Frye v. Smith-Doyle Contractors, 569 N.W.2d 154 (Iowa App. 1997); Sanchez v. Blue Bird Midwest, 554 N.W.2d 283 (Iowa App. 1996). The question of causal connection is essentially within the domain of expert testimony. The expert medical evidence must be considered with all other evidence introduced bearing on the causal connection between the injury and the disability. Supportive lay testimony may be used to buttress the expert testimony and, therefore, is also relevant and material to the causation question. The weight to be given to an expert opinion is determined by the finder of fact and may be affected by the accuracy of the facts the expert relied upon as well as other surrounding circumstances. The expert opinion may be accepted or rejected, in whole or in part. St. Luke’s Hosp. v. Gray, 604 N.W.2d 646 (Iowa 2000); IBP, Inc. v. Harpole, 621 N.W.2d 410 (Iowa 2001); Dunlavey v. Economy Fire and Cas. Co., 526 N.W.2d 845 (Iowa 1995). Miller v. Lauridsen Foods, Inc., 525 N.W.2d 417 (Iowa 1994). Unrebutted expert medical testimony cannot be summarily rejected. Poula v. Siouxland Wall & Ceiling, Inc., 516 N.W.2d 910 (Iowa App. 1994). A treating physician’s testimony is not entitled to greater weight as a matter of law than that of a physician who later examines claimant in anticipation of litigation. Weight to be given to testimony of physician is a fact issue the workers’ compensation commissioner decides in light of the record of the parties develop. In this regard, both parties may develop facts as to the physician’s employment in connection with litigation, if so; the physician’s examination at a later date and not when the injuries were fresh; his arrangement as to compensation, the extent and nature of the physician’s examination; the physician’s education, experience, training, and practice; and all other factors which bear upon the weight and value of the physician’s testimony. Both parties may bring all this information to the attention of the fact finder as either supporting or weakening the physician’s testimony and opinion. All factors go to the value of the physician’s testimony as a matter of fact not as a matter of law. Rockwell Graphic Systems, Inc. v. Prince, 366 N.W.2d 187 (Iowa 1985) Phillips v. Covenant Clinic, 625 N.W.2d 714 (Iowa 2001) Claimant alleges a cumulative injury to her left shoulder from her work duties at Prairie Meadows Casino. Those duties consisted of doing minor repairs on gambling machines, pushing chairs back into place, and paperwork. Dr. Jones has concluded claimant’s repetitive work for the casino produced her left shoulder complaints. Unfortunately, the record evidence in its entirety does not support a finding that claimant performs any work for Prairie Meadows repetitively. Her duties are widely varied and do not involve sustained shoulder use. Additionally, the record evidence is that claimant only worked intermittently for Prairie Meadows in 2006 and 2007. She had other health issues and personal obligations that caused her to be absent from work in those years. Dr. Jones’ opinion as to causation is based on an inaccurate history and must be discounted. ESTNESS V. PRAIRIE MEADOWS RACE TRACK AND CASINO, INC. Page 7 Furthermore, claimant did not attribute her left shoulder condition to her work when she talked to her doctors. While claimant is neither a physician nor a lawyer and cannot be expected to understand the legal distinction between a traumatic work injury and a cumulative work injury, patients generally do know what activities produce or increase their experience of pain. Typically, if doing an activity is contributing to the development of an injurious condition, an individual will began to notice pain or other symptoms while doing the activity. Generally, patients contemporaneously report these symptoms to treating medical practitioners. Claimant’s failure to do so is at minimum troubling and decreases the weight that can be given her later history to Dr. Jones. Defendants point to claimant’s bank incident as an intervening cause of her shoulder condition; they also point to claimant’s activities as a caregiver to her elderly mother as a possible source of her shoulder pain. Further inquiry as to either’s role in claimant’s shoulder pain is not necessary, as claimant has not demonstrated that her left shoulder condition is a rational consequence of her work activities for the employer. Wherefore, it is concluded that claimant has not established a cumulative injury to her left shoulder that arose out of and in the course of her employment. Wherefore, the decision of the deputy is reversed. ORDER THEREFORE IT IS ORDERED: Claimant takes nothing from this proceeding. Claimant pays costs of this proceeding including the transcription of the hearing, pursuant to rule 876 IAC 4.33. Pursuant to an order of delegation of authority by the workers’ compensation commissioner pursuant to Iowa Code section 86.3, the undersigned enters this ruling for the workers’ compensation commissioner. There is no right of appeal of this ruling to the workers’ compensation commissioner. Signed and filed this 27th day of September, 2010. ____________________________ HELENJEAN M. WALLESER DEPUTY WORKERS’ COMPENSATION COMMISSIONER ESTNESS V. PRAIRIE MEADOWS RACE TRACK AND CASINO, INC. Page 8 Copies To: Ryan T. Beattie Attorney at Law 4300 Grand Ave Des Moines IA 50312 ryan@beattielawfirm.com Jane V. Lorentzen Attorney at Law 2700 Grand Avenue, Suite 111 Des Moines, IA 50312-5215 jlorentz@hopkinsandhuebner.com JEH/dll Right to Appeal: This decision shall become final unless you or another interested party appeals within 20 days from the date above, pursuant to rule 876-4.27 (17A, 86) of the Iowa Administrative Code. The notice of appeal must be in writing and received by the commissioner’s office within 20 days from the date of the decision. The appeal period will be extended to the next business day if the last day to appeal falls on a weekend or a legal holiday. The notice of appeal must be filed at the following address: Workers’ Compensation Commissioner, Iowa Division of Workers’ Compensation, 1000 E. Grand Avenue, Des Moines, Iowa 50319-0209.