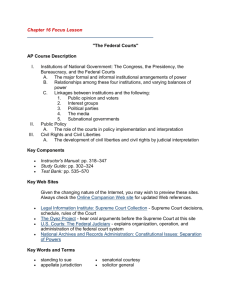

DDI09 Courts CP Generic

advertisement