Aural Devices

advertisement

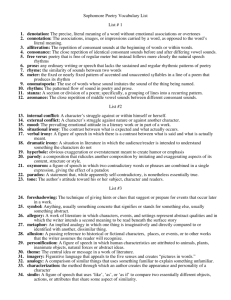

Some aural/sound devices (from http://conorschild.deviantart.com/art/Aural-Devices-A-GuidePart-1-118321847 Plosives are a sound produced by stopping the airflow in the vocal tract. This might be confusing, so it would help to list the plosive sounds in English: P B T K D and G (G is a sort of half-plosive, depending on the pronounciation--go vs. genie--but I didn't want to bring the International Phonetic Alphabet into this.) More accurately, the sounds are /puh/, /buh/, /tuh/, /kuh/, /duh/, and /guh/. If you make those sounds, your lips should come together then expand out, with an explosion of air. And there we go! Plosives are explosives. Simple! You may also feel your tongue move down with force as you make the sound, but not necessarily. It's a violent sound, and that's exactly where it's best used. Take Robert Browning's Porphyria's Lover: "...No pain felt she; I am quite sure she felt no pain. As a shut bud that holds a bee, I warily oped her lids: again Laughed the blue eyes without a stain. And I untightened next the tress About her neck; her cheek once more Blushed bright beneath my burning kiss: I propped her head up as before Only, this time my shoulder bore Her head, which droops upon it still..." I've gone overboard with pointing out the plosives, and yet I've probably not got them all. It should be no surprise then, that this poem is about the brutal murder of a young woman by a psychopath, who then goes on to talk to the corpse. Note as well the l's and n's used in this poem--while they aren't plosives in their own right, they become so much more violent in the atmosphere created by Browning: this isn't even the murder scene, and yet there's so much passion and energy behind it you can't help but hear the narrator's thumping heart and racing pulse. It's almost unbelievable, the ferocity created in those words--and of course, the nice thing about plosives is that the violent sounds created are so universal that many of the words used for that atmosphere are directly linked anyway--kill, stab, explode, thump, burst, death, gasp, etc, etc. Sibilance is the repeated use of sibilants in a poem. It's made by directing a jet of air through a narrow channel in the vocal tract towards the sharp edge of the teeth. That is, it's a hissing noise. The most common sibilant consonant is, of course, S, and also Z, SH and ZH (as in 'azure' or 'measure'). Sibilance is pretty much the polar opposite of plosive: it's silent, hushing and sensual. Here's three different examples of sibilance in poetry: "...I guess How you miss the English spring, the way A shower-cloud over a hillside spills Between sunlight and sunlight, slowly..." --Ted Walker, Letter to Barbados. "...Streams will swell and flow out, raging rivers, shower of thousand fires will patter and come together in a smooth and intense melody..." --Catherine Galfetti, springtime melody. "...The air-liner with shut-off engines Glides over suburbs and the sleeves set trailing tall To point the wind. Gently, broadly, she falls, Scarcely disturbing charted currents of air..." --Sir Stephen Spender, The Landscape near an Aerodrome. Each of the poets use the sounds to emphasis a different feeling: the quiet loneliness of abandonment, the sensuality of a lover, or the hushed refinement of an aeroplane interior. Notice as well how the first two poets use a similar image of a shower, linking the sounds and sight together--of course, an example of onomatopoiea. Closely related to sibilants are fricatives; in fact, sibilants are a sub-group of fricatives. The fricative consonants in English are F, V, TH (as in moTH) and H (as in Heat). They are made when the airflow is restricted, but is not stopped while making a sound. While they have a weak sound by themselves, when used in conjunction with sibilants they will accentuate the mood created. They can also work well with plosives, to create a hushed undertone to a violent mood. The final group of consonant sounds--for our purposes--are approximants. These are consonants that could be regarded as an intermediate between vowels and regular consonants: the sounds /wuh/, /yuh/, /ruh/ and /luh/ (think of the words towel, yes, furry and for l, two seperate sounds: Light or bottLe). Because of their close association with vowels, they work especially well with them to create a long vowel sound. Which gives us a good lead into the next topic! Long and Short Vowel Sounds Let's take another look at The Landscape Near an Aerodrome. The poem is about man's destructive nature and our pillaging of the natural world. It describes the descent of passengers on a plane, who in their lulled state compare the city they're landing at to the relaxing lands that they're returning yo. They realise with horror the destruction the city has caused to the landscape around it. I've highlighted the long vowel sounds used, but your accent may vary them slightly. "More beautiful and soft than any moth With burring furred antennae feeling its huge path Through dusk, the air-liner with shut-off engines Glides over suburbs and the sleeves set trailing tall To point the wind. Gently, broadly, she falls, Scarcely disturbing charted currents of air... "...Beyond the winking masthead light And the landing-ground, they observe the outposts Of work: chimneys like lank black fingers Or figures frightening and mad: and squat buildings With their strange air behind trees, like women's faces Shattered by grief. Here where few houses Moan with faint light behind their blinds, They remark the unhomely sense of complaint, like a dog Shut out and shivering at the foreign moon." This extract comes from different verses, and the difference between them is obvious. When the focus shifts to the town and it's industralised nature, there are far more shorter vowel sounds than the ones used in the description of the plane. What the poet has done here is an excellent example of Euphony and Cacophony. Euphony is a "pleasant combination of sounds; smooth-flowing meter and sentence rhythm give lines euphony; generally, lines with a high percentage of vowel sounds in proportion to consonant sounds tend to be more melodious." Cacophony, in contrast, is "'bad-sounding'; refers to the unpleasant discordant (cacophonous) effect of sounds or words; sometimes used by writers to give their writing a special effect; dissonance is the arrangement of cacophonous sounds in words or rhythmical patterns." By using long and short vowel sounds, there is a direct contrast built up between the two images of the poem, which lends itself well to the overall theme and message. Generally, a long vowel sound is created by the use of two vowels in a row (feel), a vowel follow by an approximant, especially double l's (tall, show), or two vowels around an approximant or sibilant (abuse, owe). A short vowel sound is usually made by a vowel followed by a plosive (hot), a single vowel after a fricative (felt, thigh), or before most double consonants (attack, end). However, there are many acceptions to each example--just sound out the words, and it'll all make sense. The vowels e and a lend themselves well to long sounds; i, o and u moreso to shorter sounds. Other than to create euphony and cacophony, the length of vowel sounds is a good way of artificially increasing pace. "...That are still courting-places (But the lovers are all in school), And their children, so intent on Finding more unripe acorns, Expect to be take home. Their beauty has thickened. Something is pushing them To the side of their own lives..." --Phillip Larkin, Afternoons In this poem, the poet starts off with masses of elongated vowel sounds ("Summer is fading://The leaves fall in ones and twos") for a euphonic feeling. But by the final verse, he begins to use shorter sounds, not just for their cacophonic effect but also to quicken the pace. He matches it with pauses for a disjointed rhythm, but the main effect is caused by the short vowel sounds--thickened, pushing, them--that hurtle the reader towards the pathos of the final line: how parents become less of a focus in life as their kids take over. Something similar happens in Letter to Barbados "...This morning I made A first cut of the grass since autumn. It smelt sweet in the sun, in the swathe Where I left it to dry. I fetched my gun And sought out a sickly dove and killed It clean, and let it warm where it fell..." In an otherwise tranquil and melodic poem, the quick and violent description of the dove's death comes as a surprise to the reader. By utilising shorter vowel sounds and hard consonants, this moment in the poem is almost hurried past--by both the narrator and the reader. It is also imporant to understand the different effects short and long vowel sounds will have on the words around them. Generally speaking, a short vowel sound will accentuate plosives; a longer vowel sound sibilants. For instance, 'spills' and 'spurts' both begin with 'sp'--a sound that could be either a sibilant or a plosive. But in the first case, the long vowel sound created by the double l hightens the sound of the s (both at the start of the word and the end) to give the word a sibilant sound as a whole. In the second case, the shorter vowel sound accentuates the p, giving it a consonant sound overall, and making it more violent. All of the sound units I've talked about (plosives, sibilants, long and short vowel sounds) will only work with repetition. Repetition, in fact, is the most important tool than any poet can use--not just in sound, but also rhetorically, and for themes and images. There are two words to describe the repetition of sound units: consonance, and assonance. Consonance describes the repetition of consonant sounds within a group of lines; assonance the repetition of vowel sounds. For example: "...Blown bubble-film of blue, the sky wraps round Weeds of warm light whose every root and rod Splutters with soapy green, and all the world Sweats with the bead of summer in its bud..." --Laurie Lee, April Rise Terminology of Aural Devices to look at once again: Sound Unit: Different parts of words that have a different auridotary effect. Also called a prosodic unit. Plosive: a consonant sound produced by stopping the flow of air at some point and suddenly releasing it; "his stop consonants are too aspirated." Examples of sounds include /buh/, /tuh/, /puh/, /duh/, /kuh/ and /guh/. Sibilant: a consonant characterized by a hissing sound (like s, sh or z). The repetition of this sound to create an effect is know as sibilance. Fricative: speech sounds produced by forcing air through a constricted passage (as 'f', 's', 'z', or 'th' in both 'thin' and 'then'). Approximant: a consonant sound made by slightly narrowing the vocal tract, while still allowing a smooth flow of air. Can be regarded as 'semi-vowels.' Include /wuh/, /yuh/, /ruh/ and /luh/. Vowel: A sound produced by the vocal cords with relatively little restriction of the oral cavity, forming the prominent sound of a syllable; A letter representing the sound of vowel; in English, the vowels are a, e, i, o and u, and sometimes y. A long vowel sound is often about 1 and a half times the length of a short vowel sound. Euphony: pleasant combination of sounds; smooth-flowing meter and sentence rhythm give lines euphony; generally, lines with a high percentage of vowel sounds in proportion to consonant sounds tend to be more melodious, or "euphonic". Cacophony: "bad-sounding"; refers to the unpleasant discordant (cacophonous) effect of sounds or words; sometimes used by writers to give their writing a special effect; dissonance is the arrangement of cacophonous sounds in words or rhythmical patterns. Assonance: the similarity or repetition of similar vowel sounds in word groups; examples include right-hive and pane-make; lake and stake rhyme, while lake and fate contain assonance. Consonance: the repetition of inner or end consonant sounds in word groups, without a similar correspondence of vowel sounds; similar to alliteration, except consonance does not limit the repeated sound to the first syllable. Onomatopoiea: the use of a word that suggests the sound it makes; creates clear sound images and helps a writer draw attention to certain words; examples include buzz, pop, hiss, moo, hum, murmur, crackle, crunch, and gurgle. Notice how consonance and assonance are concerned with familar sounds, not letters. For instance, "wraps round" is an example of consonance, and "swEArs with the bEAd" is an example of assonance. Notice also the alliteration of 'root and rod'. Technically speaking, alliteration is only the repetition of consonant sounds at the start of a word--not vowel sounds, or the same letter. However, many people will say that both of those count too. Assonance and consonance can often be used to create half-rhyme, para-rhyme, or if used within a line, internal rhyme. However, that is for the next guide. Until then, good luck writing! Meter: The rhythm of lines and of poetry. It is often counted as the repetition of certain units of rhythm, such as iambs, trochees, etc… Iambs: Unstressed to stress. Iambic pentameter is the typical mode of expression in Shakespearean plays, particularly during speeches, or addresses from nobles. Trochees: Stress to unstressed. Tyger tyger burning bright In the forest of the night What immortal hand or eye Can frame thy fearful symmetry Spondees: Two stressed, or two longs. This is often used to indicate passion, anger, stress, intensity. Note the use of spondees to break up the iambic lines of Hamlet’s soliloquy: O, that this too too solid flesh would melt Thaw and resolve itself into a dew! Or that the Everlasting had not fix'd His canon 'gainst self-slaughter! O God! God!