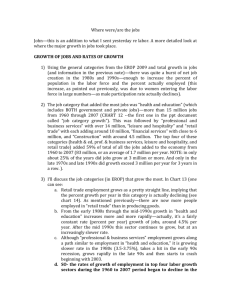

1 - World Bank

advertisement