3. Frustration of contract

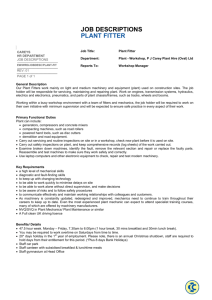

advertisement

Frustration of contract 高橋宏司 The principle of pacta sunt servanda. 1. Construction of contract Zweigert and Kötz, An Introduction to Comparative Law (1998) … the courts of England the United States are always careful to check whether on a proper construction of the contract one party may not have taken the risk of the possibility of performance. - Initial impossibility Sale of Goods Act 1979 s 6 Where there is a contract for the sale of specific goods, and the goods without the knowledge of the seller have perished at the time when the contract is made, the contract is void. Atiyah, Sale of Goods, p 70 It is submitted that if, on the true construction of the contract, it appears that the seller is contracting that the goods do exist, s. 6 will not apply and the seller will be liable for non-delivery. In appropriate circumstances a seller of non-existent goods may be held liable for damages on the basis that he has impliedly or even expressly warranted that the goods do exist. McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission (1951) 84 CLR 377 The defendants contracted to sell to the plaintiffs a shipwrecked tanker on a certain reef. After the plaintiffs had incurred considerable expenditure in preparing a salvage expedition, it was discovered that not only was there not and had never been any tanker, but also that the reef was non-existent. The High Court of Australia approached the case on the basis that the defendants were liable for breach of contract unless they could establish that there was an implied condition precedent that the ship was in existence. The court concluded that the only proper construction of the contract is that it included a promise by the defendant that there was a tanker in the position specified. - Subsequent impossibility Taylor v. Caldwell (1863) 3 B & S 826 The plaintiff hired the defendant's music hall for the promotion of concerts on future dates. 1 Before those dates the hall was accidentally destroyed by fire, and the plaintiff claimed damages for the loss he had suffered by reason of the non-occurrence of the concerts. The claim failed because the contract of hire was construed to contain an 'implied condition' that 'the parties shall be excused in case ... performance becomes impossible from the perishing of the thing without default of the contractor'. strict liability 2. Force majeure clause e.g. The Marine Star [1996] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 383 CA “Neither party shall be liable for any breach, delay or non-performance hereunder which directly or indirectly results from or is caused, in whole or in part, by revolutions or other disorders, wars, declared or undeclared, acts of public enemies, embargoes or other restrictions imposed by law, arrest, or restraint of officials, rulers or people, perils of the sea or other acts of God, accidents or navigation, or by breakdown or injury to ships, pipelines, machinery or other facilities of the seller or those from whom the seller obtained products purchased hereunder, used for production transportation, receiving, manufacturing, handling, or delivery of the products purchased hereunder, or the raw materials from which such products are manufactured, or other impairment or interference with sellers means of supply, transportation or other facilities, or by fires, storms, explosions, or other casualties, or by strikes, lockouts or restraint of labor, either partial or general from whatever cause, or if performance hereunder is hindered, delayed or prevented by, or would violate or controvert, any law, rule, order or request of government, federal, state or foreign, or any agency or representative thereof, or which directly or indirectly results from any cause beyond sellers or buyers control, whether such other causes be of the classes herein specifically provided or not. In the event of the foregoing, seller shall not be obliged to pro-rate product and/or deliveries hereunder nor shall seller be obligated to deliver from a terminal, use a berthing, loading or unloading facilities, type of carrier or manner of delivery other than those designated in the contract and in the absence of any such designation(s) those customarily used in the performance hereunder, regardless of whether a commercially reasonable substitute is available.” contra proferentem 3. Frustration of contract 2 Where events which occurred after the making of a contract have rendered the performance of the contract impossible, illegal or something radically different from what was in the contemplation of the parties when they entered into the contract, then the contract may be discharged on the ground of frustration. 4. Application to sale contracts cf sale of specific goods Sale of Goods Act 1979 s 7 Where there is an agreement to sell specific goods and subsequently the goods, without any fault on the part of the seller or buyer, perish before the risk passes to the buyer, the agreement is avoided. Sale of unascertained goods Blackburn Bobbin Co Ltd v Allen & Son [1918] 1 KB 540, 550 per McCardie J: … a bare and unqualified contract for the sale of unascertained goods will not (unless most special facts compel an opposite implication) be dissolved by the operation of [the doctrine of frustration]. Tsakiroglou & Co v Noblee Thorl GmbH [1962] AC 93 A quantity of Sudanese groundnuts was sold by contract at a price of £50 per ton c.i.f. Hamburg, and the vendor undertook to ship the goods in Port Sudan. After the conclusion of the contract, the Suez Canal was blocked owing to a war. Although the vendor could still have had the goods delivered to Hamburg via the Cape of Good Hope, the freight would have amounted to £ 15 per ton as opposed to £7 by way of the Suez Canal. Accordingly the vendor refused to load the goods and declared the contract at an end. The House of Lords upheld the arbitrator's award holding the vendor in breach. For this was a contract of sale in which it was indifferent to the purchaser by what route the vendor delivered the goods to Hamburg. The doubling of the freight was therefore regarded as unimportant. Zweigert and Kötz, An Introduction to Comparative Law (1998) If our very summary investigation of the question has suggested that English courts are less ready than German courts to hold that altered circumstances have brought a contract to an end, this is certainly attributable to the fact that the English courts are readier to meet the demands of international trade, for in the cases under discussion commercial men incline to keeping the contract on foot. This is shown, for example, by the fact that in the Suez Canal decisions we 3 have mentioned, the commercial arbitrators were all in favour of maintaining the contract; such a view in relevant commercial circles is obviously adopted as law by the English courts more readily than is usual in Germany. 5. Effect of frustration a. Automatic and prospective discharge of the contract The loss lies where it falls at the time of the frustrating event in accordance with the contractual allocation of the risk. Chandler v. Webster [1904] 1 K.B. 493 (CA) The plaintiff agreed to hire rooms from the defendant for the purpose of viewing the coronation procession of Edward VII. He further agreed to pay the sum of £141 on, or as soon as possible after, the signing of the agreement. He in fact paid only £100. When the procession was cancelled because of the illness of the King, the contract was frustrated. Held that the plaintiff was not entitled to recover the £100. The defendant was entitled to claim the remaining sum of £41 whereas his obligation to provide the flat was discharged. b. Restitutionary response under the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943 Restitution of money: s 1(2) Restitution of benefits in kind: s 1(3) eg 1. X contracted to make and erect machinery in Y's factory. Payment was to be made by monthly installment. After the conclusion of the contract, an accidental fire broke out and destroyed the factory, which frustrated the contract. By then, Y had paid ₤5000 (benefit) and X had spent ₤4000 (loss, wasted expenses). How much must X return to Y? s. 1(2) All sums paid or payable to any party in pursuance of the contract before the time when the parties were so discharged (in this Act referred to as "the time of discharge") shall, in the case of sums so paid, be recoverable from him as money received by him for the use of the party by whom the sums were paid, and, in the case of sums so payable, cease to be so payable: Provided that, if the party to whom the sums were so paid or payable incurred expenses before the time of discharge in, or for the purpose of, the performance of the contract, the court may, if 4 it considers it just to do so having regard to all the circumstances of the case, allow him to retain or, as the case may be, recover the whole or any part of the sums so paid or payable, not being an amount in excess of the expenses so incurred. eg 2. X contracted to make and erect machinery in Y's factory. Payment was to be made upon completion of the work. After part of the machinery worth £5000 had been erected, an accidental fire broke out and destroyed the factory, which frustrated the contract. But the machinery (benefit) was not damaged by the fire and Y could use it in another factory although it would not be as valuable as in the factory destroyed. Can X recover from Y any part of the £5000? s. 1(3) Where any party to the contract has, by reason of anything done by any other party thereto in, or for the purpose of, the performance of the contract, obtained a valuable benefit (other than a payment of money to which the last foregoing subsection applies) before the time of discharge, there shall be recoverable from him by the said other party such sum (if any), not exceeding the value of the said benefit to the party obtaining it, as the court considers just, having regard to all the circumstances of the case and, in particular, (a) the amount of any expenses incurred before the time of discharge by the benefited party in, or for the purpose of, the performance of the contract, including any sums paid or payable by him to any other party in pursuance of the contract and retained or recoverable by that party under the last foregoing subsection, and (b) the effect, in relation to the said benefit, of the circumstances giving rise to the frustration of the contract. eg 3. X contracted to make and erect machinery in Y's factory. Payment was to be made upon the completion of the work. After part of the machinery worth £5000 had been erected, an accidental fire broke out and destroyed both the factory and machinery (lost benefit), which frustrated the contract. Can X recover from Y £5000? BP v. Hunt (No. 2) [1979] 1 WLR 783 Held that, where the end product is destroyed by the frustrating event, the provider of the services has no claim under s. 1(3) because the value of the benefit (namely, the end product) has been reduced to zero by the frustrating event. eg 4. X contracted to make and erect machinery in Y's factory. Payment was to be made upon the completion of the work. After a part of the machinery worth £5000 had been erected, 5 an accidental fire broke out and destroyed both the factory and machinery (lost benefit), which frustrated the contract. By that time, X had spent ₤2000 to buy materials to build the remainder of the machinery (loss, wasted expenses). Can X recover from Y any part of the £2000? c. Should loss (wasted expense) be apportioned? BP v. Hunt (No. 2) per Goff J. The fundamental principle underlying the Law Reform (Frustrated Contracts) Act 1943 is "the prevention of the unjust enrichment of either party to the contract at the other's expenses." "… the Act is not designed . . . to apportion the loss between the parties." i. Arguments in favour of loss apportionment ii. Arguments against loss apportionment 6