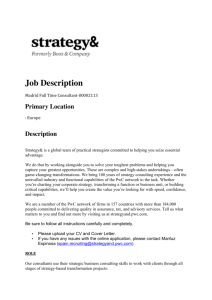

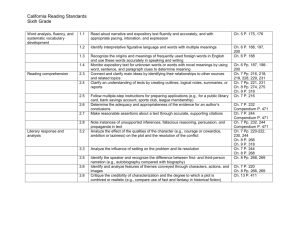

Learning Programme Management Systems

advertisement