Document

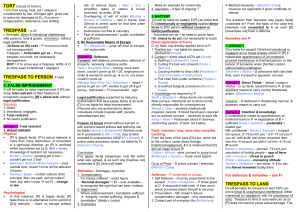

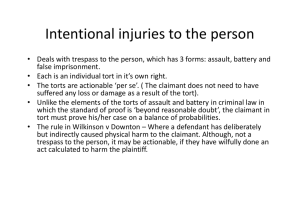

advertisement

Torts CAN – Fall 2007 Professor Peter Ramsay Q.C. Ildiko Tokes Tort law deals with obligations arising from membership in a community. Tort law allocates the loss(es) suffered by parties after the loss has occurred, based on a determination of fault. Categories of torts: - Intentional Torts - Negligence: failure to exercise duty of care - Strict Liability: despite lack of intent/negligence, law requires compensation Tort law deals with liability, not guilt, and results in compensation and damages, not punishment. Types of damages: - General: for natural result of wrongful act (ex: pain, suffering) - Special: specific expenses arising from wrongful act (ex: medical bills) - Aggravated: conduct of defendant aggravates the injury - Punitive: punishment and deterrence (esp. where little or no criminal recourse) Note: Canadian courts rarely award aggravated and punitive damages. 1. The Intent Requirement Meaning of Intent Constructive intent: conduct is treated as intentional even though results were not actually intended. Consequences are known to be substantially certain to follow. Garratt v. Dailey (1955) Facts: Child D pulls chair from under P. Action in battery. Trial judge decided no intent to injure; P appealed. Issue: Did D intend to commit battery? Held: Remanded to clarify D’s knowledge when he moved the chair. Analysis: It was not necessary to establish D had intent to injure, just whether he had knowledge that his actions had reasonable possibility of injuring. Did he know P would likely sit in the chair, before he moved it? Ratio: Intent to injure is not necessary to prove intent. Enough to show knowledge that actions have possibility of causing injury, and actions were intentional. Note: Age is only relevant in that the defendant must be shown to understand actions. (Tied to Capacity issue) Carnes v. Thompson (1932) Facts: D intended to hit someone else but struck P instead. Trial judge found for D because no intent to hit P. P appealed. Issue: Does P have claim in battery despite D’s did not intend to hit P? Held: Appeal allowed, new trial ordered. Analysis: D did not intend to hit P but did intend to strike an unlawful blow. Ratio: Transfer of intent is possible: if intent to commit battery exists, no need to show that the intent was to strike P. Smith v. Stone (1647) Facts: D was carried forcibly onto property; P brought action in trespass. Issue: Did D commit trespass if he was on P’s property involuntarily? Held: Judgement for D. He was not on property voluntarily, not liable. Analysis: He was carried, act not voluntary. Ratio: Trespass to land must be voluntary: element of VOLITION. Basely v. Clarkson (1681) Facts: D mistakenly cut P’s grass. Issue: Is there trespass if there is no intent? (Mistake) Held: Judgement for P; D liable for trespass. Analysis: D acted of his own volition which is requirement for trespass. Ratio: In trespass if the act can be proven and is not involuntary then D is liable regardless of intent, mistake, or ignorance. Gilbert v. Stone (1648) Facts: 12 armed men force D to enter P’s house and take gelding. Issue: Is duress a defence against trespass? Held: D liable for trespass. Analysis: Trespass was committed by his volition. Duress not a defence. It is better to allocate liability for loss to the person committing the trespass (albeit under duress) than to the completely innocent P. Ratio: Trespass must be voluntary and duress is not a defence. Note: Today a court would possibly find lack of volition in D’s act, if the threat was deemed serious enough. Mental Capacity: Youth Tillander v. Gosselin (1966) Facts: Infant D (less than 3) dragged infant P 100 meters, causing severe injuries. Action in trespass to person. Issue: Can the defendant show that his actions were neither intentional nor negligent? Held: Action dismissed, neither intention nor negligence. Analysis: No negligence: too young to exercise reasonable care, no capacity for reason. No intention because defendant lacked capacity to understand consequences of actions. Ratio: If D injures P, onus is on D to show that there was neither intention nor negligence. Pollock v. Lipkowitz (1970) Facts: 13 year old D threw acid on P, 12, causing severe burns. Issue: Were the defendant’s actions negligent and/or intentional? Held: For the P, although no punitive damages. Analysis: D was able to understand consequences of his actions; therefore he is responsible for the consequences if actions cause harm to someone else. Youth alone is not a defence. No punitive damages because no evidence of malice: impulsive act. Ratio: Age is not a defence. If D understands consequences of actions he is liable. Note: Parents also sued in negligence for failure to supervise. Court holds no negligence: no evidence that the parents knew the son had the acid. Mental Capacity: Mental Abnormality Gerigs v. Rose (1979) Facts: P, police officer, responded to report of man with gun threatening another person. P entered the house and was shot by D. Issue: Was the D mentally incapable (civil insanity)? Held: D liable for his act. Analysis: D intended to fire his gun at whoever came through, and understood this would cause injury. Even if he thought the officer was an intruder he still had intent and knowledge. Ratio: To prove civil insanity the D must prove that he was incapable of understanding the nature and quality of his acts. (No requirement to prove inability to understand right and wrong like in criminal cases). Note: Court also looked at whether officer was negligent: he was not, officers must take risks in the course of their duties, this is not negligence. 2. The Forms of Action: Trespass and Case Trespass on the Case: Original definition of trespass required direct injury to the plaintiff. “Injury flows naturally from the defendant’s act without the necessity of intervention by another independent factor” (Klar). Under that conception, a P had no cause of action if the harm was indirect: tripping on a log left on the road. Wanting to find someone liable for those situations, Courts created the cause of action of Trespass on the case: Injury as an indirect result of the defendant’s act. Negligent Trespass When negligence arose in tort law, the concept of negligent intentional trespass evolved. UK abolished it with Fowler v. Lanning. In Canada it continues to be good law (rarely used). Negligent intentional torts have been expanded beyond trespass (e.g. Battery). Cook v. Lewis: If P can prove direct injury by D, onus on D to prove both lack of intent and lack of negligence. Trespass (person or property) doesn’t require proof of damages. Today, intentional application of force is brought in battery (which is trespass on the person). Unintentional application of force can be brought under battery (using Cook v. Lewis) or negligence. Cook v. Lewis (1959) NEGLIGENG TRESPASS TO THE PERSON Facts: D hunting with another man. P was shot and brought action against both men. Trial found that P was shot by one of the men but unable to determine which one, verdict for D. Appeal by P. Issues: - Was P shot by one of the men and if so was it intentional or negligent? Who has burden of proof? - If held that one of the men is liable but unable to determine who, will P have remedy? Held: Court finds for P. New trial ordered. Obiter: judge decides that if at trial the jury can’t decide which did it, but one of them did, then both should be found liable. Analysis: It’s unfair that because we don’t know which man shot P, P has no remedy. Ratio: If P can show that he was the victim of direct application of force, he may plead under trespass to the person and onus is on D to show that he acted with neither intent nor negligence. Fowler v. Lanning (1959) ENGLAND Facts: P pleads that he was shot by D. Doesn’t claim intention or negligence. Issue: How should P frame his claim? Held: P must claim either intent (trespass) or negligence. Ratio: In English Courts plaintiff must chose one or the other cause of action. If unintentional, trespass is not available to the plaintiff, only negligence. Larin v. Goshen (1974) Facts: D, referee at wrestling match, makes unpopular decision leading to violence. As he leaves the ring he raises his hand to shield his head and causes injury to P. P sues using Cook v. Lewis. Trial judge found D shoved P but without intention; liable for negligence. Issue: Since there was direct application of force, was it intentional or negligent? Held: Appeal allowed. No intention, and no negligence. Analysis: Blocking his head behaviour of a reasonable person: not negligent. Ratio: Affirms Cook v. Lewis. Note: Court of Appeal normally doesn’t change finding of fact of Trial judge. 3. Battery and Assault Battery a.k.a. Trespass on the person Definition: A person who intentionally causes a harmful or offensive contact with another person is liable for battery. Elements: Intentional contact (no need for intended consequences) Objective standard of what is offensive/harmful: but not idiosyncratic Actionable without proof of damages Cole v. Turner (1704) Ratio: The least touching of another in anger is a battery. Fillipowich v. Nahachewsky (1969) FORCE MUST BE PROPORTIONAL Facts: Fillipowich finds cattle on his property and herds it to the pound with help of others. Nahachewsky and son (both Ds) see cattle and try to get it back to avoid pound fee. Fight breaks out with son, father hits Nahachewsky in head with a rock. Issues: - Was father acting in defence of son? - Was son also liable? - Did P provoke D and if so is it relevant? Held: Father was not defending son. Son not liable. Provocation is no defence. Analysis: No defence of son, as father landed blows before son began to fight. Hitting with rock was not proportional to the shoving. Son not liable, no joint tortfeasors. Driving cattle to pound wasn’t provocation; anyway provocation is not a defence to battery . Ratio: Force used in defence of self or other must be proportionate to force applied. Joint tortfeasors must have common purpose or act to be jointly liable. Bruce v. Coliseum Management Ltd (1998) PROV. CAN REDUCE DAMAGES Facts: P kicked out of D (nightclub) by bouncer, causing him to fall down stairs and break knee. Trial found for P but he was 30% responsible due to provocation. P appeals. Issue: Did bouncer use unreasonable force? Is provocation a defence? Held: Bouncer liable for battery although mitigated due to provocation. Analysis: Bouncer had legal right to eject P from premises. However he did so with unreasonable force (given size and experience). P was guilty of provocation but this is not a defence for the D, simply reduces damages. Ratio: Can be liable for legal activities if done with unreasonable force. Provocation is not a defence to battery although it can mitigate damages. Assault Definition: Assault is the intentional creation of the apprehension of imminent harmful or offensive conduct. Elements: D acted intentionally to create situation where P would be apprehensive of imminent physical harm Test for apprehension is subjective: even P has no ability to carry out threat, did D perceive a threat? Actionable without proof of damages I. de S. and Wife v. W. de S. (1348) Facts: D swung hatchet at P and missed. Issue: Can there be assault without physical contact? Held: Judgement for P. Ratio: The threat of harm, not the harm itself, is required for assault. Stephen v. Meyers (1830) Facts: D threateningly advanced towards P with a clenched fist. Was stopped before he could reach him. Issue: Is it an assault if D had no ability to execute his intention? Held: For P. Analysis: D was advancing with intent to strike a blow. Ratio: The threat of imminent harm or offensive contact, enough to cause apprehension in the victim, is enough to find assault. No need to be within touching distance, imminent need not be instant as long as it’s sufficiently imminent. Tuberville v. Savage (1699) Facts: D put hand on sword and said “If it were not assize-time, I would not take such language from you”. Issue: Is a threatening gesture an assault if the person declares s/he will not inflict harm? Held: No assault occurred. Analysis: D made it clear he would not imminently harm the P. Ratio: It is not assault to look threatening while specifying intent not to imminently harm. Obiter: Threatening gesture with no words: can be assault. Words alone: not an assault but can add to character of physical act. Bruce v. Dyer (1966) Facts: D tried to pass P on highway. P sped up and blocked him. D flashed high beams and tried to pass several more times. P stopped car, blocking D, got out of car shaking fists and advanced towards D, in threatening manner. D punched P in the face causing severe injury due to bone weakness. Issue: Is D liable for assault or does he have defence of self-defence? Held: Judgement for D. Analysis: P’s behaviour (blocking with car and waving fists) was assault. P had right to defend with force. D’s use of force was reasonable, he punched once: proportional to the situation, severity of injury was due to bone problems. Ratio: Force used in self defence against assault is a defence against a charge of battery if the force is reasonable (proportionate). Actively blocking someone’s way can be considered assault. Obiter: Judge would have instructed jury that if they had found D liable for battery, they would have to reduce damages to vanishing point due to provocation. M. (K.) v. M. (H.) (1992) Facts: Appellant (P) victim of incest from age 8 to 16. Profound effects on life. Sued and awarded damages but judge ruled statute of limitations had expired since she was aware of wrongdoing at least since age 16. Issue: Is incest breach of fiduciary duty? Is incest subject to statute of limitation and if so when does it begin? Held: Appeal allowed. Analysis: Incest is both tort of battery and breach of fiduciary duty. Limitation period for tort of battery/assault begins when victim reasonably capable of discovering the nature of acts and injuries, in this case during therapy as an adult. Ratio: Limitation period for assault and battery claims for incest begins running when victim knows of the injuries suffered. Incest is assault, battery and breach of fiduciary duty. Note: In BC limitation period for sexual misconduct no longer exists. Limitations Act sets out test for “reasonably discoverability”. Remoteness of Damage When assessing damages for intentional torts, the wrongdoer will be held responsible for all consequences, even those unforeseen and unintended. Bettel v. Yim (1978) Facts: P was lighting matches outside D’s shop. Shop caught fire but D didn’t see if P caused it. D shook P to extract confession, headbutting him in the process. P and his father brought action in assault (judge deemed it battery), general and special damages. Issue: Is D liable for all consequences of his actions, even those he did not intend? Were there 2 separate acts, the shaking of P and the accidental headbutt? Held: Judgement for P. Analysis: D was liable for all unintended consequences stemming from his intentional wrongdoing. Shaking P and head butting him were part of a “chain of actions” so D liable for all their consequences. Ratio: In a case of intentional wrongdoing, where the consequences are greater or different than what was intended, the defendant shall still be liable for all of them. Damages Holt v. Verbruggen (1981) Facts: D slashed P in hockey game, breaking his arm. Issue: Was the slash a battery or is there implied consent to some violence? If battery, does provocation by P mitigate damages? Held: Judgement for P. Compensatory damages mitigated by 50%. Analysis: Battery found because slash was more violent than could be implicitly consented to. Damages mitigated due to provocation. Ratio: Provocation reduces damages but is not a defence. Y. (S) v. C. (F. G.) (1996) Facts: At trial, P was awarded substantial compensatory, aggravated, and punitive damages for 700 incidences of sexual abuse suffered over many years. Issues: - Should trial judge have directed jury on “cap” on pain and suffering damages? - Was jury’s award inordinately high and therefore erroneous estimate of loss? - Should the substantial compensatory damages and publicity have eliminated or reduced the punitive damages? - Cross appeal: should Judge have instructed jury that D had breached fiduciary duty? Held: There should be no cap for sexual abuse. Damages reduced because the amount was wholly out of proportion with similar cases. Punitive damages reduced because of high stigma and high award for other damages, but not revoked. Ratio: No cap on damages for sexual assault, but the Court must consider similar cases. Punitive damages are to deter and must take into account other forms of punishment including criminal prosecution as well as other damages awarded. Note: Appellate courts will not disturb trial court’s decision regarding damages unless they are deemed outside of an appropriate range. If awarded by judge: “inordinately high”. If awarded by a jury: “wholly out of proportion”. Intentional Infliction of Mental Suffering Elements: Act or statement Calculated to cause harm, or with realization that harm would likely ensue Actual harm in the form of physical symptoms Wilkinson v. Downton (1897) Facts: D played practical joke on P, telling her that her husband had been in a serious accident. P suffered mental shock and serious permanent mental injury. Issues: What cause of action should the case be brought under and what must P show to recover damages? Held: Judgement for P. New intentional tort created (because neither fraud nor assault). Analysis: To claim intentional infliction of mental suffering, P must show: - Action by D – cases tend to be false statements, but can be acts. - Intention by D – intention to cause some kind of consequences, or substantial certainty that they would ensue - Harm caused to P – not necessary for D to anticipate all consequences Ratio: If someone intentionally commits actions causing psychiatric harm to another, they can be liable for intentional infliction of mental suffering. Note: Physical symptoms must be shown. Note: Under Cook v. Lewis, can be intentional or negligent. Clark v. Canada (1994) Facts: P was sexually harassed for years by officers and superiors in the RCMP and pressured to resign. She sued under several causes of action including intentional infliction of nervous shock. Issue: Did the RCMP officers’ actions meet the test for that tort and if so did it occur in the course of employment? Held: Judgement for P. The conduct met the test, and the RCMP was vicariously liable. Analysis: The tort of intentional infliction of nervous shock is: “extreme conduct calculated to produce some effect of the kind which was produced, and conduct producing actual harm i.e. visible and provable illness.” Ratio: The British tort as defined in Wilkinson v. Downton exists in Canada. Wainwright v. Home Office (2003) HOUSE OF LORDS Facts: Two Ps went to visit son/brother in jail for drug dealing. His visitors had to undergo strip search. Searchers did not follow regulations (fully naked, near uncovered window, one P’s penis was touched). Action for battery, invasion of privacy, and intentional infliction of mental suffering. Issues: Can the Ps claim under invasion of privacy? Alternately under Wilkinson v. Downton? Held: Judgement for P in battery only. Analysis: Battery found in the touching of the penis. No cause of action in invasion of privacy in England (nor Canada). Did not fall under Wilkinson v. Downton because lack of intent (just sloppy) and no actual psychiatric illness. Ratio: To claim intentional infliction of mental suffering, must show both intention and actual physical symptoms of psychiatric injury. No invasion of privacy tort. False Imprisonment What Constitutes Imprisonment or Arrest? Boundaries: Plaintiff must be restrained within boundaries, which can be real, conceptual, stable, moveable, small, or large. Not enough to be prevented to pass in one direction if free to pass in another direction. Force or Menace: Plaintiff must believe s/he is not free to leave the boundaries, whether due to physical force, threat, or perception of threat. Plaintiff is compelled to stay against his/her will. No touching is required. Elements: Total restraint (psychological or physical) within boundaries (real or conceptual) Intention to restrain (although negligent restraint my work under Cook v. Lewis) Actionable without proof of damages DEFENCES: Legal justification or consent Bird v. Jones (1845) Facts: D blocked a road for a boat race. P was prevented from passing through although not from turning back. Issue: Did D’s blocking of P constitute imprisonment? Held: Judgement for P. Analysis: Imprisonment requires total confinement within boundaries. If free to escape, not imprisonment. Blocking of bridge was only partial imprisonment. Ratio: Imprisonment requires total confinement within boundaries. Chaytor v. London, New York and Paris Association of Fashion Ltd (1961) Facts: Ps, employees of competing department store, entered D’s store to examine the merchandise. D detained Ps in a room and handed them to police. No touching, but D’s employees stood in the door and Ps said they felt they would be detained if tried to leave. Issue: Is there imprisonment without actual physical restraint? Held: For P. Analysis: D psychologically imprisoned Ps by making them feel that they must comply. They don’t have to try to escape to test it out. Ps were compelled to go to the police station thinking they had to answer charge made by D. D gave police misleading information, police not liable. Small damages awarded, innocence widely known. Ratio: Imprisonment does not require physical restraint, can be psychological. Can have false imprisonment even if confinement was for a short period. Note: If police act on false information given to them, they are not held liable. Murray v. Minister of Defence (1988) Facts: P arrested by armed soldiers at night, she was not aware that she was restrained. Issue: Is it necessary to be aware of imprisonment to bring action? Held: Judgement for P Analysis: Awareness of imprisonment not necessary, freedom from confinement is important personal freedom. Ratio: It is not necessary to be aware of imprisonment at the time it is committed. Actionable per se, without proof of damages. R. v. Whitfield (1969) Facts: Whitfield was convicted of escaping from lawful custody. He succeeded at appeal because he was not properly arrested. Appeal to SCC. Issue: What is the meaning of “arrest”? Held: Conviction affirmed. Whitfield was arrested. Ratio: There is no need for physical possession of the person for arrest to take place. Murray v. Minister of Defence (1988) HOUSE OF LORDS Facts: P was arrested by armed soldiers at night and did not know she was restrained. Issue: Is knowledge of imprisonment necessary to being action in false imprisonment? Held: Judgement for the P Analysis: Awareness is not necessary since freedom from confinement is such an important personal freedom. Ratio: Awareness is not necessary for false imprisonment. Actionable per se: no proof of damages. Legal Justifications: Enforcing the Criminal Law DEFENCE OF LEGAL AUTHORITY Statutes give individuals authority to do certain things, and if they commit a tort in the process it provides a defence. Covers a variety of offences. Linen: “Legislative authority allows the defendant to engage in conduct that would otherwise be tortious.” Applies to trespass to person/property and to false imprisonment. Challenging the defence of legal authority: - Challenge the constitutionality of the statute or provision - Use statutory interpretation to restrict the otherwise broad immunity Sources of legal authority: - CCC ss. 25, 29, 494, 495, 496: arrest with/out warrant, use of force - Offence Act – phone call - Police Act – ministerial and personal liability for torts If officer has no power to arrest under the statute cited, then no valid defence. Le Brun v. High-Low Foods Ltd (1968) Facts: P was shopping for groceries. Manager D had seen P before – he had odd shopping habits. D suspected P of shoplifting carton of cigarettes so he called the police. Did not confront P. Police stop P as he is driving away, and with his permission search his car. No cigarettes found. Action for false imprisonment against D and police. Issues: Was there imprisonment? Was the Constable legally justified? Was store manager legally justified? Held: Judgement for plaintiff against D grocery store. Police not liable. Analysis: Although imprisonment occurred: P felt he had no alternative but to submit. However Constable had reasonable and probable grounds due to information he had been given about suspicion of theft, under s. 25 and s. 435 of CCC. Manager of store is liable for imprisonment by police: had no justification, could not show facts creating reasonable suspicion in mind of reasonable man. Ratio: If D directs the police to imprison P without reasonable suspicion (objective standard) he shall be liable. NOTE: Issue of consent is discussed: a policeman in uniform asking someone to remain in a location while his vehicle is searched can not easily claim true consent due to psychological effect. Bahner v. Marwest Hotel Co. Ltd (1969) Facts: P, German immigrant, dines at hotel. Orders another bottle of wine at waiter’s suggestion shortly before closing. 10 minutes before closing time, waiter informs him he must finish the bottle by midnight. P refuses to pay for the bottle if he can’t finish it, and won’t drink it in 10 minutes. Manager summons Rocky the security guard, who tells P to pay or will call police. P still refuses to pay for 2nd bottle, pays for everything else, tipping generously. When he tries to leave, Rocky blocks him. Constable Muir arrives and tells him to pay for bottle or police will take him – Muir thought he could arrest for refusal to pay. When P refuses, he’s taken to jail where Justice of Peace tells Muir he can’t be charged. Muir then alleges drunkenness. Action in false imprisonment against hotel manager and Muir. Issues: Did P commit criminal act in not paying? Did D falsely imprison P? Did Muir falsely imprison P? Held: Judgement for P. Analysis: No criminal act in refusing to pay – may be civilly liable but not criminally. Rocky prevented him from leaving, without justification (no crime), so false imprisonment. Muir also liable for false imprisonment for arresting without warrant someone not committing an offence, and without telling him what he’s arrested for. Court rejected claim of intoxication. Hotel liable for imprisonment at hotel, not for Muir’s act. Muir’s responsibility takes over at the moment of arrest. Ratio: Intentionally detaining someone in the false belief that they committed a crime is false imprisonment. Mistake of law is not an excuse. NOTE: Aggravated damages against Muir for his conduct. Hudson v. Branford Police Services Board (2001) Facts: 2 officers went to P’s home to arrest him for failure to stay at the scene of an accident. They had reasonable belief that he was involved in the accident. Ds unlawfully entered P’s home without permission to arrest him. P spat on Ds. Pleaded guilty to assaulting police officer. Brought action in false imprisonment. Issues: Was Ds’ unlawful entry into the house justified under s. 25 or common law? Does P’s guilty plea to assaulting police officer bar his right to recovery? Held: Judgement for P. Analysis: S. 25 justifies using necessary force to arrest someone for reasonable belief they committed a crime. Doesn’t justify unlawful entry. Common law allowing trespass was changed by R. v. Feeney: warrantless entry only justified in hot pursuit or exigent circumstances. None here. Assault to which P pleaded guilty was a separate event and occurred after the imprisonment, does not bar P’s civil action. Ratio: Section 25 protects police officers if they make mistake of fact (if they acted under reasonable belief) but not for mistake of law (unlawful entry). Common law allows warrantless entry only in hot pursuit or exigent circumstances. Koechlin v. Waugh (1957) Facts: 2 young men stopped by police, walking home from movie. Asked for ID, P refused, scuffle broke out. Police used force to subdue and arrest P, not telling him why. Denied phone call. Police claimed they stopped the men because of a recent break-in by a man wearing rubber soled shoes (like P’s friend’s) and that they were “sauntering”. P’s subsequent actions led police to think he had or was going to commit a crime. Issues: Did police have reasonable grounds for suspecting P of a crime, allowing them to arrest P without warrant under CCC s. 495? (then s. 435) Held: Judgement for P. Analysis: Fell short of necessary level of suspicion required for arrest. Police could ask for ID but could not use force to compel him to ID since he was innocent of wrongdoing. P not required to submit to restraint unless told he was arrested. Police exceeded powers. Ratio: S. 495 CCC allows police to arrest without warrant if they have reasonable ground to believe suspect committed indictable offence. In such case Police must tell person why they are being taken into custody. NOTE: Person should not be held incommunicado. In case of unlawful arrest, resisting arrest is allowed (since it’s assault, not arrest) but not recommended. Abuse of Legal Procedure Aim: to balance benefits and remedies attainable through courts with the risk of abuse of the system. Malicious Prosecution Wrongful bringing of Criminal Charges Elements: a) Proceedings initiated by the defendant: a. Proceedings: criminal, bankruptcy – theoretically civil as well although doesn’t really happen. b. Initiated: first step in prosecution. Laying of an information is enough. c. Prosecutor: person actively instrumental in putting law into force. b) Proceedings terminated in favour of plaintiff: a. Acquittal, stay of proceedings, discharge at preliminary hearing.. c) Absence of both reasonable and probable cause: a. Nelles: “Honest belief in the guilt of the accused, based on a full conviction founded on reasonable grounds, the existence of circumstances which, if true, would reasonably lead an ordinary person” to believe guilt. b. Both objective and subjective: reasonable person would believe guilt, and prosecutor believed guilt. d) Malice or a purpose other than carrying the law into effect: a. Deliberate, improper use of the office of prosecutor for purpose other than the law: ill will, financial gain… b. More than recklessness or gross negligence e) Plaintiff must show damages to person, property, reputation: a. Person: fear of imprisonment, emotional harm b. Property: loss of income from missed work, cost of defence c. Reputation: due to criminal charges Crown has immunity but its agents do not (Nelles). Casey v. Automobiles Renault Canada Ltd (1965) Facts: P had company holding cars for D. As per their agreement, P sold some cars. Did not pay D immediately, tried to pay deposit and make arrangements for remainder. D filed information alleging theft, which became publicly known. D wrote to magistrate requesting withdrawal of charge before any action was taken against P. Issue: Did D filing information constitute prosecution? If so was it malicious? Held: Judgement for P. Analysis: Although matter hadn’t reached court, D had done all he could to initiate prosecution. Malicious: ulterior motive in mind, wanted to get his money. Damages proven, to reputation in car business. Ratio: Prosecution can commence when an information is laid against P. Watters v. Pacific Delivery Service Ltd. (1964) Facts: D was cop who arrested and charged P based on false evidence given to him by a 3rd party. P acquitted at trial. Issue: Did D charge P out of malice? Held: Judgement for D. Analysis: D had acted on false information, and held a reasonable (though false) belief in guilt. No malice found. Although enquiries at bank would have cleared P, there is both an objective and a subjective standard. Ratio: Plaintiff must show that D lacked reasonable and probable cause, carries subjective and objective standard. Honest mistaken belief leading to prosecution doesn’t meet the standard. Nelles v. Ontario (1989) Facts: P charged with 4 counts of murder in infant deaths at hospital where she worked. Discharged at preliminary hearing. Action against Crown, AG, and prosecutors. Failed at trial and appeal. Appeal to SCC. Issue: Are Crown, AG, and prosecutors immune from prosecution? Held: Partial judgement for P: Crown immune, AG and prosecutors are not. Analysis: Crown is immune by statute. AG and prosecutors not immune. Policy decision: there must be some recourse for citizens. Since malicious prosecution is hard to prove and Court dismisses frivolous pleadings, AG and his agents are able to execute duties without worry over liability. Ratio: Crown has absolute immunity against malicious prosecution action. AG and agents do not have absolute immunity. Norman v. Soule (1990) Issue: Can malicious prosecution action be brought for a civil action? Held: Action dismissed Analysis: Malicious prosecution action almost exclusively criminal since in civil action, P has recourse in defamation. Malicious prosecution in rare civil cases if aim was not justice. Ratio: Malicious prosecution is cause of action generally restricted to wrongful bringing of criminal charges with malicious motivation. Abuse of Process Wilful misuse or perversion of the court’s process for purposes extraneous to that which the process was designed to serve. Differs from Malicious Prosecution in that it is not necessary to show that the proceedings end in favour of the defendant or that there was a lack of reasonable and probable cause. Elements: 1. Defendant must use legal system 2. Defendant must have started process for a purpose other than that which the process was designed to serve a. Not enough to have a malicious motive if bringing action for the purpose for which it was designed. 3. Defendant must have done some definite act or made a definite threat in furtherance of purpose 4. Damages must have occurred Examples of improper purposes: - Force P into bankruptcy - Force P to sell property to D at reduced price - Tie up real estate deals in litigation - Blackmail Grainger v. Hill (1838) Facts: P owned ship, mortgaged to D under agreement that P would retain possession of the ship and be able to use it for profit. D wanted the boat immediately and had P arrested to force him to give up title to the boat to make bail. P lost profitable voyages. Issue: What action can P plead under? Held: Judgement for P and creation of new cause of action Analysis: D used authorities to extract the title to the boat. Ratio: Creation of the tort of abuse of process: intentional use of a legal process for a purpose other than what it was designed for. Guilford Industries Ltd. v. Hankinson Management Services Ltd. (1974) Facts: P, developer, hired D, builder, to construct buildings. D performed substandard work, causing P to refuse to have any more work done by him. D put a lien on the property to prevent further building on the site, and its sale. Issue: Was the filing of lien justified? Was it abuse of process? Held: Judgement for P. Analysis: Lien filed for purpose of preventing P from selling/developing land. Blackmail to induce settlement with D. Abuse of process. Ratio: D must make act or threat toward improper use of court for an action in abuse of process. Pacific Aquafoods Ltd. v. C. P. Koch Ltd. (1974) Facts: P brought action against D for supplying faulty machinery. D denied liability and brought counterclaim in abuse of process, claiming D was trying to prolong an action and did not have facts to support cause of action. P moved to strike the counterclaim. Issue: Is bringing a suit without properly supported cause of action an abuse of process? Held: Judgement for P: counterclaim in abuse of process stricken. Analysis: Even if P brought action with ill will or other motivation, that’s not enough for abuse of process. If P’s suit is devoid of merit that will come out in Court. Ratio: A claim in abuse of process must show that the suit was brought with an intent other than for which the process was denied. Ill will not enough. Misfeasance in Public Office Intentional acts of wrongdoing by public officials that have harmed the economic or other interests of private persons. Elements: a) Defendant is a public official b) Must show deliberate unlawful conduct or omission c) Defendant must have had awareness that the conduct was unlawful and likely to injure the plaintiff. Odhavji Facts: Someone shot and killed by police. During the investigation into the shooting it was alleged that the officers and Chief breached their statutory duty to cooperate with the investigation, impeding the investigation and causing distress, depression for plaintiff. Trespass to Land People are entitled to be free from physical interference, including property. Trespass is actionable per se: no proof of damage. P must be in possession of land, not owner: - life-tenant - renter - lessee Intention: No need for intention to commit trespass. Only volition to be on land needs to be proven – even if D didn’t know that it was a trespass. Interference: Direct, positive, physical interference must be shown, although no damage. This includes physically going on land, placing object on land, destroying something… Land: Surface, airspace, and subsurface. Turner v. Thorne (1959) Facts: D, deliveryman, mistakenly entered P’s garage and left packages due to confusing sign. P later tripped on the boxes and injured himself. Claim for trespass, and in the alternative negligence. Issue: Can P succeed in trespass although it was not intentional? Can D use defence of mistake of fact? If D is liable for trespass is he responsible for unforeseen, indirect damages? Held: Judgement for P Analysis: P could succeed in trespass but decision given in negligence: trespass doesn’t require intent. Ratio: Lack of intention or mistake of fact are not defences to trespass. Trespassers liable for all consequences of their trespass. Placing object on land can be trespass. Costello v. Calgary (1997) Facts: D, Calgary, expropriated P’s land under Expropriation Act and held it for some time. Expropriation later deemed unlawful. P sued in trespass. Issue: Was the city’s possession a trespass? Held: Judgement for P Analysis: Trespass occurs when expropriation is invalid. That it was unintentional is unimportant: defendant intends to conduct itself in a certain manner and exercises its volition to do so. Consciousness of wrongdoing irrelevant. Ratio: Trespass occurs whether or not the trespasser intends to interfere with the property rights or not, so long as s/he acted of his/her own volition. Anderson v. Skender (1994) Facts: P had 2 trees whose bases were completely or substantially on his property but trunks extended over D’s land. D cut the trunks hanging onto his property, at a point that was on P’s property. D destroyed the root systems of the two trees as well as a third. The 2 trees died, the third was not seriously affected. Issues: Is a property owner entitled to trim his neighbour’s trees that extend on his land? Held: Judgement for P for 2 dead trees, no damages for the surviving tree. Analysis: D committed trespass by cutting the trees over P’s property. (Onus on D to show that he could have cut the trees without trespass). Trimming trees where they overhang onto your property is not a trespass. Since D had not crossed the property line to destroy the roots of the tree, this was not a trespass. Ratio: It is necessary to physically cross onto P’s property to commit a trespass. Nuisance says the owner of land is entitled to cut branches or roots if they extend over the property line. Defences to Intentional Torts P must prove all the elements of the intentional torts on BOP: onus on P. Failure to prove the elements means P loses. Note: burden can shift in Cook v. Lewis cases. When it comes to the defence the onus always on D. Categories of defences: - Defences to the core of the case: o Denying element of P’s case has been proven o Can use established defences to rebut elements of P’s case Ex: if P argues wrongful interference with his person, D can raise lack of capacity, lawful authority, or consent o Defence must be established by bringing evidence - Policy justifications for D’s behaviour: o Battery is allowed in cases of self-defence; trespass to save from drowning - “False” defences: o Provocation o Contributory negligence Consent Volenti non fit injuria – “No harm is done to he who consents” EXPRESS CONSENT: If P explicitly consents there can be no tortious act. Mulloy v. Hop Sang (1935) Facts: D injured hand in car accident. At local hospital he gave express directions to the doctor (P) not to amputate his hand since he wanted to see a different doctor. D anesthetised P and examined hand; determining that amputation was necessary, he proceeded. P brought claim for his medical fees, D counterclaimed in trespass to person for damages for his artificial hand and lost wages. Issues: Can P succeed in his claim for medical fees since medical opinion agreed the operation was necessary despite lack of consent? Is D entitled on his counterclaim in battery and if so, to what extent? Held: Judgement for D. Action for medical fees dismissed, counterclaim allowed. Analysis: D had expressly refused the amputation so P did not have consent to do the operation: he was not hired to do the work and should not be paid. D succeeds entitled in battery due to lack of consent. Ratio: Express refusal must be complied with even at the refuser’s peril. Malette v. Shulman (1990) Facts: P badly injured in car accident and unconscious, rushed to hospital, attended by doctor D. P had card expressing beliefs as Jehova’s Witness and instructions not to receive blood transfusion under any circumstances. D knew of the card but performed transfusion. P recovered and brought action against D in battery. Issue: Were the instructions on the card valid? Could D ignore the card due to the emergency? Was D entitled to ignore the card since he could not get “informed refusal” after explaining the consequences of refusal? Held: Judgement for P. Analysis: Express refusals for treatment cannot be ignored even in emergencies. Unqualified card no different than a direct refusal of a conscious person. Not logical to assume card not valid or that P would change her mind. Ratio: Express refusal to consent to a battery must be complied with even in an emergency. Informed consent does not translate to informed refusal. **EXCEPTION TO CONSENT: MEDICAL EMERGENCY: Marshall v. Curry (1933) Facts: P asked doctor D to repair hernia. During the operation D deemed it necessary to remove a diseased testicle. P brought action in negligence (failure to disclose that he would remove the testicle) and battery (removal of testicle without consent). Issue: Was D required to get consent from P? Held: Judgement for D Analysis: D had no way of knowing, before the operation, the condition of the testicle. No negligence in not disclosing it. D acted in P’s interest and for protection of his health and life and it was not possible to obtain consent before proceeding. In emergency the surgeon’s duty is to save the life or preserve health. Ratio: In an emergency situation a doctor is privileged to provide medical attention to save the life or preserve the health of the patient if it is impracticable to obtain consent from the patient or substitute decision maker. Informed Consent In medical procedures two interests may conflict: - Doctor’s duty to provide care - Patient’s right not to have his body interfered with without consent Since most laypeople lack knowledge of medicine to make a proper decision, it is the duty of doctors to properly inform patients of the procedures available and their possible consequences in order to get informed consent. Battery occurs when there is no consent. Negligence occurs when the doctor has been negligent in not fully informing the patient of outcomes and consequences when obtaining consent. P needs to show: - D did not inform P of all relevant aspects of the procedure: RISKS and ALTERNATIVE treatments - If P had been fully informed he would not have consented - causation - Damages must be shown (unlike battery) Also separate tort for negligent performance of the procedure (medical negligence) Halushka v. University of Saskatchewan (1965) Facts: Two medical researchers (D) paid P $50 to perform test on him. Ds did not tell P that the test was for a new anesthetic, nor that catheter would be inserted in his heart. P suffered cardiac arrest from which he recovered. Action in negligence and trespass. Issue: Given P’s agreement to do the test, did he consent? Held: Judgement for P. Analysis: Although P agreed to the test he was not fully informed of all the procedures and could not make informed consent. Ratio: Before medical procedure can be performed, s/he must be fully informed. Note: Old case which today might be decided on negligence (informed consent) or battery (operation was not consented to). The law has changed. Reibl v. Hughes (1980) Facts: P had surgery to remove blockage from carotid artery. Right after operation he suffered a stroke. Claimed he had not been given proper information before surgery, no informed consent. Issue: Did D give P proper information allowing him to make informed consent? Held: Judgement for P Analysis: Court restored judgement for negligence: D had acted negligently by not explaining risks. In determining causation, Court chooses modified objective test: whether a person in P’s shoes would have opted for the surgery given the correct information. In this case a reasonable person in P’s position would not have consented. Judgement for battery not allowed: can only exist when patient has not consented at all. Ratio: In medical procedure cases battery will be the action if P has not consented to the procedure, negligence if P has not been given enough information to give informed consent. Causation for negligence claims for lack of informed consent will be determined on a basis of a modified objective test: would a reasonable person in P’s position have opted for the procedure if properly informed. Factor in P’s particular fears if reasonably based. (Reibl modified objective test) Arndt v. Smith (1997) Facts: P brought action against doctor D for costs of raising disabled child. Claims if D had informed her of the risks involved with chicken pox during pregnancy she would have aborted. Issue: Would P have aborted her child if D had fully disclosed the small risks? Held: Judgement for D. Analysis: Court applied Reibl Test and found that a reasonable person in P’s shoes (wanted children, distrustful of medicine) would not have aborted the pregnancy if fully informed. Ratio: The Reibl Test for causation should be used for determining whether the lack of disclosure should result in liability for medical negligence: modified objective. Van Mol (Guardian ad litem of) v. Ashmore (1999) Facts: P, 16 at the time, had surgery for narrow aorta and became paralyzed. Sued for negligence for poor performance of surgery, and negligence in not giving proper information to get informed consent. Issue: Was D negligent in not getting informed consent? Should he have obtained consent from P, minor, or her parents? Was D required to inform that person of alternate surgeries and additional safeguards? Held: Judgement for P: only for negligent failure to get fully informed consent. Analysis: Surgery itself was not negligently performed. D ought to have gotten informed consent from P, who was intelligent enough to give informed consent: no set age for consent, if patient has sufficient mental capacity/maturity. Should have discussed risks and alternate treatments. Reibl Test: a reasonable person in P’s circumstances, if properly informed, would have opted for the safeguards and on BOP the paralysis would not have occurred. Ratio: If a minor is intelligent and mature enough to make decisions about his/her welfare, only he/she can give informed consent to medical procedures, not parents. Reibl states that a doctor has a duty to discuss with a patient alternative methods of surgery and the risks and advantages of each method. Statute: Infants Act s. 17. Maintains common law rule of infant consent. Improperly Obtained Consent Norberg v. Wynrib (1992) [SCC] Facts: P became addicted to pain killers and her doctor, D, learned of the addiction. He only gave further prescriptions if she performed sexual acts with him. P brought action in battery for sexual assault. D claimed implied consent. Issue: Was there implied consent by P? Held: Judgement for P: battery due to lack of meaningful consent. Analysis: Meaningful consent is free, full, and informed. Failure to resist/protest may be consent but it must be genuine. Consent is not a defence if it is obtained through force or threats of force, fraud, or while the other party is under the influence of drugs or alcohol. (None of these was the case). Court extends the concept and says there can be no consent when there is a great imbalance of power between the two parties. D knew P was vulnerable and he was in a position of power to provide her more drugs or help her. He abused this power while getting the consent. Rejects application of ex turpi causa (no cause of action in tort arising from P’s illegal action). Ratio: Consent is not properly obtained if got through: force/threats of force; influence of drugs/alcohol; fraud; imbalance of power between parties. Test for power imbalance: inequality between parties AND exploitation of that inequality. Self-Defence and Defence of Others Self defence is “defence, not counter-attack”: - reasonable force must be used: reasonably necessary, and proportionate to the harm - can be pre-emptive if imminent harm is feared Cockroft v. Smith (1705) Facts: D bit off the end of P’s finger in the course of a fight. Action in mayhem (a cause of action in trespass) Issue: Can D use self-defence? Held: Judgement for P Analysis: D’s actions in defence were not proportionate to P’s actions Ratio: Force in self-defence must be proportionate to the harm it is trying to defend. MacDonald v. Hees (1974) Facts: Late at night, P went to D’s hotel room and entered, thinking D had invited him in. D violently ejected P and injured him. P brought action in battery, D pleaded self-defence and use of force against unlawful entry and invasion of privacy. Issue: Does D have a defence of self-defence? If so did D use reasonable force? Was D justified in using force because of unlawful entry and invasion of privacy? Held: Judgement for P Analysis: Use of force not justified and force was excessive. D was much larger and did not feel threatened by P so no expectation of harm. D may not forcibly eject P unless P has entered forcibly or P has been asked to leave. Ratio: Force in self-defence must be reasonable: necessary and proportionate. Trespasser may not be forcibly ejected unless has been asked to leave or has entered forcibly. Gambriell v. Caparelli (1974) Facts: D arrived to the scene (alley) to find P seemingly strangling D’s son after a minor car accident. D struck P in the shoulders and head with a garden fork. P sued in assault. D claimed defence of her son. Issue: Was D acting in defence of her son? Was the force reasonable? Held: Judgement for D Analysis: D was acting in defence of her son. Use of force reasonable: if P could overpower the son, then D would be of little use without a weapon. No excessive force: P suffered only lacerations. Ratio: Force may be used in defending a third party provided it is reasonable: necessary and proportionate. Business Torts - Unlawful interference with business interests Conspiracy Intimidation Passing off Deceit Inducing breach of contract Overlap with other areas of law like contracts. Reason for different types of law is that they seek to achieve different purposes. While contract law aims to maintain economic and business certainty, business torts aim to uphold social purposes, compensation, deterrence. Deceit Elements: - False representation made by defendant - Knowingly - With intention to deceive the plaintiff - Which materially induced the plaintiff to act resulting in damage Pasley v. Freeman Facts: D made statements that another person, Felch, was solvent. P wasn’t able to collect from Felch as he was insolvent. P sued D for the false statement. Held: Judgement for P Ratio: A person can be liable for fraudulent statements even though the representor had nospecific interest in the matter, nor was in collusion with the party that did. Derry v. Peek Facts: D asserted that they could get steam engines. Issue: Did D have reasonable belief that they could get steam engines? Ratio: Reasonable belief must be demonstrable with evidence. Sidhu Estate v. Bains Facts: D deceived P, Mr Bandar, executor of the estate of his deceased sister. D induced P to invest in his company by claiming he and another man had already invested 600K and 340K. Bandar had already succeeded in another case against the D in deceit. Bandar tells his sister Mrs Sidhu that the men have invested, so she invests. Issue: Is D liable for Bandar’s statements to Mrs Sidhu? Held: Judgement for P Analysis: D was in the room when the conversation occurred, and stayed silent in the face of the deception. Ratio: Can commit deceit by staying silent. Damages: Courts have followed different approaches. Some have looked at what infusion of money would be needed to make the business decision profitable, while others may accord no damages, if actual value is similar to the misstated value. Unlawful Interference and Inducing Breach of Contract Debate about unified tort theory: UK sees them as separate torts (as in OBG) but Canadian Courts have tended to see them as different aspects of the same tort. Lumley v. Gye Facts: Famous opera singer in the 1800s has exclusive contract with Queen’s theatre. A competing theatre induces her to breach her contract and perform at both theatres. Ratio: Establishes the tort of inducing breach of contract. Inducing Breach of Contract: Elements: - An existing contract between plaintiff and another party - D intended to procure breach of contract - D knew there was a contract - P suffered damage Unlawful Interference With Business Interests: Elements: - Interference with business interests - By unlawful means - With an intent to injure - Resulting in loss or injury Distinctions Between the Two: - Existence of a contract in one, not the other - Accessory liability versus primary liability: o Someone else does the tortious behaviour, or the D does it - Wrongfulness requirement only applies to unlawful interference. Inducing a breach need not be wrongful: can be a business conversation about a business transaction - Intent to harm is only necessary in unlawful interference. Mainstream Facts: D approached by 2 men working for Mainstream, proposing a side deal. D asks if they have a conflict of interest and they lie that they don’t. Issue: Has D committed a breach? Did he induce them to breach the contract? Held: No breach by D Analysis: No mental element: he honestly believed there was no breach. Despite his suspicion, he asked and was told it was OK. OBG Facts: OBG going into receivership which means people come in and take over running the business while it closes down. The people doing that were improperly appointed. Not knowing that, they conducted their business affairs. When it came out that they were not appointed properly, OBG complained that they injured it’s economic interest in their conduct. Held: For D Analysis: No wrongful behaviour. No harm was committed: no evidence that they could have gotten a better deal. Company was bankrupt, loss was not due to actions by receiver. No mental element: honest belief that they were rightfully appointed. Defamation Defamation is a statement injurious to a person’s reputation. - Spoken: slander. It was more common when the rules were developed; as a result slander law is more complex. - Published/broadcast: libel. Covers anything permanent or semi-permanent. Defamation arose from the ecclesiastic context, from the sin of speaking poorly of another. At first, with the evolution of the printing press, libel was brought under criminal libel charges, as part of treason and sedition laws. Early cases (1600s) were tried in the Star Chamber and defined many of today’s rules. In the 1700s the Star Chamber was abolished and it became a matter for tort law. One of few surviving strict liability torts. Only a list of specified defences can be invoked if you publish something defamatory. “Hitting someone with words”. In Canada libel carries the presumption of falsehood and the presumption of damages. Elements: - Defamatory meaning o To the plaintiff’s discredit; meaningless name-calling o Standard: what the reasonable and fair person would understand. I.e. not what the speaker intended or what the victim understood. o Read b/w lines but don’t strain to find worst possible meaning. - About the plaintiff: o Must identify P directly or by implication, or as part of a narrow group (UBC profs). Group can’t be too big however. - Publication: o Communication to a third party o More than one publisher can be liable o Problem arises with ISPs. Is Wikipedia responsible for the content on its site? Generally defamation is easy to prove. Onus on D to prove a defence. Pitfalls for Defendants - no defence of unintended meaning - negligent or fault not required - damages are presumed Possible Defences: - Truth - Fair comment - Privilege - Qualified privilege - Consent Truth - - Relatively hard to prove the statement was truth Onus is on D. Proving the facts AND proving sinister motives o Ex: in one case D could prove the facts, that the victim had left to US after tax investigation. Difficult to prove the word “fled” Substantial Truth Test: must prove the “sting” of the libel was true o Ex: CBC reported woman took children to white supremacist event in KKK uniforms o CBC couldn’t prove the uniforms but proved that she took the kids there. The sting was proven. Fair Comment - Must be comments, i.e. opinions, deductions, inferences. Not objectively provable. - Honestly believed - Matter of public interest - Based on true facts - No malice or recklessness – desire to injure; not caring if true - “Fair” is misleading: opinion can be “obstinate, prejudiced” as long as honestly held. Privilege - Lawyers in Court, MPs in Parliament (not on campaign), participants in public hearings: enjoy privilege for their words - Communications necessary in the process: witness statements given to prosecutors - Edges are “fuzzy” - Media has privilege in reporting official proceedings fairly and accurately. Allows publication of comments without charge of libel Qualified Privilege - Near privilege: reporting of court documents - Can be lost if malice or recklessness - Duty or interest in making and receiving the communication. Ex: reporting suspected grow operation to police. If it turns out to be false, law protects the communication. - In reporting libel lawsuit, media can reproduce facts including alleged libellous words – clearly indicating that the words are alleged false by P Consent - Consent is one reason reporters talk to the subject of the story. By talking to the reporter the person is deemed to consent to publication. Apologies - Apology can mitigate damages Must be genuine acknowledgement and correction of error, and expression of regret Must reach same audience as original libel. Same day and time if broadcast; same section of the newspaper. Internet - Laws haven’t changed much since 1700s and are ill-equipped to deal with changing technology. - How to apply “publisher” to ISPs? Are those publishers responsible and if so, at what point? Only upon notification and request for removal? o US and UK have found that the online publisher becomes liable at the moment of notification and must remove the libellous statement. o US immunity for ISPs by statute - Is hyper-linking to defamatory sites libel? - Online forum makes it much easier for the victim to respond. Does that make a difference in our views on libel? Forum Shopping - Due to global nature of internet, can sue or be sued in any jurisdiction. - Leads to forum shopping: finding least speech-friendly jurisdiction to file the suit. - This has led to many suits in Canada, which is plaintiff-friendly. ADD THE CASES