Unit 19

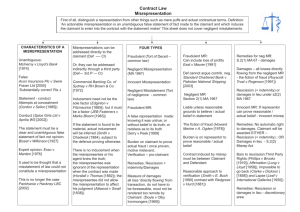

advertisement

Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities UNIT 19 - MANUAL THREE MISREPRESENTATION & MISTAKE 1 Identifying misreps 2 Statements may be representations if encourage party to enter contract but not forming part, made by A to B to induce B to enter into contract although not have to be sole reason provided did induce in some way – false statement post-contract not misrep as did not induce B to enter - & party claiming misrep occurred has burden of proving conditions/ definition satisfied but where B does not rely on A’s statement, not misrep even if incorrect; Must be of fact rather than mere opinions (Bisset v Wilkinson [1927]) although opinions may be misrep where could only be held based on factual knowledge (Smith v Land & House Property Corporation (1884)) & can be by conduct (Spice Girls v Aprilia World Service [2000]); Whilst silence itself not = misrep unless obligation to disclose facts (e.g. insurance), partial truths (Dimmock v Hallett (1866)) or, where original statement true, failure to disclose change in circumstances (With v O’Flanagan [1936]) may, but if A makes false rep discoverable by B, say, checking papers & B fails to check, remains misrep & B does not lose claim misrep (Redgrave v Hurd [1881]). Misrep remedies Contract becomes voidable (= valid until innocent party avoids it) but not bound to do so may affirm (= treat as continuing) & just seek damages but where he decides to avoid he rescinds it & rescis available, irrespective of misrep type but B must first notify A of decision within reasonable time so that A aware, although where A deliberately disappears he deprives himself of such notification right & if B shows his intention by overt & obvious acts falling short of communication, sufficient (Car & Universal Finance Co Ltd v Caldwell [1965]); Rescis restores parties to pre-contract positions so where B notifies A he intends rescis due to A’s misrep, goods restored to A & monies paid refunded to B to prevent unjust enrichment & neither required to perform any further contract obligation; Rescis equitable remedy barred where (i) innocent party not rescind within reasonable time & if excessive delay right lost (Leaf v International Galleries [1950]); (ii) contract affirmed in knowledge of facts entitling rescis (Caldwell); (iii) goods destroyed/ consumed since parties cannot be returned to pre-contract positions if goods can’t be restored but restitution not have to be exact & party can rescind if can make substantial restitution (Erlanger v New Sombrero Phosphate Co (1878)); & (iv) goods passed to 3rd parties since B has good title until A rescinds & if passed before rescis, 3rd party obtains good title; Courts may award damages in lieu of rescis where misrep was innocent or neg but not where fraudulent & is equitable remedy at court’s discretion so (i) claimant not have right to damages (S.2(2) Misrep Act 1967); (ii) in determining whether to exercise discretion courts consider importance of misrep in relation to main subject matter, resulting loss if contract upheld & Page 1 Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities loss resulting from rescis (William Sindall Plc v Cambridgeshire County Council [1994]); & (ii) where right to rescind lost/ debarred so is claim under s.2(2) (Zanzibar v British Aerospace Ltd [2000]); As well as affirming/ rescinding innocent party may also claim damages – o If fraudulent misrep, under tort of deceit so (i) claimant must show def made statement of fact knowingly or was recklessly careless as to truth, he intended claimant to act on misrep & claimant did so act & suffered damage as a result; & (ii) damages aim to place claimant in pre-tort position if misrep not been made & may be more than usual in tort as Wagon Mound reasonable remoteness foreseeability rule not apply so claimant can recover all losses directly resulting from misrep (East v Maurer [1991]); o If Neg misrep, special relationship between A & B, including reasonable reliance, creates right in Neg (Hedley Byrne & Caparo) where proof required less onerous since deceit requires proof of def’s intent/ knowledge of falseness which difficult to establish whereas Neg doesn’t require motive or intent but liab restricted by Wagon Mound reasonable foreseeability remoteness rule; But more favourable to claimants to act under S.2(1) Misrep Act – o Where misrep made by other contracting party, he is liab unless can show that, up to time contract made, had reasonable grounds to believe statement of fact was true & did so believe (but if misrep made by 3rd party, action can only be taken in deceit or under Hedley Byrne) & liab assumed unless truth test proved but difficult to establish maker’s grounds for belief reasonable & insufficient that belief honestly held – must also be reasonable (Howard Marine & Dredging v Ogden [1978]); o Damages awarded as if were fraudulent misrep (measure is of deceit rather than Neg) based on s.2(1)’s wording which compelled court to apply fraudulent misrep rules so argument that ref to fraud was fiction rejected since contrary to the plain stat words used (Royscot Trust v Maidenhead Honda Centre [1991]); o Smith New Court Securities Ltd v Scimgeour Vickers Ltd [1996], queried whether ‘loose’ wording compelled courts to treat morally innocent as if guilty of fraud & harsh to apply fraudulent misrep rules where def has reasonable founds for belief, not acting fraudulently & may have even tried to check accuracy so fairer to apply Hedley Byrne rules – with consequently lower damage award & hard to defend Royscot’s determination that def who cannot prove beliefs reasonable is treated more severely than neg. def but despite Smith New Court obiter, Royscot remains good law & reduces deceit’s importance as no point in establishing fraud since damages calculated same way under s.2(1) which does not even require Neg to be proved; o Where def establishes reasonable grounds for belief, misrep innocent & claimant has no damages rights but may be able to rescind (if no bars to this) or claim damages in lieu of rescis under s.2(2) & whilst unclear how s.2(2) damages calculated, Wm Sindall indicates should reflect loss arising from property not being what it was represented to Page 2 Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities 3 be & never > damages awardable if rep contract term & claimant suing for breach. In addition to rescis, innocent party can claim indemnity re expenses necessarily incurred from entering into contract but this very restricted in application (Whittington v Seale-Hayne [1900]) & only likely to be pursued where claimants have no rights under Hedley Byrne or s.2(1). Identifying mistakes 4 Common mistake (= where both parties are mistaken about same point) – o Where unbeknown to both parties contract subject matter ceased to exist pre-contract (Galloway v Galloway [1914], Couturier v Hastie (1856) & S.6 SOGA); o Quality (Bell v Lever Brothers Ltd [1932); Mutual mistake where both parties mistaken but not in same way – misunderstanding &/ or cross-purposes; Unilateral mistake where only one party is mistaken, other party must be aware of mistake &, whilst can concern any contract aspect usually involve mistakes as to other party’s ID as where rogues misrep ID to obtain goods without paying. Affect of mistake At common law, courts reluctant to recognise that mistakes affect contract based on undesirability of letting parties withdraw because too easy to claim buyer had second thoughts after seeing same goods etc cheaper elsewhere & unduly harsh on B if A was permitted so to do so where A & B freely entered into contract, courts hold both to obligations as uncertainty would result if A could withdraw because of his mistake but where common law recognises mistake, courts void contract ab initio (= treated as if never existed & no rights/ obligations created); Drastic effect (adding to reluctance) since courts seek to return parties to precontract position so goods/ money acquired must be returned, obligations remaining not have to be performed & original seller can recover goods sold on to 3rd parties, including purchases in good faith by innocent 3rd party, even if original seller late in making rescis, because contract void & good title never acquired; Where there is common mistake re subject matter existence contract void (Couturier & S.6 SOGA) but where, as a matter of construction, it was implied that A had actually promised B that specific goods existed, A assumed risks of non-existence so contract not void for mistake but rather A in breach (McRae v The Commonwealth Disposals Commsn [1951] (Australia)); McRae indicates only goods which at some time existed governed by s.6 & where goods never existed, courts must have regard to construction but arguable that such distinction not supportable & should be consistency of treatment irrespective of it but clarification from Associated Japanese Bank v Credit du Nord [1988] - mistake must be substantially shared by both parties & must render subject matter essentially & radically different from that parties believed to exist; Page 3 Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities Mistakes re quality will only void contracts where both parties believe quality’s existence makes item without such essentially different (Bell); In mutual mistakes where, say, A intends to sell X to B but B thinks he is buying Y, Courts decide on what reasonable person would assume to be parties’ intentions & if appears there is contract on A’s terms because B’s mistake unreasonable, B in breach if refuses to proceed or if appears A’s mistake was unreasonable, then there is contract on B’s terms & A in breach if refuses to sell Y but if situation too unclear to reach conclusion contract is void; In uni mistakes re ID, where contracts concluded distantly only confusion between distinct entities where A shows he only intended to contract with B specifically voids by mistake (Cundy v Lindsay (1878)) but where rogue merely adopts an alias & there is no other entity it is not (Kings Norton Metal Co Ltd v Eldridge, Merrett & Co Ltd [1897]); In face to face situations where A sells to B physically present at time, presumption = A intends to contract with B & contract not void for mistake unless B’s ID crucial to contract formation (Ingram v Little [1961]) but Lewis v Averay [1972] held Ingram is confined to its special facts albeit that Denning felt distinguishing between ID (which voids contract) & individual’s attributes (which does not) was fine distinction which is really no distinction at all; Where A knows B mistaken re contract term, A obliged to tell B & if knew B apprehended contract in different sense to that which A intended, A not permitted to insist B is bound – where there is mistake about contract terms, contract is void (Smith v Hughes (1871)); Equity may recognise mistakes common law does not & set aside contracts on terms since its role = mitigate rigidity of common law (Solle v Butcher [1950]) but difficult to say when & if equity will intervene & such relief not given in above mistake cases so remains very much last resort & although it provides flexibility re remedies (substitution with what court considers just & fair arrangements) it is uncertain – difficult to predict what, if any, terms will be imposed; Overall, courts must firstly decide whether contract specifies who bears risk of mistakes & only if silent must then consider whether at common law contract void for mistake – if so equity not arise but where contract common law valid, courts may consider pleas re mistakes at equity (Associated Japanese Bank Ltd v Credit du Nord SA [1989]); However, in Great Britain Peace Shipping Ltd v Tsavliris Salvage Ltd [2002] C of A overruled its decision in Solle on grounds of per incuriam – doctrine of equitable rescis in Solle irreconcilable with Lords’ decision in Bell & held no equitable jurisdiction to give rescis for common mistake in circumstances where common law found contract valid as not possible to distinguish mistakes fundamental in equity from those which at common law made contracted thing essentially different from what it was believed to be. Page 4