Explication Exercise

advertisement

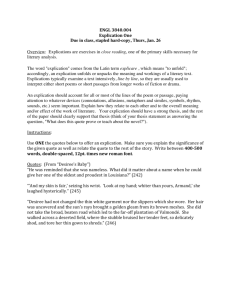

Explication Exercise In any paper that requires you to deal with an original source (a text – diary, novel, essay, letter, painting, photograph), talking about the text in general terms will weaken your argument, and hence, your interpretation. Your job as a critic is not to tell your readers what the work you've read is about, but to show them how the text works, thus improving their understanding of what it says specifically. It follows that almost any critical paper depends on explication – a word derived from Latin explicare, to unfold or to explain. An explication explains by unfolding; it goes through a given piece of text in detail, gradually revealing its meaning. Often, it relates one piece of a work to other pieces, showing the reader how the author develops themes as the book progresses. There are two ways of writing explications. One is to ladle the text into the paper in a block quote (not more than 8-9 double-indented lines; long block quotes make readers skip), then work with it for several paragraphs, unfolding its meaning and implications. The other way is to needle little pieces of the text into your own sentences, using the text to further your argument. This exercise has to do with ladling. It is designed to give you an alternative to dumping a block quotation in a paper without introduction and letting it stand on its own – a common error in student papers. In this exercise, you will be dealing with two passages out of The Decameron. You will link them with a three paragraph bridge, in such a way that your link reveals the theme the two passages have in common and shows how the second one deepens the implications of the first. What you say is up to you (there's lots to say, and many ways to say it), but the form of what you say must follow the rules below. Start by blocking the passage on page 32 of the Decameron that begins by reflecting on Ser Cepparello's wickedness, concluding that he is probably damned. "And if this is the case . . ." and go to the end of the paragraph, concluding "being most certain that we shall be heard." Then, on a different piece of paper, block the opening of the book, on page 1: "Here begins the book called . . . ." and stopping at the end of the italics. Now, start your three-paragraph bridge between the two quotations, explaining how the first relates to and deepens the meaning of the second. 1. Explicate the first passage by unfolding its meaning. The process will involve placing the quote in context, telling us that it comes at the end of the first story of the first day, that Ser Cepparello was a great sinner and a great story-teller, and whatever else you thing pertinent. (Remember, you're not just explicating; even at this stage, you're heading towards the second quotation.) 2. Extend your ideas by reflecting on the broader implications of the passage. While you will still be talking about the passage you explicated, you will also be talking about irony, double meanings, ambivalence, and other aspects of the book that the passage exemplifies. 3. Finally, write a paragraph that discusses matters implied in the first quote and its context (as you've set these up), but which can be explored completely on in the context of the second quote. By the end of this paragraph, you should have the second quote all set up and ready for further explication (which you don't have to do). The trick is to make paragraphs 2 and 3 move towards the second quotation.