Law-100-Constitutional-Young-Emily-Fall

advertisement

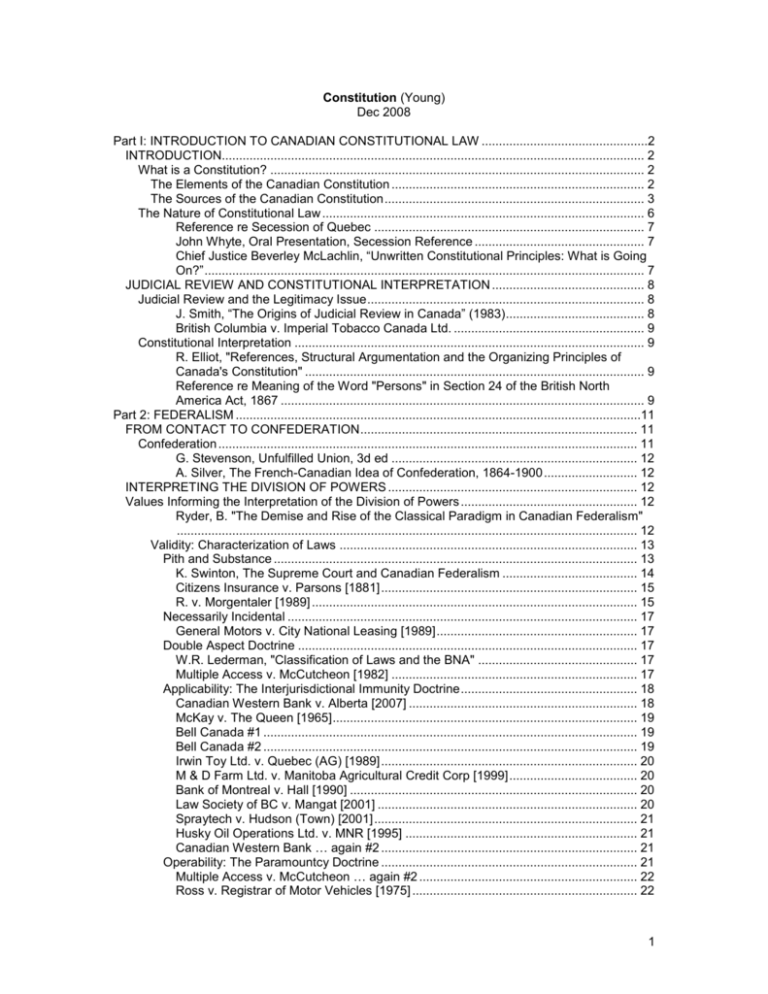

Constitution (Young) Dec 2008 Part I: INTRODUCTION TO CANADIAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW ................................................2 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 2 What is a Constitution? ............................................................................................................ 2 The Elements of the Canadian Constitution ......................................................................... 2 The Sources of the Canadian Constitution ........................................................................... 3 The Nature of Constitutional Law ............................................................................................. 6 Reference re Secession of Quebec .............................................................................. 7 John Whyte, Oral Presentation, Secession Reference ................................................. 7 Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, “Unwritten Constitutional Principles: What is Going On?” ............................................................................................................................... 7 JUDICIAL REVIEW AND CONSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATION ............................................ 8 Judicial Review and the Legitimacy Issue ................................................................................ 8 J. Smith, “The Origins of Judicial Review in Canada” (1983)........................................ 8 British Columbia v. Imperial Tobacco Canada Ltd. ....................................................... 9 Constitutional Interpretation ..................................................................................................... 9 R. Elliot, "References, Structural Argumentation and the Organizing Principles of Canada's Constitution" .................................................................................................. 9 Reference re Meaning of the Word "Persons" in Section 24 of the British North America Act, 1867 ......................................................................................................... 9 Part 2: FEDERALISM .....................................................................................................................11 FROM CONTACT TO CONFEDERATION ................................................................................ 11 Confederation ......................................................................................................................... 11 G. Stevenson, Unfulfilled Union, 3d ed ....................................................................... 12 A. Silver, The French-Canadian Idea of Confederation, 1864-1900 ........................... 12 INTERPRETING THE DIVISION OF POWERS ........................................................................ 12 Values Informing the Interpretation of the Division of Powers ................................................... 12 Ryder, B. "The Demise and Rise of the Classical Paradigm in Canadian Federalism" ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Validity: Characterization of Laws ...................................................................................... 13 Pith and Substance ......................................................................................................... 13 K. Swinton, The Supreme Court and Canadian Federalism ....................................... 14 Citizens Insurance v. Parsons [1881] .......................................................................... 15 R. v. Morgentaler [1989] .............................................................................................. 15 Necessarily Incidental ..................................................................................................... 17 General Motors v. City National Leasing [1989] .......................................................... 17 Double Aspect Doctrine .................................................................................................. 17 W.R. Lederman, "Classification of Laws and the BNA" .............................................. 17 Multiple Access v. McCutcheon [1982] ....................................................................... 17 Applicability: The Interjurisdictional Immunity Doctrine ................................................... 18 Canadian Western Bank v. Alberta [2007] .................................................................. 18 McKay v. The Queen [1965] ........................................................................................ 19 Bell Canada #1 ............................................................................................................ 19 Bell Canada #2 ............................................................................................................ 19 Irwin Toy Ltd. v. Quebec (AG) [1989] .......................................................................... 20 M & D Farm Ltd. v. Manitoba Agricultural Credit Corp [1999] ..................................... 20 Bank of Montreal v. Hall [1990] ................................................................................... 20 Law Society of BC v. Mangat [2001] ........................................................................... 20 Spraytech v. Hudson (Town) [2001] ............................................................................ 21 Husky Oil Operations Ltd. v. MNR [1995] ................................................................... 21 Canadian Western Bank … again #2 .......................................................................... 21 Operability: The Paramountcy Doctrine .......................................................................... 21 Multiple Access v. McCutcheon … again #2 ............................................................... 22 Ross v. Registrar of Motor Vehicles [1975] ................................................................. 22 1 Rothmans v. SK [2005]................................................................................................ 22 Canadian Western Bank … again #3 .......................................................................... 23 Reference re Employment Insurance .......................................................................... 23 Peace, Order, and Good Government ....................................................................................... 23 AG Canada v. AG Ontario (Labour conventions) (1937) ............................................ 24 AG Canada v. AG Ontario (The Employment and Social Insurance Act) (1937) ........ 25 Co-operative Committee on Japanese Canadians ..................................................... 25 Canada Temperance Federation (1946) AC 193 ........................................................ 26 Ref Re Anti-Inflation Case ........................................................................................... 26 K. Swinton, The Supreme Court and Canadian Federalism ....................................... 27 Part I: INTRODUCTION TO CANADIAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW INTRODUCTION What is a Constitution? Q. What is the purpose of a Constitution? Protects values, rights Outlines structure of govt Defines relationships and boundaries between govt and individuals Framework for legislation, exercises of state power Rules, principles, and practices that relate to govt and society "[Constitutional law is] the law prescribing the exercise of power by the organs of a State. It explains which organs can exercise legislative power (making new laws), executive power (implementing the laws), and judicial power (adjudicating disputes), and what the limitations on those powers are." "A constitution has been described as ‘a mirror reflecting the national soul’: it must recognize and protect the values of a nation.” from Hogg, Peter. Constitutional Law of Canada Addresses several key relationships Federal and provincial govt – each with respective sphere of jurisdiction, respective authority Individual and state – Charter, autonomy for individuals from state interference State (both levels) and Aboriginal peoples – emerging relationship that Constitution recognizes, establishes, and protects (s. 35); how relates to both levels of govt and issues of self-government The Elements of the Canadian Constitution Parliamentary Democracy: laws made by elected legislature legislature has extensive authority Federalism: division of govt along territorial lines fed govt: power to enact laws of national concern prov govt: power to enact laws in relation to matters of local concern Individual & Group Rights: rights: claims individuals & communities have against the state Entrenched Aboriginal Rights: rights recognized by the Constitution as belonging to the Aboriginal peoples in light of the fact that lived here first 2 Legislative Supremacy: in Britain, parliament could enact any legislation & couldn’t be changed colonial legislative supremacy was tempered by imperial power since the birth of Canada: tempered by the principle of federalism which enure Parl & Prov legislatures were supreme only when they were exercising powers conferred on them by the Constitution also significantly modified by enactment of CCRF passed down to Can from Constitution The Sources of the Canadian Constitution Knowing about sources of Constitution allows understanding of hierarchy ENTRENCHED – protected from ordinary legislative amendment; gives stability and predictability Need balance between flexibility and stability Flexibility often introduced through JUDICIAL INTERPRETATION Written documents – come in two types: Imperial Statutes (and Orders in Council) – enacted by UK's Parliament in Westminster, acting in role as Imperial Parliament – laws affecting all colonies 19 Imperial Statutes – two key ones o Constitution Act, 1867 (formerly: British North America Act, 1867) – confederating document o Canada Act, 1982 – includes Constitution Act, 1982, which is Schedule B and has Charter as Part I o 4 Orders in Council Canadian Statutes o 8 Canadian Statutes – enacted by Parliament in Ottawa, have been entrenched Case or Common Law Courts have task of interpreting text of Constitution, their decisions become precedents Prerogative and Privilege Certain residual, inherent privileges granted by common law, can be revoked by statutes Crown Prerogatives – e.g. Honors like Q.C., Order of Canada, issuance of passports, pardons Parliamentary Privileges Conventions Repeated patterns of behaviour, functions of govt Not legally enforceable, but politically powerful (sanction, pressure) e.g. When calling election, PM requests permission from Gov General to dissolve Parliament, GG usually says yes … King Bing scandal e.g. Federal Disallowance – federal govt can disallow provincial legislation according to Constitution Act, but never incited as justification e.g. major public change requires referendum e.g. Notwithstanding Clause – can pass law that breaches s.15 Unwritten Principles Understood by courts to be foundational, but not written anywhere Legally enforceable e.g. principle of democracy 3 DOCTRINE OF RECEPTION – when colony established, received all statutes and common law decisions of UK at date of settlement UK laws established after that date did not apply, except Imperial Statutes Body of law could be amended, changed, etc. by colony Q. How did Canada go from body of laws granted in doctrine of reception to modern day? English common law of colonization: doctrine of reception… colony acquired by settlement, settlers brought with them English law which then became the initial law of the colony colony acquired by conquest, law of the conquered people continued in force, except to extent necessary to enable gov’t institutions of British colonial rule colonial legislature could adopt laws of England as of a certain date English laws imposed by imperial power as of a certain date. This is what happened in Quebec by means of the Royal Proclamation of 1763; pre-conquest French civil law was restored by Quebec Act (an imperial statute) in 1774 First two rules of reception—regarding settlement and conquest, not particularly wellapplied…often applied in disregard of the existence of aboriginal peoples… All laws in force in England up to but not after the date of reception became part of the laws of the colony. Colonies received the entire body of English law—statute and common law Once reception occurred, colonial government was not stuck with a rigid set of laws. The government was able to enact its own amendments or repeal of statutes “received” from the United Kingdom. It could also pass new laws of its own making. And, importantly, what ever the British Parliament (not the Imperial Parliament) did, after the date of reception, did not apply in the colony. British Parliament and Imperial Parliament—both Westminster Parliament (acting in different capacities). Westminster Parliament, when making laws for the overseas territories of the British Empire, binding on colonies and unamendable by their colonial governments, not by virtue of reception was known as the Imperial Parliament and its enactments were known as imperial statutes. Such imperial statutes were of English laws nor by the adoption of the colonial legislature, but by the imperial statute’s own force as an expression of colonial power (doctrine of repugnancy). Judges in charge of "policing" colonial power. Q. What about common law? Could a Canadian judge dispense with British precedents? Because of tradition of common law, British case law still relevant even though date of reception has technically passed. Only one-way transfer of power – Canada case law not binding on Britain. These cases are PERSUASIVE, but NOT BINDING. Statutes can be passed to codify or override common law precedents. Canada Act, 1982 last imperial statute, will probably last in perpetuity … So, potentially there are three classes of statutes in force in any colony: domestic statutes of the United Kingdom in force in England at colony’s reception date (subject to amendment by colonial legislature); imperial statutes in force at date enacted, independent of reception date (not subject to amendment by colonial legislature); statutes passed by the colony’s own legislative assembly. 4 doctrine of suitability --those British statutes that were clearly unsuitable for application in the colonies were not in force in the colonies… left to the colonial courts to determine which statutes were to be deemed unsuitable… [See handout – "Canada's Path to National Independence" & annotations] 5 p. 60 – Constitution Act, 1982 Part VII, s. 52 – "supremacy clause" These are terms of doctrine of repugnancy, but has become domestic Legitimacy of courts comes out of this; long history of judicial review The Nature of Constitutional Law Pre-History to the Secession Reference 1980 referendum under Levesque – 59% rejected Promise of renewed federalism Renewal of Constitutional negotiations Patriation Reference – Asking SCC whether it was constitutionally sound for federal govt to send Constitutional amendments to be passed by Westminster without consent of provinces SCC judgment: Not conventionally proper Trudeau and premiers reconvened to discuss amendments Fall 1981 discussion – "five days of madness" Result: deal signed between 9 provinces and federal govt … nobody consulted Levesque! Left out: s. 35 aboriginal rights, s. 28 guarantee of equal rights for men and women – these groups rallied, rights put back in Resolutions passed the House and was taken to Westminster April 1982 Royal Proclamation – Queen signs new Constitution into legal force Example of ROYAL PREPROGATIVE – little bit of power left over Following this, failed attempts to bring Quebec's interests into constitution 1987 Meech Lake 1992 Charlottetown Accord 1995 referendum on sovereignty – Q. Should Quebec be made sovereign? Assumption that would not need to follow amending formulae (s.5) from 1982 If successful, QC could unilaterally declare independence and secede legally 50.6% against … referendum defeated by 1.2% Questions brought before SCC – 3 questions in Secession Reference Almost endless demand for limited judicial resources … how does SCC determine which cases they will hear? Rules of STANDING – to determine who can bring an issue before SCC o Criteria: public interest, referred by lower court o Another way: REFERENCE PROCEDURE – relies on statutory authority Federal level – see: Supreme Court Act R.S., 1095 S-26 Referred by Governor in Council (Cabinet/Executive) Each province also has legislation for references See: Constitutional Question Act RSBC 1996 Chapter 68 Referred by Lieutenant Governor in Council QC refused to attend proceedings – claimed SCC had no legitimacy b/c judges not an independent arbitrer … appointed by PM! o QC premier Lucien Bouchard claims only tribunal is Quebec people Court appoints amicus curae, intervenors appeared 6 Reference re Secession of Quebec Huge political consequences for Canada and political principles JJ discuss issue of JUSTICIABILITY Inclusion of history – for context, unwritten principles of Constitution Unwritten principles are completely necessary and are essential for Constitutional development, interpretation Text has primacy, but principles have legal force. Can overrule govt actions, unlike conventions Unilateral secession is unconstitutional. Federalists: secession must follow rule of law, be constitutional Sovereigntists: vote of people, statement that "yes" vote would impose a duty/reciprocal obligations on rest of Canada to negotiate constitutional changes – "duty to negotiate" Entire judgment doesn't refer to any single part of Constitution In many ways, SCC decision was unsatisfactory: What negotiation details follow? What amending formula? What constitutes a "clear question"? What would the content of negotiations be? What can be negotiated? What parties would be involved? (Federal govt/QC … All provinces/QC) What if there is an impasse and no settlement can be reached? Courts rejects principle of radical sovereignty, yet also rejects position of radical federalism Result: both QC and federal govt claimed victory Bouchard: "Court affirmed … process that would legitimately be set in motion by a Quebec referendum on sovereignty" Chrétien: "The unilateral declaration of independence … is contrary to Canadian law and to the fundamental principles of democracy" … "secession is as much a legal act as a political act" and secession required more than simple majority. No ambiguity, complexity and difficulty of negotiations suggests that "everything would be on the table" Accusation that SCC should have never heard the case in the first place Federal govt used SCC for political, abstract purpose; b/c appointed, allied with fed govt Manipulated judicial system to achieve aim that federal govt could not Puts SCC in a space b/t constitutional law and constitutional politics Counter-argument: SCC has to answer reference questions Federal govt passed Clarity Act, June 2000 Within 30 days of referendum question, House of Commons has to determine whether question is clear If not clear, federal govt will not engage in negotiations If it is clear, whether there is a clear majority casting a vote in referendum Any proposal for secession must consider questions: debt, territorial, minority and first nations rights, etc. John Whyte, Oral Presentation, Secession Reference Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, “Unwritten Constitutional Principles: What is Going On?” 7 JUDICIAL REVIEW AND CONSTITUTIONAL INTERPRETATION Judicial review describes specific judicial function In Constitutional Law, this means the power of courts to determine, when they are properly asked to do so, whether a govt body/actor/act is in accordance with Constitution Furthermore, power of courts to declare govt body/actor/act is unconstitutional – of no legal force or effect Courts can only pronounce when asked to do so; cannot take independent action o Can make speeches and express concerns, but cannot directly and explicitly incite the public to act, for example o Idea that there is a separation between law and politics Complicated notion … is there actually a distinction between 2? Is it possible that law can be apolitical? Q. What makes judicial review legitimate? (Think about how much power JJ have!) Concerns about JJ power o Undemocratic – JJ are not elected, they are appointed by politicians o Unaccountable – serve to age 75, no responsibility to electorate o Elite group in society given background, education, employment, etc. o Unrepresentative – class, race, citizenship status, sexuality, gender, age, not member of aboriginal group o Perhaps out of touch with popular sentiments On the flipside o J are not accountable – have no political masters, do not need to curry favour of electorate for re-election o Independent, removed and detached from politics … JJ not supposed to do what politicians do o Experts in law as a result of education o Being out of touch with popular sentiments might better represent minority concerns JJ overturn democratic actions, yet can be seen as strengthening democracy Can check unbridled democratic, political processes but with same values of democracy Judicial review under federalism, division of powers When SCC declares legislation is ULTRA VIRES of one level of govt, that means it is outside jurisdiction of that level … but that law can still be passed by other jurisdiction Still allows legislation to be passed Judicial review under Charter If legislation is contrary to Charter, cannot be passed by any level of govt Judicial Review and the Legitimacy Issue J. Smith, “The Origins of Judicial Review in Canada” (1983) Some of historical debates over legitimacy of judicial review, competing visions of federalism Refers to LEGISLATIVE UNION, same as idea of UNITARY STATE Opposite of FEDERAL STATE Single central legislature with full range of legislative powers Judicial committee of Privy Council Historically, final appellate authority for British empire 8 Traditionally an advisory body, but judgments actually treated as binding s.101 of BNA Act allowed Canada to set up SCC. Canada established SCC in 1875, but appeals to Privy Council allowed until 1949 (last appeal heard in 1959) p.116 FEDERAL DISALLOWANCE POWER – s. 55-57, s.90 of Constitution Act, 1982 Power for federal govt to veto any provincial enactment Remains in Constitution Act and has been used in the past Would not be used now b/c convention is that that provision is unusable Federal disallowance power would favour federal govt, SCC would allow a balance Yet concern that SCC would disrupt federalism b/c always avenue for recourse Yet another concern that SCC would favour federal govt, give its enactments legitimacy British Columbia v. Imperial Tobacco Canada Ltd. BC govt wanted to sue tobacco company for impact on health care system costs, saying that manufacturers had duty of care towards customers Tobacco companies challenged this: outside jurisdiction of provincial govt (in legal and territorial sense); cast of law contrary to unwritten constitutional principles e.g. rule of law Act was retroactive; past responsibilities imposed on tobacco companies Act singled out tobacco companies Favoured provincial govt Appellate court dismissed appeal and upheld law, stated that rule of law doesn't speak to tobacco company's concerns Rule of law has three elements: o p. 57 Laws supreme over everyone o Requires creation and maintenance of an order of positive laws o Relationship b/t state and individual must be structured by laws o Ultimate goal of rule of law: protection against arbitrary exercise of power by those with power against those without; protection against favouritism or targeting o o o Court rejects idea of expanding rule of law Render many Constitutional rights useless Would be giving pre-eminence to rule of law over Constitution Constitutional Interpretation R. Elliot, "References, Structural Argumentation and the Organizing Principles of Canada's Constitution" Reference re Meaning of the Word "Persons" in Section 24 of the British North America Act, 1867 During time of changing forms of formal equality for women; ongoing barriers of race, class 1929 – women barred from Senate (family law matters, approved divorces until 1970s) Case spearheaded by 5 powerful women sending citizen's reference to SCC by petition 3 members of provincial legislatures, 1 magistrate, 1 political activist Originally a request to amend Constitution – failed Challenge specific to s.24 – women considered "persons" elsewhere s.23 had other criteria – 30 years old, citizenship, property owners Persons Day, Oct. 17 celebrates Judicial Committee of Privy Council's decision 9 SCC decision does not engage in question of whether it is desirable or not that women are appointed to Senate – that would be a matter of politics, not law Anglin's focus: (Historical argument/original or framer's intent rule. Common in US Constitutional cases) Term "persons" in 1867/1929 If it meant men in 1867, would mean men in 1929 Is this legitimate? original rafters were men Senate is a new body with no common law or outside interpretive aids Looked at common law and ordinary meanings Lord Brougham's Act (Doctrinal analysis) – Constitution treated as ordinary document with ordinary construction (Contextual) – custom, usage, precedent (Prudential) – "good sense" – reread – vast change on "mere verbal possibilities". Stress on continuity, tradition over evolution and adaptation Why do we read this case? Clash between SCC and Privy Council SCC – narrow, strict interpretation Different styles of argumentation? What are values of historical argument? Does it bolster legitimacy of SCCC? Gives stability, predictability Societal change – form is politics, not courts ("just modify Constitution … no!") Keep law and politics separate Original intent – democratic will of people Privy Council decision Power of courts to effectively (not formally) amend Constitution Extraneous evidence – different consideration b/c no express exclusion True, common law and customs had no merit for women, but appeal to history is not effective. Times have changed, Roman laws and English cases are not good foundations for the Canadian context No presumptive exclusion of women Internal evidence – BNA Act Turns to LIVING TREE DOCTRINE (DOCTRINE OF PROGRESSIVE INTERPRETATION) – capable of growth and expansion within its natural limits Constitution must change with times, develop with new conventions, grow and evolve Not narrow and technical construction but a large and liberal interpretation that is appropriate given the status of the Constitution Judicial Committee of Privy Council says Charlton v. Lingis is distinguishable case Textual argument: If "persons" limited to men, would've been explicitly laid out (see s. 23) "Persons" is ambiguous, look at other areas in which refers to both men and women "Male persons" also an available term Decides that "persons" refers to Persons case a good illustration of living tree doctrine SCC did not move away from strict, narrow interpretations until 1970s Another example of progressive interpretation: QC reference on EI and maternity leave benefits 10 But isn't Constitutional change best dealt with through amendments? Some criticisms of progressive interpretation: Amending formulae is democratic compared to judicial decisions On the other hand, Constitution is a vague and broad document Goes back to discussion of legitimacy and concerns of judicial review Imagine what would've happened if SCC could not have been appealed to Privy Council Most likely, would've been brought before SCC again or an eventual Constitutional amendment DIALOGUE THEORY – courts and legislatures are in dialogue, and courts don't actually have the last word (can be overruled by legislation, parts of Constitution) s.33 override s.1 – justify infringement of rights On the other hand, there are still limitations that the courts place on legislatures Part 2: FEDERALISM FROM CONTACT TO CONFEDERATION History, Memory, Mythology, and Constitutional Law o J.-F. Gaudreault-DesBiens, "The Quebec Secession Reference and the Judicial Arbitration of Conflicting Narratives about Law, Democracy, and Identity Pre-Contact, Contact, and the Myth of Terra Nullius o Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Final Report, vol. 1 P. Macklem, Indigenous Difference and the Constitution of Canada New France: Canada's First European Constitutional Regime o Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Partners in Confederation: Aboriginal Peoples, Self-Government, and the Constitution From Acadia to Nova Scotia: The Genesis of the Maritimes The Expansion and Consolidation of British North America: From the Conquest of New France to the Constitutional Act, 1791 o Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, Self-government, and the Constitution Confederation Clash of narratives in Canadian history; divergent collective memories Difference between "history" and "memory" e.g. QC's memories of drafting of Constitution Act What are the dominant mainstream narratives? What are the minority, marginalized narratives? Some key points in readings: Royal Commission – complexity of Aboriginal cultures M - legal and practical responses to aboriginal presence French-English history including expulsion of Acadians Importance of Royal Proclamation of 1763 – status of QC, aboriginal peoples Quebec Act of 1773 – restoration of civil law in QC Growth and establishment of responsible govt (p.76) – foundational pillars: Executive is responsible to elected assembly (Legislative branch) and comes out of it 11 In relation to current election: if Harper wins minority govt and has vote of nonconfidence, NDP and Liberals can form coalition govt and request GG to appoint new PM without calling another election (see King-Bing Crisis) John A. MacDonald favored legislative union (central govt) – didn't want strong regional forces like US, American Civil War. Not same blocs of interests e.g. agrarian, plantation Centralist concept of federalism for stability of union Specifically defined powers to provinces and unspecified, residual powers to federal govt Prov. – less important matters e.g. social matters Fed. – more important matters e.g. taxation Of course, this has changed; nowadays, prov govt has a lot of power Establishment of QC – autonomy one of attractions of Confederation Constitution similar in principle to GB – protections, levels of govt, Crown as formal head Terms of Confederation show division of legislative powers G. Stevenson, Unfulfilled Union, 3d ed Internal difficulties within provinces of Canada Emergence of US as external threat Economic motives, competition b/t QC and ON (p.79) Termination of trade agreements b/t US and GB – move from N/S trade to E/S trade A. Silver, The French-Canadian Idea of Confederation, 1864-1900 Geographic and ethnic identities are distinct; best protected through autonomous jurisdiction – virtual independence Coordinate sovereignty – 2 nations within Canadian federalism INTERPRETING THE DIVISION OF POWERS Values Informing the Interpretation of the Division of Powers Ryder, B. "The Demise and Rise of the Classical Paradigm in Canadian Federalism" Two diff judicial approaches to defining "exclusivity" of fed and prov powers, of preserving provincial autonomy: 1. CLASSICAL PARADIGM Pre-WWII Privy Council Strong exclusivity No overlap or interplay; heads of power should be "mutually modified" to avoid overlapping "Watertight compartments" where spillover not tolerated law will be ultra vires or "read down" Weakness: social problems do not fit neatly into jurisdictional boxes, can create legislative vacuum Judicial activism Deregulation of markets 2. MODERN PARADIGM Post-WWII SCC Prohibits each level of govt from enacting laws whose dominant characteristic is the regulation of a subject matter within the other level of govt's jurisdiction Spillover will be upheld if law is in pith and substance of enacting legislature's jurisdiction Dickson CJ "fair amount of interplay and indeed overlap" 12 Weakness: compromises provincial autonomy b/c when spillover results, rule of federal paramountcy can be applied Judicial restraint Greater market regulation, issues of moral and social order Jean Beetz: classical paradigm is best means of preserving an authentic federalism w/ equally autonomous prov and fed govt Peter Hogg: judicial restraint in modern paradigm is appropriate for unaccountable judiciary Framework to understand pattern – two contrasting attitudes towards division of power Not every case fits into one or another, not chronological but trend that 2 has replaced 1 Identifies two important principles: responsible government and federal state Division of power is exhaustive, no legislation that is "outside" both levels of govt o JJ careful not to compromise this principle o But JJ have to determine balance between two levels o Paradigms define different judicial approaches to defining authorities of each level Missing piece of Ryder's analysis: how to fit indigenous presence into this? Quick review: DIVISION OF POWERS b/t federal and govt – division of legislative authority between different levels of govt in federal state SEPARATION OF POWERS b/t federal and govt – system of checks and balances on power of three branches: legislative, executive, judicial o Different visions of legislative authority; courts as final arbiters, moods about how they understand in s.91 and s.92 Court's interpretation doctrines (Overview) Arguments used to challenge statutes on ground of division of powers: 1. VALIDITY – determining whether dominant characteristic ("pith and substance") of a statute falls within a class of subjects outside the enacting govt's jurisdiction. Possible for fed or prov statutes 2. APPLICABILITY – if the legislation is valid in most applications, determining whether it should be interpreted to not apply to the matter outside the jurisdiction of the enacting body "Reading down" INTERJURISDICTIONAL INMUNITY – limits application of prov statutes to protect exclusivity of federal heads of power Lack of reciprocity – fed statutes rarely limited to protect prov heads of power 3. OPERABILITY FEDERAL PARAMOUNTCY – when two equally valid laws are inconsistent, the provincial is rendered inoperative to the extent of the inconsistency Consequences of successful challenge under each of above is different Validity: Characterization of Laws Pith and Substance Definition: dominant or most important characteristic of a challenged law Whatever is not a dominant characteristic is an incidental one 13 Double Aspect – laws determined to have both federal and provincial matters Ct have not explained when to use this compared to when it is necessary to make a choice Lederman: "when the contrast b/t the relative importance of the 2 features is not so sharp" If roughly equal – judicial restraint let either level of govt enact it: see Multiple Access Colorability Doctrine – formal trappings of matter within jurisdiction, but in reality, addressed to matter outside jurisdiction: Morgentaler Based on maxim that legislative body cannot do indirectly what it cannot do directly These arguments are rarely successful; paucity of jurisprudence Presumption of Constitutionality – burden on challenger to demonstrate K. Swinton, The Supreme Court and Canadian Federalism s. 91 federal classes (30) s. 92 prov classes (15) Debate over "peace, order and good government" (p.o.g.g.) power in opening of s.91 o Federal govt has general power, unlimited except for provincial powers? o Federal govt has residuary power to deal with matters not expressly assigned? o Federal govt has express grants of power? Choosing between competing classification – Abel: Identify "matter" of statute Delineate into scope of competing classes Determine which class challenged statute falls into Consider: statutory context, purpose, effects, function, preamble, application DOUBLE ASPECT DOCTRINE – (compared to "watertight compartments") Concerns: federalism, beliefs Process of classification of a statute to determine whether it fits under s. 91 or s. 92 o Can be tricky … numerous heads of power, but not exhaustive b/c drawn up in 1987 and lots of modern ssues that were not contemplated by drafters o Not clear where some things fall; competing classifications 3 stages (Abel): 1) Identification of matter of statute 2) Delineation of scope of competing classifications 3) Determination of class into which contested statute falls o These are useful in analytical sense, but Ct tend to collapse these o Lots of room for non-logical factors that JJ might apply Courts informed by PRESUMPTION OF CONSTITUTIONALITY 1) If court is presented with 2 equally plausible classifications, will choose the one that is constitutional (the level that has jurisdiction to enact it) o Considerations of efficiency and judicial restraint 2) If there is a finding of fact necessary to hold a piece of legislation constitutionally valid, Ct will accept that finding if there is a rational basis o e.g. Peace Order and Good Government (POGG) 3) If broad interpretation (unconstitutional) and narrow interpretation (constitutional) possible, Ct will read down Generally, if statute is invalid, it will fail as a whole, but it possible to sever 14 o Inappropriate when good is inextricably bound up with bad such that the invalid part cannot survive independently This is a starting position, that courts will exercise judicial restraint and not deal with legislative matters in finding that legislation is constitutional Going over three stages in more detail: 1) What is the matter of the statute? Finding pith and substance, dominant characteristic See Lederman article p.221 Looks at statutory content, legislative history, govt reports on problem that triggered legislation, practical/legal effects, intent laid out in preamble, debates and Hansard, speeches, govt policy paper Not determinative process, but certainly influential Ct mention they are not casting judgment on desirability After this, Ct turns mind to second stage (in reality: first and second stages intertwined, third stage arises after that) 2) Where does something with that pith and substance fall in the lists of ss. 91 and 92 PRINCIPLE OF EXCLUSIVITY – if it falls onto one list, not the other 3) Which head of power contains dominant characteristic of legislation? As Swinton points out, boundaries are sometimes blurred Citizens Insurance v. Parsons [1881] Stipulates that insurance contracts in province have to contain certain conditions unless explicitly stated otherwise (a form of consumer protection) Parson goes to collect, but denied b/c didn't comply with conditions. He argues that conditions were different from standard form and not clearly indicated Insurance company argues that provincial statute is unconstitutional Parson wins case – gives overview of classification process of pith and substance, as well as trade and commerce power, civil rights Ct. looks at 2 lists of heads of power Insurance company says they fall in federal govt's trade and commerce power so regulation has to be done by federal govt Parsons – s.92(16) "local and private matters" Step 1 – JJ's pith and substance argument: insurance legislation wholly within jurisdiction of ON; contract situated in ON, ignores national dimension of insurance company Step 2 – JJ look at scope in ss.92(13), 91, gives broad reading of civil rights to include contracts, gives narrow reading of trade & commerce. Uses technique of mutual modification. Consequently, insurance legislation is provincial jurisdiction and enacted by provincial legislation Parsons can recover This case is example of classical paradigm – use of device of mutual modification But at the same time, Ct intervening in market regulation by reading down legislation R. v. Morgentaler [1989] Medical Services Act, NS Abortions available in hospital but prohibited in clinics – govt regulation of its accessibility Morgentaler openly expressed desire to open clinic to perform abortions 15 Morgentaler challenged charges under act on basis they were unconstitutional (gained standing before SCC) Ct found legislation was unconstitutional by rejecting what legislation says its primary purpose is. Criminal law – federal govt's jurisdiction Legislation was ultra vires. s. 2 not purpose, purpose the drafters had was different Good example of pith and substance argument and of colourability Decision hinged on classification process – JJ do not explicitly follow steps of Swinton's classification but do so analytically (#1, 2 of judgment) Dominant characteristic of legislation by looking at practical effects (real world) and legal effects (preamble, provisions, stated intention) Use of extrinsic materials much more common nowadays e.g. legislative debates and speeches, reports o Extrinsic materials used in this case b/c potential for COLOURABILITY (when true purpose of legislation is masked) o That is, legislation has one purpose on its face (which is constitutional), but upon closer examination, it might have another purpose (which might be outside jurisdiction) o Ct avoided making judgment on NS govt o Ct says act so blatantly out of province's jurisdiction that can't even be colourability Next step in Swinton's classification is #3 of judgment Goal of legislation: restriction of abortion as socially undesirable practice Rejects NS's argument that this within provincial jurisdiction and no evidence of practical effect of reducing # of abortions Ct says practical effect (or lack thereof) not an important consideration p.220 suspicious timing NS's argument: concerns about safety, privitization, cost & quality problems Ct says these concerns not valid, not brought up until second reading, no studies Ct also questioned very high fines and sanctions Ct put together all of these observations Currently, access to abortions still difficult. Some hospitals have stringent policies and do not perform them; women may have to travel to other provinces Late term abortions difficult/impossible to get b/c medical professionals' views Some contexts, performed in punitive ways e.g. without anaesthetic Even though abortions not regulated by law, professional practices and social norms still in place Morgentaler example of modern paradigm, though that might not be apparent at first o Tolerance for porous, permissive boundaries between s.91 and 92 o Strikes down provincial legislation Pith and substance doctrine allows laws that are classified in relation to a matter that comes within the competence of an enacting body o Tolerance for INCIDENTAL EFFECTS as long as dominant characteristic is in enacting govt's jurisdiction o Recognizes law can have several effects but one will have to be found to be dominant o Examples: ON passes law regulating public solicitation. Intention: reduce public nuisance. Unintended effect on prostitution. Law can be intra vires provincial government. o Federal govt passes law in re to navigation and shipping, but also regulates labour relations (federal). 16 Necessarily Incidental Legislation may have impact on matters outside the enacting legislation's jurisdiction so long as effects are secondary/incidental Ancillary (Necessarily Incidental) doctrine – look at provision by itself, in the entire legislative scheme, and determine how well it is integrated General Motors v. City National Leasing [1989] s.31(1) tort for alleged infraction of act (hurt by monopolistic behavior) Tort within provincial jurisdiction over property and civil rights Why civil action? Harnesses private interest to add to enforcement; all companies watchdogs Dickson, J finds Act falls under Trade and Commerce General Regulations branch and that 3(1) can be found valid by virtue of the fact it is not overly intrusive on provincial legislation and still part of overall Act that falls under Trade and Commerce Dickson is centralist, crafts criteria to determine whether under Trade and Commerce Uses a three-part process to deal with s. 31.1 alone (NECESSARILY INCIDENTAL DOCTRINE = ANCILLARY DOCTRINE) – uses "test of fit": o Look at challenged provision alone and ask whether it entrenches on other level of govt's jurisdiction. If so, how much? How to determine if it intrudes? Pith and substance o Look at rest of statute to determine if valid/not o Look at fit between provision and whole (if marginal encroachment – loose test; if great encroachment – stricter test) As it applies to this case, Dickson says provision intrudes but not very intrusive; it's a remedial and procedural mechanism Case is example of judicial restraint Double Aspect Doctrine W.R. Lederman, "Classification of Laws and the BNA" Enumerated "subjects" or "matters" are classes of laws, not of facts Each law has multiple features – e.g. will made by unmarried person becomes void upon marriage marriage (s.91) or property and civil rights (s.92)? Inherent overlap, impossibility of mutual exclusion (subscribes to modern paradigm) Because of this, recognize that no logical way to distinguish what is federal or provincial jurisdiction; necessity of judicial decision to determine which jurisdiction it falls within o Consider stare decisis, history, vision of Canada o Consider Siméon's values: federalism, democracy, functional effectiveness, community Ct consider: language, object/purpose, intention, effects/consequences = FULL/TOTAL MEANING COLOURABLE LAW – means something more than/diff from what its word seem tat first glance to say ** Classified by feature judged to be most important Q. Is it better that it be done on national or prov level? Q. What is truly of national or provincial concern? Multiple Access v. McCutcheon [1982] Employees charged with insider trading under provincial legislation Each level of govt has legislation to regulate this kind of behavior 17 Employees claimed legislation regulating insider trading is outside jurisdiction of province of ON, doctrine of paramountcy trumps provincial legislation. Can only be charged under federal legislation, but time frame has lapsed and employees can escape liability Consider validity of legislation Judgment written by Dickson, J: Legislation started as federal legislation "Field" – area of real-life activity being regulated. In this case: insider trading Federal aspect: regulation of corporate relationships Provincial aspect: regulation of securities Ct reluctant to find double-aspect areas. A few from past: temperance, insolvency, highways, religious observance. When overlap is so extensive that it can't just be considered incidental effect, has to be double-aspect. Rejects argument for interjurisdictional immunity – Ct won't allow provincial legislation to spill into federal area Applicability: The Interjurisdictional Immunity Doctrine Use IJI when legisl is valid in most applications but should be interpreted to not apply to matter outside jurisdiction of enacting body Historically, has only been applied to some areas/heads of power Controversial doctrine – federal govt can deal with overlaps by passing its own version of legislation and using doctrine of paramountcy Canadian Western Bank v. Alberta [2007] Whether provincial consumer protection (sale of insurance) can be constitutionally applied to chartered banks (federal jurisdiction, under Federal Bank Act) Judgment written by Binnie and Lebel JJ: Federalism as a fundamental guiding principles Reference to living tree doctrine Ct as final arbiter in division of power – allow appropriate balance to be struck b/t inevitable overlaps, recognize need for national unity, reconciling two jurisdiction is responsibility of govt Begin with pith and substance doctrine as first stage in analysis More expansive embrace of external documents Merely incidental effects "do not disturb constitutionality" of enacting legislation DOUBLE-ASPECT – unable to be captured by single head of power … conclusion reached after pith and substance analysis In some cases, overlap not acceptable – interjurisdictional immunity and paramountcy Dealing with overlap o INCIDENTAL EFFECT: ignore o ANCILLARY DOCTRINE: if one overlapping feature is too broad to be dismissed, use ancillary doctrine o DOUBLE ASPECT: can be characterised as within both federal and provincial jurisdiction; can also be called "double matter"; characteristic of modern paradigm Determine: Validity Interjurisdictional immunity Applicability DOCTRINE OF APPLICABILITY – interjurisdictional immunity test; consequence has to do with application Interjurisdictional immunity Allows Ct to respond when one jurisdiction's law interferes with another; more consistent with "classic approach" to jurisdiction 18 Involves "reading down" legislation to reduce its scope In past, only federal legislation could be immunized from provincial legislation. Recently, Ct have said should be useful to both (Not only instance of Ct reading down legislation: if narrow and broad interpretations possible, and narrow preserves Constitutionality, Ct will choose it) No possibility of double aspect – if only provincial law available, can still be read down History of IJI FIC – test: otherwise valid prov law may not impair the status or essential powers of a FIC FRU – test: valid provincial law cannot sterilize or impair a FRU McKay v. The Queen [1965] Generally worded bylaw that prohibits signs McKay convicted, challenge that bylaw doesn't apply to federal election signs Ct recognizes political rights by saying their expression can only be limited by federal govt (remember this case was before Charter) Treated as good example of Ct firming up idea of interjurisdictional immunity Words given meaning in context of legislation The one which gives it Constitutional meaning should be followed imagined pith and substance of hypothetical municipal bylaw prohibiting the posting of federal election signs … this would obviously be unconstitutional Ct finds legislation can't do indirectly what they want to do directly, read down legislation Ct divided Dissent said no conflict b/c federal law had not legislated yet, we should tolerate incidental effects Set stage for reading down individual effects in otherwise valid piece of provincial legislation Bell Canada #1 Is a federally regulated undertaking More explicit about IJI than McKay Deals with QC minimum wage; no legislation at federal level until 1985 Q. is it acceptable for provincial legislation to affect federally regulated undertaking Ct said applicable unless federal govt enacted legislation in same area Will read down QC minimum wage act; that portion of employment standards legislation will be rendered inapplicable to Bell Canada Ct moves away from strict test to a more expansive one: from "sterilizing/impairing" to "affecting a vital part" Bell Canada #2 Gives IJI firm footing, confirms Bell Canada #1 Wanted to escape provincial employment regulation stating need for reassignment for pregnant employees who worked with video monitors Set out general rule - 3 provisions set out relevant federal and provincial jurisdictions o If FRU, read down o IJI applies to other areas in federal jurisdiction Apply double-aspect doctrine carefully – recognize still two jurisdictions Effect of s. 91(1) and 92(10) – create exclusive federal jurisdiction over FRU; unassailable core in that jurisdiction o In Bell #1, employment within that core Not enough to give full and adequate scope to federal govt, to use paramountcy uncertainty, inefficiency, inefficacy, over-regulation 19 Separates FRU and FIC – not same test o Bell #1 gives FRU broader possibility o Bell #2 says FRIs still use sterilizing/impairing test Beetz rejected that there could be a concurrent prov jurisdiction over a vital part of FRU "A basic, minimum and unassailable content" had to be assigned to teach head of fed legisl power and since fed legisl power is exclusive, prov could not affect that "unassailable core" Irwin Toy Ltd. v. Quebec (AG) [1989] QC consumer protection legislation that prohibited advertising to young children Irwin Toy said legislation limits broadcasters and should be read down b/c broadcasters are FRU and core of such undertakings is protected by IJI Ct say Bell Canada test can only be applied when law is applied directly to FRU. If law applied indirectly to FRU (broadcasters), must use impairment/sterilization test Irwin Toy unsuccessful "Express conflict" or "impossibility of dual compliance" "Covering the field" or "negative implication" doctrine M & D Farm Ltd. v. Manitoba Agricultural Credit Corp [1999] Family farm mortgaged, become solvent. MN credit corp commenced foreclosure agreement under prov act, but farms had been granted stay under federal act. Credit corp. waited 90 days, continued without refiling new application. Family brought action. Operational incompatibility at level of what Ct is being authorized to do … counts as express contradiction SCC held that express contradiction; federal paramountcy triggered Bank of Montreal v. Hall [1990] Pulling away from liberal, non-restrictive idea of what conflict is Farmer has federal loan from bank to buy farm equipment. Bank Act makes it easier for farmers to get loans, but if farmers default, banks can seize equipment Provincial legislation protects debtors from having their property seized by creditors. Before assets seized, creditors have to show that money is owed and is defaulted on, and then have to serve notice. In BMO case, farmer says bank did not follow provincial legislation by giving him adequate notice so liability is cancelled Bank not obliged to comply with provincial law b/c "express contradiction" paramountcy. Supposedly this is an application of Multiple Access … but couldn't bank have complied with provincial laws? Possibility of dual compliance! Justification: Parliament's intent – easy lending terms balanced with easy seizure To contend/comply with prov legisl would frustrate federal purpose, and when this is the case, dual compliance is impossible Thus, prov legisl inapplicable Law Society of BC v. Mangat [2001] R not a lawyer but representing people in immigration proceedings for a fee Provincial laws say only lawyers can charge a fee Gontheir says this is double aspect area, but can coexist unless there is a conflict There is conflict here b/c dual compliance impossible Looks at federal intent. Terminology from Multiple Access but diff reasoning Paramountcy 20 Spraytech v. Hudson (Town) [2001] Charged for violating bylaw re pesticide use, which is in conflict with federal legislation. Ask prov legislation be declared inoperative. Ct says no conflict – fed law is "permissive" not mandatory. Can comply with both simply by not using pesticide Straight-up application of Multiple Access case Difference b/t inoperability and inapplicability: Inapplicable: permanently read down Inoperative: suspended as long as federal law is in place; if federal law repealed, provincial law is operative IJI with one piece of legislation, paramountcy with two pieces of legislation in conflict Husky Oil Operations Ltd. v. MNR [1995] Use of IJI test – "undertow of the dominant tide of paramountcy" SK Workers' Compensation Act cannot apply to bankruptcies if it would subvert federal Bankruptcy Act Use of IJI and not paramountcy Canadian Western Bank … again #2 Banks challenging insurance legislation out of AB Banks under federal jurisdiction, ask Ct for IJI or paramountcy so that legislation not constitutionally applicable (IJI) or not constitutionally inoperative (paramountcy) Discussion of IJI: as FRU, immune b/c affected vital and important part of their operations Key points to take from this: o Good reason to have IJI – Ct confirm its importance textually and in relation to principles of federalism o IJI protects both provincial and federal legislation in theory, but recognize that only used federally in practice o Say IJI inconsistent with dominant tide of constitutional doctrine, which is pith and substance and constrained approach o Sweeping immunity that banks request is not acceptable, would allow IJI to exceed its proper and restrictive limit. Would frustrate pith and substance and double aspect doctrines o Ct will apply IJI with caution. Extensive use uncertainty (each head has core?), not functional, creates legal vacuum (can be granted even when level of govt does not have any legislation in place), subsidiarity (decisions made best at level of govt closest to what it'll affect e.g. local) o Paramountcy always possible o Ct makes more difficult to use IJI after Bell Canada #1: i) substitute "impair" for "affect" to increase severity of impact, ii) para.77, reserve IJI to situations when its been applied in past cases or narrow new circumstances in which it is indispensible or necessary Operability: The Paramountcy Doctrine (FEDERAL) PARAMOUNTCY If successfully invoked, creates exception to doctrine of incidental effects (Ct will tolerate overlap only to point of conflict) 21 Only when law is valid and when conflicts between laws, not b/t jurisdictional heads of power Constitutional Act, 1867, silent on what happens; this problem not foreseen Provincial law becomes inoperative, federal law is paramount o Prov law suspended in areas of overlap only Two steps to applying paramountcy: 1) Look at each law to see if it's valid – use pith and substance, incidental effects, validity etc. If one is not valid, no need to go further 2) Is there a conflict between two laws? SCC gives number of answers on what constitutes conflict, each has underlying principles about what level of overlap is acceptable Multiple Access v. McCutcheon … again #2 Double aspect: both laws valid Dickson J. finds cases that support narrow application of paramountcy e.g. impaired driving – different blood alcohol levels, must adhere to lower standard "Operational conflict" – is it possible to comply with laws at same time? Or is compliance with one an automatic non-compliance with other? (If you can comply with both by complying with stricter, then no conflict and no need for paramountcy. Allows overlap) In this case, laws are so identical that there is no operational conflict – good example of modern paradigm Move away from Privy Council's "occupying the field" test Ross v. Registrar of Motor Vehicles [1975] Change in Ct's l/t attitude in tolerating overlap License suspended for impaired driving except during work hours (federal) vs. license suspended for 3 mo (provincial) Ross argues: s.21 of ON law conflicts with Criminal Code s.21 is inoperative J finds both laws intra vires, finds CC did not allow trial J to have jurisdiction (nonConstitutional) Looks at Australian ruling on paramountcy – must consider intention of statute (p. 258) Case shows Ct will tolerate both prov and federal law within a field of human activity. This overrules old Privy Council rule on "occupancy of field" Odd decision – did intend to let J make these kinds of orders Rothmans v. SK [2005] Prov legislation – no promotion at all. Federal legislation – Tobacco Act s. 19 says can't promote tobacco products anywhere but s.30 says can display it in retail circumstances and notice of price/availability Ct says no conflict, but gives important summary of paramountcy o Paramountcy only applies when can't comply with both o Reading down of Multiple Access Sets out test – ** test for frustration of federal intent ** is independent of dual competency o Is there possibility of express contradiction? o Nonetheless, is the federal intention frustrated … if so, find conflict o ** Impossibility of dual compliance test ** is just one way of showing federal intent o Can show that Ct/state organ cannot comply with both Pressing public health concern; SK legislation furthers two key objectives of fed legislation, amplification and not conflict 22 Tobacco company unsuccessful on both tests A few other key points: o Co. argued that they were granted positive entitlement to display, not merely permitted to do so. SK legislation would take this away. Ct said this was unacceptably broad reading o "Occupying the field" test – refuses to find that only fed govt intended to occupy the field. Ct should be reluctant to infer that prov legislation conflicts with fed legislation. Parliament should be required to explicitly state intent to occupy field Canadian Western Bank … again #3 IJI used more restrictively – "the undertow" Question of incompatibility w/ paramountcy Ct will err in favour of not finding conflict Ct finds AB insurance is valid and so is federal (pith and substance analysis) FRU subject to prov legislation Reject IJI (insurance not vital element of banks) Turn to paramountcy, this does not apply based on facts of case No frustration of federal purpose Reference re Employment Insurance QC's own maternity and employment benefits Unable to negotiate; went to Ct QC won at CA Concern from women's groups in other provinces – if fed govt pulled out, they'd be left with nth of provinces decided not to give anything s.36 of Supreme Court Act gives AG right to appeal straight to SCC Start with pith and substance, not water-tight compartments, reviews of double aspect and necessarily incidental. Progressive interpretation Ct consider full entry of women to workforce – take this into account Good example of asymmetric federalism Peace, Order, and Good Government Preamble to s. 91 -- the fed gov’t has the power “to make laws for the Peace, Order and Good government of Canada in relation to all Matters not coming within the Classes of Subjects by this Act assigned exclusively to the Legislatures of the Provinces” These words set up what is known as the POGG power. There have been two ways of reading these words. 1. The general theory of POGG Fed govt had all jurisdiction except those specifically granted to prov From Bora Laskin, who was strong centralist Russell v. The Queen (1882) Challenge to federal temperance legislation as being outside federal jurisdiction Temperance not listed in s.92, so determined to be "of national concern" without further justification or analysis 23 Russell approach has been overtaken by other interpretations of the words of s. 91. The general theory of POGG is now pretty much discredited and has been replaced by what is called the residuary theory of POGG. 2. The Residuary Theory of POGG This is the theory of POGG that remains in play today. The idea is that POGG is a separate and additional head of power within s. 91. Not merely a “mere grammatical prudence.” If not in s.91 or 92, then perhaps under POGG power History of POGG…. When we look back at over one hundred years of jurisprudence, it is possible to assert that this jurisprudence has resulted in the development of three distinct branches to the POGG power. Now the root for these branches of POGG can't be found in the words of s. 91. It is solely a judicially created interpretative scheme. The three branches are the gap branch, the emergency branch, and the national concerns/dimensions branch. The gap branch of POGG is relatively uncontroversial...extends to things which can be characterized as "drafting oversights," things that the drafters inadvertently forgot to include....covers things that are so obviously federal that very few will contest their characterization as such, but which don't appear to fit into the existing list of heads of power...remember principle of exhaustiveness (= everything needs to lie somewhere) e.g. incorporation of companies for purposes broader than provincial ones Important to distinguish from areas of jurisdiction that are historically new...something that is historically or conceptually "new" has not been left out through oversight... e.g. computers, internet, aeronautics cannot be drafting oversights The other two branches of POGG under its residual theory are the emergency and national dimensions branches... Look at some of the cases that provide early indications of what these might or might not be… AG Canada v. AG Ontario (Labour conventions) (1937) Reference about the validity of the Limitation of Hours Work Act, The Weekly Rest in Industrial Undertakings Act, and the Minimum Wages Act.... --federal statutes enacted to implement Canada's treaty obligations...feds argued, among other things, that they have jurisdiction over matters contained in international treaties the fed executive has entered into...even if otherwise the matters fall within prov jurisdiction... JCPC rejects this argument...stating that "the Dominion cannot, merely by making promises to foreign countries, clothe itself with legislative authority inconsistent with the constitution which gave it birth" --feds also argue that jurisdiction didn't flow only from treaty-making power but also from fact that legislation concerned matters of such general importance as to have attained "such dimensions as to affect the body politic" or to have "become matter of national concern". This is rejected soundly by the Ct. 24 The Ct states that line of cases which refer to such things as "abnormal circumstances", "exceptional conditions", standard of necessity", "extraordinary peril to the national life of Canada", an "epidemic of pestilence" are the conditions when fed gov't can override normal distribution of powers in Constitution. Famous quote:"While the ship of state now sails on larger ventures and into foreign waters she still retains the watertight compartments which are an essential part of her original structure." (p. 122) Good example of restrictive era of POGG AG Canada v. AG Ontario (The Employment and Social Insurance Act) (1937) Validity of fed Employment and Social Insurance Act in question...unemployment insurance.... JCPC rejects argument that within fed jurisdiction because of special importance of unemployment insurance in Canada...points to facts that present Act does not purport to deal with any special emergency but refers to general world-side conditions, its operations are intended to be permanent and Ct does not accept existence of any special emergency. From these cases see two things, then: 1. 2. rejection of notion of national concern to locate legislation within opening general words of s. 91 conditions for application of POGG emergency power are as follows...situation must be exceptional or abnormal, must be a special emergency, legislation must be temporary rather than permanent...address emergency then cease to operate...also looks like the onus will be on the gov't to prove that an emergency exists... These decisions came under heavy criticism. The exception to this negative attitude toward the expansion of POGG was wartime legislation...was usually sustained under an emergency justification...we see this in the Japanese Canadians case Co-operative Committee on Japanese Canadians --Case arose in context of one of most shameful moments in Canada's history—the internment and deportation of Japanese Canadians... --related to orders-in-council Dec. 15/45...end of War...deport people of Japanese ancestry falling into certain classes...was this ultra vires fed gov't? --purport to have been made under the authority of the War Measures Act, passed by Parl in 1914... --Dec. 28, 1945, gov't passed new order pursuant to national Emergency Transitional Powers Act providing that all orders made under War Measures Act should continue in force...so that orders in council are now in force by virtue of the National Emergency Transitional Powers Act --JCPC upholds the orders in council...upholds under POGG...in so doing revives notion of fed emergency power... 25 --three factors stipulated: 1. would need very clear evidence that an emergency has not arisen or that the emergency no longer exists to justify the judiciary overruling Parl that exceptional measures are required...onus put on complainant...deferential stance of the JCPC 2. not for judiciary to consider the wisdom or propriety of policy in emergency leg...exclusively a matter for Parl 3. nor will judiciary be concerned with whether leg will be effective So, wartime emergency cases remained exceptions to general restricting of fed emergency power under POGG...no exception to denial of national concern branch Canada Temperance Federation (1946) AC 193 Watershed case Dealt with the same fed. temperance legislation upheld in Russell...was a direct challenge to Russell—challenger sought to have the Ct overrule Russell...made two arguments: 1. Russell was wrong because not based on emergency 2. Or, case wrong because if it was based on emergency, the emergency of drunkenness was now over Court surprised everyone by refusing to overrule Russell...went on to say that POGG power not confined to emergencies...Russell not about a national emergency...ct in this case stated that if the subject matter of the legislation goes beyond the local or provincial concern or interests must from its inherent nature be the concern of the nation as a whole, then it will fall within the federal POGG power...also expanded the scope of POGG power by recognizing the power to legislate for the prevention of an emergency... --this formed the basis for a number of cases in the seventies handed down by the SCC, now the final ct of appeal, which consolidated the national dimensions branch of POGG...so that in fact it began to play a larger role than the emergency branch...extended to matters such as aeronautics, the national capital commission... --see this in the note in your case material discussion of Johannesson and Munro... Ref Re Anti-Inflation Case Temporary act with purpose of controlling runaway inflation Scope: controlled increases in profits and prices (clearly in prov legislation) Legislation did not mention emergency but did mention national concerns about inflation Ct relied on this Surprisingly, Ct found legislation justified under emergency branch of POGG Why we study this case: last word on emergency branch and gives some info on national concerns branch Q. What constitutes an emergency? Laskin's test: (Prof Young's 8 points) i) "Rational politician test" = Parliament must have rational basis for concluding there is an emergency o Can be established by looking at extrinsic evidence o In this case, use of this evidence was unprecedented. Previously, Ct only looked at text of statutes 26 o Deferential; burden on challenger to show no rational basis ii) Crisis language iii) Doesn't matter that Parliament only addressing small part of emergency iv) Doesn't matter that provinces can opt in/out v) Preamble didn't mention emergency, said there was "serious concern" and that's enough vi) Doesn't matter if govt doesn't act immediately vii) Doesn't matter if legislation does not effectively address the problem viii) Legislation must be temporal Beetz's dissent Emergency Branch Agrees with Laskin that emergency branch and national concerns branch are separate within POGG. Each has different role with diff concerns o National concerns: works as if certain heads of power were permanently added to s.91, has boundaries o Emergency branch: provides temporary extension of federal jurisdiction, knows no limits Would not hold anti-inflation under emergency branch o In other situations, Ct can't find emergency unless govt explicitly declares it is. No ritual words, but have to indicate sense of emergency o Economic emergency can suffice o Doctrine of paramountcy o Can take preventative action o Language that Parliament uses is not sufficient National Concerns Branch Beetz gives restricted version of test (expanded in Zellerbach) Criteria are important b/c permanent transfer to federal jurisdiction o i) matter that legislation deals with has to be new e.g. aeronautics, radio inflation is not new o ii) matter has to have degree of unity to make it distinct from provincial matters and indivisible has a boundary, which is important b/c permanent. Only giving federal govt a certain amount of jurisdiction to avoid encroachment not true of inflation o iii) matter does not effectively swallow up provincial legislation do not give too much power not true of inflation; little would be left over for provincial jurisdiction K. Swinton, The Supreme Court and Canadian Federalism Re Anti-inflation really exhibits different visions of federalism under Laskin and Beetz Laskin: strong centralist, judicial activism Beetz: provincial rights, judicial restraint 27