Melbourne: City of Words - Victoria University | Melbourne Australia

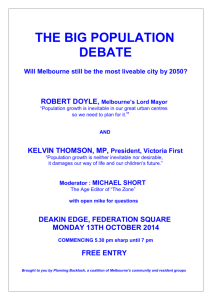

advertisement