SlammedByWired

advertisement

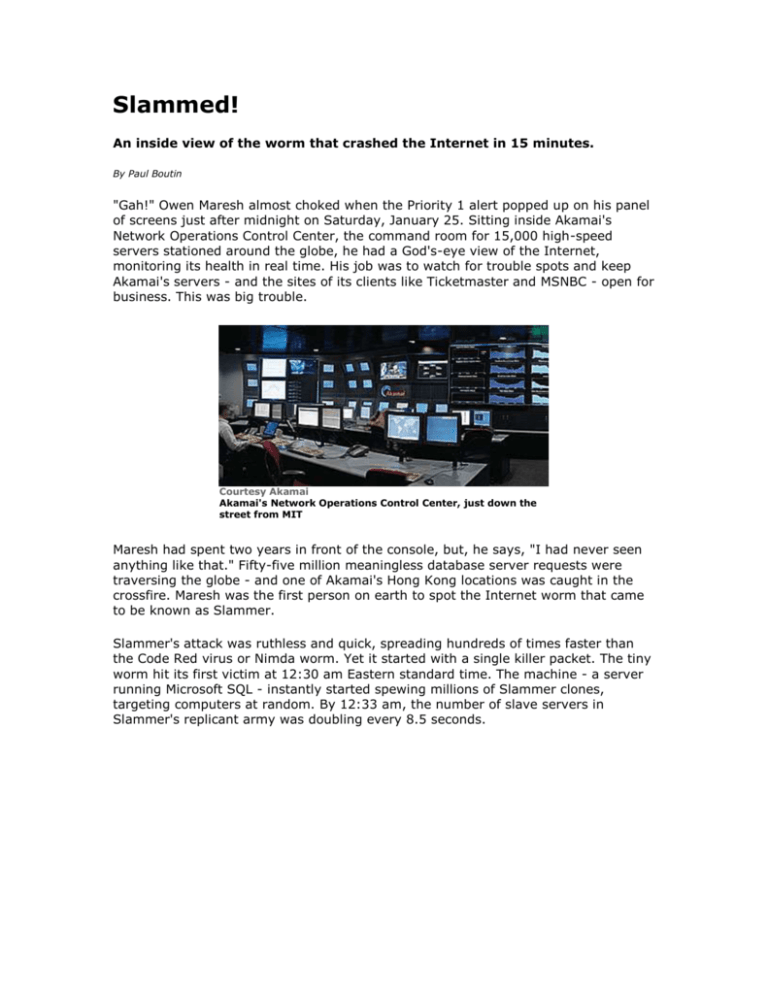

Slammed! An inside view of the worm that crashed the Internet in 15 minutes. By Paul Boutin "Gah!" Owen Maresh almost choked when the Priority 1 alert popped up on his panel of screens just after midnight on Saturday, January 25. Sitting inside Akamai's Network Operations Control Center, the command room for 15,000 high-speed servers stationed around the globe, he had a God's-eye view of the Internet, monitoring its health in real time. His job was to watch for trouble spots and keep Akamai's servers - and the sites of its clients like Ticketmaster and MSNBC - open for business. This was big trouble. Courtesy Akamai Akamai's Network Operations Control Center, just down the street from MIT Maresh had spent two years in front of the console, but, he says, "I had never seen anything like that." Fifty-five million meaningless database server requests were traversing the globe - and one of Akamai's Hong Kong locations was caught in the crossfire. Maresh was the first person on earth to spot the Internet worm that came to be known as Slammer. Slammer's attack was ruthless and quick, spreading hundreds of times faster than the Code Red virus or Nimda worm. Yet it started with a single killer packet. The tiny worm hit its first victim at 12:30 am Eastern standard time. The machine - a server running Microsoft SQL - instantly started spewing millions of Slammer clones, targeting computers at random. By 12:33 am, the number of slave servers in Slammer's replicant army was doubling every 8.5 seconds. Courtesy Akamai Akamai's Network Operations Control Center Akamai's network is heavily automated, with redundant systems at every level. It's specifically designed to weather the most severe Internet storm. Others are not so robust. So as Akamai's DNS servers automatically flipped Hong Kong out of service, Maresh and his coworkers began calling and emailing fellow night owls at ISPs worldwide to warn them of the tsunami of traffic. Too late. BITZKRIEG! 00:55:00 EST 01:00:00 EST Courtesy Akamai The Akamai network polls itself continuously for trouble spots. The lines trace the escalation of By 12:45 am, huge sections of the Internet began to wink out of existence. Net Access Corporation, one of the Northeast's largest ISPs, sent out an early SOS: "Nearly half our ports are in delta alarm right now." Up on the big screen, Maresh could see backbone carrier Level 3's transcontinental chain of routers trying to find working paths to the rest of the world - and failing. Three hundred thousand cable modems in Portugal went dark, and South Korea fell right off the map: no cell phone or Internet service for 27 million people. Five of the Internet's 13 root-name servers - hardened systems, all - succumbed to the squall of packets. Corporate email systems jammed. Web sites stopped responding. A Linux specialist in Manhattan spammed his colleagues in uppercase to make it clear he was screaming: "MS SQL WORM IS DESTROYING INTERNET - BLOCK PORT 1434!" But by then Slammer had knocked out more than just the Internet. Emergency 911 dispatchers in suburban Seattle resorted to paper. Continental Airlines, unable to process tickets, canceled flights from its Newark hub. jammed server-to-server connections. By the time the news made Slashdot, seven interminable hours later, network engineers the world over had been paged from their beds to man the bucket brigade. Lost revenue spilled over halfway into the next week. Total cost of the bailout: more than $1 billion. Six months later, we still don't know who did it or when it will happen again. But we can dissect the Slammer worm and read the prophecy in its entrails: In the future, every blackhat will have 15 minutes of fame. How Slammer Works Slammer owes its speed to UDP, an Internet protocol that's lighter and quicker than the TCP used for Web sites, email, and file downloads. TCP requires sender and receiver to acknowledge each other in a handshake before exchanging information; UDP can carry a message in a single, one-way packet. Microsoft's SQL Server 2000 software has a UDP-powered directory service that lets applications automatically find the right database. Moreover, SQL code comes built into other programs the company sells. Many Slammer victims didn't even realize they were running SQL. The worm takes advantage of a common software bug called a buffer overflow. Buffers overflow when a data string is written into memory without its length being checked by the program. If the string is too long, the tail end of the data overwrites the program's own code. The genius of Slammer is how it uses an attack on just one type of software as leverage for a general attack on the Web itself. Machines infected by the worm swiftly spam the Net with randomly addressed traffic, hitting other vulnerable servers. As the number of computers spewing Slammer packets rises, the situation reaches critical mass, potentially creating a denial of service attack on all 4 billion IP addresses on the Net. Sounds crazy, but Slammer is fast enough to pull it off. Slammer's code is a set of instructions as simple as "Lather, rinse, repeat." The program itself is only 376 bytes, not much longer than this paragraph. Yet its design reveals a sophisticated knowledge of computers and the Net. Here's a step-by-step guide. STEP ONE Get Inside Slammer masquerades as a single UDP packet, one that would normally be a harmless request to find a specific database service. The first byte in the string - 04 - tells SQL Server that the data following it is the name of the online database being sought. Microsoft's tech specs dictate that this name be at most 16 bytes long and end in a telltale 00. But in the Slammer packet, the bytes run on, craftily coded so there is no 00 among them. As a result, the SQL software pastes the whole thing into memory. Courtesy of Brandon Creighton STEP 1: GET INSIDE Brandon Creighton STEP TWO Reprogram the Machine The initial string of 01 characters spills past the 128 bytes of memory reserved for the SQL Server request and into the computer's stack next door. "Stack" is programmer-speak for an orderly list of information the computer shuffles to remind itself what to do next, like tidy paperwork on a desk. The first thing the computer does after opening Slammer's too-long UDP "request" is overwrite its own stack with new instructions that Slammer has disguised as a routine query. The computer reprograms itself without realizing it. STEP 2: REPROGRAM THE MACHINE Paul Boutin (paul@paulboutin.com) is a columnist for Slate. Page 2 >> Slammed! (continued) STEP THREE Choose Victims at Random Slammer generates a random IP address, targeting another computer that could be anywhere on the Internet. To randomize, Slammer deploys a time-honored programmer's trick: It looks up the number of milliseconds that have elapsed on the CPU's system clock since it was booted and interprets the number as an IP address. Courtesy of Brandon Creighton STEP 3: CHOOSE VICTIMS AT RANDOM STEP FOUR Replicate The envelope is addressed, now it just needs to be stuffed. Slammer points to its own code as the data to send. The infected computer writes out a new copy of the worm and licks the UDP stamp. Courtesy of Brandon Creighton STEP 4: REPLICATE STEP FIVE Repeat After sending off the first tainted packet, Slammer loops around immediately to send another to a different computer. It doesn't waste a single millisecond. Instead of making another call to the Courtesy of Brandon Creighton system clock to get the time, it just shuffles the bits STEP 5: REPEAT of the IP address already in memory to create a new one. Slammer's one bug is buried here: The reshuffling leaves a few digits in the address unchanged. It hardly matters, though, since the computer is now spewing packets as fast as its network cable can carry them away. A home PC could cram a couple hundred copies onto its broadband link every second. Corporate data centers became nasty breeding grounds, launching tens of thousands per second.Slammer commandeered just 75,000 SQL machines. But because it replicated so fast, the worm was able to take down millions more, kicking them offline with a flood of meaningless traffic. CISCO INFERNO: Courtesy Akamai This bar chart reflects the Slammer-driven leap in network congestion, specifically the slowdown in server-to-server routes. Abnormally sluggish links are yellow, gridlocked ones are red. The intensity of the color indicates the degree of overload, while the height of the bar shows the number of jammed routes. The maps detail chokepoints in the first hour Slammer hit; this plot, measuring roughly two days, reveals that the worm took 24 hours to be stamped out. AS THE WORLD CHURNS: Courtesy Akamai Border gateway protocol notices are a leading indicator of Internet traffic jams. As less data gets through, routers chur out more notices. This chart shows activity for North Americ (green), Asia (red), and Europe (blue). In relative terms, Europe and Asia have less churn – but only because they have fewer networks tied to the Net. When Slammer hits, BGP churn skyrockets. At right, America maxes out almost instantaneously at 12:45 am EST. Asia peaks three hours later. Europe hits its high on Saturday morning local time. The Fire Next Time Security specialists have long harbored nightmare scenarios of a "Warhol worm" that could crash the Net in 15 minutes. Slammer proved they weren't dreaming. No months of reconnaissance, no compiled lists of vulnerable computers, no massive server farm required to launch the attack. Just one packet - UDP is definitely the way to go. The scary truth is there's plenty of UDP software waiting to be hijacked by a middling programmer. Kazaa. Xbox. How about the code that controls the domain-name system itself? The 350,000 DNS servers that link our computers form an interconnected UDP network that we can't do without. A Slammer-like attack on DNS would bring the Internet to a standstill in less time than it takes to read this article. Lucky for us, unlike Microsoft's Swiss cheese SQL Server, the open source DNS code doesn't have any such holes. Or does it?