AP Notes Mod 22 Operant Cond

advertisement

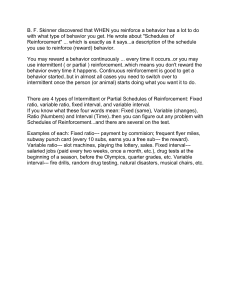

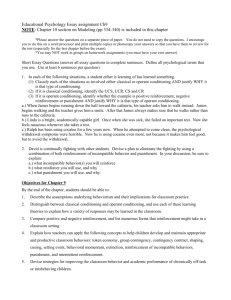

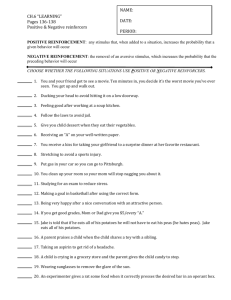

AP Notes Module 22: Operant Conditioning Thorndike’s Law of Effect is IMPORTANT! A law in science refers to an idea that is true at all times—like Newton’s law of gravity or the law of thermodynamics. There are very few laws in psychology because psychology is such a young science & behavior is quite complex and difficult to discuss unequivocal terms such as laws. Thorndike’s law of effect is an example of a way in which behavior is rewarded, it continues, and when a behavior is punished, it discontinues. B.F. Skinner’s work with animals spurred research and work in training all kinds of animals to serve useful purposes. In WW II, Skinner trained pigeons to guide missiles to their targets. While the military at that time didn’t buy into Skinner’s pigeons (nobody wanted to admit they used ordinary pigeons to win the war), these animals were more effective than humans at identifying their targets. Jim Simmons, Ph.D., a Navy scientist, trained pigeons for the Coast Guard to conduct search and rescue missions. While humans were 38% accurate at identifying targets, pigeons were 93% accurate—and they didn’t get bored after being on duty for hours. Skinner not only trained animals in operant chambers (Skinner boxes), he also developed a device called an air crib, which was designed to house infants to train them. Is this ethical in your mind?? Delayed gratification is a skill many parents want their children to have. People who can delay gratification are able to achieve more in life. Consider the following questions in regards to “real life”: What types of “real world” rewards occur on a delayed schedule? Did you learn to wait for rewards? Why or why not? Does the media encourage people to delay gratification? Why or why not? **There are ONLY two main types of reinforcement schedules—continuous and partial (intermittent) schedules. The different ratio and interval schedules described in the text are all partial schedules. Continuous schedules are excellent for training behavior quickly if you want quick results, reinforce after every desired behavior occurs. The problem with continuous reinforcement, however, is that is also extinguishes quickly. Once the reinforcement ends, so does the desired behavior. If you want the behavior to stick, you’ll need to transition to a partial schedule, which is more resistant to extinction. The pattern of reinforcement shown during a fixed-interval reinforcement schedule is called scooping. Animals and people trained on this schedule tend to wait until the time interval is drawing near before performing the behavior, which results in the scooped look of the graph charting the behavior. Many teachers give grades on a continuous reinforcement schedule, awarding points for every assignment students turn in. Consider the impact o this type of reinforcement on learning: Do you get grades for every assignment you turn in? Why or why not? How do you feel if a teacher doesn’t give grades for every assignment? What unintended consequences might occur when teachers use continuous reinforcement? Be sure you can discriminate the difference between interval and ration schedules. Interval schedules: involve a time element—time must pass before reinforcement will occur. The subject must be behaving at the right time to get reinforcement. Ration schedules: are dependent on the behavior itself—a certain # of behaviors are needed before reinforcement will occur. Variable-interval schedules are difficult to remember because they are simply about waiting until a behavior occurs before reinforcement is given. Students have to be continuously studying and waiting for a quiz to occur on this schedule. Help students remember this by reminding them that an interval schedule requires the subject to be performing the behavior when the reinforcement comes. The distinction between negative reinforcement and punishment is one of the most often confused concepts in psychology. See the following! Negative reinforcement: encourages behavior. When something unpleasant ceases, the behavior that caused it to stop is reinforced. Punishment: discourages behavior. Behavior that is unwanted is punished, making it less likely for that behavior to continue. Positive punishment is NOT a desirable type of punishment. Rather, the words “positive” and “negative” when referring to reinforcement and punishment mean “adding” and “subtracting” respectively. When we add a punishing stimulus for a behavior, then it is considered positive punishment. CONNECTION: punishment can be connected to classical conditioning through spanking; it can lead to an association between the parent and pain: US: spanking CS: Parent’s upraised hand that does the spanking UR: fear and crying from pain o If the parent’s upraised hand is paired often enough with the pain of a spanking, children can begin to associate the gesture with the pain and fear their own parents. This unintended consequence can lead to children not trusting their parents at an early age. Recall an early childhood memories of learning how to do something, like riding a bike. How did you learn? What operant conditioning techniques did your “teacher” use with you? Even though the original studies on cognitive maps were done with rats, people form cognitive maps in many circumstances. For instance, ninth graders first coming to the high school often take time in the summer to walk through the building, forming a cognitive map of the school. When they arrive at school for the first day, they will navigate the school better than those students who don’t take time to learn the layout during the summer (don’t forget this technique when you go to college!). Biological predispositions work similarly with operant and classical conditioning. Only certain behaviors are likely to elicit responses. You can teach people and animals a wide variety of behaviors, but you can’t teach them any behavior you desire. Please don’t overlook the concept of instinctive drift. Since this is not a bold word, you miss this important concept. Even trained animals act naturally, regardless of whether a trained behavior is being reinforced. Skinner’s research on “superstitious” behavior in pigeons can illustrate both the power of reinforcement and its application to everyday life. According to Skinner, a superstitious behavior is a response that is accidentally reinforced— that is no prearranged contingency between the response and reinforcement. Because the behavior and reinforcement occur together, the behavior is repeated, and by chance, is again followed by reinforcement. This process may explain why we carry a half dollar as a good luck piece, wear the same slacks when taking tests & step over cracks in the sidewalk. Fables about students conditioning their teachers’ behaviors are legion. You have perhaps heard and even told your class how students have shaped their teachers to stand only in one corner of the room or face in one direction. W. Lambert Gardiner tells, tongue in cheek, how one class laughed more uproariously a their teacher’s jokes as he moved toward the right side of the room until they were able to condition him right out the door. (OK SO DON’T TRY THIS WITH ME!!) Psychologist David Allison of Columbia University reported an application of operant conditioning principles to both weight control and leisure management in children. The researchers created TVs that turned on and stayed on when the children pedaled a stationary bike. Children who had to pedal to watch TV biked an average of an hour a week while the others biked an average of only eight minutes. The pedal group watched one hour of TV per week and decreased overall body fat, while the non-pedal group watched 20 hours and saw no difference in weight. Use table 22.4 to emphasize the differences between classical and operant conditioning. Students often get these two paradigms confused, so looking at this table will be helpful! Biofeedback is one way in which learning and biopsychology intersect. By using cognitive strategies to help control our physical reactions, we can learn how to relax. This type of therapy can be helpful for people with stress-related illnesses.