Word Document Format

advertisement

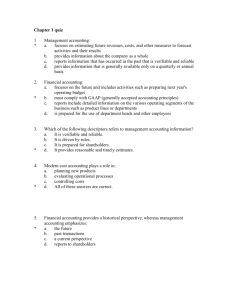

February 2005 Index 1 2 Messages: Managing Partner’s message Comment: On holy cows and shareholders contracts 3 Comment: The way of the Dragon 4 5 6 (The sanctity of Joint Venture Agreements in Indian law) (The Layman’s guide to the Chinese legal system) Comment: Contrived crimes Lifestyle: (Conversion of commercial disputes to crimes in India) In quest of Kinnaur (A road journey through the inner Himalayas) Initiative: Our workshop schedule 1 1 5 8 11 17 (Workshops for the business community) Managing Partner’s Message As our country continues to progress rapidly through the New Year, we have been privileged to share in the excitement of a society in the midst of change. Here are some of the things that we have witnessed in the last two months: 1. Our Senior Partner Mr. P.S.Dasgupta and the Swiss law firm Homburger have steered Holcim’s acquisition of Ambuja Cement. This is by far the largest Mergers and Acquisitions deal that India has ever witnessed. It has also raised complex issues pertaining to India’s Takeover Code. Once the transaction achieves culmination, we hope to have the opportunity to bring some of our learning to our readers through the pages of Ensouth. 2. Over the years, we have advised Indians and foreigners on a multitude of joint venture transactions. We have also dealt with the consequences of those that have gone bad. This issue has acquired a special significance in the face of the Ambani imbroglio. Ensouth now addresses the question of enforceability of shareholders agreements in Indian law. 3. In December last year, I spend one week in Shanghai and spoke to a cross section of business and legal professionals. Ensouth carries this 1 time a simplified overview of the Chinese legal system as seen through the eyes of an Indian lawyer. 4. Notwithstanding the tremendous progress India has made towards transforming itself into a civil society, business continue to carry the perception that crimes can be contrived out of commercial disputes. This time, Ensouth examines if this is true. 5. In our leisure section, we reproduce one of the great Himalayan journeys, into the land of the celestial ‘Kinnars’, north east of Shimla, reproduced from the article published in ‘Namaskaar’ magazine. 6. Finally, in continuance of the successful interactions we have had with the business community in the last few months, we share with you our workshop schedule for the next three months. 2. Comment-1 The following column was printed in the December 27th, 2004 issue of Business World. Of holy cows and shareholders contracts The sanctity of Joint Venture contracts in Indian Law Ranjeev C Dubey It amazing how the seemingly easiest legal questions are sometimes the hardest to answer. Other than a 100% buy out, every M&A transaction generates a shareholders agreement by which company owners bind themselves to special rights and obligations. How far these agreements are enforceable in Indian law is the questions I seem to answer most often at the commencement of every other M&A transaction. It’s a fair questions: after all, the relationships between co-owners will most likely be the single most dominant factor influencing the future of the corporate entity. To understand this issue, let us first examine what a shareholders agreement typically does. In Indian law every shareholder is at complete liberty to exercise his shareholder’s ‘power’ as he sees fit: he has absolutely no obligation to protect the ‘interest of the company’, however that exotic gobbledegook is defined. This means that if it serves a shareholder’s purpose, he can take the company down to push his own agenda; brinkmanship in shareholders disputes being a very good example. Given this legal reality, how then is one to protect value in the company? The answer is a shareholders agreement that sets out the limits within which shareholders may exercise their shareholders rights. 2 In practical terms, every shareholders contract provides the manner in which a company is run and this includes (1) the constitution of the board, (2) quorums of board meetings, (3) decisions the board may not take without the consent of all partners, (4) quorums of shareholders meetings, (5) decisions a shareholders meeting may not take without consent of all partners, (6) solutions if the board or the shareholders are deadlocked, and (7) a mechanism by which partner disputes may be resolved without eroding company value. In Indian law, such an agreement does not sufficiently protect value in a company. Courts here have ruled that while partners in a company may be bound to each other because they have a signed a shareholders agreement, the company certainly is not. This means that the company, ‘steered’ by the controlling group of partners, can ignore the contract and proceed at its will. What a shareholder contracts then gets you is litigation between partners, but it does not stop the company from doing what it wishes. This means that in practice, shareholders agreement or no shareholders agreement, the majority shareholders can bulldoze the minority One common solution to this problem has traditionally been to make the company a signatory to the shareholders agreement. This works in many jurisdictions but again, not in India and for two reasons. First, any party is free to violate a contract if it is ready to pay the price in damages as a court may some day determine (in this lifetime or the next!). There are any numbers of circumstances where a company may find it commercially wise to breach its contractual obligations and meet a greater agenda. Money does not always compensate a wrong, especially money that does not show up in this lifetime. Second, the Rolta judgment (of the Bombay High Court) has added another twist to this issue by in effect holding that directors have fiduciary duty to a company, not the agreement of the owners. This is a case where by a truncated shareholders agreement to which Rolta Motors was a party, owners of Rolta Motors had agreed that for so long as the Plaintiff had shares in the company; the Board of the Company would be limited to three directors. Subsequently, Rolta Motor sought to induct an additional director on to its Board. On reviewing previous case law, the Bombay High Court held that Directors both drew their rights and their duties from the law and the Articles of the Company alone. Consequently, a shareholders agreement could not be used to restrict the discharge of their fiduciary duty to the Company. This whole business of fiduciary duty to company versus harsh reality of being appointees of the owners has been the bugbear of directors since companies were first conceived and 200 years of legal pronouncements have not sorted this one out. That apart, I can make some sense of this pronouncement in the context of a widely held listed company but how we 3 are to draw a distinction between a company and its shareholders in operational matters when the company has only two owners is frankly too exotic for my nightmares-on-mean-street paradigm. Rolta did make one exception though. It indicated that the court’s decision may well have been different if the shareholders agreement had been written into the Articles of Association of the company. Many M&A lawyers have long taken the view that we need to write shareholders agreements into the Articles of the company but own my reasons for making this recommendation are not Rolta’s. In my experience, a Court will stop a decision that violates the Articles of a Company dead in its tracks but a decision that breaches a contract but is not ultra vires (beyond the powers of) the Company is harder to stop, though the aggrieved party could probably sue and collect some damages if and when the litigation cows finally come home. Rolta has provided additional justification for doing this, because now, by writing shareholders contracts into Articles, we are going to cast a fiduciary duty on the directors to see that this agreement is honored. That gives us lawyers several more people to drag to court and sue in their personal capacity. However, since this is the law after all that we are talking about (need we remind ourselves), this too is not the end of the matter. Section 9 of the Companies Act states that its provisions shall override the Articles of a Company, its resolutions and the resolutions of its directors. It also says that to the extent that the Articles are ‘repugnant’ to the Act, the Articles will be void. So what is ‘repugnancy’? If the Act says it takes two directors to constitute a quorum of a Board meeting but the Articles say one director can constitute a quorum, are the Articles repugnant to the quorum? The courts have held that this is a repugnancy. What if the Articles say you need three directors to constitute a valid quorum of a Board meeting? Is that a repugnancy? The courts have held that it is not. The principle seems to be that additional conditions or more stringent norms are legal but slackening of the Act is not. In simple terms, more is Okay, less is not. Since 3 directors is more restrictive than two, the Articles are legal. Now all this is easily understood in the context of simple numbers but what about something a little more obtuse. How about information rights? The Companies Act both enforces and limits the information directors can demand from a Company. What if a shareholders agreement gives expanded information rights to directors? Is that more or less? I am sure I have no idea. Take another example. Are veto rights to directors to simply overrule the majority on a resolution legal? Put this way, may be not but we need not say it this way: we can say: “the affirmative vote of a director of each party shall be necessary for a board to validly pass a resolution.” It sound better and can be passed of as a more stringent condition but shorn of the rhetoric, 4 what is it if it is not a veto? Since the law requires Board Resolutions to be carried by a simple majority, is this sort of provision more or less? In truth, Indian courts have never definitively answered these questions. All we can do then is console ourselves by saying that in a dynamic world where even settled principles of law get unsettled as times, tides and people change, it may not be worthwhile worrying too much about the legal questions that have not been settled. By which token, for the moment, if an investor in an Indian company gets all the shareholders and the company to sign a shareholders agreement, and then gets it written into the Articles of Association of the Company, I think the investor should be doing alright. 3. Comment-2 The following column was printed in the January 15th, 2005 issue of Business World. The way of the Dragon A layman’s guide to the Chinese legal regime Ranjeev C Dubey Times change and how: early in 2003, most stakeholders of the Indian business community were writing alarmist obituaries to the eminent demise of Indian manufacturing at the hands of the fire breathing Chinese dragon. By Diwali of 2004, we were all speaking of finding synergy between Indian knowledge and linguistic skills with Chinese organizational skills. Before the year was out, I was retained to close a cross border joint venture between an Indian and a Chinese company. I don’t know what I expected to find when I spend a week in Shanghai in December with a group of experienced Chinese lawyers but I am sure I did not expect to learn that China did not have a coherent legal regime in a way that I understand the idea. Without claiming either adequate knowledge of or training in the subject, let me share with you my understanding of the Chinese legal system. Chinese law has no difficulty understanding the idea of a ‘natural person’ – people like you and me – but the concept of a ‘legal person’ – like companies and Hindu Undivided Families – is not well developed. Naturally, the powers, functions and duties of these legal persons remain undefined. Article 41 of the General Principles of the Civil Law for instance stipulates that a legal person must have (1) sufficient funds; (2) Articles of Association; (3) an organization and premises; and (4) the ability to bear civil liability independently. However, there is no general consensus on whether or not legal persons can own, manage and dispose of properties independently. The absurdity can be quite bewildering at times. 5 Take Article 2 of the Law on Industrial Enterprises Owned by the Whole People, which provides that State-owned enterprises must obtain the status of a legal person in accordance with the law and bear civil liabilities as regards the property that the State has authorized it to operate and manage. At the same time, it stipulates that the property of such an enterprise is owned by the ‘whole people’. As I read it, this means that these enterprises shall be entitled to deal with their properties to the extent that the states authorizes them to do so. As a lawyer for a third party dealing with such an enterprise, I would worry a great deal about what is authorized and what is not. More worrying though is the thought that the “corporate veil” does not meaningfully exist in China: there is no clearly demarcated distinction between the company and its shareholders. Actually this whole problem is rooted in a far deeper problem. Remember that not so long ago, China was communist and denied private property rights. While ‘economic’ China, pragmatist as always, has sailed a long distance away from those misconceived shores, ‘juristic’ (or more bluntly ‘rhetorical’) China has failed to keep pace, and has still not accepted the idea of private ownership of property in a constitutionally meaningful way. Article 11 of the Constitution for instance can do no better than state that "the State protects the legitimate rights and interest of the private economy". And what pray is legitimate? And who is to determine whether something is or is not legitimate? My legal training tells me that there is a very clear distinction between what I have a constitutional right to and what the state promises to do for me in some generic amorphous way. India has its directive principles too but I would trust in my fundamental rights a whole heap more. If you think about it, the entire private economy in China is built up on little if any legal foundation. Without the right to own what they do, they really have no right to exist. Which is why private business in China subscribes to less than 1% of official bank credit. What you have then is private business tapping into a national network of underground banks, people who are prepared to lend against highly specious collateral security, people who operate on personal relationships, not on declared lending policy or the economic fundamentals of the borrower. Naturally then, any debate about contractual obligations, contractual comfort, risk profiling or liability indemnification between an Indian company and a Chinese one immediately trans-mutates into a debate about the legitimacy of the Chinese company as a corporate entity, to state nothing of the credibility of its balance sheet. That also opens the door to the larger debate: if we do have a dispute on what the law really is, who is going to resolve it? This is where I made my most amazing discovery yet. Chinese courts are not authorized to interpret the laws of China! China has adopted what is called the principle of legislative interpretation. This is rooted in the idea that those who make the law are in the best position to 6 interpret it. This means that Chinese courts are empowered to implement the law but not interpret it. In truth, I can’t imagine a case where it is possible to apply a law without first asking, “what is the law?” If that is not an interpretation issue, what is? What you have in the result is a dysfunctional system that any smart defense lawyer can spin “interpretation” webs around and defeat a claim. It gets worse. Given the general indifference with which a cohesive logical legal system is held in China, it is no surprise that the Courts function poorly if at all. Courts are not necessarily or even substantially manned by trained legal persons – meaning judges don’t have a law degree – and the rules of procedure are rudimentary. Chinese administrators do not understand the distinction between executive and judicial powers and they are just as likely to knock on the door and start to settle a dispute between private parties without invitation. In practice, untrained petty officials can and do assume jurisdiction to settle disputes without express authority, rules or petition, banana republic style! So who interprets the law then? The Constitution entrusts this task to the NPC Standing Committee. In practice, the NPC Standing Committee is yet to formally interpret any law at all. Even when it has been asked to do so, it has steadfastly refused. NPC Standing Committee’s paralysis has left the courts with the task of applying laws that no one will interpret for them. Since 1981, the Supreme People’s Court of China has issued thousands of pieces of judicial interpretation to guide lower courts but given the reality of ‘legislative interpretation’, it is debatable if these interpretations are legal. How then is a dispute in a cross border contract to be resolved? In China, as in many other countries, the answer is arbitration. Till 1994, China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (“CIETAC”) handled all disputes with cross border implications on an exclusive basis. There were till 1994 two separate systems of arbitration in China: one for domestic economic cases and the other for foreign-related cases. In August 1994, the new Arbitration Act of the PRC established a fairly contemporary system of dispute resolution in arbitration and this applied to both domestic and international arbitration. Following the promulgation of the new Arbitration Act, the General Office of the State Council issued a Notice stating that other arbitration commissions may also exercise jurisdiction over cross border disputes if contending parties so chose. In a flash, the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission and the China Maritime Arbitration Commission, both established under the China Council of the Promotion of International Trade were to the task. CIETAC was really upset. CIETAC asked the NPC Standing Committee to interpret the Arbitration Law and asked two questions: (1) whether the Notice issued by the General Office of the State Council constitutes an administrative regulation; and (2) whether the Notice is in compliance with 7 Arbitration Law. Predictably, NPC has maintained a deathly silence on the issue. It is alarming that Chinese law is unclear on very basic subjects: things that an Indian lawyer would take for granted. What is worse is that there is no functioning mechanism by which clarity can be achieved. Then there is the problem of dispute resolution: whom do you go to for redress and what power do they have? To top it all, even if you get an arbitral award in your favor, there is no clarity on how it is to be enforced. Decree executing courts suffer from the same disabilities as decision-making courts. Where then is the solution? To give China a wide miss and find business opportunities elsewhere? I think not. Profit after all is a reward for managing risk and not for practicing abstinence! Indian business needs to seize the opportunity but it needs to do so understanding the legal issues here, without assuming that China’s legal regime is anything like India’s. In effect, this only means better legal help. At end, here is a little sobering thought: if India has indeed missed the foreign investment bus to China, it sure isn’t because the Indian legal regime is archaic, inadequate or uncertain. 4. Comment-3 The following column was printed in the February 14th, 2005 issue of Business World. On Contrived Crimes The sanctity of Joint Venture contracts in Indian Law Ranjeev C Dubey Condemnable as the event doubtless was, the national feeding frenzy of outage which followed the judicial remand of Bazee’s CEO took attention away from the fact that police ‘victimization’ of business of this order of magnitude remains the exception rather than the rule. What is more dangerous for the business community is the perception that criminal processes can be commonly used in India to settle commercial scores. Consider a contemporary example. The Lord Swaraj Paul of Marlylebone, founder of the Caparo group and a peer of the House of Lords since 1996, now finds himself facing criminal charges in an Indian court as a result of a fairly routine shareholders dispute. UK’s Caparo group holds 60% of the equity of an Indian JV Company, of which Suzuki’s Indian company holds 20% and the ‘Jindal group’ of Companies, headed by M.D.Jindal, holds the balance. Back in 2002, Jindal demanded that he be retained as Chairman for life of the Indian JV Company and made allegations of mismanagement against the Caparo group in granting inter corporate loans to group companies. Allegations of 8 mismanagement in this company are of course quite incredible because it is a very profitable company, appropriate board resolutions were passed before the loans were given and the loans have also long been returned. Jindal took this matter to the Company Law Board and lost. While the CLB petition was still pending, M.D. Jindal filed a criminal complaint before the Metropolitan Magistrate alleging that at a shareholders meeting, Lord Paul “tried to intimidate him and tried to physically assault the complainant”. It bears mention that both men – Lord Paul and Jindal - are more than seventy years of age! He then alleged that Angad Paul called him up after the meeting and threatened to kill him. In another train of allegations, he accuses the entire Board of conspiring to misappropriate moneys by lending them to group companies. Finally, he alleges that the minutes of the Board Meeting were forged because his objections were not recorded. On this basis, Jindal alleges Conspiracy, Criminal breach of trust, misappropriation of Company funds, forgery of board minutes and criminal intimidation against Lord Paul, Angad Paul, the Board of Directors, even the Company Secretary. All this laughable triviality would have been amusing were it not that a court has actually taken cognizance of the private complaint and issued notice on all the accused. At first sight, this seems a damning indictment of the legal environment in which Indian business operates. Is it? As I write, this morning’s newspaper reports that American actor Wesley Snipes lost a bid to get a federal judge to cancel an arrest warrant stemming from an Indiana paternity suit in which a women claims he fathered her son. In any civil society, what will you have a judicial system do if a complaint containing serious allegations against a celebrity is filed? Any system is capable of abuse: should we provide blanket immunity from prosecution or arrest without exception to all shareholders, directors and managers? Will that rule apply to cattle fodder consuming politicians too? You can make a fetish out of cynicism. The question better asked, and one I frequently deal with, is this: “Is criminal process commonly used to achieve commercial ends in India?” My answer is a resounding “no” and I will give my reasons. The normal trigger for a criminal prosecution in India is the ‘FIR’ or First Information Report. In a country where the press is vociferously free, it takes an extraordinarily courageous SHO to record an FIR without good reason. The common Indian allegation is that that the police record too few, not to many, FIR’s. Jindal did not succeed in getting an FIR recorded. Second, why would a business adversary bother with a criminal case unless he can seriously inconvenience or embarrass his opponent? A criminal case that does not result in arrest, bail, harassment or embarrassment is not worth the candle. Arrests are only possible in ‘cognizable’ cases. By their 9 very nature, the technical ingredients of cognizable crimes, and the standard of proof required, is such that it is very difficult to make a credible allegation of a crime in a commercial context. You don’t have a credible criminal case only because you want to contrive one. The truth is that most complainants hell bent on filing criminal cases in commercial matters end up filing motions with magistrates, as Jindal did. In some ways, this route is inherently fairer because at the very inception of the criminal process, a legally trained magistrate examines the allegations in a complaint, the supporting evidence and oral testimonies before he ‘takes cognizance’ and summons the accused. Justice frequently gets done right there. Not always though and it is this gross miscarriage of justice that Lord Paul is now experiencing. Unfortunately, getting summoned by a criminal court in India is a huge inconvenience because every accused must attend every hearing. Being late to reach the court is not an option because warrants of arrest are issued pretty regularly. What are the options? Essentially there are two. First, an accused may apply for permanent exemption from personal appearance and let the case go on. The difficulty here is that to get such an order, an accused must first submit to jurisdiction. This at the very least means some expense and inconvenience in traveling to the court but very likely, it also means a great spectacle. Who wants to be seen to be accused of a crime in an Indian court or deal with attending tamasha? (A indigenous form of expressionist folk theatre) There is an alternative though. Since the early 1990’s, an accused wrongly accused of an offense could approach the Magistrate and ask for recall of the summons. Not any more. In the Adalat Prashad decision late last year, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court has held that once a Magistrate issues summons, he cannot review this interlocutory order. That leaves the accused with only one remedy: to seek to quash the entire proceedings under the inherent powers of the High Court. This is a difficult business. Since a trial is yet to occur and evidence is yet to be produced, the court will assume that all allegations made are true and then evaluate if a crime has been committed. In a country where conviction rates are abysmally low, how are you going to convince a court that a case should not even be tried: that evidence should not even be produced and evaluated? Which takes us to the last of the questions: where the quash remedy fails, what does one do. In truth, compromise is now the only alternative, in Indian parlance, “compounding of offense”. Again, this is no simple matter. Since a crime is an act that vitally impacts society generally, and not just the victim, the majority of crimes cannot be compounded without the permission of the Court, which you may or may not get. 10 Ironically, this rigorous rule hugely protects business from false criminal cases. It is always possible to run into a rabid opponent but in most situations, a business adversary files a criminal case because he expects to generate intolerable pressure and force a settlement. A case that cannot be settled is no tool at all: indeed such a case hampers compromise because it is a counter that cannot be bargained away. It is true that criminal allegations are very powerful and destructive but in a commercial context, what use is a weapon you cannot control? 5. Lifestyle The abridged version of this article was published in the October 2004 issue Namaskaar, Air India’s in-flight magazine. Great Road Journeys Quest for Kinnaur Ranjeev C Dubey Viewing the vast expanse of the Satluj valley from the crow’s nest edge of Narkanda bazaar, two hours east of Shimla, we prepared to commence our discovery of Kinnaur district. After a quick breakfast, we headed out, lapping up the miles as we descended northwards through the Deodar tree line past Kumarsain, till we joined the left bank of the Satluj at Sainj. Turning east, we then ran with the river to a very pleasant surprise by the name of Rampur. Rampur is a picture perfect Himalayan market town, straddling either side the fast flowing Satluj river, where the sound of the waters rushing over the mirror smooth basalt rock is never far away. This bustling prosperous district headquarters, once the capital of the small hill state of Rampur Bushehr, dates its prosperity to events occurring in the 17th and 18th century when these hills experienced a prolonged period of considerable violence between the Gurkhas, Kashmir based Afghan warlords, Tibet and local Rajputs. The eventual eclipse of Gurkha expansionism following the execution of the Treaty of Sagauli with the British only then encouraged Sikh ambition under the able guidance of Maharaja Ranjeet Singh. When Ranjeet Singh’s able general Zoravar Singh took Ladakh and threatened Tibet, Tibet rushed to ring itself with its own buffer states. Rajah Kehar Singh of Bushehr, in exchange for military support, extracted wide 11 ranging trading concessions in perpetuity. As Shimla grew as a seat of British power, much of Bushehr state’s Tibet trade addressed the occupants of Shimla, a trade best commemorated in the Lavi fair which at one time was a show piece of Tibetan Shah Toosh, semi precious stones, handicrafts, horses, yaks and almost everything arriving overland from Kashghar and Yarkand. Rampur today remains a great place to stock up on everything: shoes, ships or sealing wax, cabbages and (Gypsy) Kings! Purchasing ludicrous quantities of fruit at steal prices, we continued our journey north, spanning Jhakri, at the lower limit of the 1020 MW Nathpa Jhakri Hydro-electric Project. At Jeori, we turned north and went 17 km up the mountain to the first of our destinations: Sarahan. Permeated to the core with that mystical magical presence of the spirit of the land, nestling in a thick forest of Oak and Deodar, Sarahan was once the ancient capital of the Bushahr state. Sarahan is the Shonitpur of antiquity, where Krishna fought a pitched battle with its ruler Banasur, a devotee of goddess Bhimakali. Banasur’s daughter Usha fell in love with a prince who appeared in her dreams. Despairing of her obsession, she consulted her mantic friend Chitralekha who recognized the prince as Aniruddha of Dwarka, flew magically to him in the night, abducted the prince in his sleep and performed a gandharva vivah with Usha. Aniruddha was Lord Krishna’s grandson and he was infuriated. A fierce battle ensued, Banasur was defeated but in the end, there was a happy ending, Shonitpur was given as dowry to Usha, and Aniruddha ruled it for a long time. Sarahan’s greatest attraction today is its 800-year-old pagoda roofed wood built Bhimkali temple perched high up overlooking the eastern Satluj valley under the watchful eye of the 5227 m Shrikhand Mahadev peak to the west. It’s a very moody very Himalayan place, beautiful in a simple magical way. The temple is built in the Indo-Tibetan architectural style, and is one of the last few surviving temples made entirely of timber. The origin of the temple is to be found in the Markandya Purana. Legend has it that Durga had promised her devotees that she would liberate the Devtas from the Asuras (which she did in her Bhima Devi aspect) and would thereafter dwell amongst them forever. In the Dwapar Yuga, the saint Bhimgiri visited this place carrying a stick with which he had offered ‘aryadha’ to the goddess. At this place, the stick became exceedingly heavy 12 and he was unable to move it. Interpreting this as a sign, he immediately set out to build a small temple which has grown with the ages. The main temple today is a study of simplicity and beauty. It is accessed through the lower courtyard through six beautiful silver coated doors made by Kinnauri silver smiths during the reign of the Maharaja Padam Singh (1927-47). The pagoda roofs of the main temple have projecting timbers, which end in cornices featuring animistic icons. The sanctum is housed on the first floor and is the abode of the one meter Ashtadhatu (8metal allow) deity surrounding by a parikrama, protected by fine filigree work within which only pujaris step. The second storey of the temple houses a deity of goddess Parvati and is surrounded by other lesser local deities. The entire inner courtyard overflows with bougainvillea and flowering shrubs and the cobbled paving combine under a deep blue sky to form a very tranquil scene of spiritual bliss. This complex also has three other major temples. The first of these, the temple of Raghunath is also 800 years old and was built when Raja Beej Singh defeated and slayed the Kulu raja and took the Raghunath idol as booty. The second, the temple of Narsingh is built in the Shikhara style and houses a marble statute of the lord. Finally, there is the Lankra Veer temple, which curiously is devoid of any deity but has a wooden pole attached with a trishul and prayer flags. There is a deep well in this temple and it is said to have a secret escape door that connects through a long cave to an as yet undiscovered exit. Human sacrifice was normal here in the old days whereafter, it is said, the bodies were thrown into the well. After paying our obeisance at the temple, we spent the rest of the day discovering the beauty around Sarahan. We found green fields waving their celestial message with the gentle breeze, small villages exhibiting that quaint indigenous architectural style, thick forests, and that unique spirit of the very soul of Kinnaur. Amongst the least known districts of Himachal Pradesh, Kinnaur lies between Tibet to the east, Spiti to the north, Kulu to the west and Uttarkashi to the south. It offers a great many picturesque valleys for the adventurous traveler, not least of which are the river valleys of Satluj, Spiti, Baspa, Jaiti and Tirung. The people of Kinnaur claim their roots from the very depth of antiquity. They practice a religion with no name, a mixture of Buddhism and Hinduism, much of it animistic where each village has its own local deity, some of them demons. The Buddhist Lamas hold a prominent position in Kinnauri society and polyandry is still common. The most ancient inhabitants of the area are believed to be the ‘Kinners’, minstrels or heavenly musicians, also sometimes called ‘Gandharvas’, a race of beings half human and half bird, inhabiting a semi-celestial region where earthly saints, once they achieved perfection, consorted with these super beings. 13 Archeologically, it is surmised that a branch of Aryans, called Khashas, penetrated the Himalayas from central Asia through Kashghar and Kashmir to dominate this area about 2000 BC. Later about the 14th century, Bhotia tribes began a mass migration from Tibet giving rise to the unique local culture. Kinnauris today remain great singers and dancers and almost any fair, of which they have one practically every month, is good illustration of this talent. The whole area is well known for its chestnuts, walnuts, pears, apples, apricots, grapes and ‘chilgoza’ pines. Descending back to Jeori next morning, we continued our way north till we came upon the awe inspiring suspension bridge at Wangtu, hanging precariously between the sheer faces of two near vertical cliffs over the raging waters of the river. Although Kinnaur and Spiti were opened to tourist traffic in 1987, a devastating cloudburst in 1998 wiped out five miles of inhabitation and created an artificial lake that wrecked further destruction when it burst. The entire landscape is scarred to this day and Wangtu Bridge was not rebuilt for nearly two years. This make shift bridge is truck legal but one at a time alone and every gust sets the bridge swaying wildly and the truck then on the bridge goes with the flow. It’s a wild ride, adrenalin centric and very exciting to the brave. An hour up from Wangtu, we hit Karchham, at the confluence of the Baspa with the Satluj, and turning southeast, entered what is undoubtedly one of the prettiest valleys in the western Himalayas. The Baspa river rises bang on the Indo Tibetan border and flows over 95 km to its confluence at Karchham at 1830 m. Its resultant valley is inhabited up to Chitkul (3475 m) and it is possible to drive up that far. Turning up this valley, we slowly ascended through the thick forest along its gushing waters to as far as Sangla, stopping around every bend to capture another bit of it on celluloid. There is an idyllic quality to the Baspa valley, a quiet sense of solitude and restfulness, a kind of déjà vu of some long forgotten mystical experience. When we struck camp that night by the waters, we felt a kind of homecoming, to a kind of place we knew. Sangla is situated on the right bank of Baspa river, 17kms up from Karchham. There is a small Baring Nag temple here, a small monastery and a Tibetan Wood Carving center many tourists want to ‘do'. Sangla village is built on a stiff slope, the houses rising one behind the other in a picturesque stage set 14 type scene. We found our purpose in walking its meandering lane, peeping into the many courtyards and bylanes, absorbing the spirit that pervaded this simple place. Later in the afternoon, we opted to give our driving legs a break and walked up to Kamru village. Kamru is superlatively picturesque, sitting out on a flat ledge in a verdant sea of green, its wooden fort rising sentinel above the pagoda roofed settlement houses to watch over its inhabitants under the benign gaze of the Kinnar Kailash mountain. Kinnauri Rajas were traditionally crowned in this fort, and it now features a temple dedicated curiously to Kamakshi Devi. The Pujari had no explanation for this oddity, telling us only that the idol had been sourced from Gauhati. Our second night at Sangla was a stormy one, wind lashed and wet, and while we were reminded of the fickle faith of the gods, the day dawned clear and we set out the drive up to the road head of the valley at Chitkul. The higher stretches of the valley are even more dramatic in their beauty. We found cultivation throughout, the fields stretching to the very edge of the valley to meet the thick forests that spilled off the sheer slopes of these massive mountains. Chitkul is the very quintessence of Kinnauri reality, a small open village of stone built cottages, thinly populated by a handsome, simple, welcoming people. It sits high over the river, gazing placidly over the valley views to the east. There are 3 temples to the local goddess Mathi here, simple hill structures of faith, rather than flaunting egotism, the main one of which we were told was 500 years old. “Timelessness” here is not a touristy cliché: there is this intense feeling of something eternally still, eternally unchanged. Back at the camp, we were invited to go angling. India's first trout breeding farm was set up in Sangla way back in 1926. Besides April, October is the best time to angle for Brown and Rainbow Trout and we didn’t think we wanted to face the rushing June waters. There are saffron fields here as well, but we found our spot of solitude in slowing the pace, gazing up at the mountains and preparing for the journey ahead. Retracing our route back to Karchham the following morning, we then struck out northeast again, spanned Powari, once the favorite resting ground of Lord Dalhousie, then Recong Peo, Kinnaur's sub divisional headquarters, and turning west, ascended up the mountain to our next destination: Kalpa. Kalpa is a delightful destination in the Hill station genre, split between its close built old settlement part and 15 the more open, deodar nestling resort part. Chini Bazaar is Kalpa’s numero uno meandering destination, featuring quaint shops, copious shopping of the bric-a-brac type and all the local color that anyone would expect from a small Himalayan settlement. The 800-year-old wood built very Hindu temple of a quite unique indigenous design is Kalpa’s best-known monument. The pagoda roofed temple structures were almost entirely carved with simple motifs and painted in bright life affirming colors. There are scenes from the epics, images of deities, tantric symbols, animals, and so much of that joie de vivre that simplicity confers upon mankind. We sat out in the courtyard of the temple as afternoon gently tip toed away the day, gazing up at the holy 6050 meter snow clad Kinnar Kailash peak, the winter abode of lord Shiva, so close we thought we could reach out and touch it. Kalpa is a place to walk, hike, sip copious quantities of beverages in its many small garden restaurants and experience the silence of restfulness. On our last night at Kalpa, the moon was near full and we sat out after dinner to contemplate the holy peak. The cloud cover was surprisingly low for summer and we spotted a small stratocumulus formation about the peak changing shapes constantly. Somewhere in one frozen moment, it took on the form of a beckoning hand, its finger crooked. We stood amazed, rejecting the invitation, seeking shelter in cynicism, leaving the sublime issue swaying mesmerizingly atop Shiva’s abode. FACTFILE Narkanda The HPTDC run Hotel Hatu has been Narkanda’s residence of choice for twenty years now offering 16 double rooms for Rs. 1000/- in season. Mahamayan, down in the bazaar, now offers an alternative with 8 doubles for Rs. 600/- in season. Advance booking is desirable but not necessary as most tourists are day-trippers. Sarahan HPTDC’s Hotel Shrikhand facing the Shrikhand Mahadev peak offers 21 doubles for Rs. 3000/-and is generally booked out well in advance in season. All other options in Sarahan are of the guesthouse genre – Bashal, Sagarika and Snow View – and cost less than 500/- at the height of the season. Advance booking with HPTDC is essential. Sangla Although there are now three quality luxury camp operators in Sangla, Banjara Camps - the pioneers who started it off - remain the most popular and most expensive at Rs. 1400/- per head per person per day. The others are new, get spill traffic and will negotiate to under Rs. 1000/- per person per day. There are a half dozen guesthouses in town, all offering rooms under Rs. 300/- and not worth a look. Booking in advance is now unnecessary. 16 Kalpa: Kalpa offers four hotels in the Rs. 1000 range: Kinnar Kailash, Timberline, Blue Lotus and Kinner Villa. There are a half a dozen guesthouses too but at Rs. 200/- a room can only be used in a crises. Kalpa sees a lot of Kinnar Kailash parikrama traffic in summer so advance booking is probably desirable. 5. Initiative Our Workshop schedule Feb 2005 to May 2005 is set out below. Details at http://www.iallm.org/ 1. Understanding Joint Ventures: Structuring, Drafting, Negotiating and closing Win-Win Joint Ventures and shareholders agreements. 2. Understanding Asset and Business Buy outs: Structuring, Risk Assessing, Drafting. Negotiating and closing Asset Acquisitions. 3. Making Effective Business Partnerships: Structuring, Drafting, Negotiating and closing Win-Win Business Alliances 4. Winning Legal Wars: The Business Managers guide to Law, Litigation and Strategy -x- 17 February 12, 2005 March 12, 2005 April 16, 2005 May 14, 2005