Unit 31

advertisement

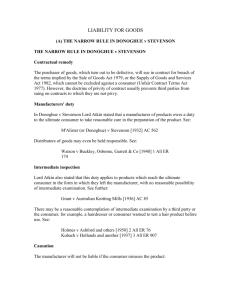

Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities UNIT 31 - MANUAL FOUR (A) PRODUCT LIABILITY/ (B) INTERENCE WITH CONTRACT & PASSING OFF 1 Claims under Donoghue v Stevenson Narrow Rule 2 Manufacturer - including repairers (Haseldine v Daw & Son Ltd [1941]), installers (Stennett v Hancock [1939]) & suppliers (Andrews v Hopkinson [1957]) - owes duty of care to ultimate consumer where (i) he intends products - virtually everything capable of causing damage - to reach consumer - anyone def should reasonably have contemplated to be injured by his neg - in form in which left him; (ii) no reasonable possibility of intermediate examination; & (iii) knows absence of reasonable care will result in consumer suffering injury/ damage but where manufacturers reasonably expect intermediate examination, could not foresee consumer suffering injury from Neg & not liab (Kubach v Hollands [1937]); Where 3rd party examination would not reveal defect (e.g. hidden), manufacturers remain liab & not part of claimant’s responsibility to show no prospect of intermediate examination – rather, important issue for court to consider in determining whether damage reasonably foreseeable; Duty objectively that of reasonable person & where such standard not met, manufacturer in breach & duty continuing – not cease once product has left manufacturer who must take all reasonable steps to ensure safety of consumers; Claimant must establish (i) dangerous defect present when product left manufacturer; (ii) caused by manufacturer’s carelessness/ neg; & (iii) def owed claimant duty of care but neg could not be presumed & res ipsa loquitor not apply although claimants not have to identify specific acts so where defect exists re construction/ manufacture, neg by manufacturer inferred but claimant has to show defect didn’t occur after product left manufacturer (Grant v Australian Knitting Mills Ltd [1935])& inference rebuttable by def if can show how defect incurred & that not due to his neg; Warnings prevent breach if adequate – clearly communicated & easy to understand & nature/ extent of danger made clear - but greater the danger, more explicit must warning be; Claimant must show causal link breach to loss on basis of ‘but for’ test but must eliminate other possible causes & inferences cannot be inferred where (i) defect may have been caused by other parties; (ii) those who supplied final product to consumer could have examined goods; or (iii) damage might have been due to other causes (Evans v Triplex Safety Glass Co Ltd [1936]) & where claimants aware of dangers yet chose to ignore them, unlikely manufacturer liab since, injury becomes self-inflicted – novus actus interveniens. Damages recoverable under Narrow Rule 3 Breach must result in recoverable damage which must be reasonably foreseeable (The Wagon Mound [1961]), embracing injuries/ damage to other property but, by Murphy v Brentwood D C [1990], damage to defective products themselves excluded because are PEL - premised on Donoghue being based on products dangerous but not merely defective so at tort consumer cannot recover repair/ replacement costs re product itself. Claims under Consumer Protection Act 1987 (CPA) Additional remedy to Narrow Rule &, by s.2(1) defs (set out in s.2(2)-(3)) liab whenever any damage caused wholly/ partly by defect - by s.2(1), requirement merely is to prove defect & not that def at fault or careless - in product – by s.1(2) = any goods or electricity including products comprised in other products such as Page 1 Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities 4 component parts - so claimant class wide & embraces buyers, product users & anyone else who suffers loss even if not foreseeable victim; Claimant must show defect/ loss causal link on ‘but for’ test basis &, by s.3(1), defect = product unsafe where safety not that which persons are generally entitled to expect (aka consumer expectation test), factors being (i) presentation (e.g. purposes for which product marketed, ‘get-up’ & trade mark); (ii) instructions/ warnings; (iii) reasonably expected use; & (iv) age (but defect not inferred merely because later product safer); By s.2(2)-(3) potential defs = (i) Producer (by s.1(2) manufacturer) including, where component part faulty, manufacturer of such part AND that of whole product; (ii) own brander – person puts own name/ trademark on product holding himself out as being producer; (iii) importer of products into EU from non-member state; & (iv) supplier (e.g. retailer ) if fails, on request, to provide claimant details of producer (=’forgetful’ supplier); By s.4 defences = (i) Defect attributable to legal requirements compliance (a); (ii) def did not supply to another (b) or supplied other than in course of business (c ); (iii) defect not exist when def supplied (d); & (iv) manufacturer of component parts not liab where defect in finished product attributable to finished product’s design or compliance with such product’s manufacturer’s instructions (f); Development risks defence (aka ‘state of the art) (e) = most controversial provision in CPA & provides defence where state of scientific/ technical knowledge at time of manufacture not such that producers of such product expected to have discovered defect if it then existed so def must show defect unknown/ unforeseeable when product distributed – that not neg in failing to discover & where known danger, producers continue production/ supply at their risk (A & others v National Blood Authority & another [2001]); S.7 prohibits limitation/ exclusion by contract terms, notice or otherwise &, by s.6(6) & Sch 1, actions must be commenced within 10 years from date product circulated by def. Types of CPA loss 5 Damage, by S.5(1)-(4), = death, PI & property (including land) loss/ damage but (i) damage to product itself excluded); & (ii) property must be that ordinarily intended for private use & actually intended mainly for claimant’s private use – so business property excluded - (s.5(3)), property value must exceed £275 (s.5(4)) & no specific provision that direct economic losses following damage/ injury (e.g. loss of income) recoverable but likely since damages assessed on standard tort principles. Evaluation of claims under Narrow Rule, CPA & Contract CPA liab relatively strict but in Neg def’s fault must be proved & property damage recoverable under both causes but CPA more restricted since business property & personal property < £275 excluded so where these damaged claimants better advised to seek action in neg rather than under CPA Complainant class wider under CPA as victim not need be foreseeable but potential def class narrower as repairers, installers not within ‘producer’ definition; Complainants should consider claims in contract unless neither buyer, not within provisions of Contracts (Rights of 3rd Parties) Act 1999 or supplier no longer exists since may be more beneficial due to implied satisfactory quality/ reasonably fit for purpose condition from s.14 SOGA which provides strict liab without proving fault exists & damages for all losses including replacing/ repairing defective product but, even then, damage to business property may be too remote under Hadley v Baxendale (1854) principle unless either (i) natural consequence of breach; or (ii) were in parties’ contemplation when contract made. Page 2 Objective Notes: W300 – Agreements, rights & responsibilities 6 Interference with subsisting contract 7 If, A, without lawful justification, intentionally interferes with contract between B & C & as result A (i) persuades C to break contract with B; or (ii) by A’s unlawful act he prevents C from performing the contract, B may claim against C in contract for his breach & A in tort for A’s intentional interfere (Lumley v Gye (1843-60)); Examples = (i) direct persuasion where A liab to B if A’s words to C intend (& do) cause C to break his contract with B; (ii) direct intervention where A’s conduct on B’s person/ property prevents B performing his contract with C, A is liab to C, provided A’s conduct unlawful; & (iii) indirect intervention where A, through 3rd party, causes a breach to B’s contract with C, A is liab to C, provided unlawful means used so to do A must know that contract between B & C exists – albeit A not need to be aware of contract’s details – so A not liab if not so aware & his interference is merely Neg & damage must be suffered by C, resulting from A’s interference so if breach would have occurred anyway, not result of interference & A not liab; Interference may be justifiable where, e.g., C, B’s employee, advised by A, his doctor, gives up work because of C’s ill health, then A is likely to be able to rely on justification of his ‘interference’ if B sues him but advancing one’s own interests does not constitute justification. Passing off A, pretending good’s are B’s, has committed passing off & liab to B, premised on it not being permitted for A to sell goods/ provide services under pretence that are B’s & occurs where trader, in course of trade, makes misrep to prospective/ ultimate consumers calculated to injure another trader’s business/ goodwill, provided such damage reasonably foreseeable consequence & actually caused so where tests met, def liab unless, on the facts, exceptional features exist which justify on public policy grounds withholding remedy from claimant (Erven Warnink BV v J Townend & Sons (Hull) Ltd [1979]; Passing off committed where def’s representation causes general public to confuse def’s goods/ business with claimants & calculated to deceive public, albeit claimants do not have to establish def acted dishonestly; Examples = (i) trade marks – copying/ imitating another’s registered trade mark; (ii) product ‘get-up’ as in containers etc strongly associated with specific product in public’s mind (Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc [1990]; & (iii) person can trade freely under own name even if injures another trader same or similar name but passing off may be found where def gives name/ description to products/ services where likely substantial purchasing public misled into believing person’s goods/ services are those of claimant. Page 3