St. Mary's College of Maryland

advertisement

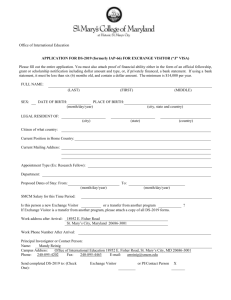

ST.MARY'S COLLEGE OF MARYLAND HANDBOOK FOR ENGLISH MAJORS 2006-2008 INTRODUCTION Why Become an English Major? In his classic work The Idea of a University, John Henry Newman describes liberal education as a precondition, like health, for all further study, citizenship, personal growth, and professional success, because it gives the student a critical perspective on self and world necessary to being an independent human being. The study of all languages and literatures is fundamental to such a perspective because language is the primary medium by which people respond to and make sense of their lives. In the English major, a student can engage in this study by analyzing and by creatively interacting with literatures written in English by people from a variety of cultures and historical eras. The major offers an opportunity to read works in which others have represented human experience, to craft one’s own writings, and to analyze the medium of language itself. The study of English language and literature not only provides language and thinking skills necessary in a climate of employment that demands verbal and cognitive versatility. It also introduces students to an interconnected tradition of authors, works and ideas, a community with which readers have interacted for hundreds of years to enrich their personal lives as well as to gain perspective on their vocational choices. Will I Do Well in English? The diversity of topics studied in English has long attracted liberal arts majors who love using as well as analyzing language and who want an inclusive, humanistic approach to liberal education. English classes often incorporate ideas, texts, and methods of many disciplines, from physics and biology to philosophy and psychology. But students coming out of high school should be aware that the kinds of great philosophical and moral questions they may only have encountered in their English classes are presented in many humanistic college disciplines--philosophy, history, foreign language and culture studies, art, music, and theater. Each of these disciplines does so from a unique point of departure; in the case of English, this point of departure is the aesthetic and communicational uses of the English language. If you choose to major in English, you should do so because, first and foremost, you have a fascination with language. Reading should be something you really like to spend time on, not a task to be finished as quickly as possible. If you are a person ideally suited to majoring in English, you are also curious about ideas, eras, and cultures other than your own, and you feel energized by the 1 challenge of broadening your own perspective and writings by considering other people's experiences. You should also enjoy writing your ideas, responses, and feelings in formal and informal language, whether in creative or analytical writing; this is a large part of what you will be doing in the major. You should be willing to risk analyzing, sharing, and revising your ideas in order to arrive at your own carefully considered conclusions and further questions. The only "wrong" way to read or think is to do so carelessly or passively. This means that you should want something more than obvious or easy answers, and be eager to dig as deeply as possible into texts of all kinds--poems, novels, stories, essays, films, plays, cultural artifacts, documents, and oral traditions--in order to develop and explore your responses to them. It also means that you have a responsibility to the precious and fragile community of intellectual activity in which you are participating. You are not just educating yourself; you are influencing those working around you by your attitudes and your contributions. Opportunities for serious, shared thinking and learning are an endangered species in contemporary culture, as recent SMC grads constantly tell us in their nostalgic emails. Be willing to participate, to risk your real thoughts and feelings, to help others, and in doing so to keep up a spirit of intellectual morale for every one of us. Finally, successful English majors are concerned to explore all kinds of related fields-history, philosophy, foreign languages and literatures, social sciences, psychology, art, music, theater, and natural sciences--that shed valuable light on the texts we read. There are an astonishing variety of approaches to literature and literary texts. This variety is well represented by the English faculty at St. Mary's; no matter how your interests develop, you will find someone here who can work with you. Brief faculty biographies included in this handbook will give you an idea of who does what. The diverse interests of the English faculty also insure that you will be exposed to the many assumptions and approaches that make literature so interesting. As an English major, you will most likely prefer some texts and approaches to others, but the range you will be exposed to will enrich and deepen your experience, no matter what your focus. You will never be bored. DIRECTORY FOR INFORMATION The secretaries in the Montgomery Hall Office (MH 45; x4225) may be able to help you with forms and information. For approving transfer of English courses toward the major from other schools, you need to consult with the department chair (Spring 2007=Robin Bates; F 2007-Spring 2008=Ruth Feingold; see contact information, below). For other information about the major consult with your English advisor (if you wish to be an English major get an English advisor ASAP) or with the department chair. Biographical descriptions of faculty members and their interests are on the English Department web site and will appear in the next edition of the handbook. 2 Offices, phone numbers, & emails of English faculty for 2006-2008 are as follows: Robin Bates--MH6; x4852 (rrbates@smcm.edu) Chair, Spring 2007 Katherine Chandler--MH10a; x4428 (krchandler@smcm.edu); on leave 2006-2007 Beth Charlebois-MH125; x2108 (echarlebois@smcm.edu); on leave 2007-2008 Ben Click--MH7; x4253 (baclick@smcm.edu) Jennifer Cognard-Black--MH102b; x4233 (jcognard@smcm.edu); on leave 2006-2007 Jeffrey Coleman--MH124; x4240 (jlcoleman@smcm.edu) Ruth Feingold--MH52; x2109 (rpfeingold@smcm.edu) Chair, Fall 2007-Spring 2010 Michael Glaser--MH122; x4239 (msglaser@smcm.edu) Jeffrey Hammond--MH125; x4241 (jahammond@smcm.edu); on leave 2007-2008 Brian O’Sullivan—MH50; X4242 (bposullivan@smcm.edu) Donna Richardson--MH102d; x4234 (riolama@netzero.com) Bruce Wilson--MH8; x4254 (bmwilson@smcm.edu) Christine Wooley--MH102c; x4441 (cawooley@smcm.edu) Visiting faculty for 2006-2007: Debbie Covey--MH10a; x4225 (dacovey@smcm.edu) Jennifer Fossell--MH10a; x4225 (jefossell@smcm.edu) Mary Larkin--MH102a; x4235 (mllarkin@smcm.edu) Karla Lowery--MH10a; x4225 (kjlowery@smcm.edu) Karen Lowry-- MH10a; x4225 (kklowry@smcm.edu) Stephen Messenger--MH10a; x4225 (sjmessenger@smcm.edu) Colby Nelson--MH123a; x4236 (cdnelson@smcm.edu) Karen Outen—MH102a; x2165 (keouten@smcm.edu) ******* FIRST STEPS FROM THE FIRST YEAR If you are a first-year student considering an English major— 1) Consult with your advisor in the English department before signing up for courses. If you don’t have an English advisor, consult with the chair or with another faculty member in the department. During your first semester, if you think you might be interested in majoring in English, make an appointment to talk with a faculty member in English. The department chair is also available to give you information and to discuss courses as well as other opportunities in the major. It is especially important for you to talk to someone early if you plan to pursue a double major, admission to the MAT program, study abroad, or any other program that will require early, careful course planning. 3 2) Take one of the three Literature in History courses (ENGL 281, 282, 283) as soon as possible. These three required courses are the “gateway” to the major, providing background important for all further courses, including writing courses. While ENGL 106 , Introduction to Literature, may be counted towards the major, it is not required, and is used more often by non-majors to fulfill their General College Distribution requirements. If you feel less prepared in the basics of close reading you may wish to begin with this course, but this is an individual decision. Other 200-level courses count as electives but are not required (and only 8 credits of lower-division electives—106, 230, and 270—may count toward the 44 required credits in the major). 3) Check out the English department website (www.smcm.edu/english). In addition to the information in this handbook, the site contains short biographies of faculty members, including their interests and the courses they teach; information on choosing and doing a St. Mary’s Project in English; and information on publications to which you as a student can contribute, including the journal Slackwater and the student literary journal, The Avatar. This site is particularly important for laying out the SMP process and for information on the courses being offered next semester (which usually appear on the site before the college Schedule of Classes comes out). When you decide to be an English major-1) Formally declare yourself an English major as soon as you decide you want to be one, and get an English advisor if you don't already have one.If you have an English advisor, all you need to do is e-mail Alan Lutton, at anlutton@smcm.edu, or call him at x4388 and say you are declaring your major. Even if you are only somewhat certain of your major, declare it as soon as you can. Not only will you be included on departmental mailing lists, but the number and variety of courses, even future decisions about hiring more professors, are determined largely by counting the number of declared majors. You will help everyone in the community of English majors by declaring as soon as possible. 2) You need an advisor in English to declare yourself an English major. If you don’t have one already, ask an English faculty member to send Alan Lutton an e-mail agreeing to be your advisor. Changes of advisor must be made several weeks prior to preregistration in order for your new advisor to be authorized. Be sure your new advisor sends an email to Alan, because the change won’t go through until he or she does. If you are a double major and have an advisor already in another discipline, make permanent arrangements for additional assistance every semester from someone on the English faculty. PLANNING YOUR ENGLISH CURRICULUM Plan your major rather than letting it plan you. There are many different directions in which your particular major can take you: toward literatures in English which comprehend a thousand years of time and many different emphases of culture, country, class, gender, and ethnicity; toward poetry, fiction, or other genres; toward focusing on your own creative writing; toward graduate school and literary theory; toward public 4 education as an English teacher; toward connections with history, philosophy, literatures in other languages, science, music, drama, art, or other disciplines. The English curriculum has a great many options, allowing you, as the existentialists put it, the agony of freedom and choice. You could fall into the abyss, by choice, or—worse—by choosing to avoid choice. Or you could specialize narrowly from the first day you arrive and never try what you don’t already know and like. To avoid either of these extremes, sit down with your advisor and plan a tentative two-year outline of your English courses. Work out some options for including and expanding what you want to do, as well as what you should do—by taking courses in other disciplines, by working out small-group or individual independent readings or studies, by internships and other off-campus opportunities, and by other take-charge as well as traditional pathways. Above all, remember two things: you get out of the major the challenges you take up and the work you put into it; and no major in a liberal-arts college is job training or a direct step into a particular job or profession. You should take whatever you love in your coursework, as long as it is challenging and diverse, so that you will get the benefits of a liberal arts education rather than just a piece of paper claiming you have them. You should see career preparation as a gradual, parallel process in which, by the end of your sophomore year, you have done such painless, exploratory, and uncommitted things as going for initial testing or information to the Career Office and examining options by informational interviews, externships, and summer jobs. If you want to write for a living, you can also get good things on your resume by tutoring, volunteering, and writing for such college organizations as the newspaper and the English Activity Board. General Advice: Begin the major early rather than overloading at the end. As you will discover, the writing and reading requirements for English courses are extensive. You can often expect to do thrice-weekly entries in a journal plus readings, papers, and exams. Novel courses require hundreds of pages of difficult reading a week. Papers require planning if not research and multiple significant revisions for success. Most important, enjoying as well as understanding literature requires allowing yourself time to savor and think about readings. So try to complete the Literature in History courses before your junior year, and take the Methods course before your senior year. Then you can complete the courses required for the major by scheduling an average of two English courses in each subsequent semester. Many years of experience have shown that taking any more than two courses per semester is a recipe for discomfort if not disaster (what one student described as “mental heartburn”). If you begin the major late in your academic career, plan out a course of study with your advisor as soon as possible. Another important reason for beginning early is that, if you don’t take a range of courses before the second semester of your junior year, you will have significantly restricted your potential options for doing a St. Mary’s Project. The more exposure you can get to the rich range of subjects in the major, the more choice and depth of background you’ll have in developing a project. 5 REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MAJOR: a minimum of 44 credit-hours (11 4-cr. courses or equivalent) of coursework, consisting of a 24-hour core and 20 hours of electives in English (ENGL courses). I. The core (a minimum of 24 credit-hours/6 4-credit courses or the equivalent; all courses offered every semester): a) Three Literature in History courses, 4 credits each. Students entering SMC before Fall 2006 (or transfer students entering on a catalogue before 2006-2007) must complete a minimum of two. Students entering SMC from Fall 2006 onward must complete all three courses . ENGL 281: Literature in History I: The Beginnings through the Renaissance ENGL 282: Literature in History II: The Rise of Anglo-American Literature, 1700-1900 ENGL 283: Literature in History III: Twentieth-Century Voices The above courses provide background for all subsequent courses in the major; they examine literature historically, primarily within English-speaking communities. They should ideally be completed before the end of the sophomore year and should be planned with an advisor to provide background for appropriate upper-level courses the student intends to take in related areas (e.g. 281 before Shakespeare or Early American Literature; 282 before Romantics or Victorians; etc.). Some upper-level courses, especially on the 400 level, will require as prerequisite a survey which covers the same era. b. ENGL 304: Methods of Literary Study (4 cr.). As background for work in all upper-level courses, especially the St. Mary’s Project, this course introduces various literary-critical approaches to studying literature, as well as practice in doing research in the field. Prerequisite: one survey course. Students should take this course after taking several other literature courses, either at the end of sophomore year or first semester of the junior year (at latest by the end of the junior year). c. Senior experience. One of the two following 8-credit options: i. ENGL 493/494: St. Mary’s Project (see description of the project on the English Website) ii. A 400-level English course, plus an additional 4 upper-division semester hours in English not used to satisfy any other requirement for the major. If you choose this option, plan ahead so that you have a choice of 400-level courses. I. Electives in the major. Students entering under the 2006 catalog or later must take at least 20 credit hours (five 4-credit courses or the equivalent) of which 12 hours (three 4-credit courses) must be at the upper (300-400) level. Students who entered on an earlier catalog must take at least 24 credit hours, of which at least 16 must be at the upper level. Course content will vary; topics will be announced the preceding semester (on the Smartnet Schedule of Classes, click on the “New, Revised, and Experimental Courses” link for detailed descriptions) . Multiple sections of a course number may be offered during the same semester. Any of these course numbers may be repeated for credit provided the content is significantly different. ENGL 106: Introduction to Literature ENGL 201: Advanced Composition ENGL 230: Literary Topics ENGL 270: Creative Writing ENGL 350: Studies in Language: Historical, Linguistic, and Rhetorical Contexts ENGL 380: Studies in World Literature ENGL 390: Topics in Literature ENGL 395: Topics in Writing ENGL 400: Topics in Genre ENGL 410: Studies in Authors ENGL 420: Studies in Theory 6 ENGL 355: Studies in British Literature ENGL 430: Special Topics in Literature ENGL 365: Studies in American Literature Elective coursework in the major may also include the following: Up to four credit hours of upper-division literature courses in a foreign language Guided Readings (ENGL 297, 397, 497) 1-2 credits each Independent Study (ENGL 299,399,499) 1-4 credits Off-Campus Internships (ENGL 398, 498) 4-16 credits, of which only 4 may count toward the major (see section on Internships for which kinds of projects may be counted) 7 Traditionally, students have been encouraged to do their internships in the spring of their junior year. Such students often return to college with a new sense of purpose and ideas for a St. Mary’s Project. Many have also done internships during the summer before their senior year. 8 Students do a written project in addition to their activities at the worksite. Of the 16 credits given for the internship (fewer in the summer), 4 credits may be applied toward the 44 in the English major and the rest will count as general college electives. All internship projects, in every discipline, involve writing. The difference is that the projects receiving English credit involve either performing or analyzing professional writing (e.g. fictional writing, journalism, etc.) Sample projects include the following: A study of the role newspapers play in small towns (internship with a newspaper); A study of legislative positions and social science studies on pornography (internship w/ women’s lobbying group); A feature article on women and abuse (internship w/radio station); A feature article on a being a college intern reporter (with The Associated Press); A study of how city magazines promote their cities (w/ city magazine); A study of historical novels dealing with Maryland (w/ St. Mary’s Historical Commission) To find out more about the logistics of setting up an internship, go to the Career Center http://www.smcm.edu/careercenter/index.cfm?fuseaction=content.internships&ID=568. Study Abroad For over 25 years, SMC students, particularly English majors, have benefited from a special relationship with the Oxford Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. If you are interested in spending a semester or more in England at the Centre, follow this link for more information: http://www.smcm.edu/oxford For other programs in study abroad: https://www.smcm.edu/admissions/pdfs/StudyAbroad.pdf. 9 Two-Year English Schedule of English Courses, Fall 2007-Spring 2009 (Note: This rotation is tentative, especially for 2008-09, and may be subject to change) FALL 07 (On sabbatical: Beth Charlebois, Jeff Hammond) 201: Advanced Composition: Writing about Literature (Richardson) 230: Literary Topics: African American Expression (Coleman, Taylor) 230: Literary Topics: American Literature of the 1980’s (Stanton) 270: Creative Writing (Glaser) 270: Creative Writing (Outen) 281: Literature in History I (Wilson) 281: Literature in History I (Bates) 282: Literature in History II (Cognard-Black) 282: Literature in History II (Wooley) 283: Literature in History III (Coleman) 283: Literature in History III (Feingold) 304: Methods of Literary Study (Wooley) 355: Studies in British Literature: The Romantics (Richardson) 355: Studies in British Literature: Shakespeare (Ellis-Tolaydo) 365: Studies in American Literature: Harlem Renaissance (Nelson) 380: Studies in World Literature: Asian Literature (Wilson) 390: Topics in Literature: Books that Cook (Cognard-Black) 390: Topics in Literature: Film Genres (Bates) 395: Topics in Writing: Nature Writing (Chandler) 395: Topics in Writing: Advanced Poetry (Coleman) 395: Topics in Writing: Advanced Fiction (Outen) 400: Studies in Genre: Parody (O’Sullivan) 420: Studies in Theory: Rhetoric and Poetics (Click) 430: Special Topics in Literature: AngloIndia/IndoAnglia (Feingold) SPRING 08 (On sabbatical: Beth Charlebois, Jeff Hammond) 201: Advanced Composition: Argumentative Writing (Click) 230: Slave Narratives (Wooley) 230: Mysteries of Identity (Wooley) 270: Creative Writing (Glaser) 270: Creative Writing (Glaser) 270: Creative Writing (Outen) 281: Literature in History I (Bates) 281: Literature in History I (Wilson) 282: Literature in History II (Richardson) 282: Literature in History II (Chandler) 283: Literature in History III (Coleman) 304: Methods of Literary Study (Wooley) 355: Emerging Novel (Chandler) 355: Cool Brittania (Feingold) 365: Alienation in American Lit (Coleman) 365: Contemporary American Poetry (Stanton) 380: Tale of Genji (Wilson) 380: Tolstoy’s War and Peace (Richardson) 390: Topics in Literature: American Comedy (Click) 395: Topics in Writing: Fiction (Cognard-Black) 395: Topics in Writing: Creative Nonfiction (Outen) 395: Peer Tutoring (O’Sullivan) 400: Crossing the Color Line (Wooley) 410: Wright, Ellison, Baldwin (Nelson) 10 Fall 2008 (On sabbatical: Robin Bates, Donna Richardson) 201: Advanced Composition (multiple sections possible) 230: Shakespeare, Sex, and Gender (Charlebois) 230: Science Fiction (Nelson) 270: Creative Writing (multiple sections) 281: Literature in History I (Charlebois, Wilson) 282: Literature in History II (two of the following: Cognard-Black, Chandler, Wooley) 283: Literature in History III (two of the following: Feingold, Coleman, O’Sullivan, Staff) 304: Methods of Literary Study 350: Rhetoric of Politics (O’Sullivan) 355: Shakespeare (Charlebois) 355: The Victorians in Text, Photo and Film (Cognard-Black) 365: American Gothic (Wooley) 365: Literature and Music as Social Protest (Coleman) 390: Landscape and Literature (Chandler) 395: Creative Non-Fiction (Hammond) 395: Topics in Writing (Staff) 395: Topics in Writing (Staff) 400: Female Coming of Age Novel (Feingold) 410: Dante (Wilson) 420: Modern Rhetorical Theory (Click) Spring 2009 (On sabbatical: Robin Bates, Donna Richardson) 201: Advanced Composition 230: American Plays and Playwrights (Charlebois) 270: Creative Writing (multiple sections) 281: Literature in History I (Charlebois, Wilson) 282: Literature in History II (two of the following: Cognard-Black, Chandler, Wooley) 283: Literature in History III (two of the following: Feingold, Coleman, O’Sullivan, Staff) 304: Methods of Literary Study 350: Peer Tutoring (O’Sullivan) 365: Realism and Modernism in American Lit (Nelson) 365: Sympathy and Sentiment (Wooley) 365: Multicultural Literature (Coleman) 380: New Testament Narrative (Hammond) 380: Post-Colonial Lit (Feingold) 380: Modernism and the Noh (Wilson) 390: Woman Word (Cognard-Black) 390: Environmental Literature (Chandler) 395: Advanced Poetry (Coleman) 395: Topics in Writing (Staff) 410: Mark Twain (Click) 410: Staging Shakespeare (Charlebois) 11