BSB51407 PM Diploma

advertisement

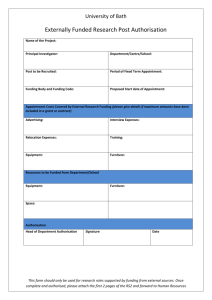

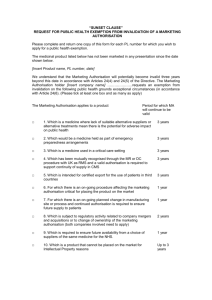

BSB51407 - Diploma of Project Management Project Scope Management Questions & Answers Plus Exercises Page |2 Table of Contents Table of Contents........................................................................................................................ 2 Questions for Scope Management .................................................................................................... 3 Answers for Scope Management ....................................................................................................... 7 Exercises - Manage Project Scope ................................................................................................ 8 Responsibilities for project scope activities ................................................................................... 8 Stakeholder involvement in project scoping ..................................................................................... 8 Reflection: Scoping a project......................................................................................................... 8 Conduct project authorisation ........................................................................................................... 9 Defining the scope of a project ........................................................................................................ 12 Reflection: Breaking deliverables into manageable chunks ....................................................... 12 Reflection: Conducting a Works Breakdown exercise ................................................................ 13 Clarifying outcomes and establishing performance measures ........................................................ 14 Reflection: Developing a performance review plan .................................................................... 14 Reflection: Improving scope management - Sydney Opera House project ................................ 15 Reflection: Assessing scope effectiveness and recommending changes .................................... 17 Page |3 Questions for Scope Management 1. Of the following, which is not part of project scope management? a. Scope planning b. Scope verification c. Quality assurance d. Create WBS 2. You are the project manager for the HGD Project and will need as many inputs to the scope planning as possible. Of the following, which one is not an organizational process asset? a. Organisational procedures b. Organisational policies c. WBS d. Historical information 3. You are a project manager for your organisation. Sarah, a project manager in training, wants to know which project documents can stem from templates. Your answer should be? a. Risk policies b. Organisational policies c. Scope management plans d. Historical information. 4. You are the project manager for a technical project. The project product is the complete installation of a new operating system on 4500 workstations. You have, in your project cost and time estimates, told the customer that the estimates provided will be accurate if the workstations meet the hardware requirements of the new operating system. This is an example of which of the following? Page |4 a. Risk b. Assumption c. Constraint d. Order of magnitude 5. You are the project manager for the NBG Project. This project must be completed within six months. This is an example of which of the following? a. Schedule b. Assumption c. Constraint d. Planning process 6. Which of the following best describes the project scope statement? a. The description of the project deliverables. b. The authorising document that allows the project manager to move forward with the project and to assign resources to the tasks. c. A project scope statement focuses on completing all of the required work, and only the required work, to create the project’s deliverables. d. The process of planning and executing all of the required work in order to deliver the project to the customer. 7. During the planning phase of your project, your project team has discovered another method to complete a portion of the project scope. This method is safer for the project team, but may cost more for the customer. This is an example of: a. Risk assessment b. Alternative identification Page |5 c. Alternative selection d. Product analysis 8. Of the following, which does the scope statement not provide? a. Project justification b. Project product c. Project manager authority d. Project objective 9. You are the project manager for the JKL Project. This project has over 45 key stakeholders and will span the globe when implemented. Management has deemed that the project’s completion should not cost more than $34 million. Because of the global concerns, the final budget must be in U.S. dollars. This is an example of which of the following? a. Internationalisation b. Budget constraint c. Management constraint d. Hard logic 10. You are the project manager for your organisation. You need to ensure the customer formally accepts the deliverables of each project phase. This process is known as ______________________? a. Earned value management b. Scope verification c. Quality control d. Quality assurance Page |6 Page |7 Answers for Scope Management 1. c) Quality Assurance is not part of project scope management. It is the quality assurance program of the entire organisation. 2. c) The WBS is not an organisational process asset. 3. c) Scope management plans can be based on templates. For the record, so can the WBS, and project scope change control forms. 4. b) This is an example of an assumption since the workstations must meet the hardware requirements. 5. c) A project that must be completed by a deadline is dealing with time constraints. 6. c) A project scope statement focuses on completing all of the required work, and only the required work, to create the project’s deliverables. 7. b) Alternative identification is a planning process to find alternatives to completing the project scope. 8. c) It is the project charter that provides the project manager with authority. 9. b) This is an example of a budget constraint. The budget must not exceed $34 million. In addition, the metric for the values to be in U.S. dollars can affect the budget if most of the product is to be purchased in a foreign country. 10. b) Scope verification is the process of formally accepting the deliverable of a project or phase. Page |8 Exercises - Manage Project Scope Responsibilities for project scope activities Personnel Responsibility Project manager Leads the project team in defining and managing the scope of the project, including refining the scope progressively throughout the project, monitoring scope, identifying ‘scope creep’ and monitoring and reporting to higher authorities on changes Authorising agent/agency Selects and briefs the project manager, authorising the project and endorsing the scope management plan, receiving and analysing review reports and meeting with the project manager at agreed critical points during the project. The authorising agent may also be required to step in, in the case of a crisis in the project, or in a dispute resolution role. Project team member(s) Contribute to the scope definition process including the development of the scope management plan; work as a team under the leadership of the project manager to apply the project scope controls; participate in project review and evaluation activities Stakeholder involvement in project scoping Reflection: Scoping a project Case Study 2: Training Program Development provides details of a Request for Tender (RFT) to produce a program and resources for the Training of Customer Service Officers in a local police force. Reflect on the scenario below, considering whether to respond to the request for tender. The unit you manage is quite small – just yourself as manager, three full time content development specialists/writers and one administrator. The unit designs and publishes learning materials and draws on the services of consultant instructional designers, editors and graphic artists as required. In reviewing the RFT you note that the timelines are very tight (only three months to write and produce 400 hours of teaching material). You know that you have the expertise to develop the curriculum and assume that because the Training Program is similar to one that the unit already delivers that you will be able to customise some existing materials. You note also that the materials produced by the project will be owned by the contracting organisation and that you will need to carefully document your existing intellectual property so that the materials already produced by the Page |9 unit for use in teaching will remain the property of the college. You realise that you will need to source two teachers for a month each to help prepare the materials and that you will need the head of school to agree in principle to the temporary transfers of two teachers to you. As you only have one week to write the proposal and will need to put aside some other work for this time, you decide that you need to talk over the options with the head of school. As a basis for that meeting you need to prepare a briefing note including details on the following: 1. The outcomes of the project – for the Unit and the School. 2. The project deliverables. 3. The resources you will need from the school to complete the project. 4. The risks associated with proceeding or not proceeding. Conduct project authorisation Before proceeding, find out about the project authorisation procedures in your own workplace, and answer the questions in the tables below. Project authorisation in your organisation Name of organisation Name and position of my project authorising officer Is there a document that outlines the authorisation procedure? At what stage(s) does authorisation need to be secured? Is there a proforma/template to use? The checklist in the following Authorisation Checklist table identifies standard items that may be addressed in a project authorisation process. Use the checklist to compare your own organisation’s authorisation procedures with these standards. How does your organisation compare? Are there items that are not addressed? If so find out why. Are there additional items included in your own authorisation processes? If so add these items. P a g e | 10 Authorisation checklist table Standard item Explanation/definition Project name and number Used to identify and classify the project Project sponsor Person/company who has contracted the project Project manager The person leading the project team who is responsible for project outcomes Project director The person to whom the project manager reports Priority ranking Urgency in relation to other projects Problem/opportunity What led to the project being commissioned Deliverable Specific outcome(s) Key objectives Major commitments/ work to be achieved Critical success factors Indicators that the outcome has been achieved Stakeholders People who have a stake/ interest in the project and can influence its success Performance reporting A statement of how progress will be measured and communicated Specification Describes the deliverables in detail Budget & resources The funding and other resources (including people, space, equipment) required to achieve project outcomes on time Time Start and finish dates; critical milestones Risks, obstacles, assumptions What might go wrong or get in the way; assumptions on which the specification, budget and timelines are based on Escalation management Strategies for managing issues, conflict and disputes Contingency Backup strategies – part of risk management Used in my workplace () P a g e | 11 Standard item Explanation/definition Contractual arrangements Between project sponsor and project organisation; between project organisation and sub-contractors Business value Rationale for taking on the project Approvals Sign-off required for project to commence and proceed Attachments Any document accompanying the authorisation proforma Prepared by/ Date Person submitting the authorisation Approved by/Date Person(s) authorising the project/approving the scope Used in my workplace () P a g e | 12 Defining the scope of a project Reflection: Breaking deliverables into manageable chunks First read Case Study 1 about Perfect Pergolas and list all of the project tasks that are mentioned in the story. Then take the 5 subtasks listed below and break each down into smaller components. Once you have divided the sub-tasks into sub-sub-tasks, ask yourself whether these components are small enough to be manageable. If so, list the sub-sub-tasks in the order in which they will need to be completed. Use the table below to format the tasks and sub-tasks. The first set of sub-tasks have been completed as a guide Perfect Pergolas: JOB NO: 129: MR ARCHIBALD COMMENCEMENT DATE: 4 APRIL 2009 WORK PLAN Planning and permits Finalise building design and specifications and get client sign-off Apply for permits to clear and build Develop 1st draft master schedule Source and price materials Finding and contracting suitable subcontractors Email/phone three sets of sub-contractors with offer; 24 hour turn-around on acceptance Develop sub-contracting schedule and contract; organising signing Lock construction team into schedule Revise and distribute master schedule to sub-contractors and team Preparing the site for construction Undertaking the construction in compliance with building regulations Making good – including rubbish removal and handover P a g e | 13 Reflection: Conducting a Works Breakdown exercise In the Case Study of Training Program Development breaking down all the tasks to be done to the level of detail required will ensure that adherence to timelines and budgets can be monitored. This breakdown will become an attachment to the contract. To develop the breakdown, first list all of the project management activities, for example: Get content of each component agreed; Source lists of probable attendees, find out leave schedules, develop training schedule etc. Once you have listed all work activities, put them in order and plot them against the timeline for the project, and also identify the cost items for each stage. (For the purposes of this activity the budget should include all cost items but actual costs are not necessary). Once you have allocated each activity to a time line and budget item, ask yourself if the breakdown of tasks is sufficient to be able to accurately cost the activity and identify time and budget blow-outs P a g e | 14 Clarifying outcomes and establishing performance measures Reflection: Developing a performance review plan To develop a plan to review progress on the pergola construction, you should include details of what is being reviewed, when the review will take place and how it will be conducted. You may decide to present the plan in tabular form, using the sample layout below. Work Plan Work task Progress Review Plan Scheduled Completion Scheduled review Conducted by: Method Actual completion P a g e | 15 Reflection: Improving scope management - Sydney Opera House project Read the extract below on the design and construction of the Sydney Opera House and develop an initial scope statement that would cover objectives and deliverables. Identify and classify all of the changes that took place and map these against the original scope of the project. The construction of Sydney House- an example of scope creep The Bennelong Point Tram Depot, present on the site at the time, was demolished in 1958, and formal construction of the Opera House began in March, 1959. The project was built in three stages. Stage I (1959-1963) consisted of building the upper podium. Stage II (1963-1967) was the construction of the outer shells. Stage III consisted of the interior design and construction (1967-73). Stage I was called for tender on December 5, 1958, and worked commenced on the podium on May 5, 1959 by the firm of Civil & Civic. The government had pushed for work to begin so early because they were afraid funding, or public opinion, might turn against them. However major structural issues still plagued the design (most notably the sails, which were still parabolic at the time). By January 23, 1961, work was running 47 weeks behind, mainly due to unexpected difficulties (wet weather, unexpected difficulty diverting stormwater, construction beginning before proper engineering drawings had been prepared, changes of original contract documents). Work on the podium was finally completed on August 31, 1962. Stage II, the shells were originally designed as a series of parabolas, however engineers Ove Arup and partners had not been able to find an acceptable solution to constructing them. In mid 1961 Utzon handed the engineers his solution to the problem, the shells all being created as ribs from a sphere of the same radius. This not only satisfied the engineers, and cut down the project time drastically from what it could have been (it also allowed the roof tiles to be prefabricated in sheets on the ground, instead of being stuck on individually in mid-air), but also created the wonderful shapes so instantly recognisable today. Ove Arup and partners supervised the construction of the shells, estimating on April 6, 1962 that it would be completed between August 1964, and March 1965. By the end of 1965, the estimated finish for stage II was July 1967. Stage III, the interiors, started with Utzon moving his entire office to Sydney in February 1963. However, there was a change of government in 1965, and the new Askin government declared that the project was now under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Public Works. In October 1965, Utzon gave the Minister for Public Works, Davis Hughes, a schedule setting out the completion dates of parts of his work for stage III. Significantly, Hughes withheld permission for the construction of plywood prototypes for the interiors (Utzon was at this time working closely with Ralph Symonds, an inventive and progressive manufacturer of plywood, based in Sydney). This eventually forced Utzon to leave the project on February 28th, 1966. He said that Hughes’s refusal to pay Utzon any fees and the lack of collaboration caused his resignation, and later famously described the situation as "Malice in Blunderland". In March 1966, Hughes offered him a reduced role as 'design architect', under a panel of executive architects, without any supervisory powers over the House's P a g e | 16 construction but Utzon rejected this. The cost of the project, even in October of that year, was still only $22.9 million, less than a quarter of the final cost. The second stage of construction was still in process when Utzon was forced to resign. His position was largely taken over by Peter Hall, who became largely responsible for the interior design. Other persons appointed that same year to replace Utzon were E. H. Farmer as government architect, D. S. Littlemore and Lionel Todd. The four significant changes to the design since Utzon left were: The cladding to the podium and the paving (the podium was originally not to be clad down to the water, but left open. Also the paving chosen was different from what Utzon would have chosen) The construction of the glass walls (Utzon was planning to use a system of prefabricated plywood mullions, and although eventually a quite inventive system was created to deal with the glass, it is different from Utzon's design) Use of the halls (The major hall which was originally to be a multipurpose opera/concert hall, became solely a concert hall. The minor hall, originally for stage productions only, had the added function of opera to deal with. Two more theatres were also added. This completely changed the layout of the interiors, where the stage machinery, already designed and fitted inside the major hall, was pulled out and largely thrown away) The interior designs (Utzon's plywood corridor designs, and his acoustic and seating designs for the interior of both halls, were scrapped completely.) The opera house was formally completed in 1973, to a bill of $102 million. The original cost estimate in 1957 was £3,500,000 ($7 million). The original completion date set by the government was January 26, 1963. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sydney_Opera_House#Utzon_and_the_constructio n_of_the_Opera_House P a g e | 17 Reflection: Assessing scope effectiveness and recommending changes Read Case study 1: Perfect Pergolas and then read the story below about what happened when he secured the contract. 1 How effective was Kevin’s scope change management early in the project when Mr Archibald asked for a larger pergola? 2 What might you have done differently? Make recommendations regarding his scope change management strategy Perfect Pergolas: Plans and Realities Mr. Archibald was very impressed with Kevin’s tender to build the pergola. Kevin had managed to offer superior quality building materials and construction to heavy-weather construction standards, for just $5,000 above Mr Archibald’s optimum price. Further, Kevin had guaranteed completion three weeks after Council approvals were through. The contract was signed and Kevin immediately set to work on finalising the design to Mr Archibald’s specification. When the design was submitted for approval, Mr Archibald asked if the size of the pergola could be increased to facilitate some storage. Kevin agreed on the spot, subject to a small adjustment to costs. Having already checked with his suppliers he was confident that he could get the larger size pergola frame. While he was waiting for the permits to come back Kevin organised for the surveyor to check the local rules and also checked for underground cables in the excavation area. All went well with the initial planning: the permits arrived; the larger pergola was available, and the excavation was completed on time. When the formwork was in place, Kevin organised for a Council inspection, and also booked the concrete truck and organised the pergola delivery date, confident that the council inspection was a formality. The inspector contacted Kevin from the site to check the dimensions of the pergola, and on hearing Kevin’s response, queried the specifications for the concrete pour. He said that he did not think there was a problem, but as the pergola was way above the norm in the area, he would have to double-check the regulations. Shouldn’t take more than 48 hours to clear and he’d get back to Kevin by Friday. But that was the day for the concrete pour! Kevin cursed that he hadn’t double-checked the regulations himself: he was sure that the additional size was still in the same tolerance zone, but he didn’t have any paperwork to prove it. He’d just have to fit in with the inspector’s timetable, as he didn’t want to get the inspector off-side, or the site would never pass the inspection!