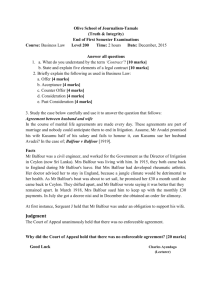

Domestic arrangements within the law

advertisement

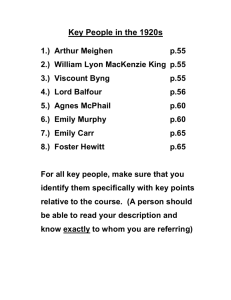

+ Balfour v Balfour Use the following to practise your paraphrasing skills: Step 1: Understand what you are reading. If you don't understand it, you can't paraphrase it correctly. That's guaranteed. Step 2: Think about the ideas, especially how the ideas may relate to your specific topic. Step 3: Not looking at the original, write down the ideas. Step 4: Look back at the original to see if you have changed the grammar and vocabulary. If not, change them now. Contract Law “Domestic arrangements within the law of contract: A feminist examination of Balfour v Balfour” Antony Lias, LLB student, Birkbeck College, London University. September 2004. ORIGINAL PARAGRAPH PARAPHRASE Contract law seeks to uphold the primacy of the individual whilst perpetuating the fiction that strangers meeting in the market place to exchange commodities are of equal bargaining strength. It has become a metaphor for economic liberalism, freedom and equality, and yet it is Balfour v Balfour which provides one of the starkest examples of individual subjugation and gender inequality. Throughout this paper, the argument will be advanced that married women have been denied the capacity to create an enforceable contract within a “domestic arrangement”, due to the doctrinal prominence of Balfour v Balfour and the inherent bias that exists within contract law as a whole This problematic case is centred on the enforceability of a “domestic” agreement between a husband and wife, and the requirement that there should be an intention to create legal relations. Here the husband agreed to pay his wife a monthly allowance whilst he was working away in Ceylon. Shortly after arriving in Ceylon the husband informed his wife that it would be better if they separated permanently. The wife therefore sought to enforce this agreement in contract. Although successful at first instance, it would be the Court of Appeal, and in particular the judgement of Lord Atkin, which would not only reverse that decision, but in so doing establish an additional test of enforceability that was both unnecessary and particularly damaging to the development of equal rights for women within the field of contract law. Lord Atkin was of the opinion that “agreements such as these are outside the realm of contracts altogether”, (1919 2 KB at 579) and that “one of the most usual forms of agreement which does not constitute a contract appears to me to be the arrangements which are made between husband and wife”. (1919 2 KB at 578) Lord Atkin then justifies his decision on two grounds. The first is a composite lack of intention in domestic agreements: “..they are not contracts because the parties did not intend that they should be attended by legal consequences”, (1919 2 KB at 579) whilst the second is an overt policy consideration requiring that the “floodgates” remain closed to such cases: It would be of the worst possible example to hold that agreements such as this resulted in obligations which could be enforced in the Courts…the Small Courts of this country would have to be multiplied one hundredfold if these arrangements were held to result in legal obligations. (1919 2 KB at 579) Before offering a feminist deconstruction of the above -“ two points, it is necessary to understand the ideational and substantive conceptions of women within contract law, and how it provides a backdrop for denying married women the equality afforded to men. We see contract being viewed as the “paradigm of free agreement”, (Pateman., 1993 p.59) ascribing to human beings the necessary attributes to fulfil the move from a status orientated position to one of endowed freedom and equality within civil society. However, Pateman argues that contract law is a method by which patriarchal values are affirmed, and women thereby subjected; it is intrinsically biased. A clear example of the overt masculinity of the law can be evidenced through the loss of a woman’s individuality upon entering marriage. (Supra 1986 p 35) The role of married women assigned by the law in _ 1919 was that of dependents placed “in the same category with criminals, lunatics, and minors as being legally incompetent and irresponsible.” (Supra 1986 p 35) Women essentially moved as chattels from one status relationship to another, namely from the father to the husband. Aside from various restrictions on the contractual capabilities of married women, the decision reached in Balfour v Balfour appears to reflect the dominant patriarchal values of the time. Within the marriage arena, the wife is denied the capacity to enter into a contract with, the husband, yet the capacity to enter into the marriage contract is unquestionably present. The paradox is all too clear; women both lack and possess the capacity to enter into contracts. One explanation provided is that upon entering marriage, women revert back to a status relationship, thereby leaving civil society for the “state of nature”. It is however Peter Goodrich who provides the most incisive account for such an existent state of affairs, by simply stating that “..the wife lacks contractual capacity because her will is not her own, but that of her masculine partner.” (Goodrich 1996 p 26), The Courts have reaffirmed the homosocial (Supra 1986 p 22) endeavours of a masculine dominated society by failing to address the obvious inequities presented in cases such as Balfour v Balfour, thereby simultaneously ascribing women an inferior status in civil society. The role of intention to create legal relations within such a context is clearly a veil for certain policy decisions, namely “..to keep contract in its place; to keep it in the commercial sphere and out of domestic cases.”(Hedley, 1985 p 391-415) Intention becomes here a very attractive proposition for “the courts to cloak policy decisions in the mantle of private contractual autonomy.”( Hepple, 1970 p28) This may explain judicial reluctance to intervene save in cases where there has been detrimental reliance, but it does nothing to redress the fundamental imbalance in power in such relationships. However, it is encouraging to note that in Pettitt v Pettitt, (1969 2 WLR 966) an indication was expressed that the ruling in Balfour may be limited in application due to it being an “extreme case” (1969 2 WLR 983) which “stretched the doctrine [that in ordinary day-today life spouses do not intend to contract] to its limits.” (1969 2 WLR 992) Whilst in Merritt v Merritt (19701 WLR 1211) the courts have accepted the validity of domestic agreements when one side has already performed their side of the bargain. The strongest precedent established for judicial encroachment into the private sphere, can be found in the case of R v R (1991 4 ALL ER 481). Here the ruling declared that the husband’s sexual access to his wife was not absolute, and that rape within marriage is now a criminal offence. Lord Keith added that: …the common law, however, is capable of evolving in the light of changing social, economic and cultural developments. Hale’s proposition [on the marriage contract] reflected the state of affairs in these respects at the time it was enunciated. Since then, the status of women, and in particularly of married women, has changed out of all recognition in various ways… marriage is in modern times regarded as a partnership of equals. (1991 4 ALL ER 481 ) R v R represents the logical deduction that if a wife _can either reject or consent to sexual contact within the marital relationship, she is also capable of entering into civil contracts. The ability to determine one's own response to such an offer is indicative of capacity. It is, however, a House of Lords ruling in a future case which is needed to either uphold or abrogate the presumption maintained in Balfour v Balfour that there is no intention present in such agreements, and to thereby assist in gender neutralising this particular body of law and its concomitant masculine bias. The decision in this case is indeed regrettable, because it propagates discrimination based on gender. The raison d’etre for its existence is not to ensure that intention is always present, but to avoid making serious policy decisions, which would entail exploring the masculine bias of contractarian thought. .