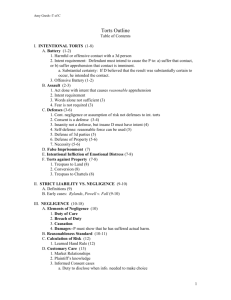

torts - eaton - spring 2004

advertisement