Practice in the Art of Contribution, PBL2: PBL (Problem Base

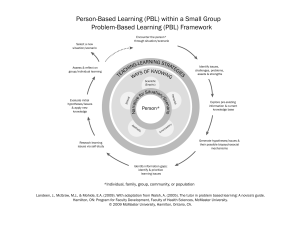

advertisement

Practice in the Art of Contribution: An Exploration of ProblemBased Learning (PBL) Part I: Introduction and Rational: The North Carolina State Board of Education policy, HSP-F-016 defining academic rigor, mandates that all students will graduate from a rigorous, relevant academic program that equips them with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary to succeed in both post-secondary educational performance and 21st Century careers and to be participating, engaged citizens. Academic rigor is based on expectations established for students and staff that ensure that students demonstrate a thorough, in-depth mastery of challenging and complex curricular concepts. In every subject, at every grade level, instruction and learning must include commitment to a knowledge core and the application of that knowledge core to solve complex real-world problems. To ensure academic rigor and relevance and to nurture supportive relationships for each student in the public school setting: Students must: Demonstrate content mastery and application of appropriate skills and critical thinking Become engaged learners who actively and responsibly participate in the learning process Raise questions, solve problems, think, reason, and reflect Complete rigorous, relevant high-level assignments in every subject Demonstrate learning through portfolios, exhibitions, service-learning projects, and senior projects that use state standards for evaluation Communicate effectively and appropriately for a variety of purposes Understand their own learning styles and strengthen their own affinities (http://sbepolicy.dpi.state.nc.us/ HSP-F-016) Problem Based Learning (PBL) This is not to be confused with Product Based Learning. The primary difference in these two approaches, according to Torp and Sage, is that in PBL the main “product” is a solution to the problem. In Project Based Learning, the main “product” is a culminating physical project (Torp and Sage, Problems and Possibilites) II. Problem Based Learning Background The primary model for this Demo is based on work by Dr. Ann Lambros of Wake Forest University. In her text, Problem Based Learning, (She has published 3 texts on PBL at are brief and concise, PBL for Elementary, PBL for Middle, and PBL for High School) she provides details and instruction on the implementation and use of Problem Based Learning. According to Lambros: PBL is a teaching method based on the principle of using problems as the starting point for the acquisition of new knowledge. (Lambros, 1) In order for teachers to utilize PBL, the following should be considered: Pivotal to its effectiveness is the use of problems that create learning through new experience, new content acquisition, and the reinforcement of existing knowledge. Each learner has his or her own real-world frame of reference that should be attended to when PBL problem scenarios are developed. It is essential that learners determine their own learning needs, or learning issues, based on the problem they encounter. Problem today: educators typically spend lots of time telling learners what they need to k now without first determining what they already know or what they think they need to know. Today, we provide students with information we have already deemed relevant thorough lectures, handouts, worksheets or assigned reading. In PBL the process is somewhat reversed. Through the problem, students decide what is relevant, make that declaration, and then seek out the info they need. The inexperienced PBL teacher may ask, “How do I know that students will come up with the appropriate issues, or how can I be certain that the intended content areas will be included?” Dr. Lambros’ answer is firm and unyielding: “Well constructed problems coupled with effective facilitation will prompt students into the intended learning areas” By nature, many instructors feel the need to force students into learning directions. To this type of teacher, PBL can be frightening because the ball is in the students’ court. Yet other teachers may assert that, “The test scores are the most important thing and this won’t work with courses that have a standardized test! Again, Lambros asserts, “The reality is that students’ scores go up when they know, understand, can retrieve information and use it in situations similar to those in which it was learned” (55). Socratic Seminars/Paideia Philosophy I utilize and encourage using the complete Paideia model of instruction (didactic instruction, coaching, and Socratic seminars) as the framework for your PBL problem(s) is an excellent way to organize and deliver the content in PBL. The three column structure is a custom fit for this style of teaching and learning, and this unit is designed with this philosophy in mind. According to Terry Roberts, Director of the National Paideia Center in Chapel Hill, PBL and the Paideia Coached project are a perfect mesh. When we originally designed the Paideia (Coached) Project in the mid-1990s, Problem-Based Learning was one of the programs that we folded into the overall design of the Project (along with Foxfire, Multiple Intelligences, "Project" Based Learning, etc.). In other words, the closest connection between PBL and Paideia is that successful Paideia Projects are often based on a clearly defined "problem" that some members of the authentic project audience have such that the audience is invested in the solution as constructed by the students working together. That said, a Paideia PBL unit would be a Paideia Project that contains relevant seminar discussion, extensive skills coaching, and a product or performance that serves as the "solution" to the problem. (Email, August 14, 2007) Part III: Teaching and Learning—Participant Expectations Collaboration and Differentiation Of primary importance to a successful PBL experience, the following student responsibilities and behaviors should be observed. Student Responsibilities and Behaviors: PBL approach requires that students work in small groups to attain their learning objectives. Teachers should be assured that learning issues are identified as they observe that, w/in groups, the learning needs tend to be somewhat diversified. In PBL students learn the skills of negotiation, mediation, and cooperation (See appendix). They learn to organize themselves and their work, to self-direct in their learning, and to determine which resources are credible and reliable. Students learn the art of contribution, they learn how to assist others in contributing, and they learn to distinguish valuable contributions and to acknowledge others for making them. Collaboration in the group is necessary to accomplish problem resolution. Life-long learning/skills make sense and are identified and practiced. Students are to be held accountable for their own learning. Next, for a successful PBL experience from an instructional standpoint, the following teacher responsibilities and behaviors should be observed: Teacher Responsibilities and Behaviors: As PBL groups become the focus of the learning situation, teachers must assume different role. Instead of sole content provider, the teacher becomes a facilitator or coach Careful formation of small groups, their dynamic and how well they function are all important considerations in the PBL process. Make learning meaningful/relevant! Problem scenarios have a real-world frame of reference; they are centered on an event that the students can imagine in their on life or in the future. By students determining what they need to know the learning that occurs is highly relevant. PBL emphasizes conceptual understanding rather than the memorization of facts. Students have to collaborate and negotiate w/in the group to accept or rule out viable solutions. PBL brings discovery, fun, and excitement to learning, something all learners love! Another outcome is the development of a process for life-long learning. Life-Long Learning: PBL is specifically designed for students to focus on reaching multiple solutions rather than one correct answer. Focusing on multiple solutions rather than on correct answer allows students to be successful in ways that have not been available during the traditional learning experiences. We define success, especially in NC, by test scores, the most right answers, etc. PBL brings a different assessment of knowledge and skills to the table. In a 21st century, global perspective, PBL explores the skills needed to survive in the global village. The value of creativity is essential in the development of life-long learning. Part IV: The PBL Process: 1. Students, either as a large group or in small groups of 4 to 6, encounter the PBL problem scenario. (Delivery comes from overhead, ppt., notes, etc.) 2. One student reads the problem aloud (thus begins the collaboration— word id, helping w/ pronunciation, etc.) Language exploration! 3. Once students have encountered the problem they begin to create a series of lists. Fact list—should itemize all the facts they have been given in the problem Need to know—lists all the information they would like to have to better understand the problem and their role in resolving the problem. Learning Issues—list comprised of things students need to look up, research, or explore in order to move forward w/ the problem resolution. Need to know or learning issue list should be followed by a plan of action that will list the next steps to be taken in order to obtain new info. Plan of Action my reflect a plan for the entire group or may be individualized by each student. 4. Teacher’s role: facilitator and guide, expert resource, for the most part though, teachers is monitoring the process and progress of the students, helping them to explore the intended learning objectives. Additional elements that contribute to the success of PBL: Group size Group work Supporting content learning Timing Pacing Teacher’s role. Micro Lesson at NE K-8 Teaching Notes: To build depth and rigor, an instructor would normally plan for 4-10 days of instruction to “solve” a PBL problem. For my demo at NE, I am doing a micro PBL Lesson. In this session you will observe the framing elements of the PBL from start to finish, with the final presentation being a “draft” that students would revisit. Normally, I think 4-5 days would be optimal for this problem. The piece missing or that you didn’t see today, would be the rigor. In a normal situation, this is how the PBL process for this problem would generally operate: I. Day 1—introduction to the problem, The Discovery Seminar, discussion and exploration of the problem organized around a selected text, and group assignments. II. Day 2—in groups, student review the problem, the mode(s) of presentation for the solution and the assessment rubric, and then begin initial work on their PBL Worksheets (Included). The PBL worksheet directs inquiry in the areas of facts, knowledge needs, learning issues, the solutions, etc. III. Day 3-Students work in groups to research the problem, generate solutions(s), and produce the “product” that presents the solution. This is the crux of the coaching piece for instructors. IV. Day 4—Same as day 3 V. Day 5—presentation of solution, assessment, next steps, inquiry projects for deeper exploration. Note: The problem never really is solved, as students are encouraged to revisit the problem and the solution to monitor results and make adjustments as necessary. In addition, students are encouraged to reflect on research, readings, discussions, etc they encountered during the specific PBL Unit, and to apply those elements to new learning. Rigor Pieces The following are pieces I use in PBL to create and encourage rigor. I. Inquiry Projects: An Inquiry Project can be used in many ways to infuse rigor and exploration into the PBL process. Below is a list of generic projects that are aligned to learning styles. These stock projects allow for student selection of inquire mode. This list is written to high school instructions, but some quick modification can make it friendly for any grade level. The list below address works over a semester; however, feel free to modify to reflect a post PBL activity for each PBL experience. Inquiry Projects Directions: From the following list, choose one project that best reflects your individual style of learning. All projects must be accompanied by a one page (typed, double spaced) Interpretative Summary that includes the following: an analysis of the overall significance of your accomplishments in completing this project a reflection on how completion of this project has impacted your learning a reflection on how completion of this project has impacted your learning 1. Consider the “works” we have explored this grading period. This would include ANY novels, plays, poems, films, etc. Compose a poem in response to a specific incident occurring in work, OR compose a poem as an overall response to that work The poem should be of significant length, reflect some type of research, and be historically accurate. Students who plan to complete this activity must participate in a 1/2 hour conference w/ instructor regarding your work. 2. Create and publish a web page that relates to a topic of study. On this web site, compile a data base of excellent Internet links that directly relate to a major topic for this grading period. The links should be student-friendly, and you should compile a short review of each link (3-5 sentences) for each link with a minimum of 25 links. 3. Design a comic strip that reflects some aspect of one of our major topics for this grading period. The strip should have 8 or more panels, should be colored, and involve some type of research. 4. Write a two act play as a response to one of our major topics from this grading period. The play should reflect some type of research, be historically accurate, and employ the conventions of a dramatic production. (Include sketches/drawings of the scenery, stage directions, lighting, etc.) 5. Write and submit an editorial essay to local paper in response to some aspect of one of our major topics for this grading period. Students completing this project should consult with instructor. 6. Create a painting as a response to one of our major works/topics. The painting should reflect some type of research. 7. Create a sculpture (choose your medium) as a response to one of our major works 8. Write an illustrated story as a response to one of our major works/topics. The story should be based upon some type of research, exhibit standard conventions, and be historically accurate. 9. Create a paper mache product that reflects some aspect of one of our major topics. The product should be based upon some type of research. 10. Compose, perform, and record a song as a response to one of our major works/topics. Thesong should be based upon some type of research, reflect historical accuracy, and you should submit a copy of the lyrics with the tape/CD. 11. Create an original model (choose your medium) that reflects some aspect of one of our major topics. The product should reflect some type of research. 12. Write and produce a TV or radio program as a response to one of our major works/topics. The program should reflect some type of research and be historically accurate. The program should be taped and/or recorded. 13. Interview someone with a connection to one of our major works/topics. Record their impressions and create a physical project. Completed project should include photos, a list of questions asked, an audio tape of the interview, and at least a partial transcription of some “moving” information noted during the interview. Also, include any research used in compiling the questions, conducting the interview, or writing the paper. 14. Create your own project that reflects some aspect of one of our major topics for the grading period. Write a proposal for your project and submit it to instructor for approval ASAP. II. Website review Web Site Review (WSR) Activity Guide Extension Activity With each problem you solve during a PBL unit, each student will be required to complete 1-3 “WEB SITE REVIEWS” (WSR). This activity is designed to help you evaluate www sources you encounter and use during the PBL process. Using the “Critical Evaluation of a Web Site: Secondary School Level” form, students will complete the following assignment: Choose a web site of particular interest to evaluate. It should be a site that has some distinguishable connection to the PBL problem. Once students locate a suitable or interesting web site, they will evaluate that site using the “Critical Evaluation of a Web Site: Secondary School Level” form. In completing a WSR, students will answer all applicable questions included in the evaluation sheet. On paper, students will a more specific evaluation of the site (paragraph form) in the “Narrative Evaluation” section of the WSR. NOTE: "Narrative Evaluation" must be typed. Students will print a copy of the FIRST PAGE ONLY from the web site under review. Students will attach the above copy as a cover page for the WSR turned in for evaluation. III. Student Responsibilities: Students will be held accountable for the following: Following directions for selecting a WSR Following directions for formatting the WSR Completing all requested and applicable information in the WSR form. Typing the "Narrative Evaluation" section (1 page minimum, DS). Working individually (This is NOT a group effort). Turning in all 3 components of the assignment (Cover page, evaluation questions, and the Narrative Evaluation). Turning all WSR’s in on time Website Review Next Page CRITICAL EVALUATION OF A WEB SITE: SECONDARY SCHOOL LEVEL WEB SITE REVIW FORM (WSR) URL of Web page you are evaluating: http://______________________________________________ Name of the Web Page: ____________________________________________ I. Technical and Visual Aspects of the Web Page Does the page take a long time to load? YES / NO Do the pictures add to the page? YES/ NO / NOT APPLICABLE Is the spelling correct on the page? YES / NO Are there headings and subheadings on the page? YES / NO ·If so, are they helpful? YES / NO Does the author sign the page? YES /NO Is the author's e-mail address included? YES / NO Is there a date of last update? YES / NO •If so, is the date current? YES / NO Is there an image map (large clickable graphic w/ hyperlinks) on the page? YES / NO On supporting pages, is there a link back to the home page? YES / NO Are the links clearly visible and explanatory? YES /NO Is there a picture or sounds included? •If so, can you be sure that a picture or sounds has not been edited? YES / NO •If you are not sure, should you accept the information as valid for your purpose? YES/NO II.Content Is the title of the page indicative of the content? YES / NO Is the purpose of the page indicated on the home page? YES / NO When was the document created? __________________________ Is the information useful for your purpose? YES / NO Would it have been easier to get the information somewhere else? YES / NO Did the information lead you to other sources that were useful? YES / NO Is a bibliography of print sources included? YES / NO Is the information current? YES /NO Does up-to-date information matter for your purpose? YES / NO Does the information appear biased? YES / NO Does the information contradict something you found somewhere else? YES / NO III. Authority Who created the page? ____________________________________________ What organization is the person affiliated with?__________________________ Has the site been reviewed by an online reviewing agency? YES / NO Does the domain (i.e. edu, com, gov) of the page influence your evaluation of the site? YES/NO Are you positive that the information is true? YES / NO What can you do to prove that it is true? _________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ Are you satisfied that the information is useful for your purpose? YES / NO ·If not, what can you do next? _____________________________________ IV. Narrative Evaluation Looking at all of the data you have collected above while evaluating the site, explain why this site is valid for your purpose. Address the aspects of authenticity, authority, bias, and subject content on the site. In addition, please note the most interesting piece of information you discover and explain why you find it interesting. Finally, rank the site on a scale of 1-5 (5 being the highest) and explain why you feel your ranking is justified. NOTE: The Narrative Evaluation should be typed (double spaced, 12 inch font, one page in length) and either attached or cut and pasted into this WSR form. ©1996 Kathleen Schroek (kschrock@capecod.net) and revised for J. H. Rose High School Paideia II and III: Alexander/Jester 2002-2003. III. Discovery Seminar What is the “Discovery” Seminar? The Discovery Seminar is designed to begin the information flow that students will need to solve the problem. After students are introduced to the problem, the DS becomes the jumping off point for entrance into the problem. Like the traditional Socratic Seminar, the Discovery Seminar will start with a thought-provoking text chosen to stimulate entry level discussion on subject associated with the problem to be solved. From this point on, the DS takes on a seminar definition of its own. The Discovery Seminar differs from the pure Socratic Seminar in that the teacher has a dualistic role. In a pure Socratic Seminar, the instructor directs and moderates discussion, never having an actual participatory role in that discussion. The instructor, with a Discovery Seminar plan in hand, may choose to wear any number of different hats, including that of participant. The instructor may sway between participant and moderator, at times probing the students with questions, at other times interjecting short bursts of didactic instruction. (Note: Instructors must be cautious not to interject personal bias on the topic during discovery so that students’ thinking remains uninfluenced—this is sometimes a difficult challenge for teachers. Stay on guard!} The instructor may act as a coach during the Discovery Seminar, answering questions, or NOT answering questions that arise as students’ thinking begins to gain focus. As to the issue of grouping students for the problem, the instructor should note patterns in student thinking during the DS. These observations should or can be utilized to group the students after the DS is completed. The instructor may play devil’s advocate during the discussion to challenge students’ thinking. The point is that, with a problem-related text in hand, the instructor may choose to make the DS whatever works best for learning situation at hand. The DS is an instructional strategy, not an instructional activity. See Attached Discovery Seminar Plan Template from a PBL Unit on Gangs