PT CASE: COPD EXACERBATION

advertisement

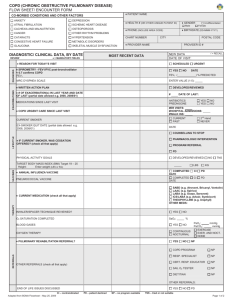

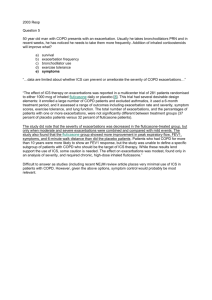

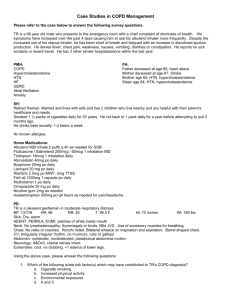

PT CASE: COPD EXACERBATION (INSTRUCTOR VERSION) By Dan Waldman, MD Department of Family and Community Medicine GOALS FOR SESSION At the end of the session, the residents should: 1. Understand the initial approach to the urgent treatment of a patient with a COPD Exacerbation. 2. Understand the different modalities typically utilized in the treatment of COPD Exacerbations. 3. Recognize patients who may need more aggressive intervention, such as Positive Pressure Ventilation, or Mechanical Intubation 4. Understand some basics of the magnitude of the societal burden of chronic COPD and COPD exacerbations. CASE PRESENTATION WITH QUESTIONS A 65 year old Cuban male comes to the ED because of shortness of breath. He notes that over the last 2-3 years he has had gradual worsening of his ability to exert himself without feeling out of breath, and it has been acutely worse for the past week, including a worsening productive cough. On questioning, he reveals that he coughs almost every morning as well, and this has been going on for even longer, perhaps 4-5 years. The cough is now productive of yellowish-brownish sputum. He denies chest pain, fevers, chills or night sweats. He has no history of lower extremity edema. The rest of his review of systems is negative. Other than an appendectomy when he was in his 20’s, the patient denies any significant past medical history. He denies taking any medications, but does state that a year ago he went to a walk-in clinic for cough and got some kind of inhaler, which he used over the course of a month or two until it was gone. He lives in an apartment with his wife, and has smoked a pack of cigarettes a day for 40 years. On exam, his BP is 144/88 mmHg, HR is 98, respiratory rate is 28 breaths per minute. His temp is 97.6. Oxygen saturation is documented as 93% on 4 L. You find him sitting up in the ED bed, leaning forward. He appears uncomfortable with labored 1 breathing and his lips are bluish. There is no cervical lymphadenopathy, JVD or carotid bruits. Chest exam shows mild intercostal retractions seen around the anterolateral costal margins. Wheezes and rhonchi are present bilaterally, without crackles. Heart exam is unremarkable, though the heart sounds are distant. Lower extremities show no cyanosis, clubbing or edema. Q. What is the most likely diagnosis? A. COPD with acute exacerbation. Q. What is the most appropriate next diagnostic step? A. Given the patient’s respiratory difficulty seen on exam and possible hypoxia, an ABG would be helpful to measure adequacy of oxygenation (PaO2) and ventilation (PCO2). In this case, the ABG was taken and found to be 7.32/58/86/30. It was done while the patient was on room air. Q. What is the interpretation of this ABG? (ABG values not given on student version) A. This ABG shows marked respiratory acidosis with a partial compensatory metabolic alkalosis. The patient’s room air saturation is subsequently found to be 84-86%. You vaguely remember something about some kind of respiratory drive and suppressing it with too much oxygen. You also remember that some people disputed this. Q. What should your target O2 saturation be for this patient? A. Target oxygen saturation should be 90-92%. Hypercapnia can accompany the aggressive use of supplemental oxygen. While decreased alveolar ventilation caused by suppression of the hypoxic drive does not appear to play a major role by itself, this O2 target can help maximize hemoglobin saturation, and lessen the likelihood of hypercapnia from ventilation/perfusion mismatches. Placing patients with chronic COPD and acute respiratory failure on 100% O2 has been shown to increase CO2 levels, by 23 +/- 5 mmHg in one study. (Ambier M, 1980) Q. If this patient also had a history of heart failure, what test might be helpful to exclude CHF as playing a role in the patients dyspnea? A. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) can be used to help distinguish heart failure from other causes of dyspnea. Use of BNP in the ED for patients with dyspnea and a history of pulmonary disease can decrease the likehood of admission (81% vs 91%; P = .034) and decrease time spent in 2 the hospital (9 days vs 12 days; P = .001), as well as overall decreased cost of care ($4841 US vs $5671 US; P = .008) (Mueller C, 2006). In March of 2007, UNM adopted a new BNP test. This propeptide test is listed as having a cutoff for a negative test as ≤125pg/mL for patients less than 75, and ≤450 pg/mL for patients more than 75 years old. The “ProBNP Investigation of Dyspnea in the Emergency Department (PRIDE)” study evaluated this methodology and found the following results ( Januzzi JL Jr, Apr 2005) (note: this table appears at the end of the student version as well): Optimal Cut Point (pg/mL) 900 Sensitivity (%) 90 Specificity (%) 85 PPV (%) 76 NPV (%) 94 <50 years old 450 93 95 67 99 ≥ 50 years olf 900 91 80 77 92 300 99 68 62 99 RULE-IN Cut Points All Patients RULE-OUT Cut Point All Patients You obtain a BNP, and it’s 185. Additionally, a chest XRay shows only hyperinflation, without acute infiltrates. Q. What are the mainstays of treatment of acute COPD Exacerbations? (answers to this question are also on the student version) A. Routine treatment includes use of bronchodilators, systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics. For patients sick enough to be hospitalized, oxygen and possibly mechanical ventilation are often used. 1. Bronchodilators a. Inhaled Beta Adrenergic Agonists 3 Bronchodilators: the mainstay of therapy for acute exacerbations. Rapid onset of action and efficacy in producing bronchodilation. Data indicate similar efficacy with nebulizer or MDI, but MDI requires patients to be more alert, and nebs still recommended by many experts. 2.5 mg of albuterol is as efficacious in improvement of spirometry and clinical outcomes, but 5mg still used often.(Nair, 2005). b. Anticholinergic Bronchodilators May be used in combination with beta adrenergic agonists to produce bronchodilation in excess of that achieved with either agent alone. 2. Systemic Corticosteroids Reduce 30 day treatment failure rate (23% vs 33%), 90 day treatment failure rate (37-48%) and length of hospital stay (8 vs 10 days), while improving lung function (Niewoehner, 1999). Oral steroids have been shown to be effective for outpatient therapy, while serious COPD exacerbations requiring hospitalization usually call for starting with intravenous steroids, though data is limited. Q. What about using steroids when the patient also has an underlying infection, such as community acquired pneumonia? A. This is an interesting question that often comes up and is difficult to answer. We do know that COPD is a common co-morbidity in hospitalized patients with CAP, and many of these patients receive steroids. It seems that being on chronic steroids and subsequently developing pneumonia increases mortality, as does just having the diagnosis of COPD (Restrepo., 2006), but it is unclear what affect acute administration of systemic steroids has on otherwise nonimmunosuppressed patients with CAP. Some preliminary studies have actually shown improved outcomes with the administration of systemic steroids in CAP, in patients without COPD (Confalonieri M, 2005). For now we can only say that patients with the dual diagnosis of COPD and CAP often receive system steroids, and the implications are not entirely clear. Q. What is the usual dose and time course of systemic corticosteroids in this condition? A. While there is no “correct” dose and taper, the usual starting dose for admitted patients with COPD exacerbations is 1-2mg per kg of methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol) given every 6 to 12 hours. After 2-3 days of IV therapy, the patient can be switched to oral administration, usually starting at 60mg prednisone daily, and tapered down for a total course of 2 weeks of treatment. 8 weeks of steroids seems to offer no benefit over 2 weeks (Niewoehner, 1999). Future directions may include 4 studying which specific patient populations need to be tapered more slowly, particularly older men with severe irreversible airway obstruction (O'Brien A, 2001) . 3. Antibiotics Antibiotics are recommended for acute exacerbations of COPD that are characterized by “increased volume and purulence of secretions.” They decrease mortality and treatment failure rates, while accelerating improvement of peak expiratory flow rates (Ram, 2006). Some advocate for the use of broad spectrum antibiotics in older patients (over 65), patients with more frequent exacerbations or patients with more severe exacerbations. There is no clear data to support this position at present. Data on improvement with antibiotics has been largely studied with doxycycline, trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole and amoxicillin (Anthonisen NR, 1987), usually with a 10 day course. Some experts believe sicker hospitalized patients should receive antipsuedomonal coverage, and recommend treatment of the most serious exacerbations with a 3rd generation cephalosporin or an augmented penicillin plus a fluorquinolone or aminoglycoside for synergy. Examples of this coverage would be ceftriaxone or unasyn plus levaquin or tobramycin (Hunter M, 2001). 4. Mucokinetic regimens The use of mucolytic agents, chest physiotherapy, intermittent positive pressure breathing and directed coughing have not been shown to be effective. 5. Methylxanthines Methylxanthines do not appear to significantly help in patients with mild to moderate exacerbations of COPD. They may be of limited use in patients with severe exacerbations, but they have a narrow therapeutic index and high risk of toxicity. 6. Oxygen therapy Venturi masks can provide precise FiO2 values, which can help monitor oxygen status over time in patients where nasal cannula is insufficient. You admit the patient, write orders and then start seeing another admission. You are called by the ED nurse who wants to let you know that your admitted patient with 5 COPD looks worse, and is now somnolent and confused. You ask the nurse to draw another ABG and go assess the patient. Q. When should non-invasive positive pressure ventilation be considered? A. In situations where there is a need for ventilator assistance, as indicated by hypercapnia associated with depressed mental status, profound acidemia, worsening dyspnea and/or worsened oxygenation (e.g. ratio of PaO2 to FiO2 less than 200). It is possible that our patient’s hypercapnia is worsening and causing somnolence and confusion. Benefits of positive pressure-ventilation are lower rates of intubation, lower in-hospital mortality rates and shorter hospital stays (Stoller, Mar 2002). Q. Which patients are likely to need intubation? A. Patients with respiratory arrest, medical instability (hypotensive shock, cardiac ischemia), an inability to protect their airway, excessive secretions, agitation or uncooperativeness (or those with a facial structure that precludes proper mask fitting) are likely to need intubation. ADDITIONAL BACKGROUND INFORMATION (ALSO IN STUDENT VERSION) 6 The American Thoracic Society defines COPD as a disease process involving progressive chronic airflow obstruction because of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or both. Chronic Bronchitis is defined clinically as excessive cough and sputum production on most days for at least 3 months during at least two consecutive years. Emphysema is characterized by chronic dyspnea resulting from destruction of interalveolar septa. Emphysema occurs in the distal or terminal airways and involves both airways and lung parenchyma. In the United States, age-standardized death rate amongst persons with COPD doubled from 1970 to 2000 (Jemal A, 2005). COPD is now the 4th leading cause of death in the U.S., and the only leading cause of death for which the mortality rate is increasing. Cigarette smoking is implicated in 90% of COPD cases. The strongest predictors of mortality are older age and a decreased forced expiratory volume per second (FEV1). 60 year old smokers with chronic bronchitis have a 10 year mortality rate of 60 percent, which is four times higher than the mortality rate for age-matched asthmatics (Hunter M, 2001). Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency should be suspected when COPD develops in a patient younger than 45 years who does not have a history of chronic bronchitis or tobacco use, or when multiple family members develop lung disease at an early age. Don’t forget to immunize patients with COPD (pneumococcal and influenza vaccines) BIBL I OGR AP H Y Ambier M, M. D.-E. (1980). Effects of the administration of O2 on ventilation and blood gases in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during acute respiratory failure. Am Rev Respir Dis , 122:747-54. Anthonisen NR, M. J. (1987). Antibiotic Therapy in Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Ann Intern Med , 106:196-204. Confalonieri M, U. R. (2005). Hydrocortisone infusion for severe community-acquired pneumonia: a preliminary randomized study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med , 171:242–248. Hunter M, K. D. (2001). COPD: Management of Acute Exacerbations and Chronic Stable Disease. Am Fam Physician , 64:603-612. Januzzi JL Jr, e. a. (Apr 2005). The N-terminal Pro-BNP investigation of dyspnea in the emergency department (PRIDE) study. Am J Cardiol , 95(8): 948-54. Jemal A, W. E. (2005). Trends in the leading causes of death in the United States, 1970-2002. JAMA , 264:1255-9. Mueller C, L.-K. K. (2006). Use of B-type natriuretic peptide in the management of acute dyspnea in patients with pulmonary disease. Am Heart J , 151:471-77. Nair, S. T. (2005). A randomized controlled trial to assess the optimal dose and effect of nebulized albuterol in acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest , 128:48. Niewoehner, D. E. (1999). Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med , 340:1941. O'Brien A, R.-M. P. (2001). Effects of withdrawal of inhaled steroids in men with severe irreversible airflow obstruction. Am J Resp Crit Care Med , 164:365-371. Ram, F. R.-R.-N. (2006). Antibiotics for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev , CD004403. Restrepo MI, M. E. (2006). COPD is associated with increased mortality in patients with communityacquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J , 28:346-35. 7 Stoller, J. (Mar 2002). Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. NEJM , 988994. Post Module Evaluation Please place completed evaluation in an interdepartmental mail envelope and address to Dr. Wendy Gerstein, Department of Medicine, VAMC (111). 1) Topic of module:__________________________ 8 2) On a scale of 1-5, how effective was this module for learning this topic? _________ (1= not effective at all, 5 = extremely effective) 3) Were there any obvious errors, confusing data, or omissions? Please list/comment below: 4) Was the attending involved in the teaching of this module? Yes/no (please circle). 5) Please provide any further comments/feedback about this module, or the inpatient curriculum in general: 6) Please circle one: Attending 9 Resident (R2/R3) Intern Medical student