Report on University of Maryland University College

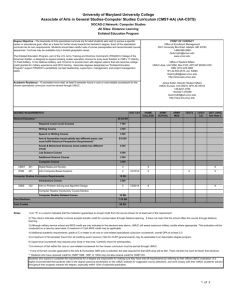

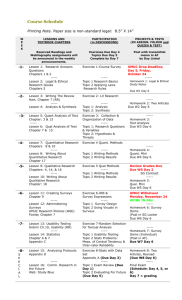

advertisement