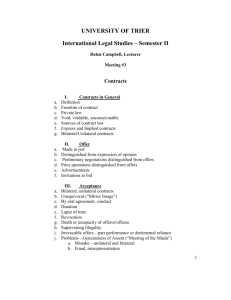

110-Audrey-Contracts-Final-Case

advertisement