Bushy-Run-Staff-Ride-Participant-Battle-Book

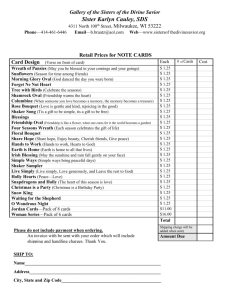

advertisement

FORT PITT CHAPTER OF THE ASSOCIATION OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY ~ PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM ~ The Battle of Bushy Run ~ 5-6 August 1763 PAGE 1 of 13 PURPOSE The purpose of this Professional Development session is to further the professional development of current and former U.S. Army leaders or associates of the U.S. Army who are members of, guests of, or associated with the Fort Pitt Chapter of the Association of the United States Army. OBJECTIVES The objectives of this staff ride are: A. To expose attendees to the dynamics of battle, especially those factors which interact to produce victory and defeat. B. To expose attendees to the "face of battle," and the timeless human dimensions of warfare. C. To provide a case study in the application of the principles of war. D. To provide a case study in the operational art. E. To provide a case study in leadership and unit cohesion. F. To provide an analytical framework for the AUSA future systematic study of campaigns and battles for Leader Development. G. To encourage leaders and members to study the profession of arms through the use of military history. PAGE 2 of 13 BASIC INFORMATION The Battle of Bushy Run The “Swing Action” on the Second Day of Battle at Bushy Run (Painting by Don Troiani). Commanders BRITISH / COLONIAL Henry Bouquet 450-500 ~60 killed NATIVE Guyasuta Keekyuscung (KIA) Strength 110-500 Casualties and Losses 50 killed 60 wounded 15 missing The Battle of Bushy Run was fought from August 5th to August 6th, 1763 in Western Pennsylvania near the current town of Jeannette, PA. The battle was a pivotal, although small, engagement of Pontiac’s War – an inevitable conflict after the close of the French and Indian War (or Seven Year’s War) after the defeat of the French led to a power vacuum in America. Colonel Henry Bouquet, a Swiss mercenary in the service of Great Britain, led a mixed force of 400 British soldiers and rangers from Carlisle, PA in July to relieve the besieged PAGE 3 of 13 Fort Pitt and end a series of unchecked attacks against frontier outposts. The British column under the command of Colonel Bouquet fought against a combined force of Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, Wyandot and Huron warriors. Though the British suffered serious losses, they routed the tribesmen and successfully relieved the garrison of Fort Pitt. The British victory at Bushy Run was the critical turning point in Pontiac's War. It also prevented the capture of Fort Pitt (now Pittsburgh) and restored lines of communication between the frontier and eastern settlements. The British victory helped to keep the "gateway to western expansion" open. The 213 acres that comprise Bushy Run Battlefield, in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, can be viewed as one large historical entity. The events that transpired here in August 1763 set Bushy Run apart as a place of historical significance. The battle near Bushy Run and the events of Pontiac's War leading to the battle add to the understanding of the Indian-European culture clash, which is an important theme in American history. The battle also has a place in the broader study of American settlement and expansion, and possesses great significance in the realm of British, American and Indian military history and is an excellent study of what leadership – properly schooled and trained – can do under fire. PRELUDE During the French and Indian War, a nine year period spanning from 1754 to 1763, the British sought to win the loyalty of the Delaware, Shawnees, and Western Senecas away from France. Through peace talks and proclamations, leaders of these tribes believed that in exchange for their neutrality in the war, colonial encroachment of land west of the Allegheny Mountains would cease after the fighting ended. Within three months of the official conclusion of the French and Indian War, England’s promises were broken. Once the struggle with France ended, settlers moved in ever-increasing numbers to the frontier lands. Furthermore, the British continued construction of Fort Pitt, a brick and stone fortification larger than any they had built in North America. General Jeffery Amherst, who in late November 1758 was appointed commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America, told the Native Americans that Fort Pitt was to protect them, but had no answer when they asked from whom. One of the fort's primary functions was to protect and control trade with the Native Americans. In General Amherst's view, the Indians were subjects of the British crown, and it was, therefore, not necessary for the government to make special treaties with them or to continue the practice of making gifts to the various tribes. The British also limited the amount of guns, gunpowder, and shot that could be sold to Native Americans. With the French no longer prominent contenders, British appeasement of the Indians ceased to be vital. For many, these former allies were now an PAGE 4 of 13 impediment to progress, although the British remained eager to capitalize on the lucrative fur trade. When Native Americans realized the balance of power had shifted, voices were raised offering suggestions on how they should respond to the British. A Delaware prophet, Neoliane, preached a return to natural values and the lifestyle of their ancestors. He entreated his people to throw off the influences of European traders, to abandon their cooking kettles and their clothing, and return to the time-honored Native American ways. Neoliane proclaimed that if the Native Americans gave up European ways, the Great Spirit would return to their land. Meanwhile, in 1761, in the western and central Great Lakes regions, Pontiac, the Ottawa war chief, was gaining power. Pontiac wanted the French to return to the western frontier, and the diverse tribes to band together to fight the British. He succeeded in enlisting the support of several tribes in his region, but not eastern tribes, including the Delaware, Shawnee, and Iroquois Six Nations. Although the eastern tribes regarded the British as troublesome, they were not yet ready to launch a major military offensive. Pontiac decided to attack, and with allied Great Lakes tribes he besieged Fort Detroit on May 8, 1763. While surrounding Fort Detroit and holding it under siege, Pontiac's Rebellion spread into Pennsylvania, although the Ottawa chief never left the Great Lakes region. By the end of July of that year, nine British forts were captured, a tenth fort abandoned, and Forts Pitt and Detroit were under siege. It was the success of his efforts that prompted the Delaware, Shawnee, and Western Seneca to attack and destroy Pennsylvania's Fort LeBoeuf, Fort Venango, and Fort Presque Isle (all former French forts in Western PA) and to begin a siege at Fort Pitt in June 1763. The geographic area of the rebellion affected included the present states of Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin and parts of Maryland and West Virginia. As the Indians thoroughly controlled the frontier and speed of communication was limited to what a horse could travel in a day (20-30 miles), information about the war filtered slowly east to the British high command in the east. Once the scope of the situation was realized in late June, an expedition was ordered by Lord Amherst to march west to lift the siege of Fort Pitt and then to proceed north and west to reestablish fallen forts. MOVEMENT TO CONTACT Colonel Henry Bouquet, a Swiss born professional soldier, commanded the expedition as it left Carlisle, PA on July 18th. Departing Carlisle on that day was a force of about 500 British soldiers, including the 42nd Royal Highland Regiment, the 60th Royal American Regiment, the 77th Royal Highland Regiment and colonial militia and rangers, along with wagons loaded with flour for the besieged troops at Fort Pitt. British soldiers who fought at Bushy Run were primarily from regular British regiments. Those in the 60th were raised in the colonies of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, and Delaware. The other two regiments came from the Highlands of Scotland. PAGE 5 of 13 As these troops marched, Fort Pitt, already being heavily harassed, came under full siege. Entrapped within were nearly 1400 souls, mostly panic-stricken frontier families who had fled there seeking safe haven from marauding war parties. Large contingents of Native forces made communication - into or out of the fort - impossible. As the Bouquet column pushed westward, it had no idea what lay ahead. Earlier, in 1755, it had been General Braddock plodding along in the forest, expecting ambush. It came, all too soon, and resulted in the Braddock's Defeat debacle. Now, it seemed it was Bouquet's turn. Though his force was comprised of grizzled veterans, many were wounded or sick. At Fort Bedford (now Bedford, PA), Bouquet left his sick and invalids for about 30 frontiersmen to act as scouts. Upon reaching Ligonier, on August 2, Bouquet further lightened his load by leaving behind his oxen, artillery, and supply wagons, transferring the flour supply to packhorses. With no word from Pitt, and the Indians certainly aware of his presence, the next 40 miles must be covered as quickly as possible. Early warning, courtesy of the newly obtained frontier scouts, might be just the tonic to avert disaster. On August 4, 1763, Bouquet left Fort Ligonier anticipating an attack from Indian forces. Anticipating an assault by the natives somewhere along the route, Bouquet’s best guess was that the attack would occur at the Turtle Creek defiles (near Pitcairn) and he wanted to pass through this narrow pass at night to try to avoid the enemy who had already been watching his movements. He never made it Indian scouts observed Bouquet's army marching west along the Forbes Road and reported this to the large force of Indians surrounding Fort Pitt. The Indians decided to temporarily end their siege and attack the British expedition in the open. As he continued his march and in order to avoid the deteriorated Forbes Road leading to Pittsburgh, Colonel Bouquet decided to turn off onto the newer South Fork heading towards the Bushy Run Post. This outpost, under the supervision of Andrew Byerly, was used by British troops traveling to and from Fort Pitt and Fort Ligonier to feed and water horses, store supplies, and as a stopover for couriers traveling between the forts. Four days before the Battle at Bushy Run, a party of Mingoes stopped at the supply post and warned everyone to "quit the place or they would all be killed in four days!" British families in the area had been burned out without any warning. On the day before the Battle of Bushy Run, the siege at Fort Pitt ended abruptly and the Indians withdrew. It's believed that all or most of those taking part in the siege covered the twenty-five-mile distance to Bushy Run and were on hand for the battle that began about one o'clock in the afternoon on August 5, 1763. Colonel Bouquet was just making the turn on the South Fork when the Native Americans attacked from the brow of the wooded hill directly in front of them. PAGE 6 of 13 THE BATTLE – FIRST DAY On August 4 at 1300 hours, after the British troops had marched about 17 miles, the mixed army of Highland and Royal American troops, Virginia militia and rangers and pack horse drivers crested Edge Hill on their way to what was left of Bushy Run station and were attacked by the natives. Bouquet sent the 42nd forward to repulse the enemy until the troops and strategy were set. The troops moved forward, but being attacked on all flanks, fell back to protect the convoy, part of that convoy being the famous "flour bags" which were soon to be a lifesaver for His Majesty's troops. Bouquet ordered two companies of the 77th Regiment’s light infantry (a relatively new concept of highly mobile troops) to push the Indians from their superior position. The Highlanders took heavy casualties. It was to become a situation that closely resembled the predicament of Braddock years earlier ... an advance guard ran into hostiles, support was sent forward, and after some stiff firing, a bayonet charge sent the Indians from whence they had come. The apparent successful repulses by the bayonet were a ruse, for almost immediately renewed fire broke out every time, from the woods on both flanks and the rear of the main British force. It was Braddock's Defeat all over again ... or was it? It certainly could have been, but the difference here was the maintenance of order. And that occurrence rests squarely on the shoulders of the troops' confidence in their commander. A pitched battle ensued with neither side achieving a decisive victory. Bouquet formed up in a near-hollow square on Edge Hill. The Indians continually dashed forward and fire was exchanged numerous times. Often a bayonet charge put an end to things for a time. The scenario repeated ... all day. The Grenadiers had formed an extended line, keeping up a heavy fire as troops from the 42nd and 60th took up flanking positions. The 77th volley fired, making huge swaths through the brush to dispense of the attackers. The battle raged on for the next 7 hours. Musketry, screams, savage yelps, guttural commands, the crack of rifles, continued to near dark. As the day turned towards night, the British had more than 50 casualties, and they were without water for horses or men. That evening, by the light of the stars and moon at the top of the ridge where the battle had raged during the day of the 4th, a "flour bag" redoubt was constructed on Edge Hill so that, as the dawning of the 5th of August came forth, the camp was protected by an angled wall built of large sacks filled with flour and laid on their sides like brick. Packhorses, supplies and wounded men were moved into the redoubt, supplies to the left flank and the hilltop surrounded with British soldiers. As night fell, British forces geared themselves for the coming morning battle. THE BATTLE – SECOND DAY At sunrise as the sun began to climb, amid the groans of the wounded British troops, the native forces renewed their persistent fire and probing forays around PAGE 7 of 13 the small British circular defenses the following morning. By mid-afternoon of August 6, Bouquet’s position was becoming increasingly precarious. Without water, running low on ammunition and with an increasing casualty list, defeat and slaughter of the small force was imminent. However, Bouquet had tailored his actions to that of the attacking Indians, essentially using their own strategy against them. The natives followed their customary practice of forming a loose horseshoe around the enemy, leaving the back open in order to force a retreat, which would make it easier to kill the fleeing soldiers. The natives looked for a weakness in the British line, and then attacked that section. Whenever the soldiers moved to strengthen a weak spot, the warriors would withdraw and attack in a different area. This continual shifting left the British confused and uncertain of their enemy's position and numbers. When the British attempted to retreat, the Native Americans folded in their horseshoe and attacked in mass. Bouquet now ordered two companies of light infantry at the front of his defenses to withdraw, feigning a retreat to the southeast. The withdrawal created the illusion of a retreat and opened a controlled area of Bouquet’s line. The Indian forces fell for the perceived weakness and moved into the void with a heavy fire, attacking the thinned line of troops to the front. Bouquet had ordered his grenadiers and the company of American rangers to his left flank to protect his supply train. Just as the Indians “…thought themselves masters of the camp…”, Bouquet moved up two companies in support, closing the gap, while the grenadiers and rangers moved out from cover in the south on the leeward side of Edge Hill and laid down a devastating supporting fire on the native flank, laying down volley after volley and then “made terrible havock” with the bayonet. In this action, the natives probably lost thirty to fifty warriors, including some of the most prominent. When the Indians retreated, Bouquet ordered his light infantry to pursue them. The battle ended as a British victory. THE AFTERMATH The battle cost the lives of 50 British soldiers, including 29 of the 42nd Highlanders, seven of the 60th Royal Americans dead, six of the 77th Highlanders, and eight civilians and volunteers dead. The confederacy of the Delaware, Shawnee, Mingo, Wyandot and Huron also suffered an unknown number of casualties, including two prominent Delaware chiefs; estimates from contemporaries place the total of Indian losses at about 60.. The native warrior Killbuck later told Sir William Johnson (the British Indian Agent in New York) that only 110 warriors were engaged. Bouquet estimated the natives brought an equal number to the action as his own force. One contemporary report claimed that 20 Indians were killed and many more wounded. The result of the battle invoked "widespread relief on the frontier", since the native warriors had been defeated on their own ground. For Native Americans, Pontiac's Rebellion represented a turning point. It was one of the most important conflicts in their history since it determined whether British PAGE 8 of 13 colonization could be limited. This was also a war to see how far the Native Americans could be pushed west. Indian leaders, realizing they must deal with the Europeans, who were predominant, had tried their best to negotiate settlements. But their hopes were disappointed and betrayed. Pontiac's Rebellion reflected that native leader’s own understanding that treaties were not going to be honored. The concept of Native American hunting grounds west of the Alleghenies was now abandoned, and the door open for the expansion of the frontier. Even more significant for Native Americans was the introduction of the containment concept, with decrees stipulating that Indian populations be kept west of the Alleghenies. INTERESTING FACTS Guyasuta is buried at the Custaloga Town Scout Reservation, a camp belonging to the Boy Scouts of America located along French Creek at the former site of his village in French Creek Township, PA. In Pittsburgh, Guyasuta is honored (along with George Washington), with a large public sculpture called “Point of View”, which overlooks Point State Park. The Guyasuta Volunteer Fire Department in O’Hara Township, PA is named after him and a life-sized statue stands at the intersection of Main and North Canal Streets in Sharpsburg, PA. The Bushy Run Battlefield Site and Museum has an interesting history. Just months after the battle, the site of the conflict was of interest to those in the region. By 1837, most of the battlefield was sold to a Mr. Lewis W. Gongaware, one of the largest farm owners in the county, who worked the land until about 1880. The farm was then sold to a Mr. John Wanamaker, and his descendants owned the land until the 1920s when it was purchased by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Bushy Run Battlefield is the only historic site or museum that deals exclusively with Pontiac's War. The battlefield today is topographically intact. Combatants' positions and maneuvers can be "seen" and understood and the wooded acres (90 acres) give a sense of the original environment at the time of the battle. There is some evidence that Colonel Bouquet considered probably one of the first recorded uses of germ warfare, where he and General Jeffrey Amherst discussed distributing blankets infected with the small pox virus among the Indians in order to cause an epidemic. Colonel Henry Bouquet did more than adapt his military tactics to the fighting style of the Native Americans. He and fellow British commanders also adopted some of their equipment. The tomahawk, for example, was added to the soldier's accoutrements because it was far more utilitarian than the sword. Also borrowed from the Indians was the tumpline, a strap used to carry heavy loads. Enlisted men found it helped them carry their blankets and spare clothing. Shot pouches, powder horns, and leggings were also taken up by the British. PAGE 9 of 13 The following year, Colonel Bouquet wrote a paper called “Reflections on War with the Savages in North America”. In it, he acknowledged that American provincials and woodsmen were best suited for woods warfare. . The strategy Bouquet employed to contend with what he called the Native Americans' "running fight" is still being studied by historians because it marks one of the first instances that light infantry was used for the purpose it was intended. NATIVE COMMANDER Guyasuta (1725 (?) – c.1794) was an important leader of the Seneca nation of the Iroquois Confederation in the second half of the eighteenth century, playing a central role in the diplomacy and warfare of that era. His name is phonetically rendered as “KayahsotaÔ, and the many spelling variations included Kiasutha, Kiasola, and Kiashuta. There are some records that Guyasuta probably served as a scout for George Washington in 1753, although he sided with the French in the French and Indian War and played a role in the defeat of the Braddock Expedition against Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh) in 1755. He played a major role in Pontiac’s War – with a significant enough contribution that some historians referring to that conflict as the Pontiac-Guyasuta War. At the beginning of the American War of Independence, the revolutionaries attempted to win Guyasuta to their cause, however like most Iroquois, he choose to side with the Crown. He fought throughout the conflict with the British and PAGE 10 of 13 played a significant role at the Battle of Oriskany in New York. After the war and in his later years, Guyasuta worked to establish peaceful relations with the new United States. BRITISH COMMANDER – COL HENRY BOUQUET Henry Bouquet (1719 – September 2, 1765) was a prominent British Army officer in the French and Indian War and Pontiac's War. Bouquet is best known for his victory over Native Americans (American Indians) at the Battle of Bushy Run, lifting the siege of Fort Pitt during Pontiac's War. Bouquet was born into a moderately wealthy family in Rolle, Switzerland. The son of a Swiss roadhouse owner and his well-to-do wife, he entered military service at the age of 17. Like many military officers of his day, Bouquet traveled between countries serving as a professional soldier. He began his military career in the army of the Dutch Republic and later was in the service of the Kingdom of Sardinia. In 1748, he was again in Dutch service as lieutenant colonel of the Swiss guards. He entered the British Army in 1756 as a lieutenant colonel in the 60th Regiment of Foot (The Royal American Regiment), a unit made up largely of members of Pennsylvania's German immigrant community. After leading the Royal Americans to Charleston, South Carolina to bolster that city's defenses, the regiment was recalled to Philadelphia to take part in General John Forbes' expedition against Fort Duquesne in 1758. PAGE 11 of 13 While Bouquet traveled down the road from Fort Bedford, his troops were attacked by French and Indians at Loyalhanna, near present Ligonier, Pennsylvania, but the attack was repulsed and they continued on to Fort Duquesne, only to find it razed by the fleeing French. Bouquet ordered the construction of a new British garrison on the site of Fort Duquesne. Bouquet is given credit for naming the new garrison Fort Pitt and the village that quickly grew up around it Pittsburgh. On August 5, 1763, Bouquet and a relief column organized to lift the siege of Fort Pitt were attacked by warriors from the Delaware, Mingo, Shawnee, and Wyandot tribes near a small outpost called Bushy Run, in what is now Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. In a two day battle, the tribes were defeated by Bouquet's force and Fort Pitt was relieved. The battle marked a turning point in the war. It was during Pontiac's War that Bouquet gained a certain lasting infamy. In a series of letters during the summer of 1763 between Bouquet and his commander, General Jeffery Amherst, the idea was raised of infecting the Indians who had besieged Fort Pitt with smallpox by giving them infected blankets from the fort's smallpox hospital. Amherst wrote to Bouquet, then in Lancaster, on about June 29, 1763: "Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among those disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them." Bouquet agreed, replying to Amherst on July 13: "I will try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets that may fall in their hands, taking care however not to get the disease myself." Amherst responded on July 16: "You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method that can serve to extirpate this execrable race." Evidence that at least some measure of this plan was carried out is provided by the journal of William Trent, the commander of the militia at the fort, although it appears that Trent had already carried out the plan before Amherst had proposed it to Bouquet: By the autumn of 1764, Bouquet had become the commander of Fort Pitt. To subdue the ongoing Indian uprising, he led a force of nearly 1,500 militiamen and regular British soldiers from the fort into the Ohio Country. On October 13, 1764, Bouquet's army reached the Tuscarawas River. Shortly thereafter, representatives from the Shawnees, Senecas, and Delawares came to Bouquet to sue for peace. Bouquet then moved his army from the Tuscarawas River to the Muskingum River at modern-day Coshocton, Ohio. This placed him in the heart of tribal lands and would allow him to quickly strike the natives' villages if they refused to cooperate. As part of the peace treaty, Bouquet demanded the return of all white captives in exchange for a promise not to destroy the Indian villages or seize any of their land. The return of the captives caused much bitterness among the tribesmen, because many of them had been forcibly adopted into Indian families as small children, and living among the Native Americans had been the only life PAGE 12 of 13 they remembered. Some 'white Indians' such as Rhoda Boyd managed to escape back into the native villages; many others were never exchanged. Bouquet was responsible for the return more than 200 white captives to the settlements back east. In 1765, Bouquet was promoted to brigadier general and placed in command of all British forces in the southern colonies. He died in Pensacola, West Florida, on September 2, 1765, probably from yellow fever. REFERENCES "Colonel Henry Bouquet: A Biographical Sketch:" Lieut-General Sir Edward Hutton Warren and Son, 1911, “Broken Promises, Broken Dreams: North America’s Forgotten Conflict at Bushy Run Battlefield” (Article originally from Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine) Anderson, Niles. The Battle of Bushy Run. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1991. Brumwell, Stephen. Redcoats: The British Soldier and War in the Americas, 1755-1763. NY: Cambridge University Press, 2002. Buck, Solon J., and Elizabeth Buck. The Planting of Civilization in Western Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1969. Downes, Randolph C. Council Fires on the Upper Ohio: A Narrative of Indian Affairs in the Upper Ohio Valley Until 1795. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1969. Kent, Donald H. The French Invasion of Western Pennsylvania. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1981. Kent, Donald H., Louis M. Waddell, et al. The Papers of Henry Bouquet. Volumes 1-6. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1976-1994. Nester, William R. "Haughty Conquerors": Amherst and the Great Indian Uprising of 1763. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000.. Parkman, Francis. The Conspiracy of Pontiac. New York: Collier Books, 1966. Peckham, Howard H. Pontiac and the Indian Uprising. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961. Waddell, Louis M., and Bruce D. Bomberger. The French and Indian War in Pennsylvania, 1753-1763: Fortification and Struggle During the War for Empire. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1996. PAGE 13 of 13