Hum 122 - University of Puget Sound

advertisement

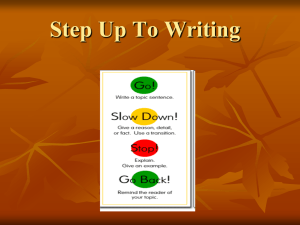

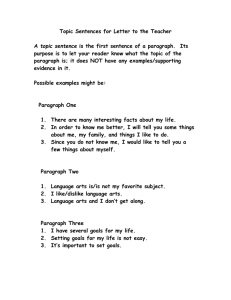

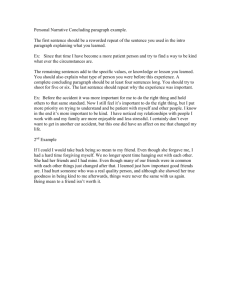

Hum 122 Paper #3: Voltaire’s Candide Spring 2009 Assignment: An essay answering the question, Is Candide a utopian or an anti-utopian book? Due date: Monday, February 16, at the beginning of class. Papers not available at the beginning of class for a classmate to read will be marked down as late. Length: 3 typed double-spaced pages. Purpose: To learn to write persuasive academic argument, in which evidence is marshaled in support of a disputable claim in order to answer a question posed about a text. Writing aim: To become familiar with the basic elements and structure of academic essays. To work on flow and cohesion (“passing the baton” from sentence to sentence). Format, etc.: Give the paper a meaningful title. Otherwise the format is the same as for the first two papers. You may use parenthetical page references instead of footnotes. For this assignment, you’ll take the next step in academic writing by moving from close readings and comparisons to making an argument that answers a larger question about a text. In this case, I’ll provide the question (sometimes called the problem) for you to solve. Your task is to answer the question and support your answer with reasoning about and evidence from Candide. Your answer (often called the thesis or interpretation or argument) will take the form of a disputable claim. By this I mean that your answer to the question—like interesting answers to almost all significant questions—can be challenged and contested by other knowledgeable readers of Candide. Because the question I have posed can be answered either way, you’ll not prove your point simply by asserting it again and again. You’ll need to figure out a strategy for convincing skeptical readers that your claim is plausible. Making your case will require you to think about how to set up and unfold your argument. It will also require you to develop evidence for the claim by using the techniques of close reading that you have already learned. You might also find the techniques of comparative analysis helpful because deciding if Candide is a utopian book might depend on the understanding of utopianism gained from reading The Republic and Utopia. The “preps” for the classes on Candide pose questions that can help you decide on your thesis. Preparatory reading for this paper: For excellent advice about this kind of paper, read Gordon Harvey’s “Elements of the Academic Essay” (attached to this assignment sheet) and the Harvard Writing Center’s online handouts entitled “Overview of the Academic Essay,” “Essay Structure,” and “Counter-Argument.” In writing this paper I want you to work on cohesion (the flow in a paper from sentence to sentence and from paragraph to paragraph). One way to improve cohesion is by keeping the topics and the point of view consistent throughout a paragraph. You can test for consistency by underlining the grammatical subject of every clause in a paragraph. If the paragraph is cohesive, the words that you have underlined should seem to be a related set of topics. They do not have to be identical but they should be closely associated with one another. Remember what we learned about characters and actions, and you’ll realize that you can make a paragraph seem focused and cohesive by presenting it from the point of view of one person (e.g., Candide, or Voltaire, or a reader of the book Candide.) Another way to improve cohesion is to provide clear transitions that guide readers through the unfolding logic of your argument. Think of the sentences in a paragraph (and the paragraphs in 1 the whole paper) as runners in a relay race. At the end of each leg of the relay, the runner must pass the baton to the next runner, who begins another leg. Less metaphorically, what this means is that each sentence (or paragraph) should end with the word, topic, issue or concept that the next sentence (or paragraph) will take up. In effect, the baton should be extended for the next runner to grab. Correspondingly, at the front end of the sentence you place the ideas and concepts that you have already referred to. In effect, you should begin a sentence by grabbing the baton. Thus, you move the old and familiar to the front of the sentence and place the new and significant at the end. Put another way, you end each sentence with the new thing that you intend to emphasize. Here are two examples. The first set of sentences lacks cohesion and so the discussion seems disjointed. In the second set, the sentences flow into one another; as a result, the discussion seems focused. The examples come from Wayne C. Booth, Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams, The Craft of Research (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1995), 225-26. The biosphere could be permanently damaged if rain forests continue to be stripped to serve these short-term interests. National policies that deal with local problems and ignore the global impact will not halt this damage. Only the efforts of the industrialized countries of the world will achieve that goal. If rain forests continue to be stripped to serve these short-term interests, the biosphere could be permanently damaged. This damage will not be halted by national policies that deal with local problems and ignore the global impact. That goal will be achieved only by the efforts of the industrialized countries of the world. Here is another set of examples. In the second, improved version, note that the writer violates the advice about characters and actions in order to accomplish a more important purpose—improving the flow between the sentences by passing the baton: Because the naming power of words was distrusted by Locke, he repeated himself often. Seventeenth-century theories of language, especially Wilkins’ scheme for a universal language involving the creation of countless symbols for countless meanings, had centered on this naming power. A new era in the study of language that focused on the ambiguous relationship between sense and reference begins with Locke’s distrust. Locke often repeated himself because he distrusted the naming power of words. This naming power had been central to seventeenth-century theories of language, especially Wilkins’ scheme for a universal language involving the creation of countless symbols for countless meanings. Locke’s distrust begins a new era in the study of language, one that focused on the ambiguous relationship between sense and reference. In both of the improved examples, notice how the writer places familiar information at the start and unfamiliar information at the end of sentences. In short, the writer is passing the baton! IMPORTANT REMINDER: You must use the services of the Center for Writing and Learning for at least one paper in this course. (See page four of the syllabus for details.) This assignment is the first of three opportunities to do so. Because this paper is more complicated than the first two, it can benefit from the scrutiny and suggestions of one of the Center’s excellent writing advisors. 2